Scientific Illustration

Art in service of knowledge

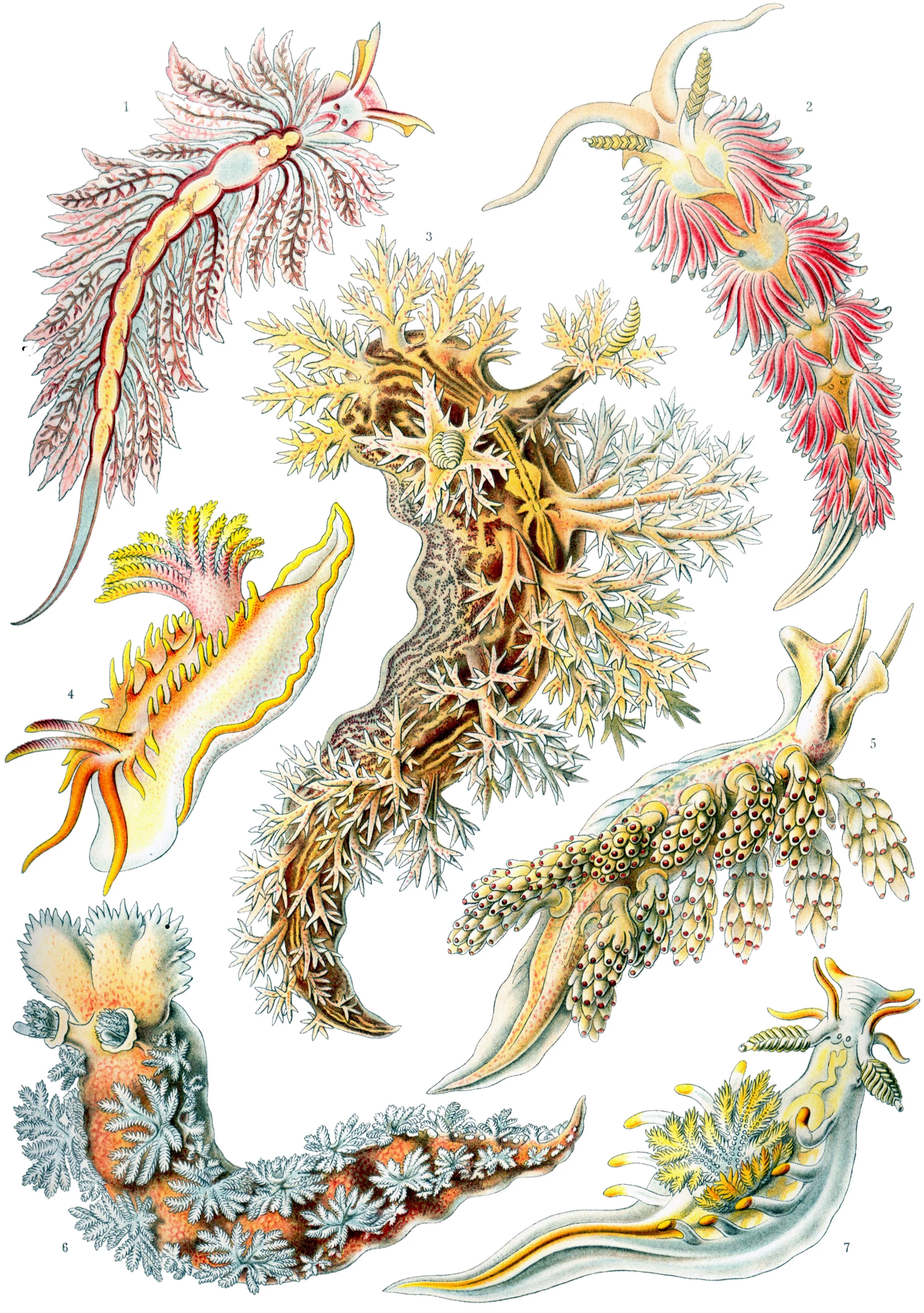

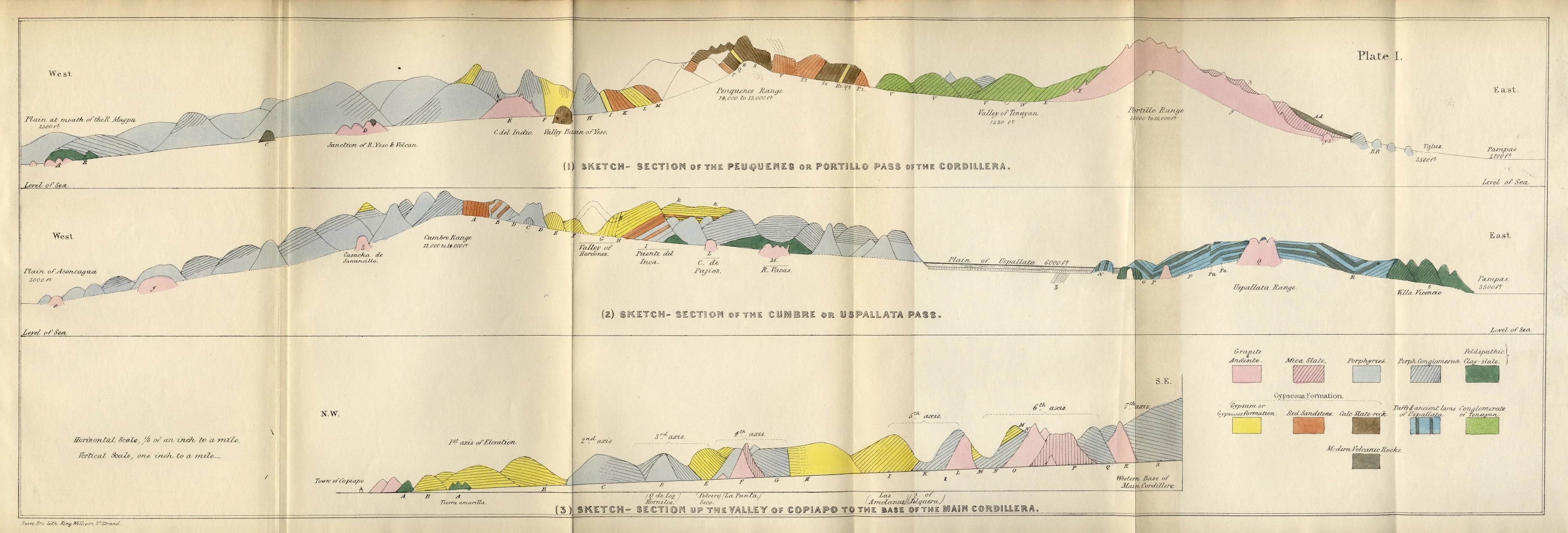

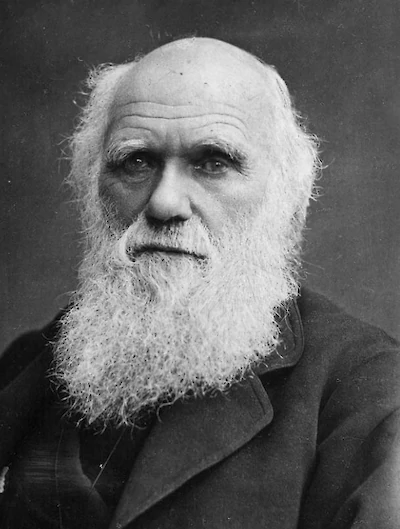

On a blustery fall night in 1836, Charles Darwin arrived in the port city of Falmouth, stepping onto English soil for the first time in four years. Darwin’s travels on the H.M.S. Beagle had taken him to South America, the Galápagos Islands and Australia, where he had collected thousands of specimens of fossils, birds, fish and reptiles. But back in England, his work had just begun. Before Darwin could share his discoveries with the scientific world, someone had to draw them.

Before the camera came along and made image-making easy, scientists who wanted to share their work visually had to collaborate with specialized scientific illustrators. According to the Franklin Institute, scientific illustration is “a way to communicate complex concepts, details, and subjects in an engaging and easily comprehensible way” or more simply, “art in the service of science.” Scientific illustration is a technical art, requiring accuracy, clarity and precision.

