How do you capture the human ideal—the best of our courage, poise, grace and dignity? With the naked human body, of course. While nakedness is part and parcel with human experience, when bathing, changing, and having sex, the nude in art claims to present the naked body as allegory, showcasing physical perfection as a reflection of spiritual or intellectual perfection. But does it? British historian Kenneth Clark summed up the traditional distinction between naked and nude in his book The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, writing: “To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition. The word ‘nude,’ on the other hand, carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone. The vague image it projects into the mind is not of a huddled and defenseless body, but of a balanced, prosperous, and confident body: the body re-formed.”

The body as an apolitical utopia—sounds pretty great doesn't it? But as always, art and its history is messier than that.

Nudity in art is arguably as old as art itself, with ancient sculptures now referred to as venuses depicted naked, and sporting enlarged genitals and breasts. The 40,000 year old Venus of Hohle Fels, the oldest known depiction of the human form, is nude, with dramatically exaggerated reproductive features—a graphic image of neolithic ideals. But while the human body has been represented and venerated since the Neolithic, we owe the ancient Greeks for our modern understanding of the nude, specifically their sculptures of male athletes. The Greeks loved a beautiful man, and inspired by Egypt’s monumental sculptures they developed an entire genre of nude male sculptures called Kouroi around 600BCE. The female nude appeared later, when the sculptor Praxiteles was commissioned to create a bathing, but clothed Aphrodite, and created a second version in the nude, which became the patron symbol of Knidos, the city who purchased her.

