Femme Fatales

The rise, fall, and rebirth of an archetype

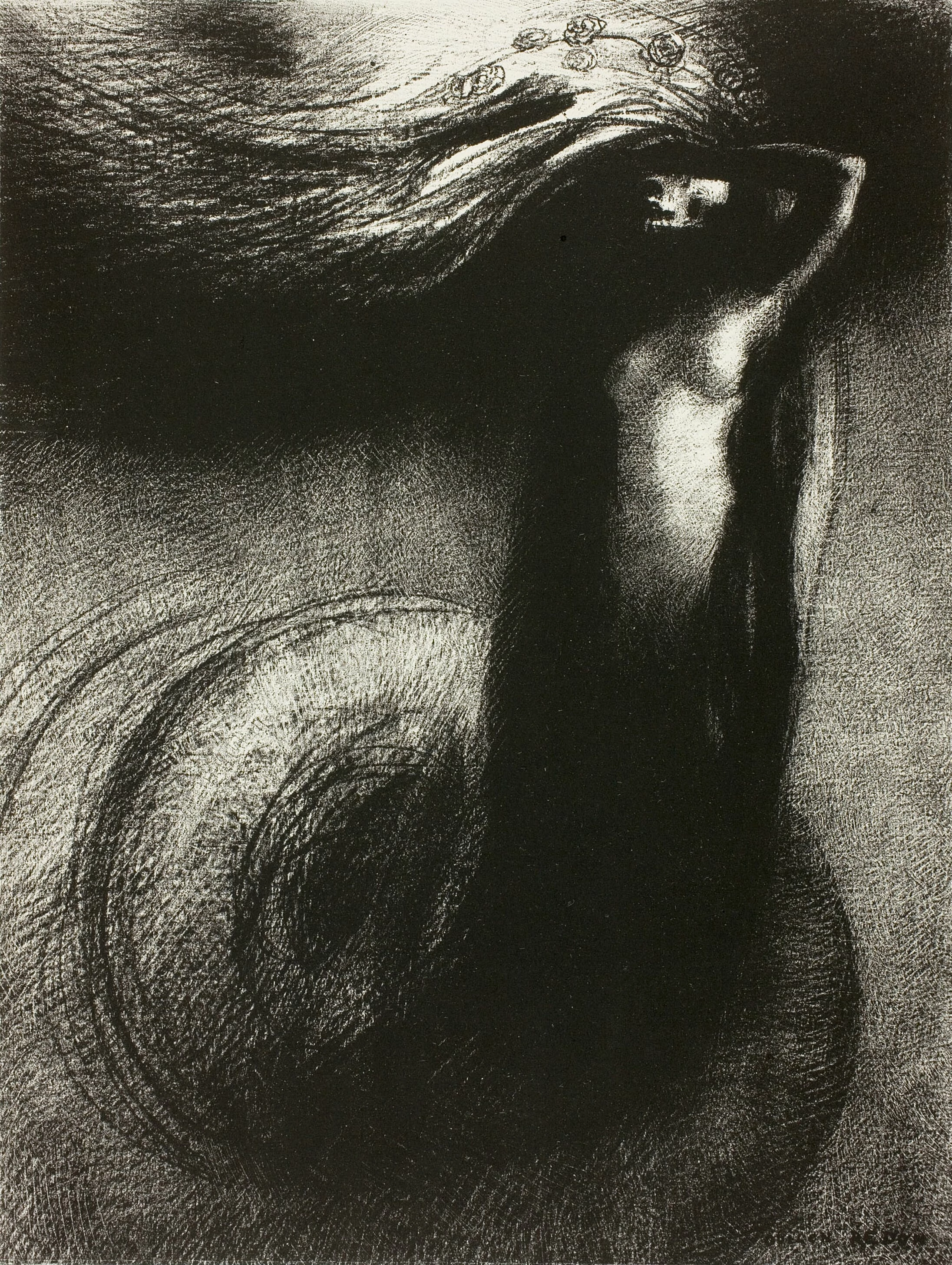

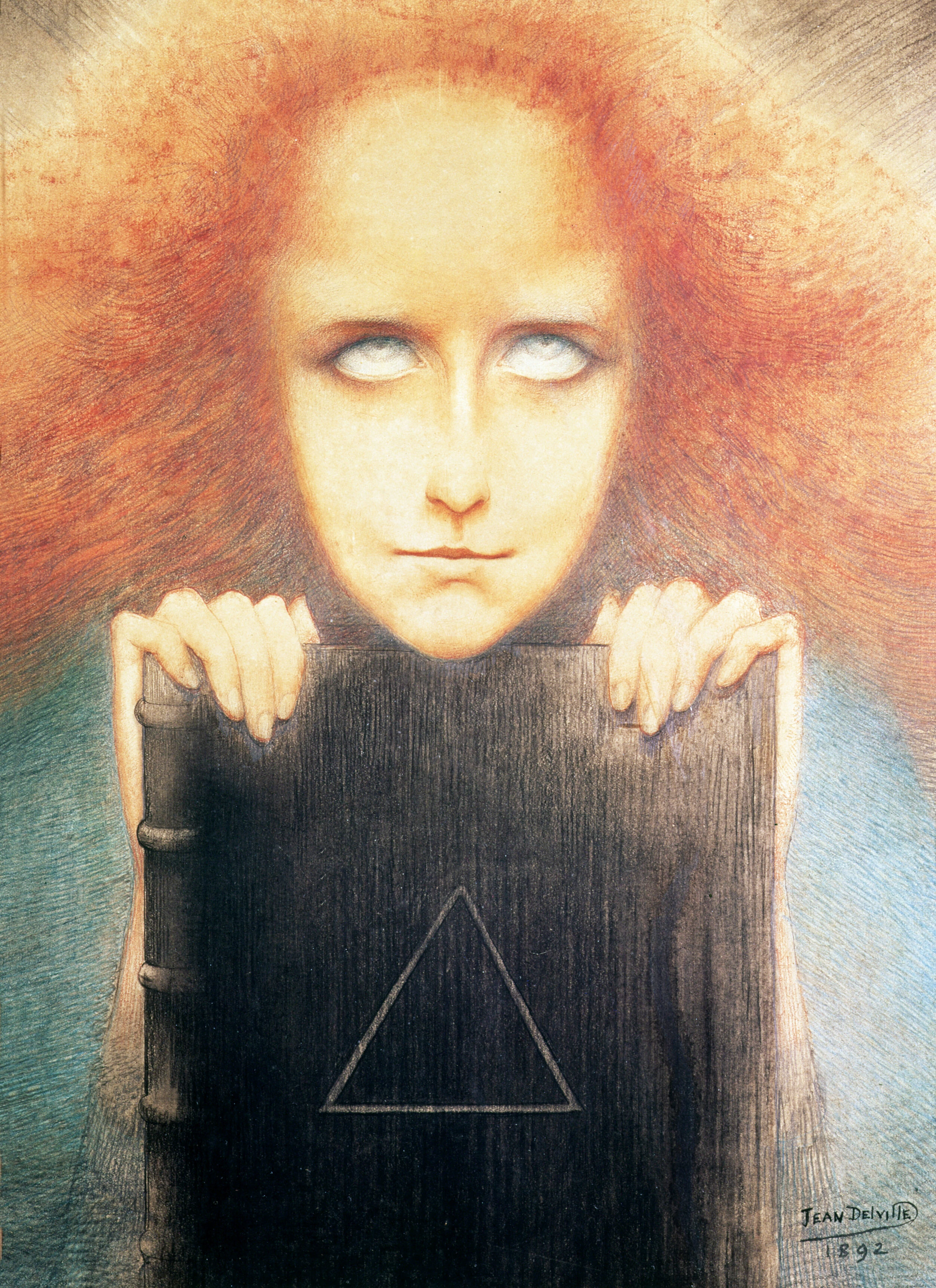

Suddenly, she was everywhere. As the end of the nineteenth century neared, the archetype of the femme fatale silently took over the conservative wing of the art world. While the Impressionists captured dappled light over haystacks and the Realists illustrated the mundane labor of the working class, the Pre Raphaelites, Symbolists, and even some Academic artists of the Paris salons fell under the spell of the deadly woman.