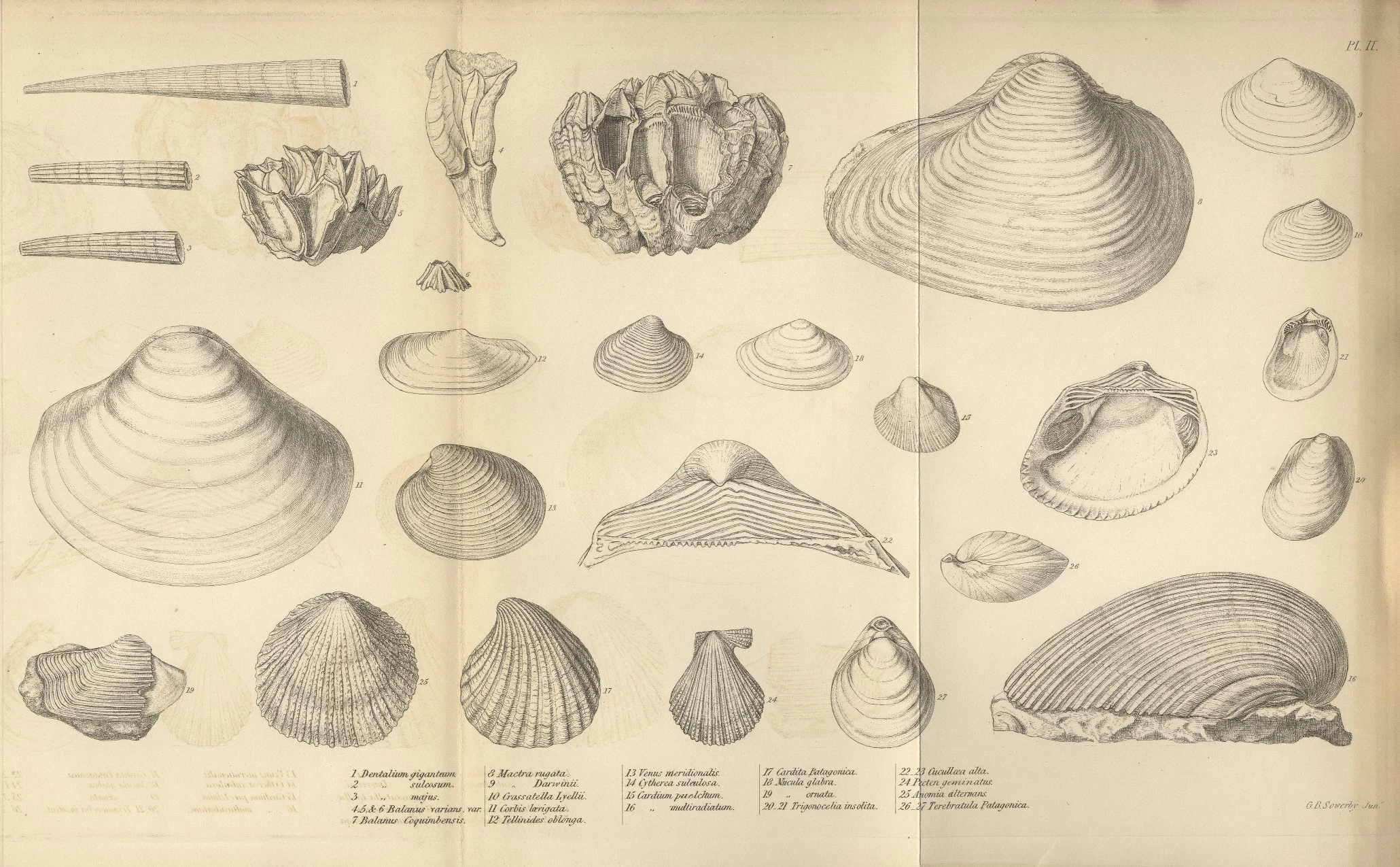

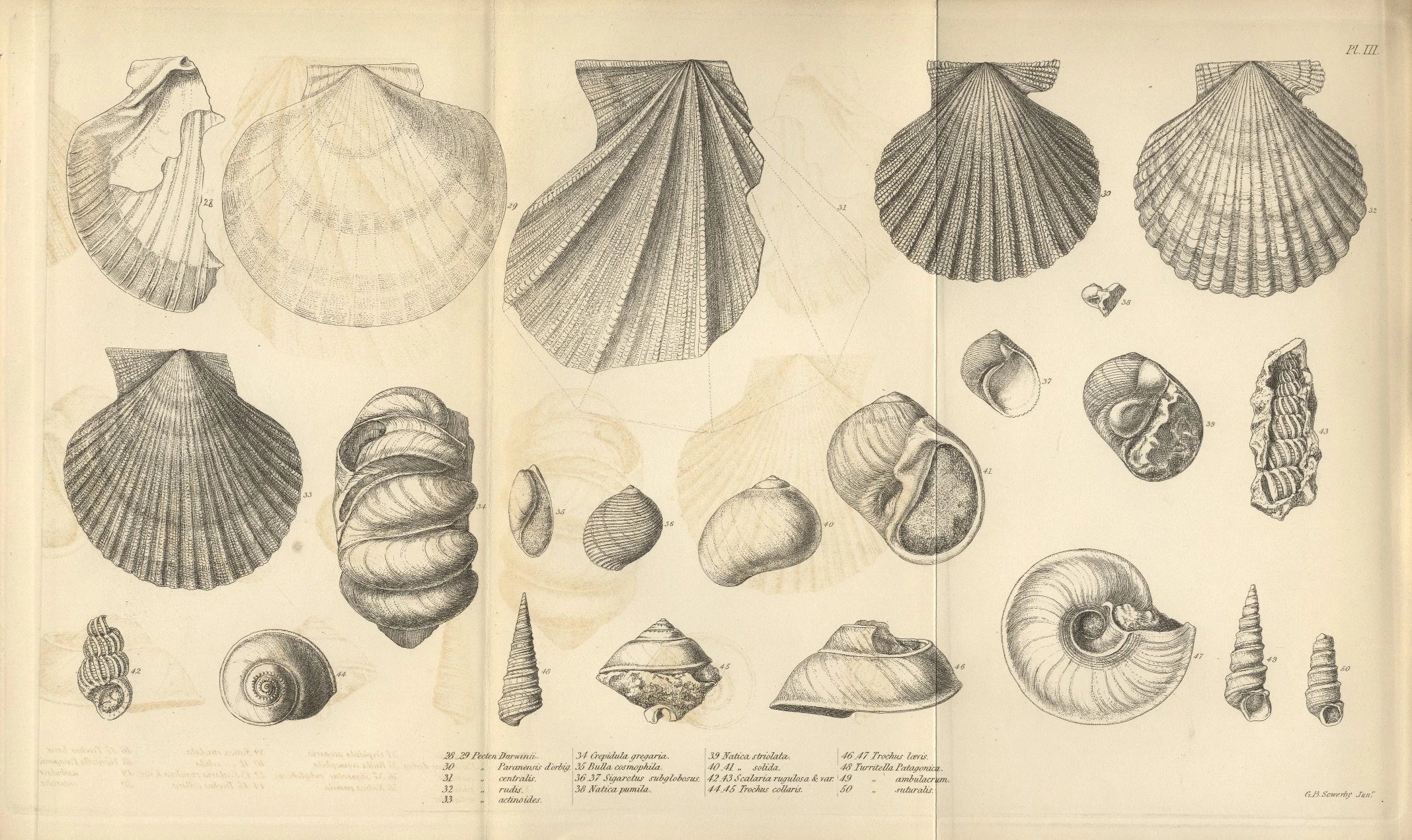

For his fossil specimens, Darwin commissioned the respected German draftsman and lithographer George Johann Scharf, whose delicate renderings of toxodon skulls and Macrauchenian vertebrae launched the 27 year old Darwin to international fame. Though Darwin eventually fired Scharf because he couldn't afford the artist’s services, this yin-yang of research with artistic illustration has always been essential to the development and sharing of scientific knowledge.

Western science, as it emerged from Ancient Greek and Roman physicians like Hippocrates and Galen, defaulted to the written word to document itself—notes on dissections and surgeries intended to be shared with other surgeons. It wasn't until the 13th century when the Islamic physician Ibn al-Nafis used illustrations to dispute Galen’s written theories. Even then, in the years before the printing press, these illustrations were hand-crafted and lost accuracy with each scribe’s transcription. For the next few centuries, science remained largely a live performance, conducted in the surgery and classroom.