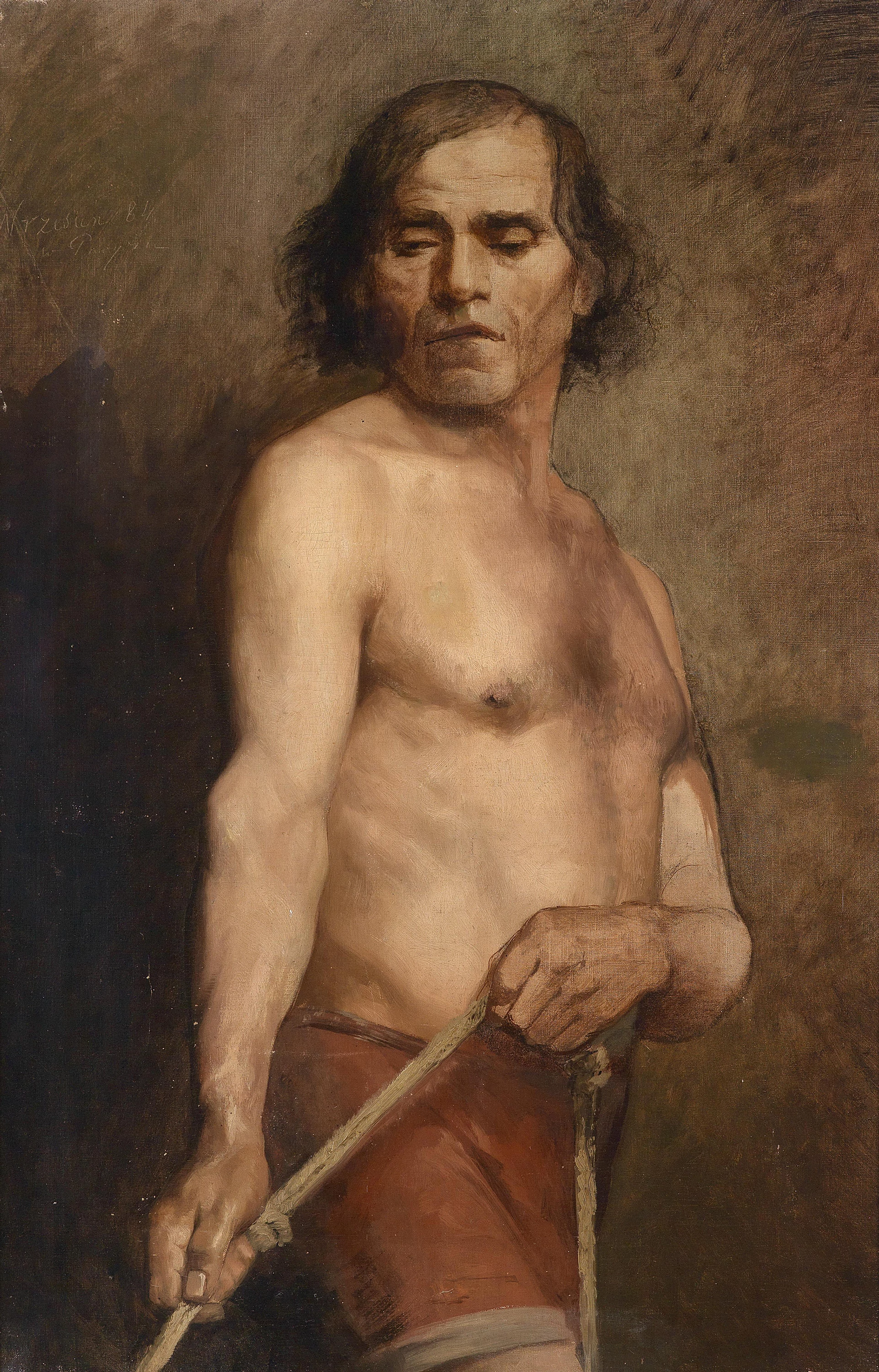

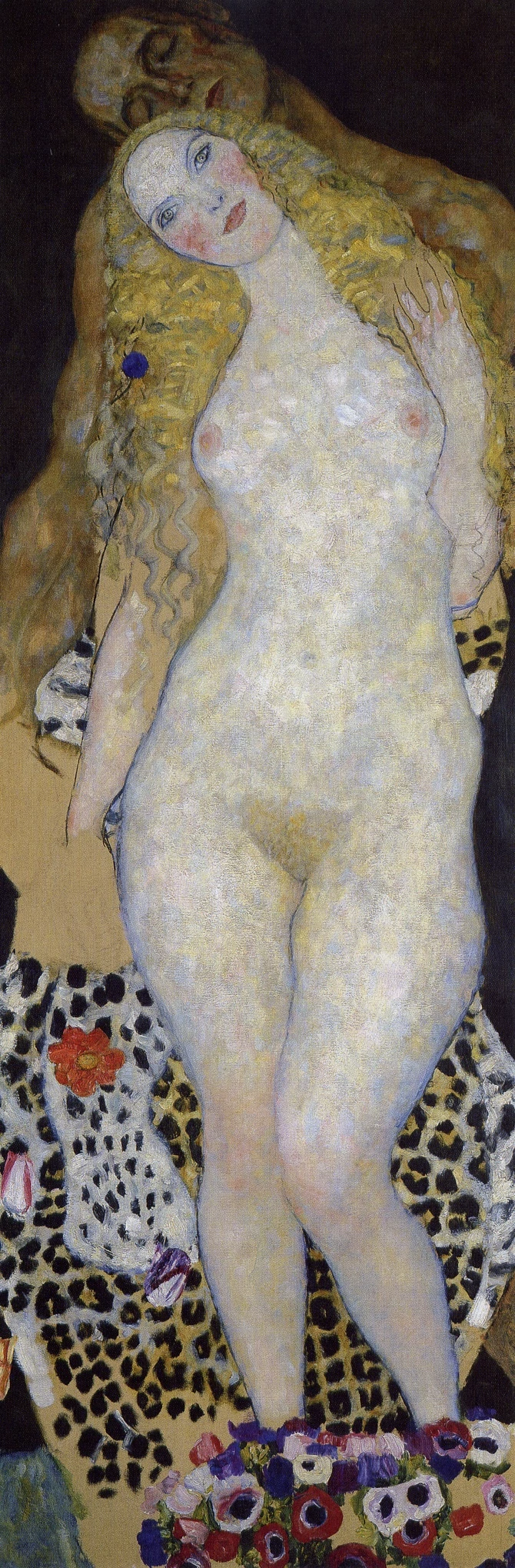

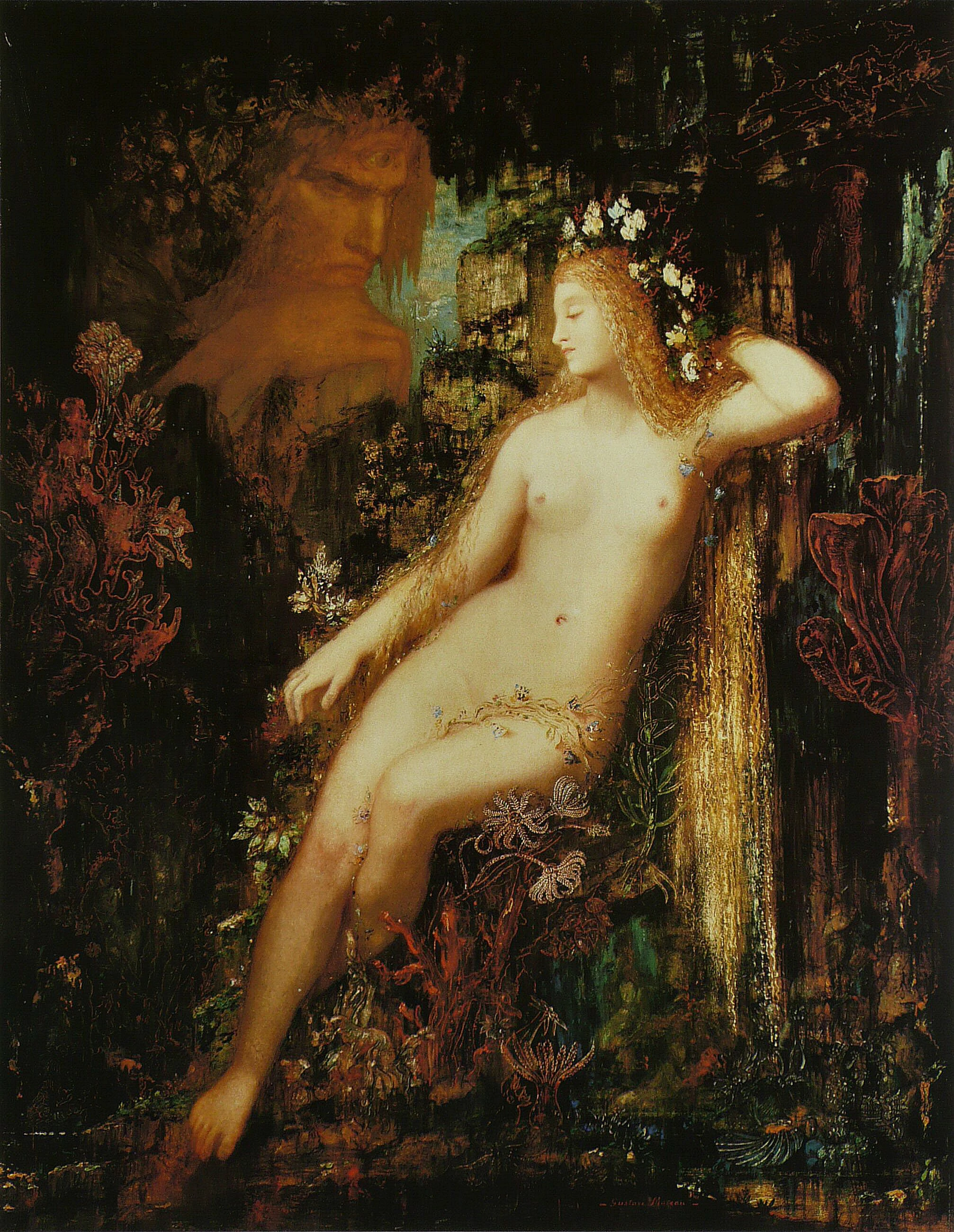

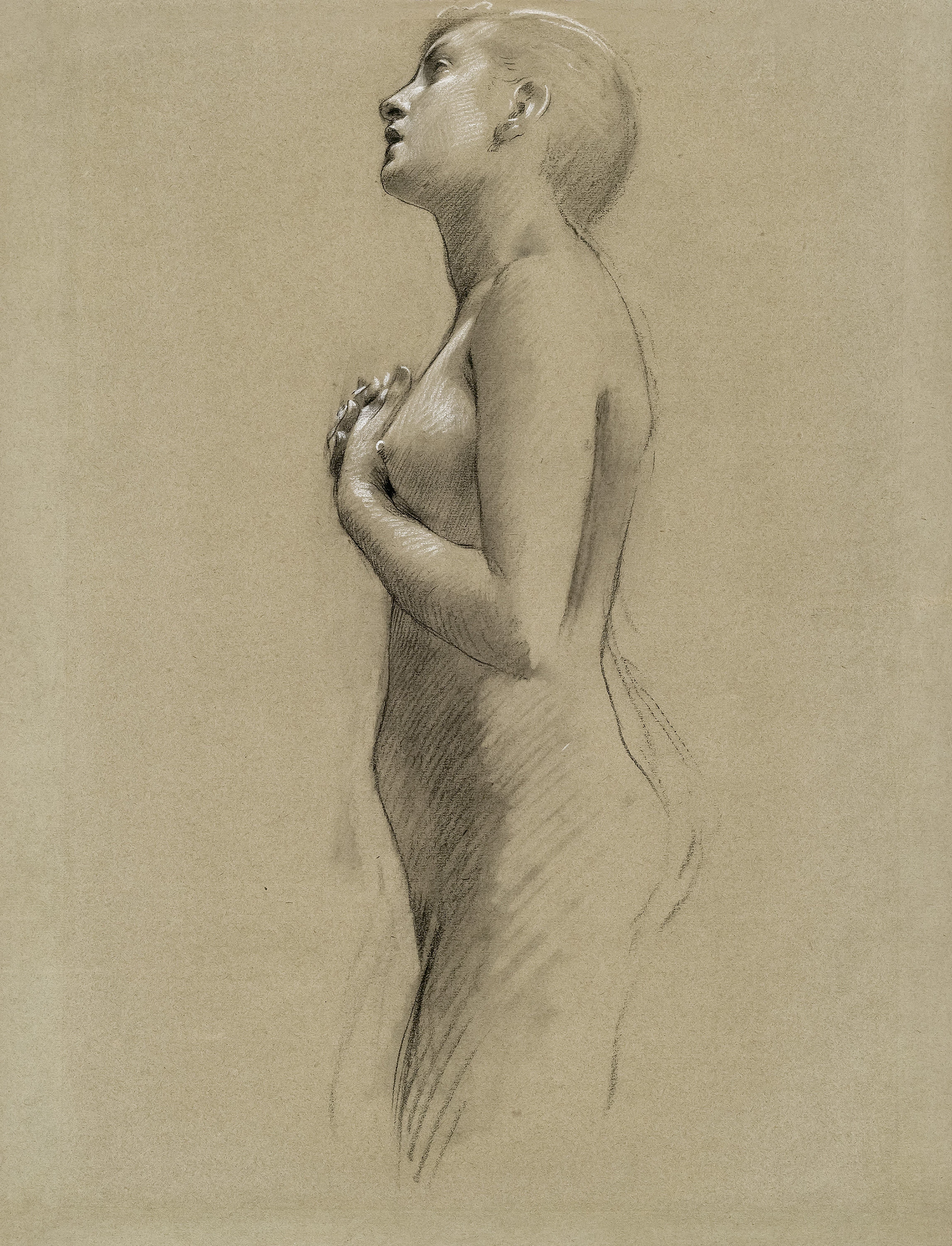

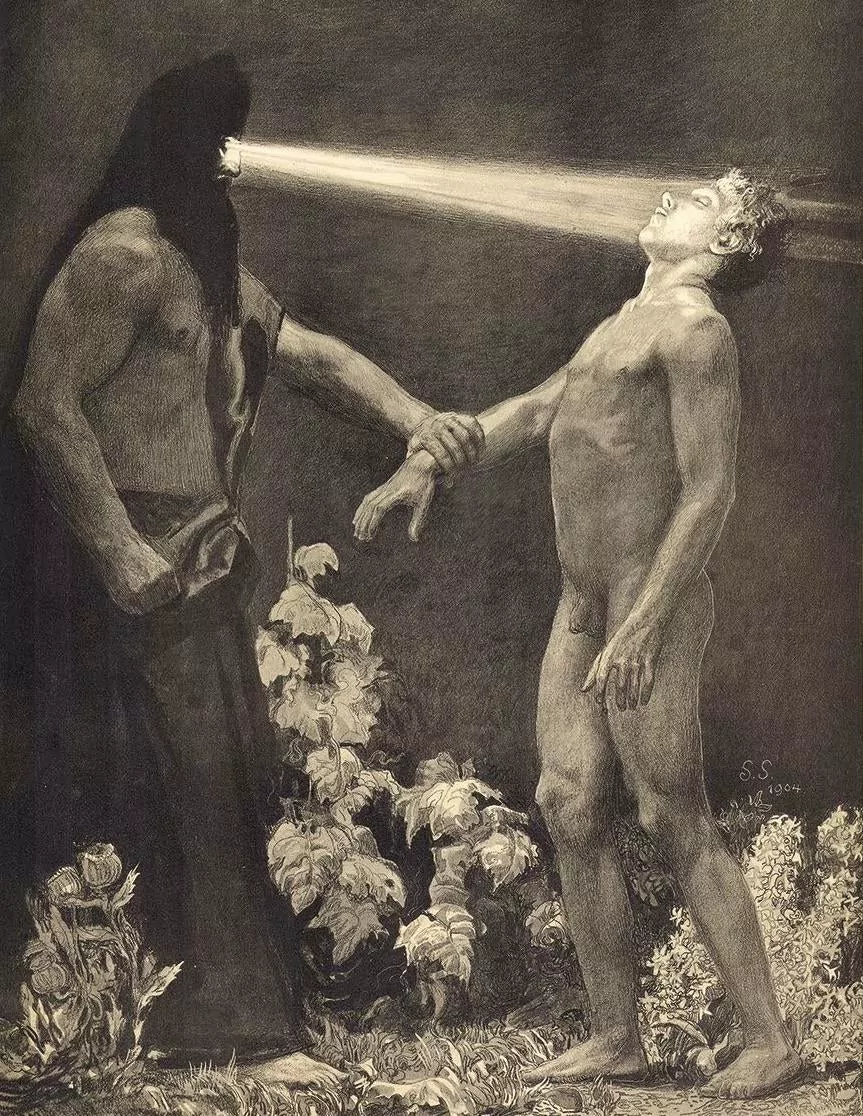

Though the Greek Kouroi and the Aphrodite of Knidos were created more than 2300 years ago, they established a gendered presentation that persists to this day. Kouroi depict fit young men—their nakedness is unconscious and un-sexualized. Perfected symmetry and proportion describe their physical capability, and their nakedness expresses the conquest of intellect over inhibition. Exposing the male body conveys the subject’s nobility and invulnerability. In contrast, Aphrodite delicately covers her pubic area in a gesture that became so common it was termed the pudica or ‘the modest pose.’ Aphrodite is aware of her nudity, and guards herself from the sexualized gaze of the viewer. Her posture expresses reservation, even vulnerability. Kouroi defined the form now called the heroic nude, while Aphrodite laid the foundation for the submissive nude. From the beginning, the message was clear—the male body was spiritually perfect, and the female body was sensually perfect.