The femme fatale is an old archetype, appearing in cultures around the world. In Ancient China, she was personified by the infamous consort Daji, whose beauty hypnotized the last king of the Shang dynasty into carrying out sadistic atrocities on his subjects, driving the kingdom into ruin. In Hindu mythology, a class of female assassins called Visha Kanya seduced their victims and poisoned them with their own bodily fluids. The Ancient Greek poet Homer retold the legend of Circe in The Odyssey, “a dreadful goddess with lovely hair and human speech” who lured men to her island palace and turned them into animals when she tired of them.

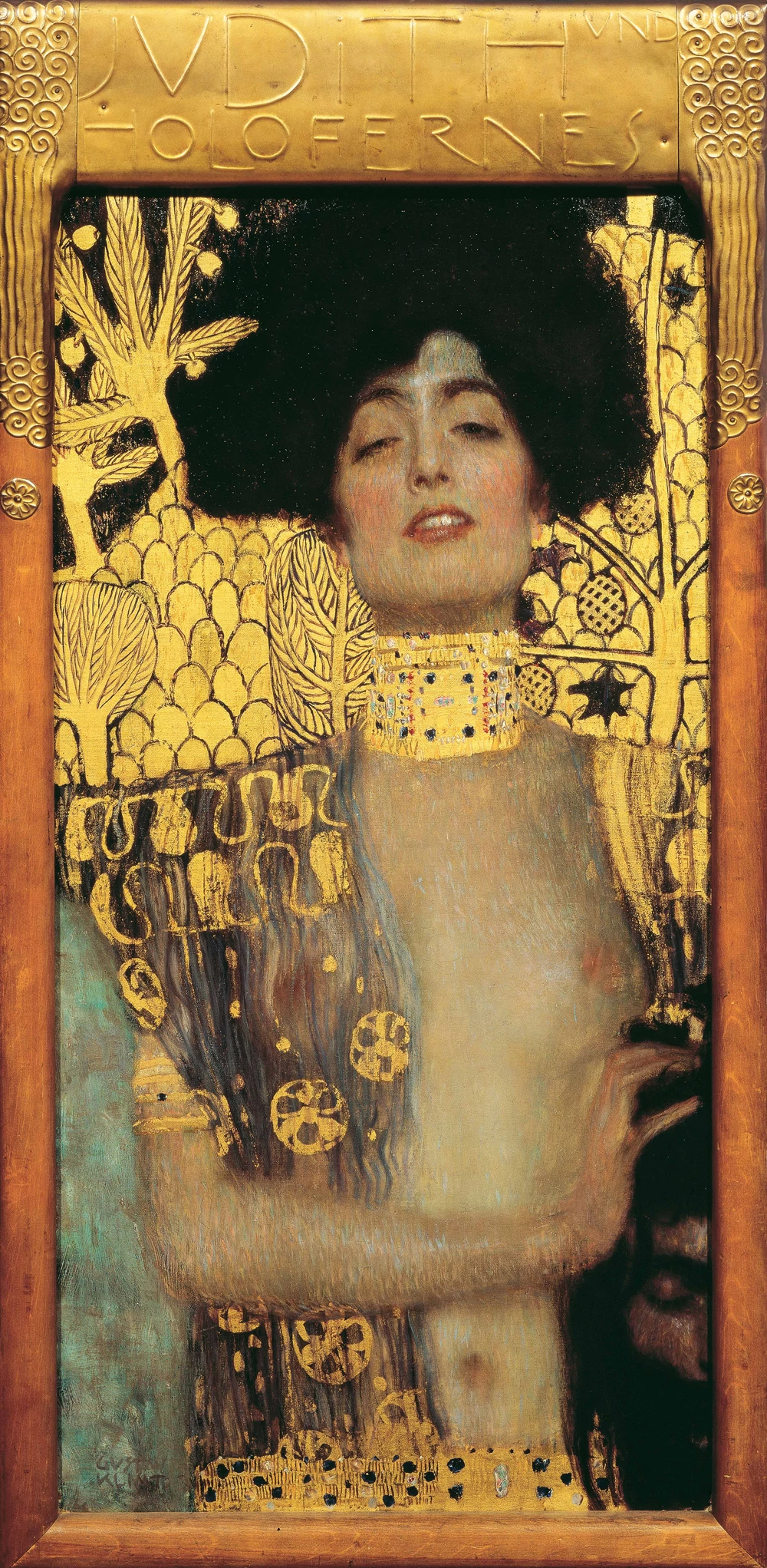

In western cultures, many of the femme fatales that haunt the public consciousness come from the Hebrew Bible, which is full of stories where seductive women destroy men. Delilah shaved Samson’s long hair to strip him of his superhuman strength. The Phoenician princess Jezebel married King Ahab of Israel and promptly installed a new religion, sparking violence and bringing ‘divine punishment’ upon the kingdom. And we can't forget the beautiful Salome, whose dancing so pleased King Herod that he promised her anything she wanted, up to half his kingdom, and she asked for a man’s head on a platter.

