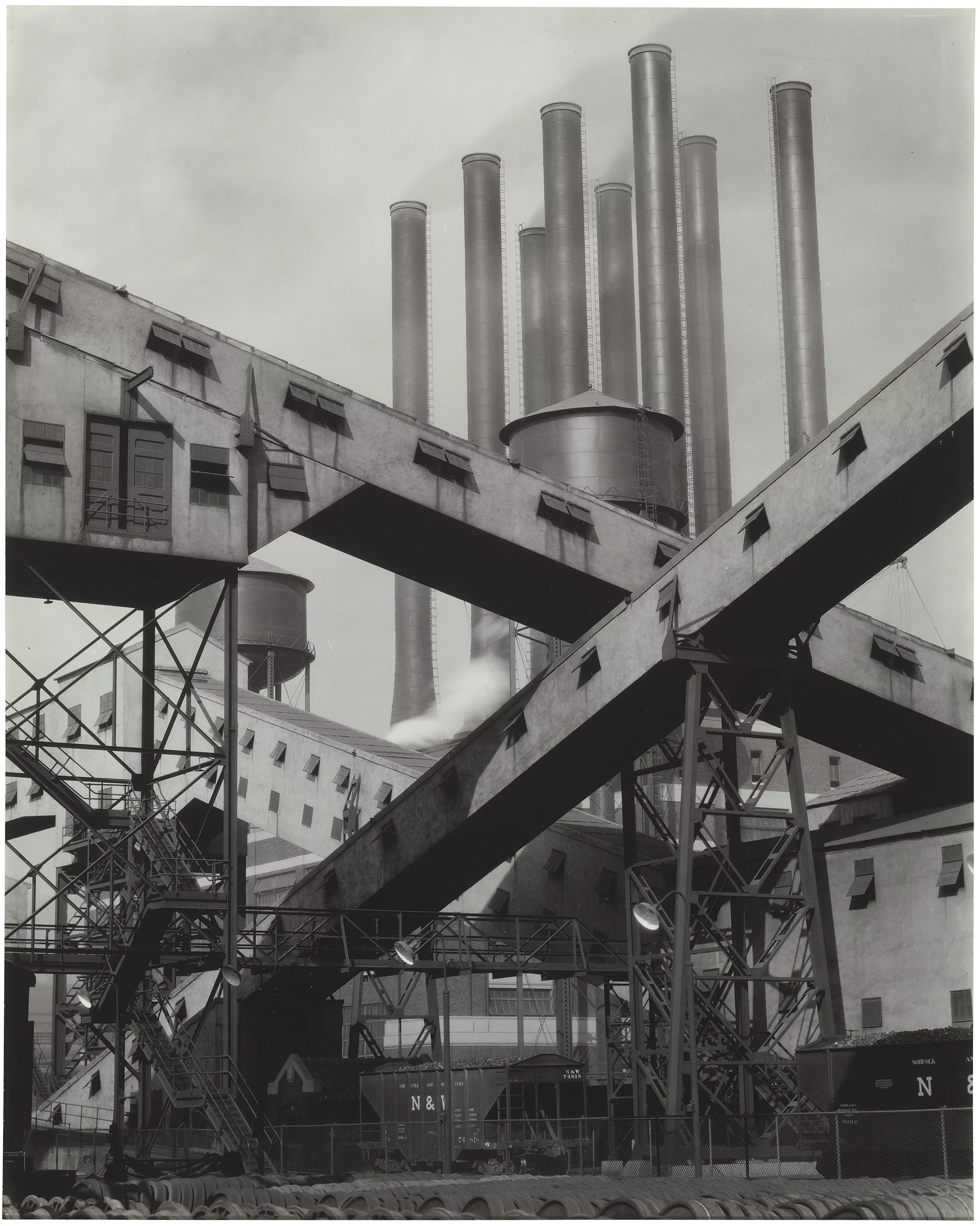

Precisionism was the first modern art movement born in the United States, and it didn't start with a manifesto or discussions over absinthe. Precisionism began in a Ford Factory in Dearborn Michigan. 1927 was a big year for the Ford Motor Company. They were sunsetting the the model T, unveiling the model A, and putting the finishing touches on the new Ford River Rouge complex—at the time, the biggest largest integrated factory in the world. Ford knew the importance of PR, and commissioned the architectural photographer Charles Sheeler for an ad campaign documenting their new monument to American industry.

Sheeler was an excellent photographer and a classically trained painter, fascinated by both the clarity and formality of medieval artists and avant garde movements like Cubism. The Ford factory became Sheeler’s muse. After completing his commissioned photo series, Sheeler turned to painting, revisiting the factory from every angle in chilly, intensely formal paintings that the New York Daily Worker described with the backhanded praise “Sheeler approaches the industrial landscape ... with the same sort of piety Fra Angelico used toward angels ... In revealing the beauty of factory architecture, Sheeler has become the Raphael of the Fords.”