Leonardo da Vinci developed a fascination with anatomy after attending dissections of executed criminals, and turned his chalk and pencil to the scientific diagramming of the human form. The realistic depiction of the body became a grail among Italian Renaissance artists, Da Vinci joined art with science, and evolved the flat schematics of Ibn al-Nafis into richly shaded tissues and strident musculature.

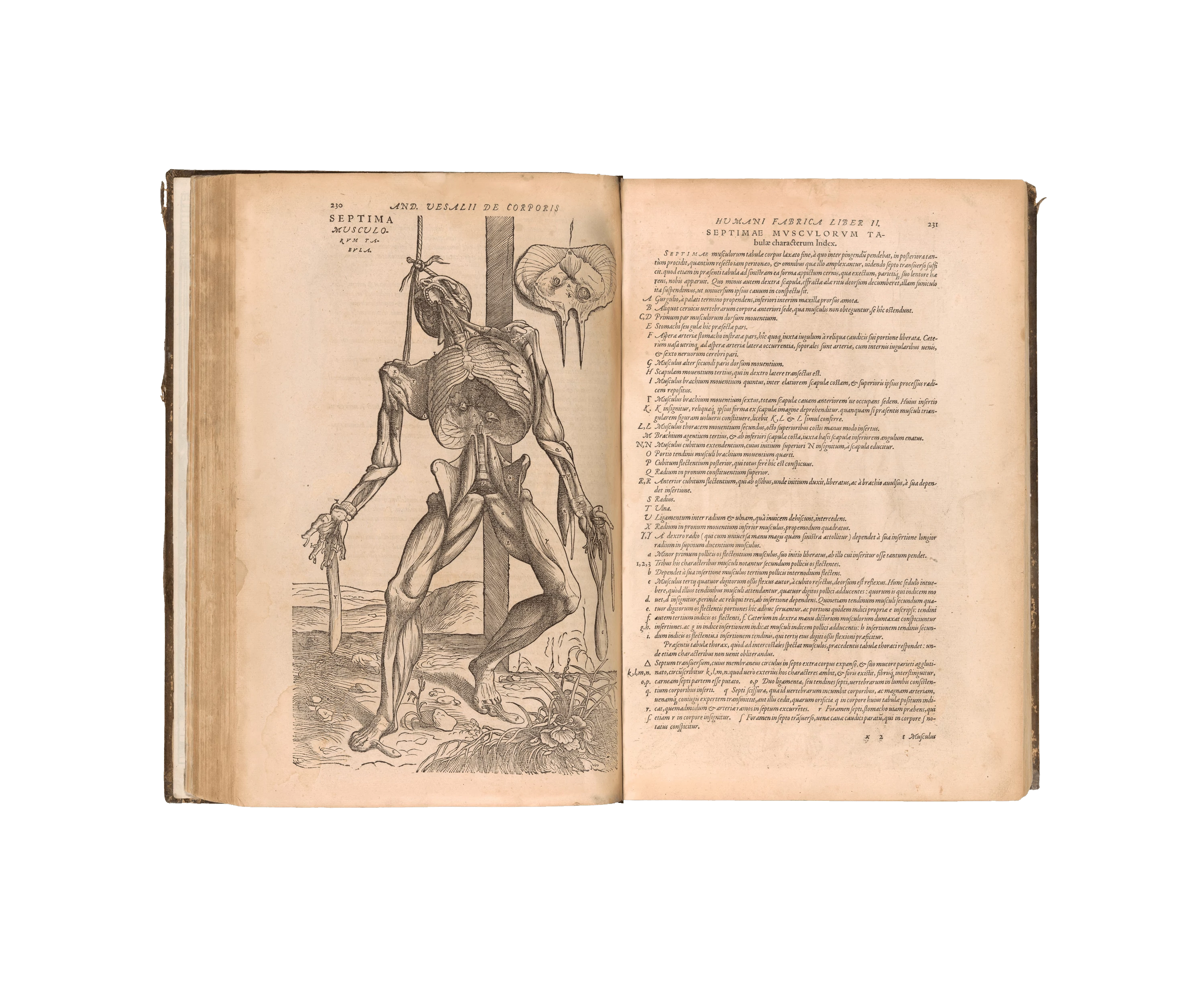

The renaissance sparked a fire for naturalism that was carried on by both scientists like the Belgian anatomist Andreas Vesalius and by artists like Albrect Durer. Vesalius took advantage of engraving and printing press technologies to publish De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) in 1543. Vesalius’s illustrations were both medically accurate and artistically expressive, showing his flayed figures posed contrapposto against an aerial view of a northern Italian landscape. Durer explored the world of natural history, engraving wildlife and the extraordinarily detailed series Eight Studies of Wild Flowers.