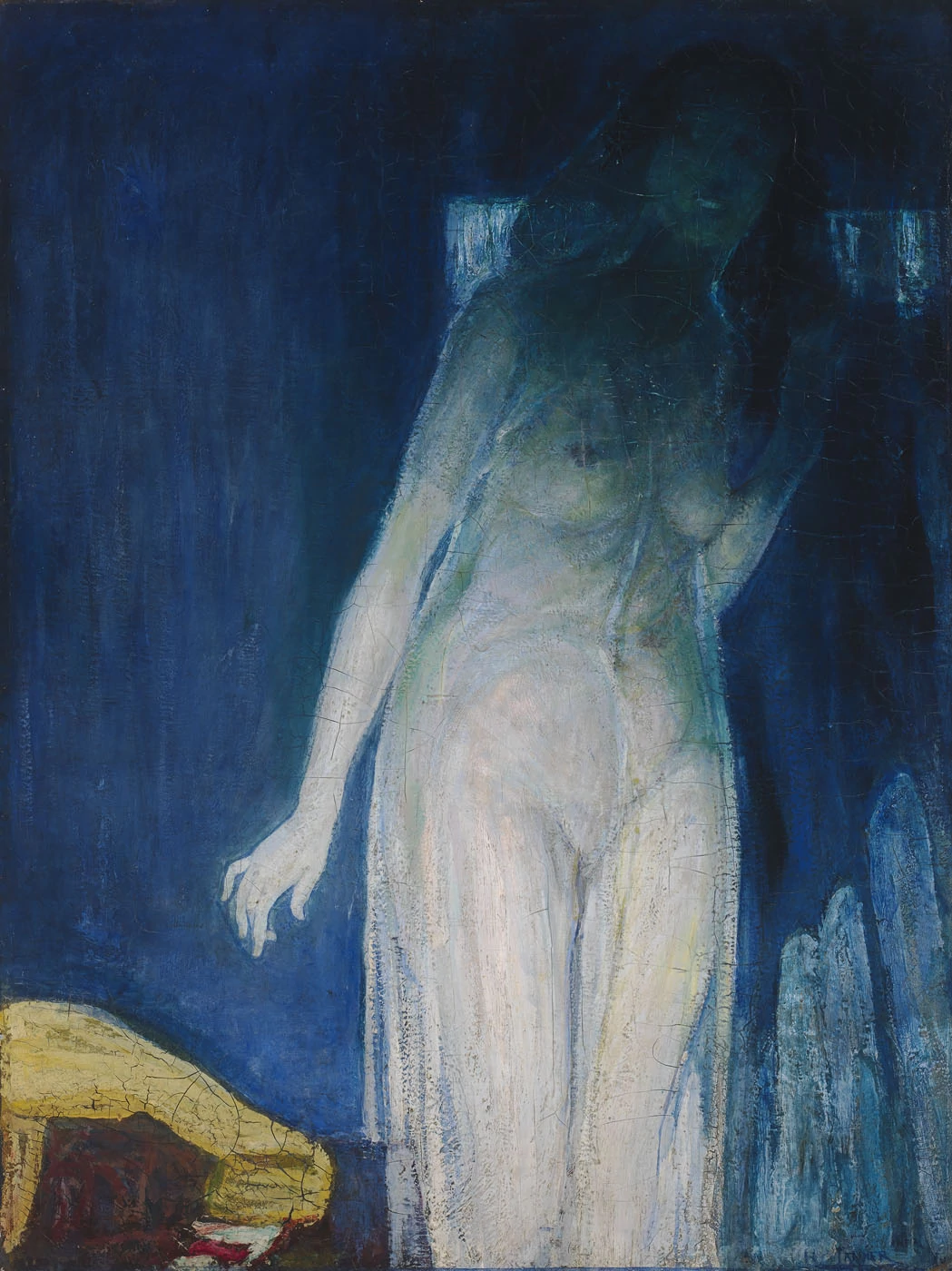

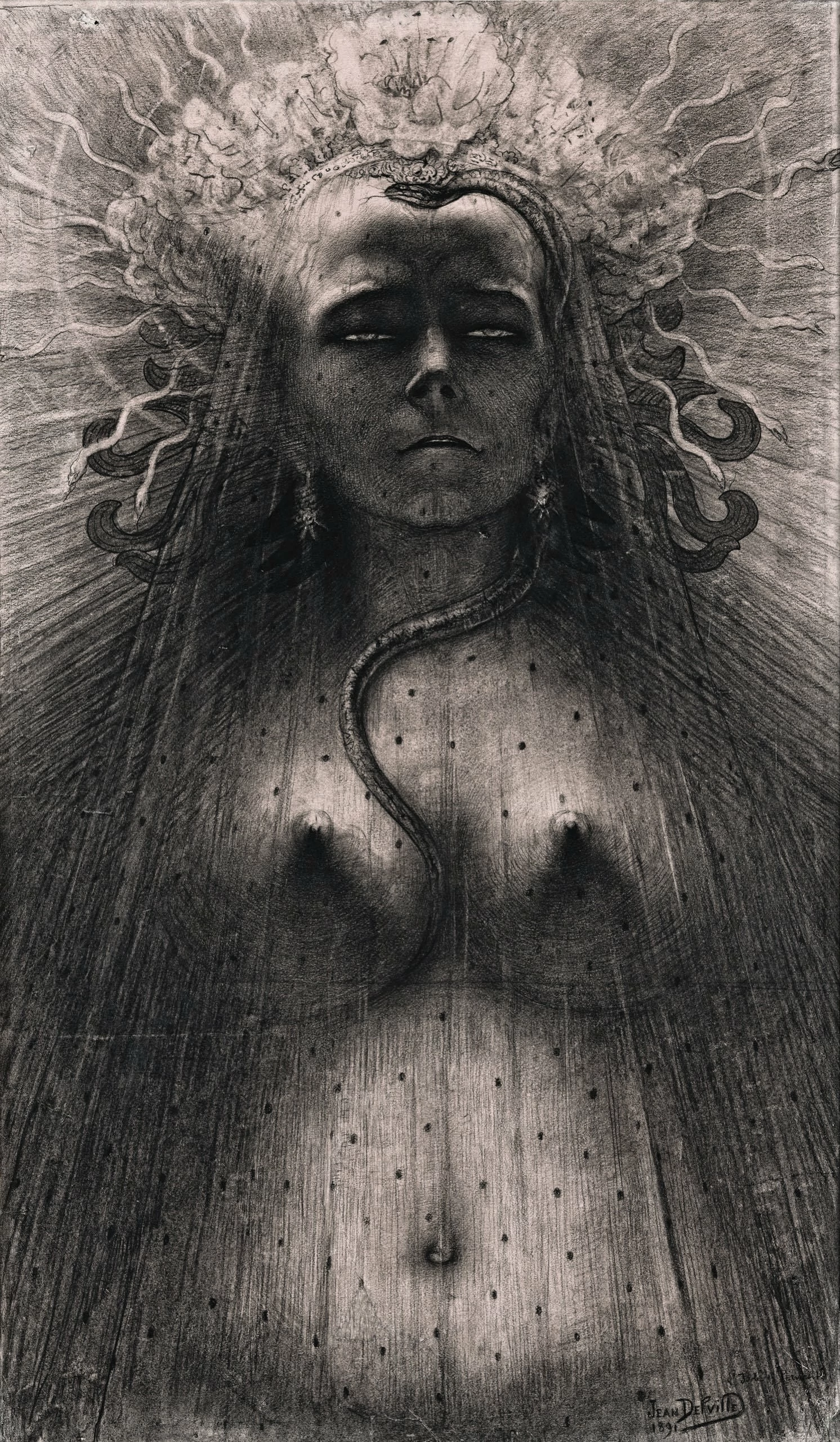

While the Femme Fatale appears all over history, she was one archetype among many—often relegated to a wayward chapter or cautionary tale, rarely the star of the show. But in the late 19th century, she flourished like never before. The Madonna became threatenly alluring, Lilith became the muse of choice, and death itself was personified as a woman. So why the sudden popularity of deadly women in fin de siècle [French for end of century] art? As with any artistic theme, it’s a tangled web, but we’ll look a few reasons why the femme fatale took over, and what it all means to art viewers today.

The most influential vanguard of the deadly woman archetype was probably the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Seven naive and idealistic young men founded the movement in 1848, aiming to rewind art to before the ‘corrupting’ influence of Renaissance humanism, back to the stiff, formal, saccharine moralizing of medieval quattrocento artwork. The Pre-Raphaelites were an oddity of their time—a deeply