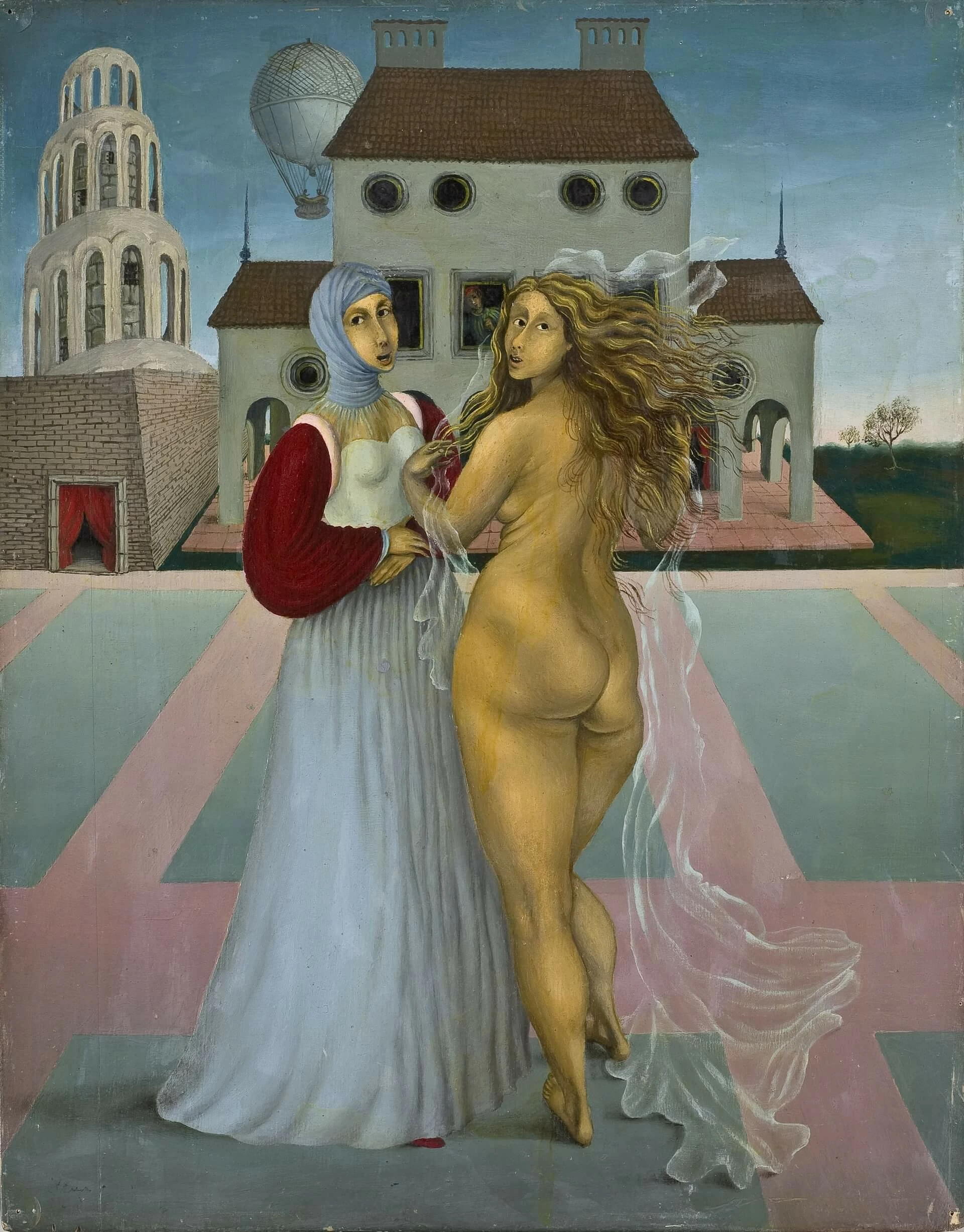

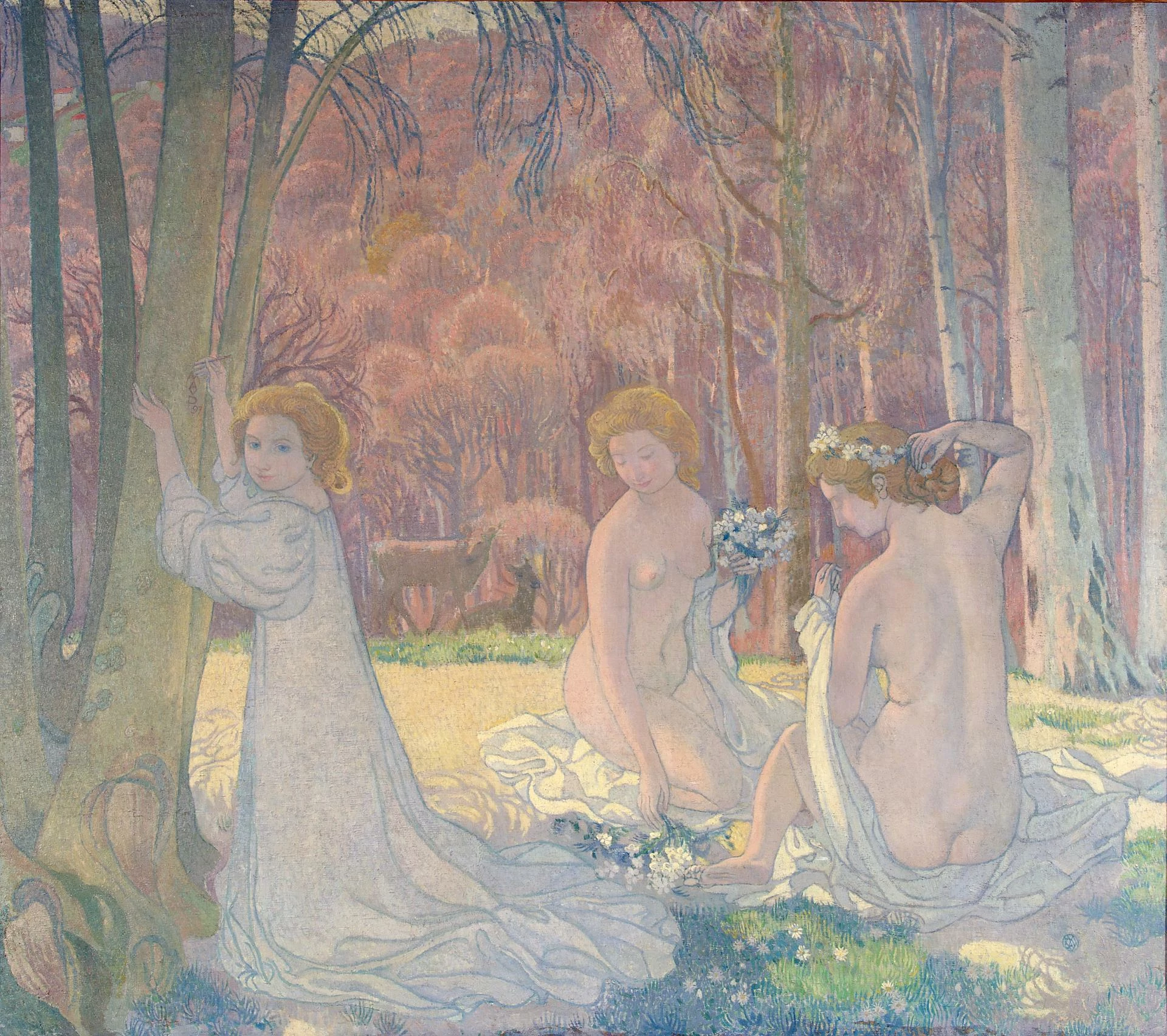

After the Medieval Christian world’s emphasis on chastity and celibacy kept most bodies clothed for a few hundred years, the nude was reborn in western art during the Italian Renaissance. Artists looking to Greco-Roman art and philosophy for inspiration, expanded the tropes of heroic and submissive nudes to decadent extremes. Michelangelo transformed biblical saints into nude beefcakes, and his monumental David is both perfectly dignified and physically appealing. Jacques-Louis David’s The Intervention of the Sabine Women turned historical figures into nude superheroes, the beaded Tatius even wears a cape!