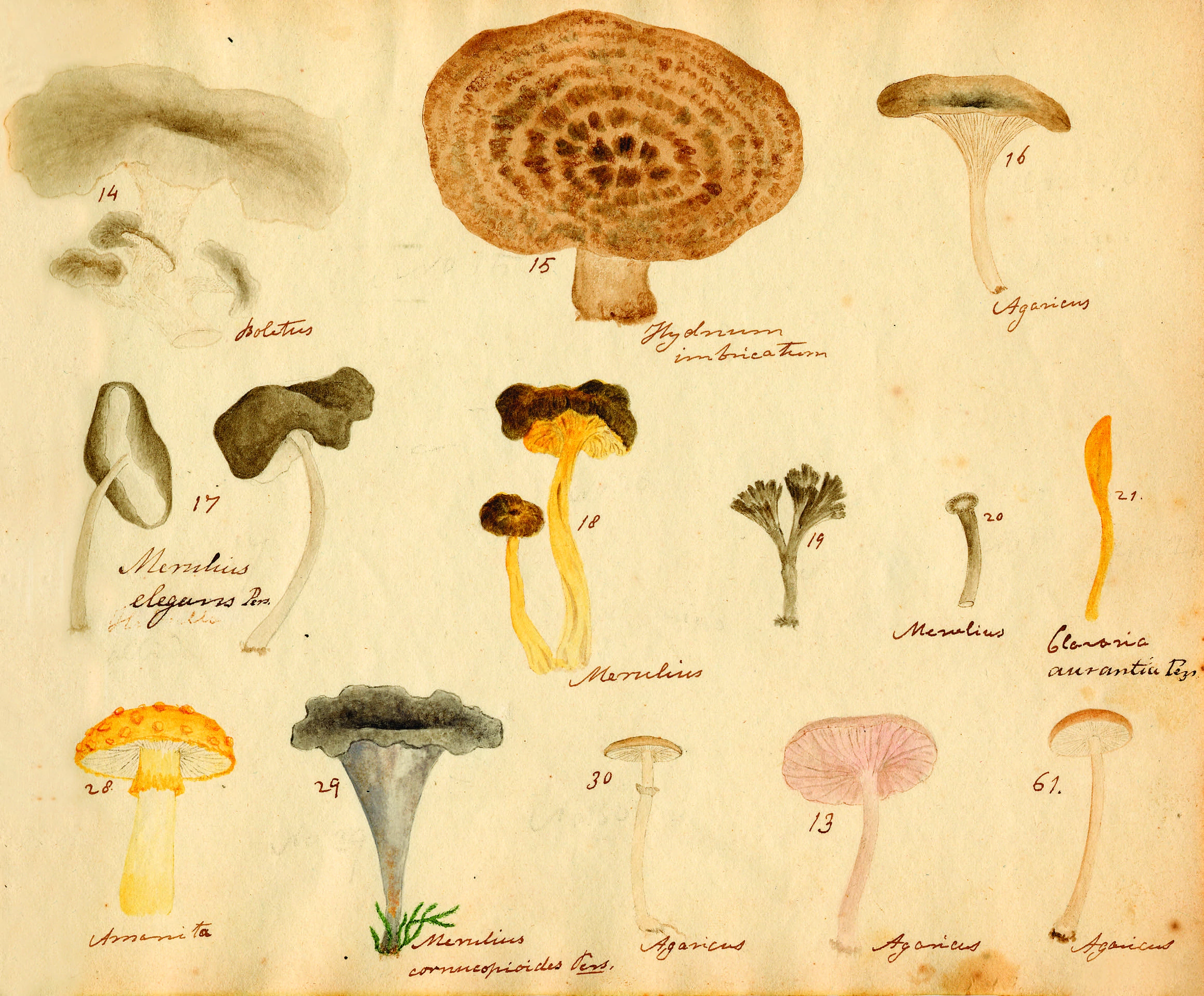

The pursuit of knowledge became an obsession in the 16th and 17th centuries, and scientific illustration evolved into a surprisingly egalitarian pastime. Amateur naturalists collected specimens of animal skeletons and fungi for their cabinets of curiosities. The invention of the microscope in the 1590s brought the interior vistas of cellular structure into view, and in 1665 Robert Hooke published Micrographia, pairing scientific diagrams with captions aimed at a wide general audience.

Science is often belived to be something best left to professionals, but the Age of Enlightenment (1650-1701) blew this paradigm wide open. Academic societies had long held the keys to scientific publication, but wider distribution of printed materials allowed curious individuals to take the discovery and documentation of the natural world into their hands. And though scientific societies were notoriously exclusionary boys-clubs, many women became self-taught naturalists.