conservative, even regressive movement. But they were undeniably influential, in part for their central obsession, the tension between strict Victorian morals interpreted through an arthurian lens of knights and chivalry, and the pathetically earnest quest for romance and stifled desire for sex.

The Pre-Raphaelites were obsessed with women and had no idea how to relate to them. In their artwork, women were crystalline ivory goddesses, delicate, perfect, as distant and unknowable as space aliens. The ringleader of the crew was Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose worship ricocheted from his mistress Fanny Cornforth, painted as Lady Lilith in 1868, to Alice Wilding, whose face Rosetti painted on top of Fanny’s Lilith four years later, to Jane Morris, who modeled for Rossetti’s Proserpine a few years after that. Rosetti set the tone for the Pre-Raphaelite depiction of women. While not actively malevolent like the coming generations of femme fatale, these inscrutable beauties were deadly for the self-destructive adoration they inspired.

It’s no accident that the Femme Fatale exploded in popularity at the same time as a new archetype was born. The roles of women in society were changing rapidly in the second half of the 19th century. The populist revolutions of 1848 had sowed seeds of liberalism across Europe, the growth of women’s suffrage movements through the 1860s called for women’s inclusion in newly democratic political arenas, and industrialization provided hard-won access to education and employment near the end of the century. These and many other factors had lit a path to independence and security outside of the patriarchal constraints of marriage and motherhood. Enter the New Woman.

The New Woman was intellectual, independent, and sexually autonomous. She rode bikes, smoked cigarettes, and didn't need no man. Like many archetypes, the New Woman was part real, embodied by social reformers, writers, poets, and artists like Berthe Morisot, Alice Austin, and Romaine Brooks, and part invention, a larger-than-life caricature used as an ideal by those who supported women’s emancipation, and as a object of concern, scorn, or ridicule from the conservative voices in society.