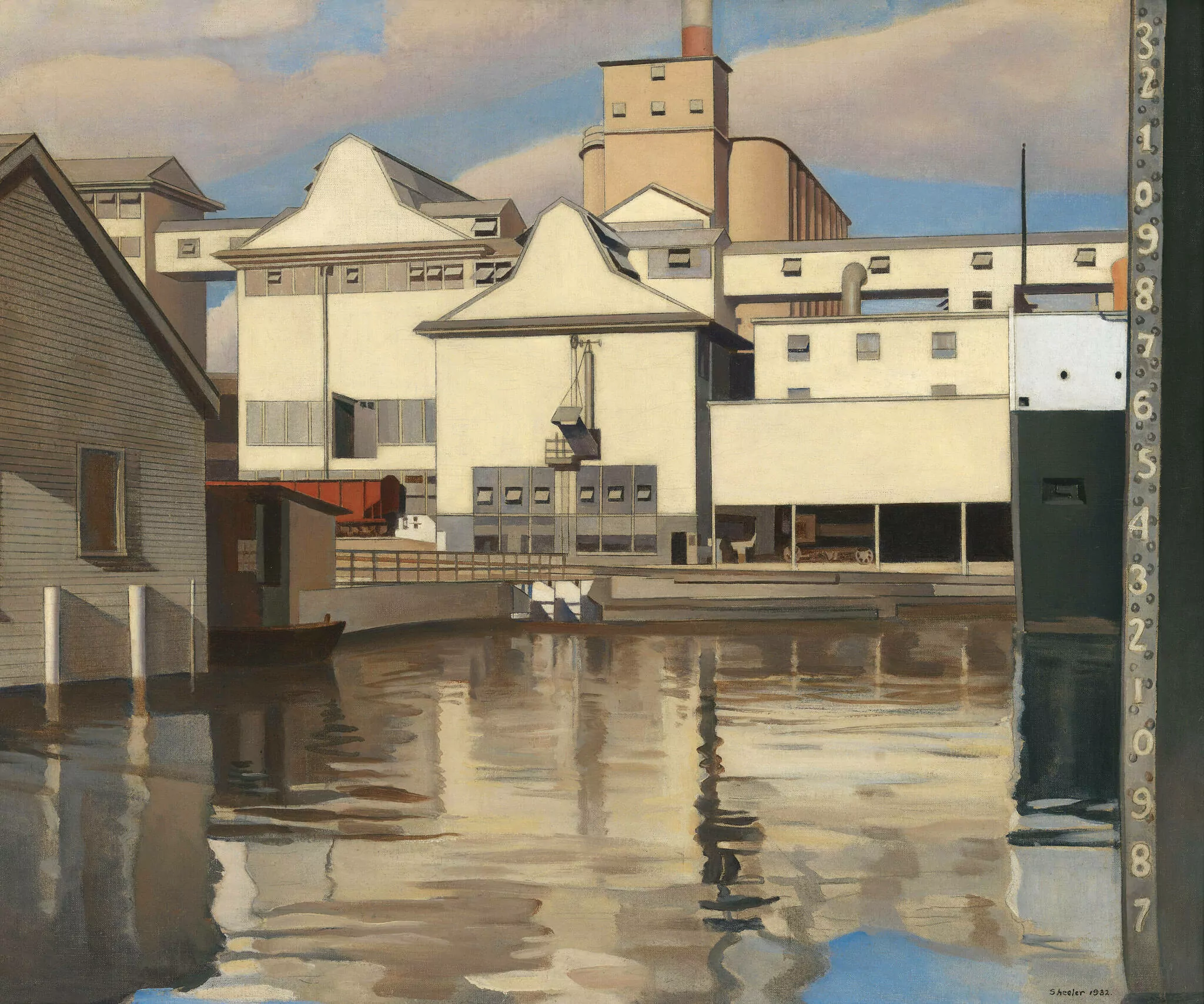

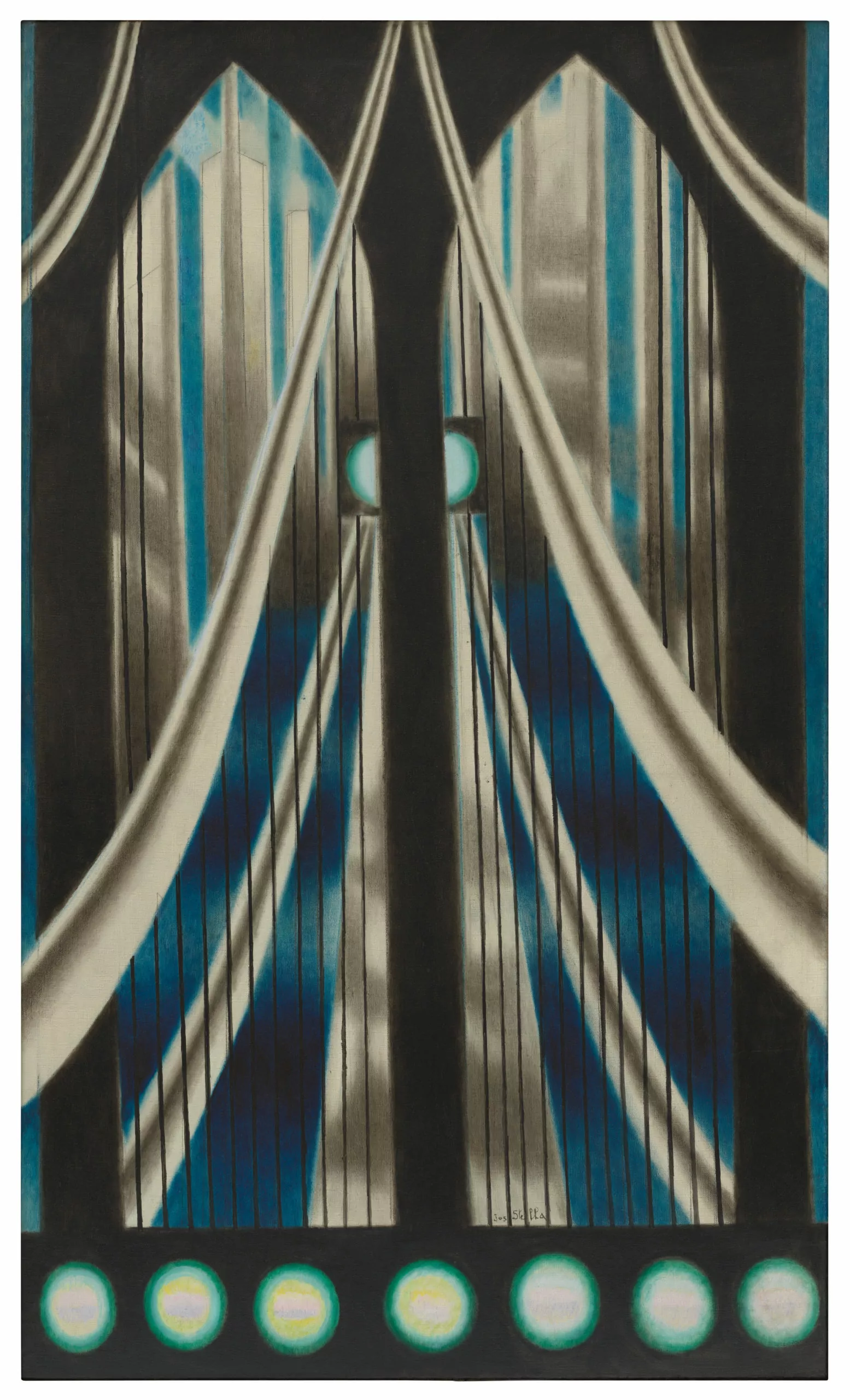

In the years leading up to his trip to the Ford plant, Sheeler’s style was evolving from Cubism and Futurism into something more uniquely American. Flat colors, graphic shapes, skyscrapers, industrial machinery as monuments, and never, ever people. And it wasn't only Sheeler. The photographer Paul Strand transformed urban spaces into minimalist realism with his 1915 photograph Wall Street. Joseph Stella used the Brooklyn Bridge as an alembic to distill his style from futurist bombast into something more like sacred geometry. And Charles Demuth was simplifying the water towers and granaries of rural America into towering, rusty building-blocks. In the way the Hudson River School idealized the mountains and valleys of the American West, these artists borrowed Cézanne’s approach to simplifying forms to transmute the human-built environment into the sublime.

In the early 1920s the artists developing this new style were referred to as the Immaculates or modern classicists for their smooth brushwork and idealized, minimalist forms, until Alfred H. Barr, then director of the MOMA in New York, coined the term “Precisionists” in 1927. The name combined with Sheeler’s revelatory experience at the ford factory, solidified a decade of artistic experimentation into a recognizable movement. Over the next two decades dozens of American artists expanded Precisionism’s style and subject matter. Louis Lozowick created Precisionist lithographs, John Storrs’s made precisionist sculptures, and Georgia O'Keeffe took the Precisionist style back to nature, rendering flowers, landscapes, and cow skulls in silky-smooth tones.

Precisionism is a strange movement to view with a modern eye. A century of industrialization has left world perched on the edge of climate collapse, and at least for me, the smokestacks of the River Rouge Ford factory inspire only existential dread. The resolute emptiness of these spaces imply the sterility of automation and the minimalist forms begin to feel malicious, alien. A buildings without occupents doesn't need windows. And without writings, letters, or dialogs making their subject matter more explicit, the entire movement is left feeling vacant. The Precisionists imagined an ideal world, but it’s only perfect when we aren't there.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Precisionism? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.