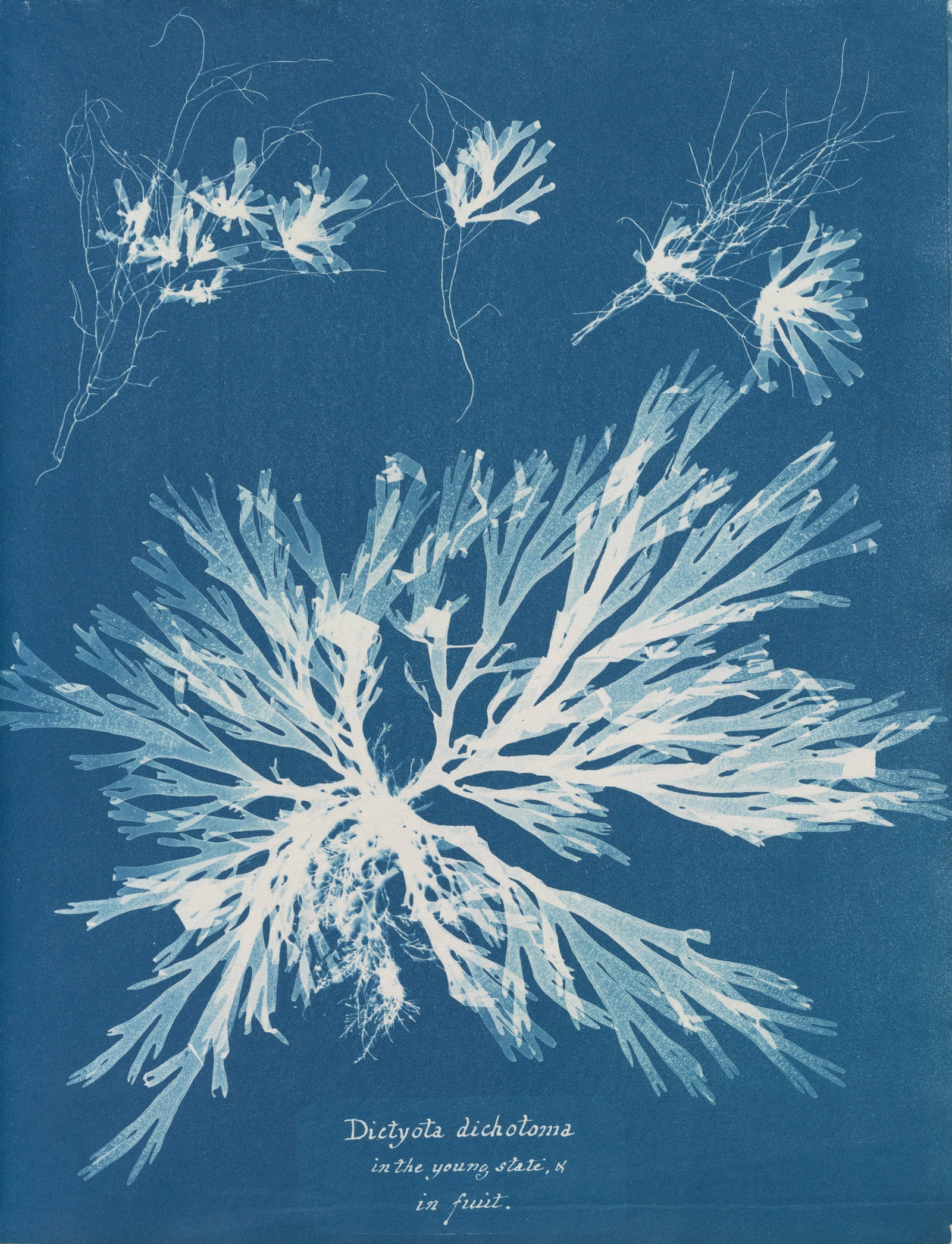

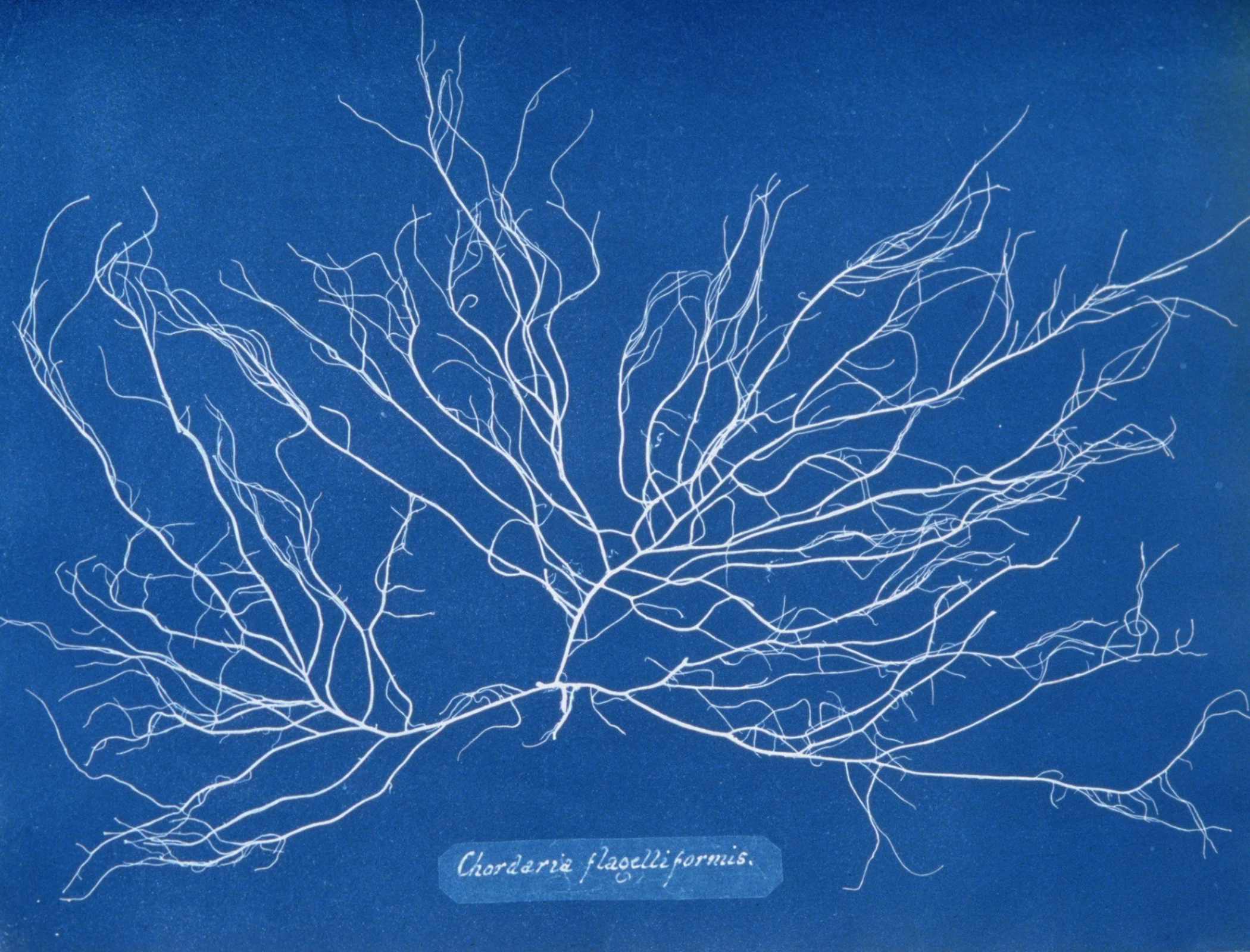

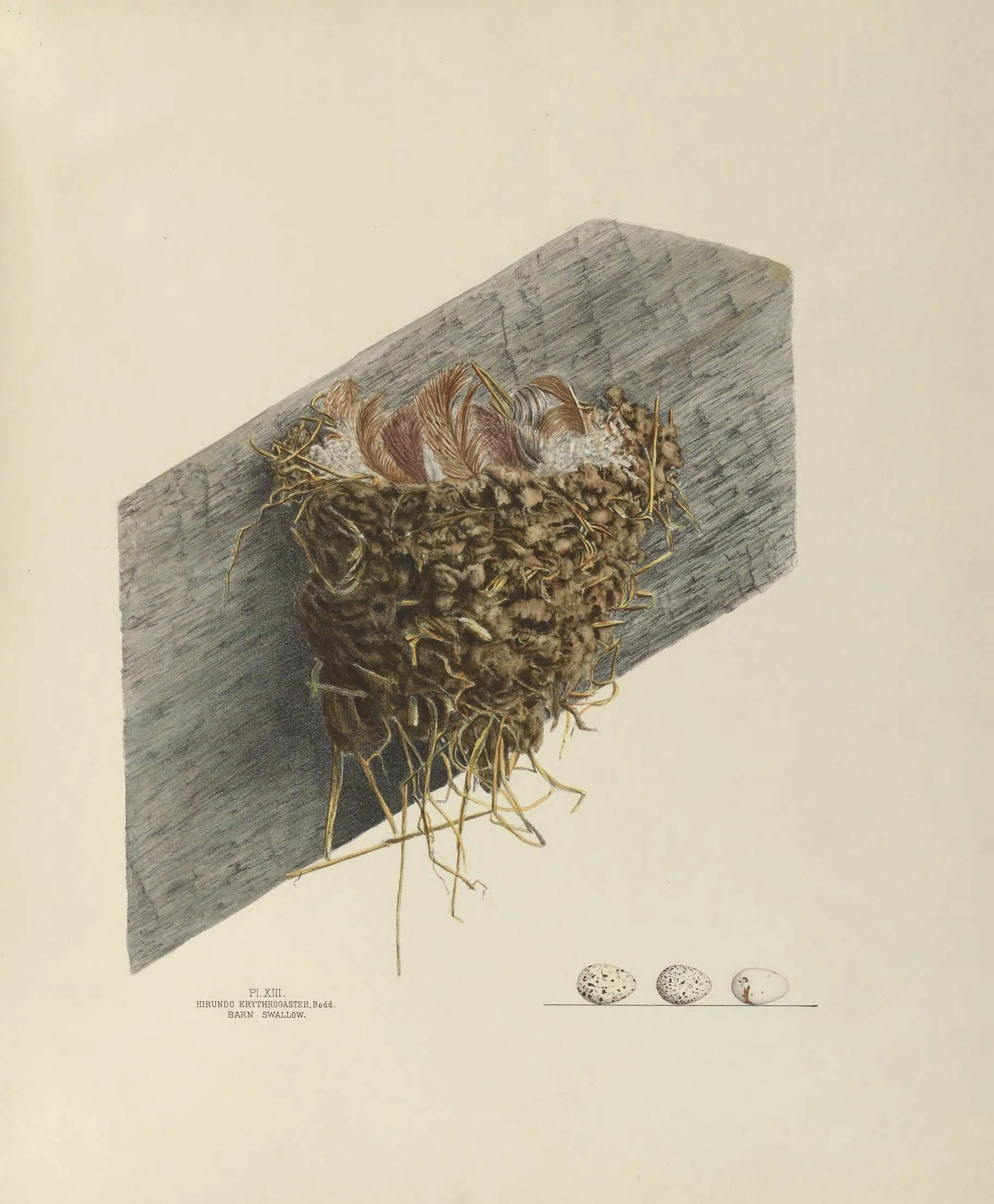

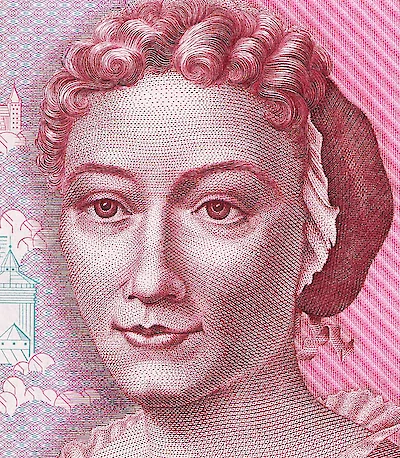

Becoming both field researchers and illustrators, artists like Anna Atkins, Sarah Stone, Genevieve Jones, Beatrix Potter and Orra White Hitchcock exhaustively documented thousands of species of algae, mushrooms, and the eggs and nests of birds in watercolor, drawings, and lithographs. Each woman fought the battle for recognition. Beatrix Potter engaged her father to present her paper of fungal spores to a mens-only mycology society. Genevieve Jones self-published her book on birds nests and eggs, a project carried on by her devoted family after her early death. Anna Atkins learned from the inventor of the cyanotype, and applied this revolutionary process to create the first book illustrated with photographic images—a ten year project resulting in the masterwork Photographs of British Algae. It’s a testament to these women that despite nigh-impenetrable institutions, their work is referenced to this day for its precision, elegance, and scientific value.