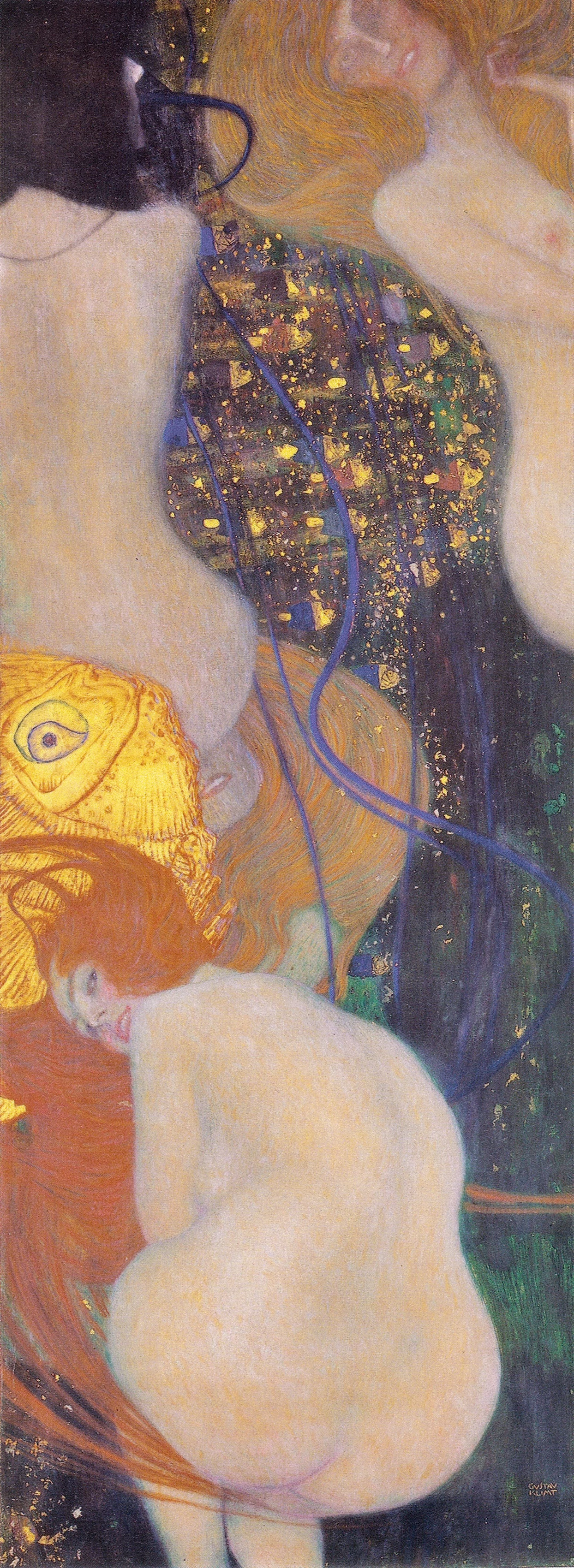

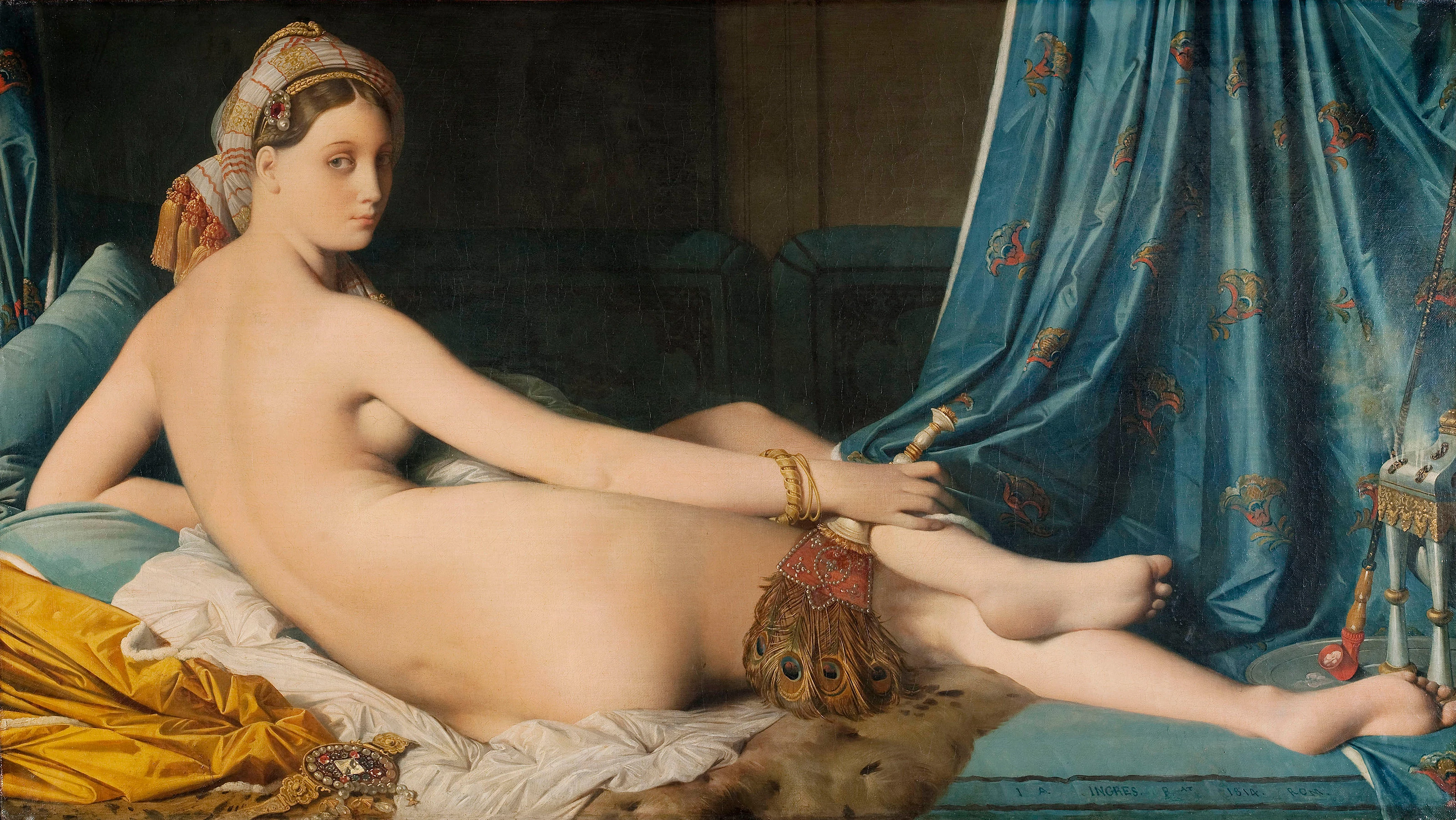

If the heroic nude was exaggerated during the Renaissance, the submissive nude was eroticized to an entirely ridiculous degree. Titian’s Venus of Urbino is not only reclining on rumpled sheets and gazing invitingly at the viewer, but her hand covering herself in the traditional pudica gesture might instead be touching herself sexually.

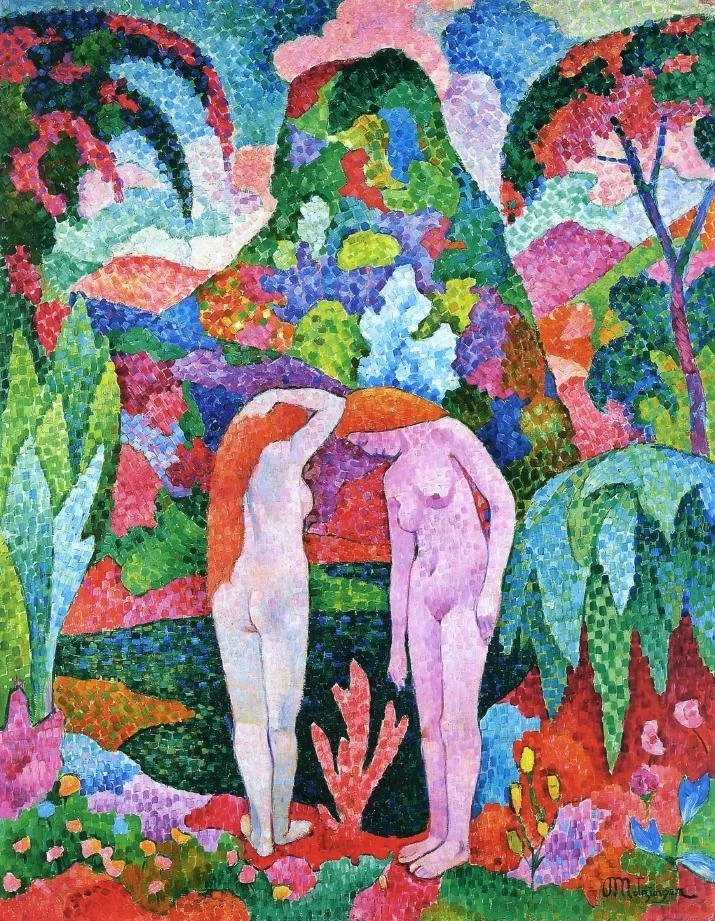

And so on through the Baroque and Rococo movements. Peter Paul Rubens’ voluptuous female bodies led to the term Rubenesque, and François Boucher set his nudes in paradise gardens overflowing with lavish velvet and greenery. It seems like most figures in Renaissance painting are nude, but they sure are cheerful about it.