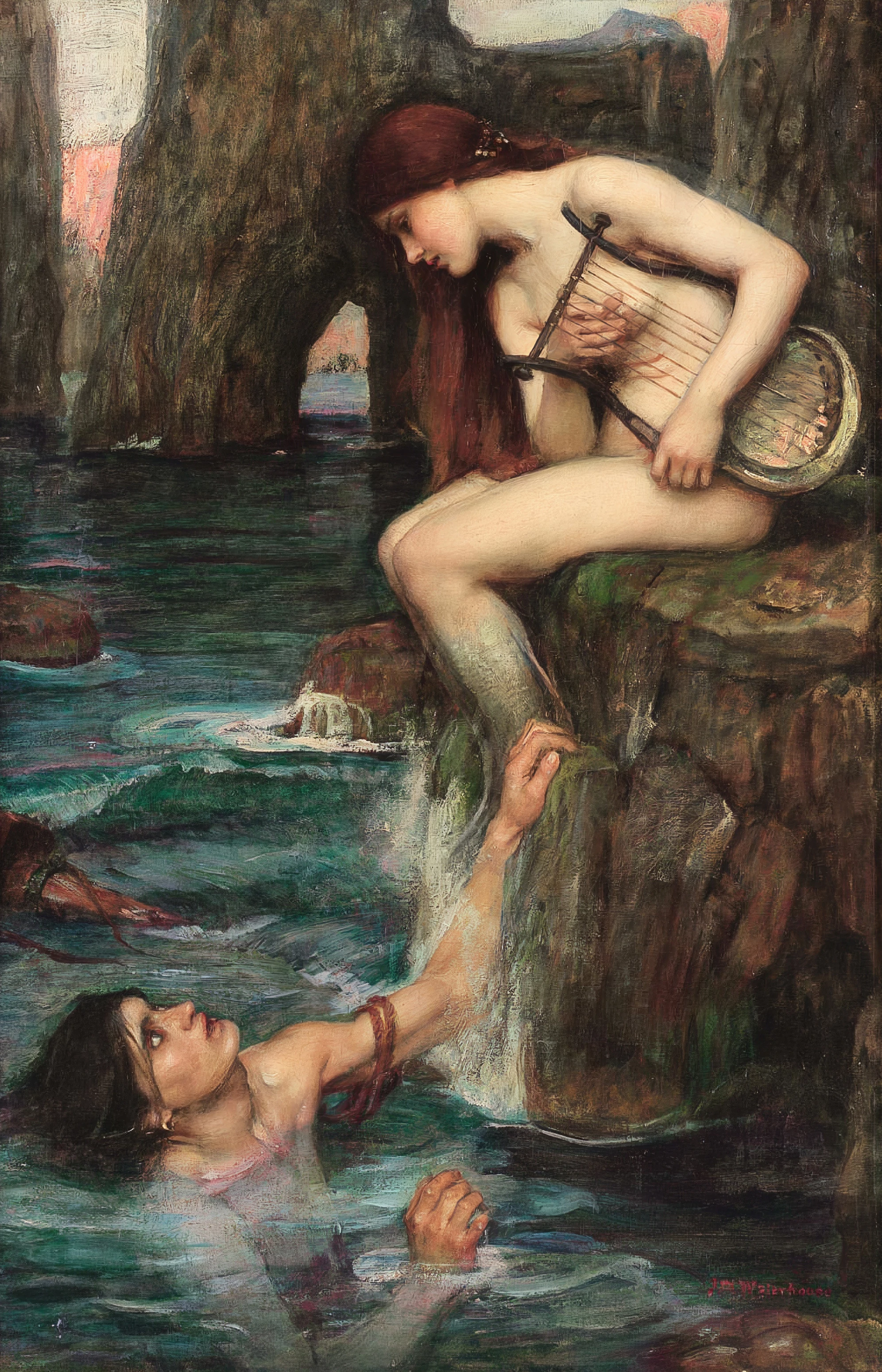

The femme fatale mirrors the anxiety of a patriarchal society that fears what it can't control. If women can leave the house, wear pants and educate themselves, what might they do next? Poison their long-time oppressors? I suspect this paranoia contributed, at least in part, to the less sexy side of femme fatale depictions—where women are monstrous, often part beast, intent on devouring men. In this camp we have Gustave Moreau’s plaintive Sphinx, and the bird-bodied sirens by John William Waterhouse.

Much of the European art world in the 19th century embraced “La Vie Boheme” or the bohemian life, a sort of indulgent self-exile from mainstream culture, where intellectual curiosity and creativity earned you the right to divest yourself of bourgeois morality. For many artists that meant visiting a lot of prostitutes and visiting prostitutes led to syphilis. At the time there was no treatment for the disease, and infection meant living with painful side effects and eventual death. It’s believed that Manet, Gauguin, Van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec all suffered from various forms of syphilis, alongside other venereal diseases like gonorrhea.

Sex workers were blamed for the epidemic. Prostitution became known as ‘The Great Social Evil’ and in the UK, the Contagious Diseases Acts of 1864 allowed police to detain suspected prostitutes for compulsory medical checks. Women who were determined to be infected were detained at the notorious ‘lock hospitals’ until recovery or the end of a criminal sentence. There were no checks or detainments for men, and the social and moral panic around prostitution only strengthened the ties between sex and death in art. Sex was dangerous, and the archetype of the femme fatale made sure the woman was the scapegoat.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Femme Fatales? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.