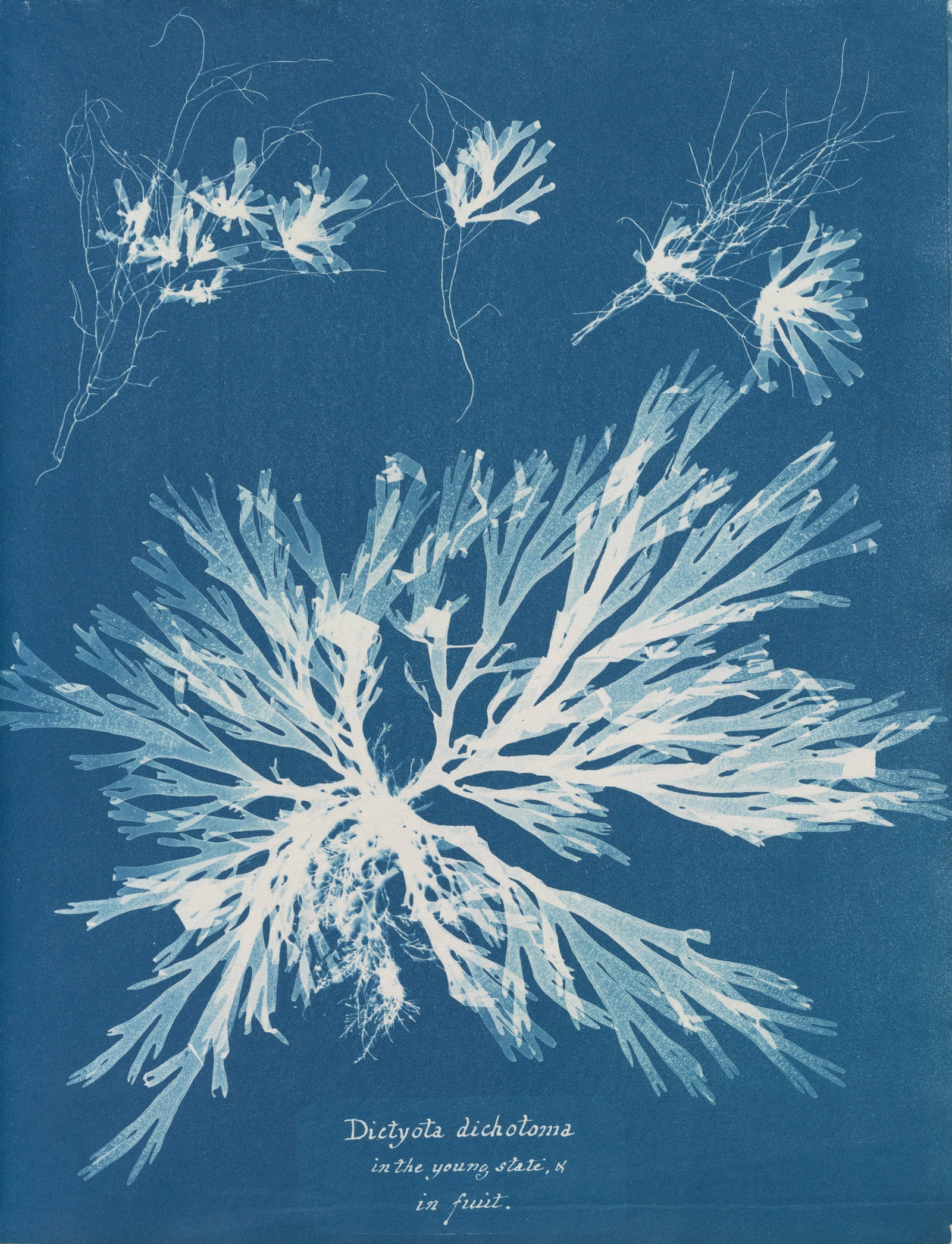

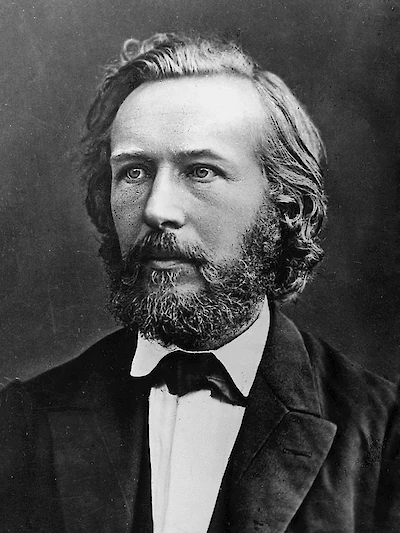

Sweeping statements are always fraught, but its fair to say that the tone for modern scientific illustration was set in the late 1800s by Ernst Haeckel, an ambitious young zoologist who saw Darwin’s Origin of Species and embarked on a frenzied attempt to out-do the elder generation of naturalists. For his second major volume, Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte, Haeckel pulled out all the stops, blending numerous specimens into florid tapestries of leaves, spines and tentacles. His images are mesmeric and unsettling, a shocking window into the weirdness of nature, and the bright colors and dramatic juxtapositions catapulted him into international popularity. Today, scientific illustration is largely carried out via 3D renders, interactive infographics and videos, but Haeckel’s flair for the dramatic is visible in Nasa’s false-color nebulas and the dense layers of a National Geographic diagram.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Scientific Illustration? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

Electric blue: the first photographic book

1799 – 1871

The art of seeing

1809 – 1882

The beautiful weirdness of nature

1834 – 1919

Even death will not stop us

1847 – 1879

Friend of the birds

1785 – 1851

A botanist gets a divorce and travels the world

1647 – 1717

Of Love and Mushrooms

1796 – 1863