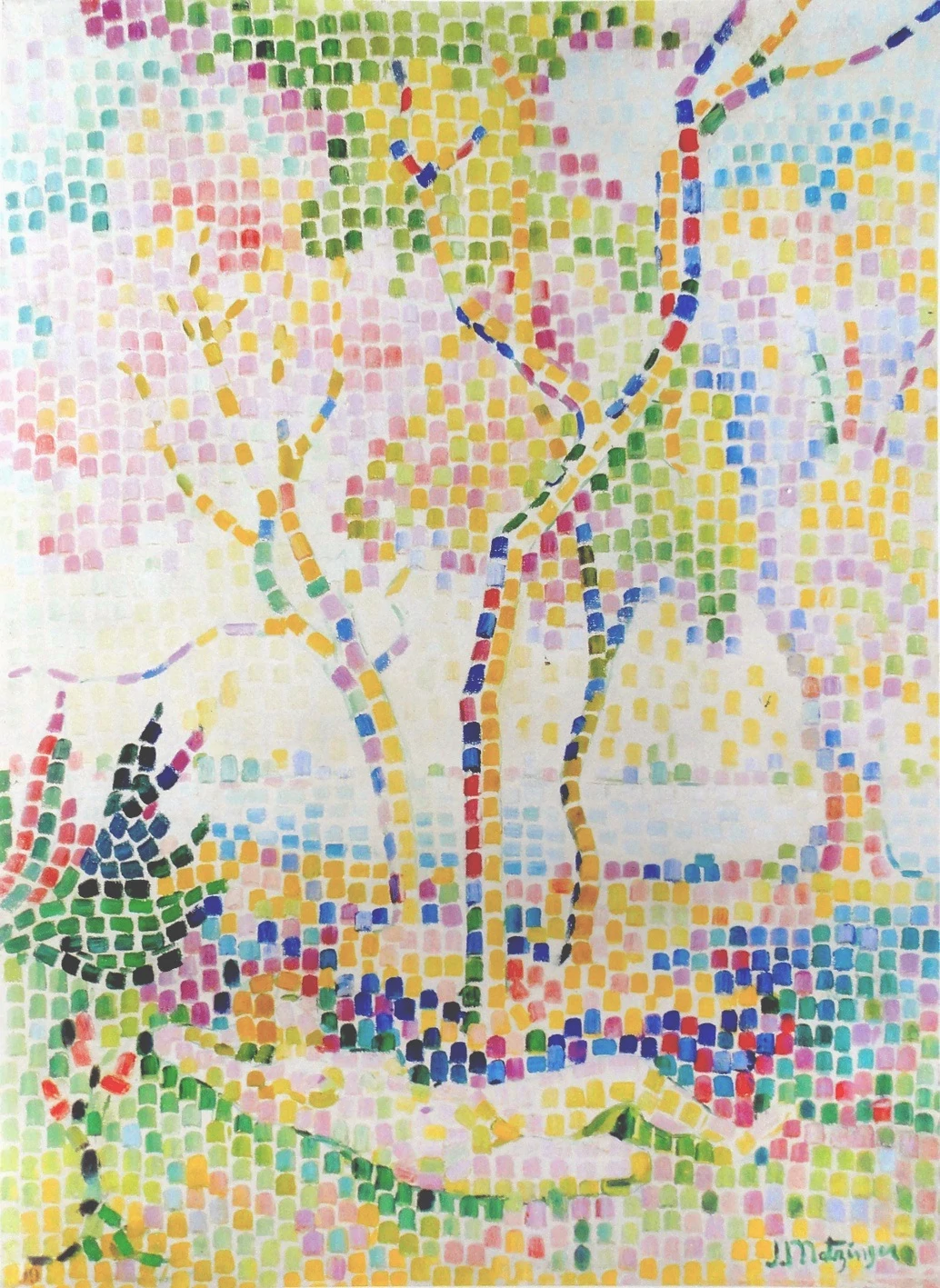

The nude is a largely Western idea, a classical aesthetic form adopted and gleefully expanded on by artists desperate for a way to circumvent the strict Christian mores of their dominant culture, and an excuse to justify the challenge and emotive reward of painting the human form unencumbered. But as you'd expect, the naked body has been represented in cultures all over the world, and examining examples from two cultures where nakedness was represented differently will hopefully clarify why ‘the nude’ could only appear in cultures with very specific hangups.

Sometime in the Muromachi era, between 1336 to 1573, or smack dab in the middle of the Italian renaissance, Japan was introduced to China’s carefully illustrated medical manuals. Naturally, the elegant line art style was immediately adapted to pornography. Called shunga meaning ‘spring,’ a euphemism for sex, these erotically themed artworks became highly valued, and by the Edo era, commonplace. Nearly every Edo artist created shunga alongside their other projects and it is said that every class of Japanese citizen enjoyed it, except perhaps the stodgy old shogunate.

So if explicit erotic art was entirely normalized in Edo Japan, what does that mean for the western nude? In their essay Sexuality in Japan, Kiyoshi Matsumoto writes that “Sexuality in Japan developed separately from that of mainland Asia, as Japan did not adopt the Confucian view of marriage.” Without a strict religious code to enforce chastity, Japanese culture was unconcerned by sexual expression, and had exhibited phallic objects as sacred since their prehistoric era. Matsumoto continues to say “Shunga depicted sexual pleasure that included both heterosexuality and homosexuality, each not only acknowledged but also encouraged.” Honestly even today we're barely that woke.

If you're familiar with the Yoni and Linga, you’ll know where this is headed, but we’ll start with this: in the words of Kishore Singh, art critic and director of Delhi Art Gallery, “Traditionally, the unclothed body did not really excite comment; the clothed body was not really part of our tradition. For instance, a garment like the blouse only came into use 200 years ago.” Meaning nakedness was super normal through most of India’s history of art.

A modern cousin to the heroic nude, monumental nudes display the body at an architectural scale, and not only literally. The figure in Abaporu by Tarsila do Amaral appears colossal from its stretched perspective, and Tamara de Lempicka’s The Beautiful Rafaela in Green simplifies and smooths the figure to make a small canvas depict a vast landscape of flesh.

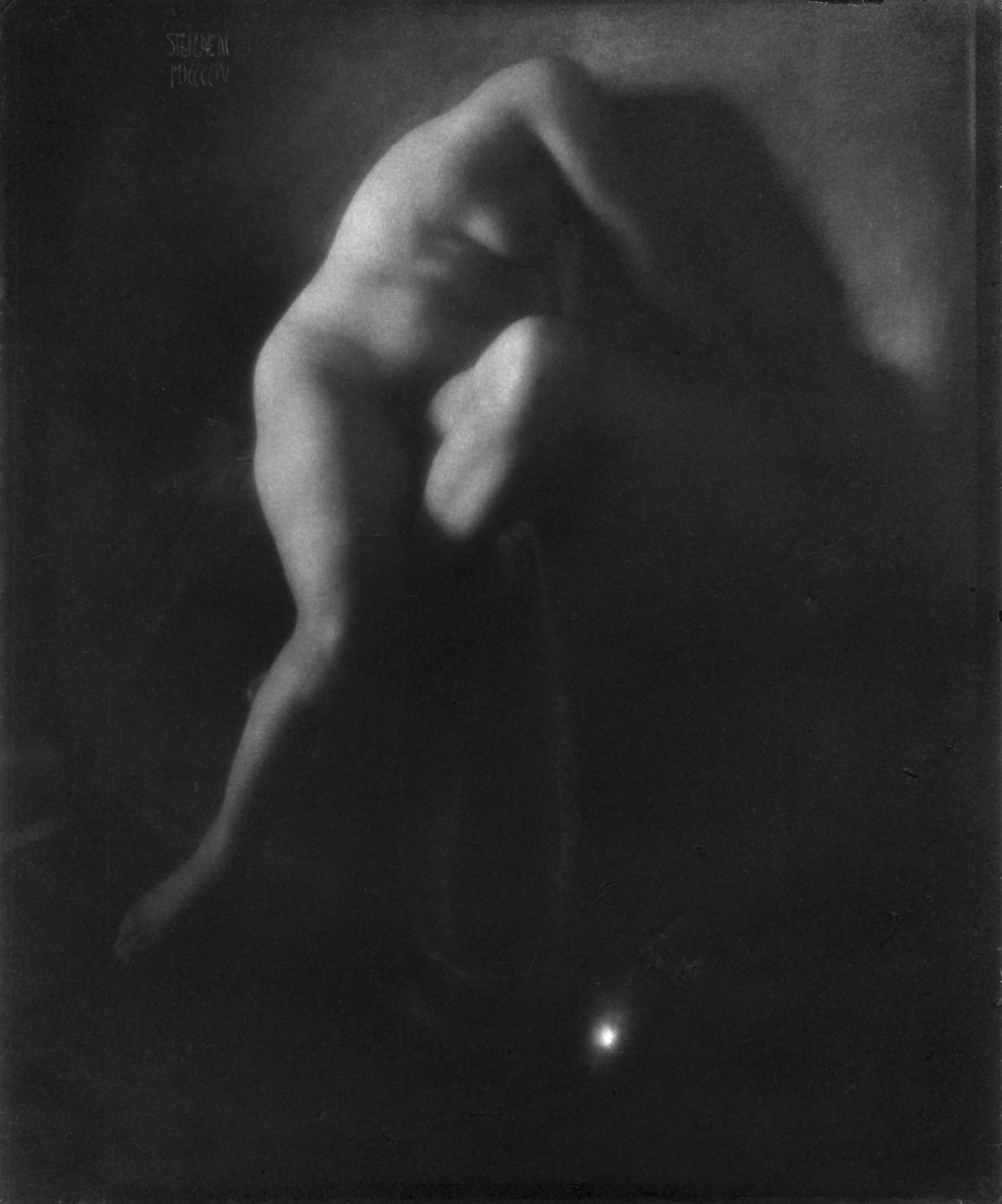

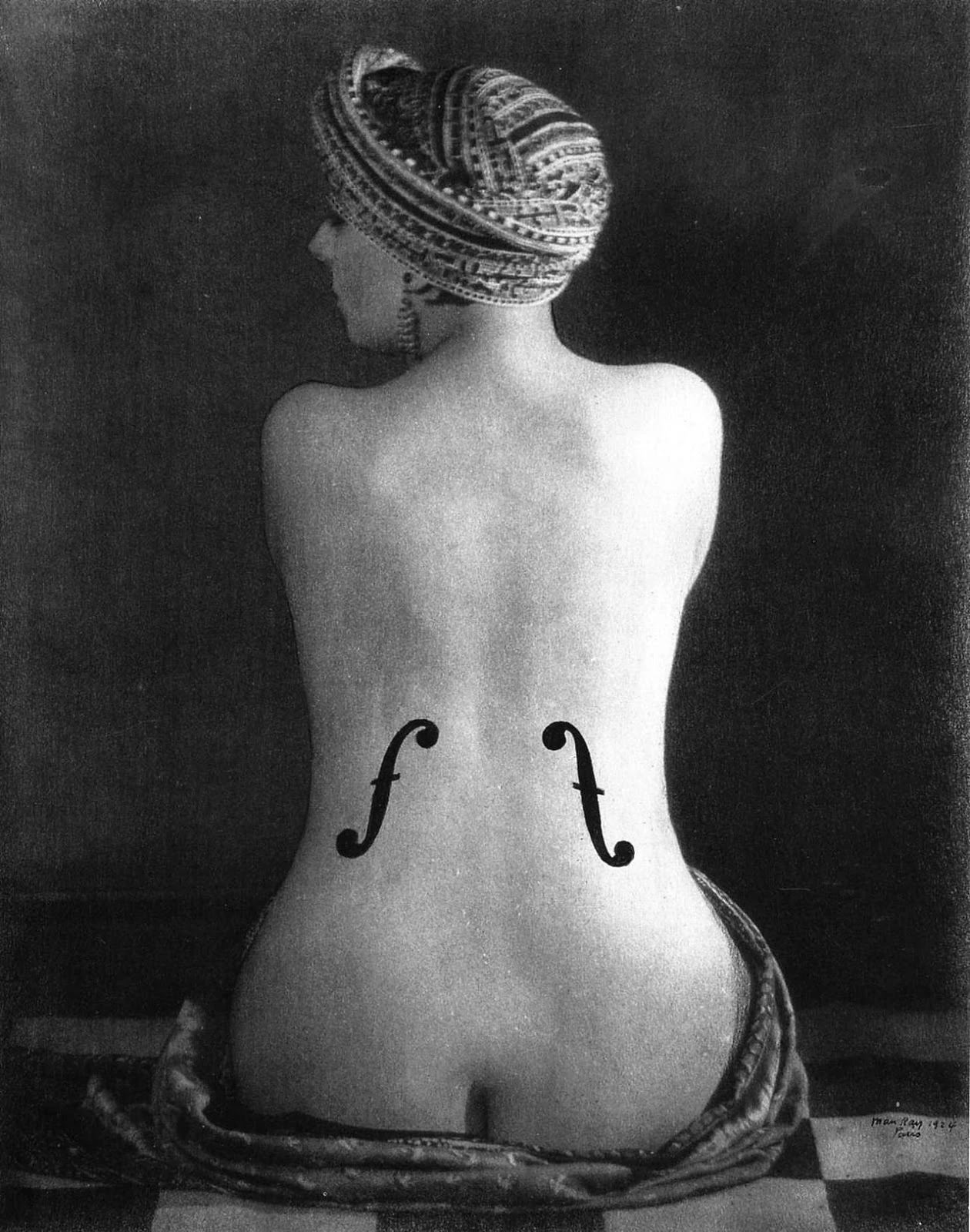

The classical nude is has no awareness of the viewer’s gaze. They exist in a narrative snapshot preserved for our appreciation. But more recent artists have disrupted this pattern with subjects who meet the viewer’s eye. In The Nude Maja, Francisco Goya’s anonymous subject is fully aware and unashamed. Going further, Nude Girl by Gwendolen Mary John looks exhausted from the scrutiny, and The Marchesa Casati by Romaine Brooks presents herself ominously, seemingly weaponizing her nakedness.

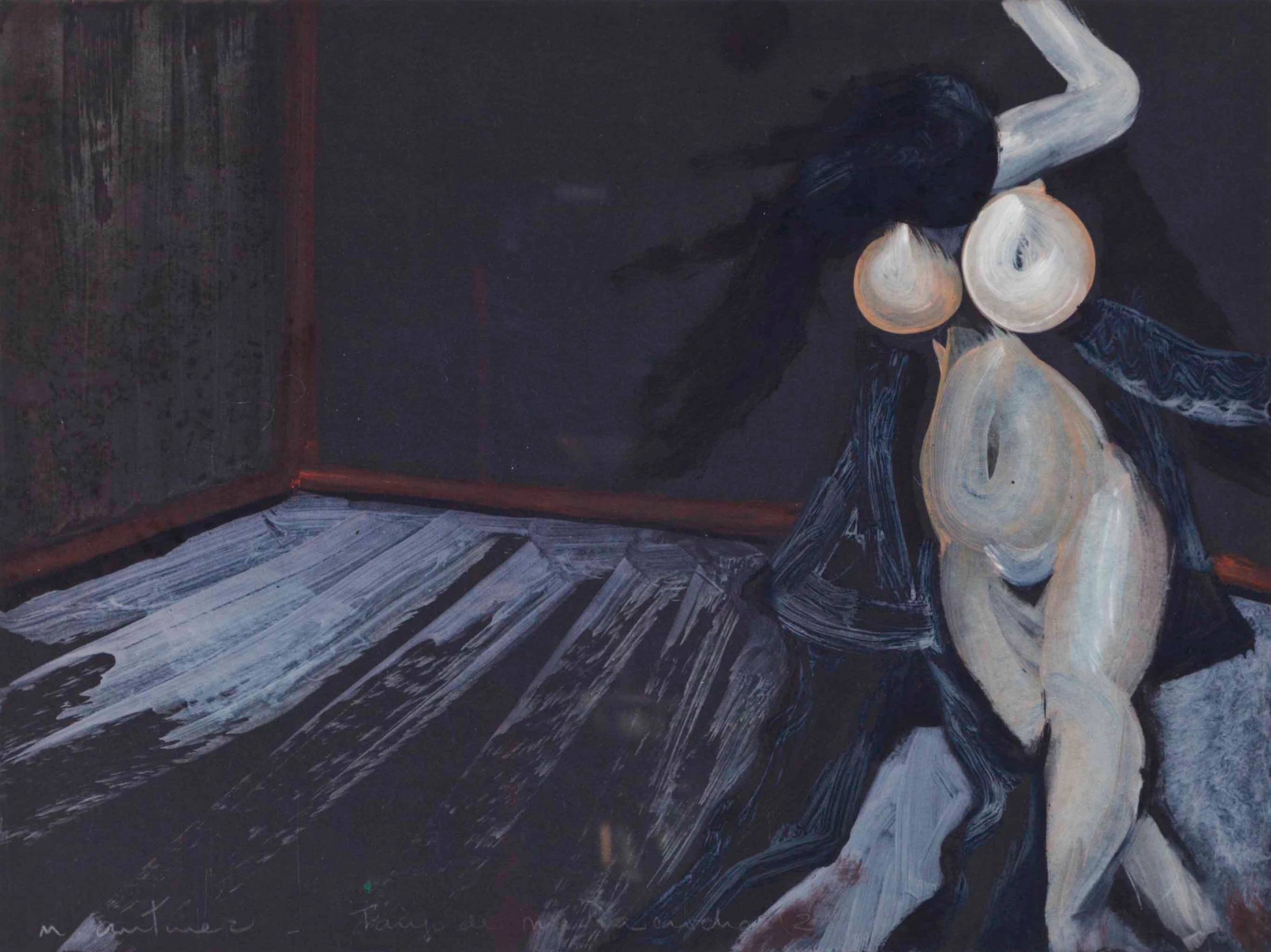

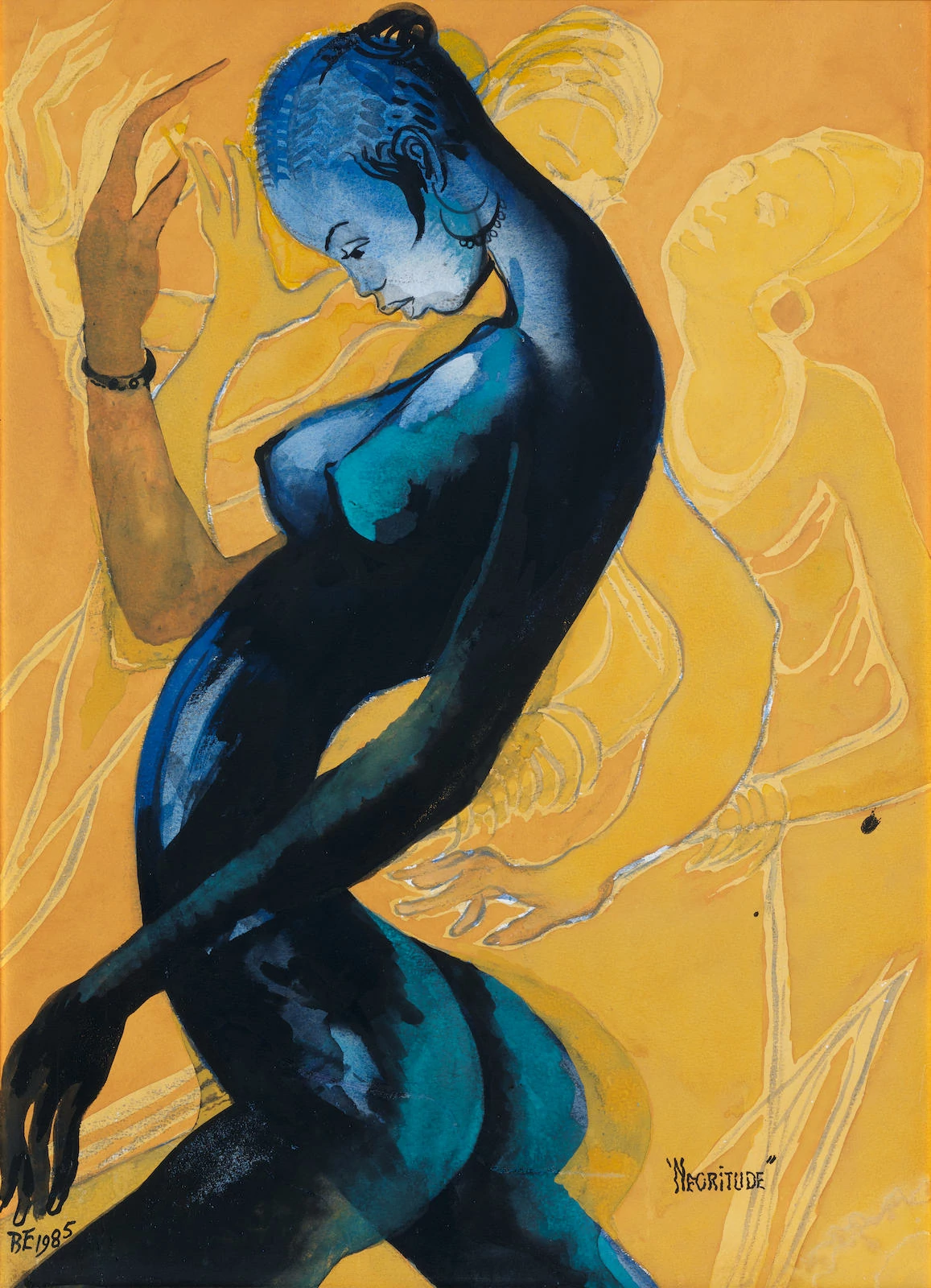

The body in motion is a unique challenge for painters and sculptors. Ben Enwonwu distorts the body to capture movement in Negritude. Suzanne Valadon, well acquainted with bodily motion after a short career as an acrobat, combines three figures into a single implied motion in The Launch of the Net.

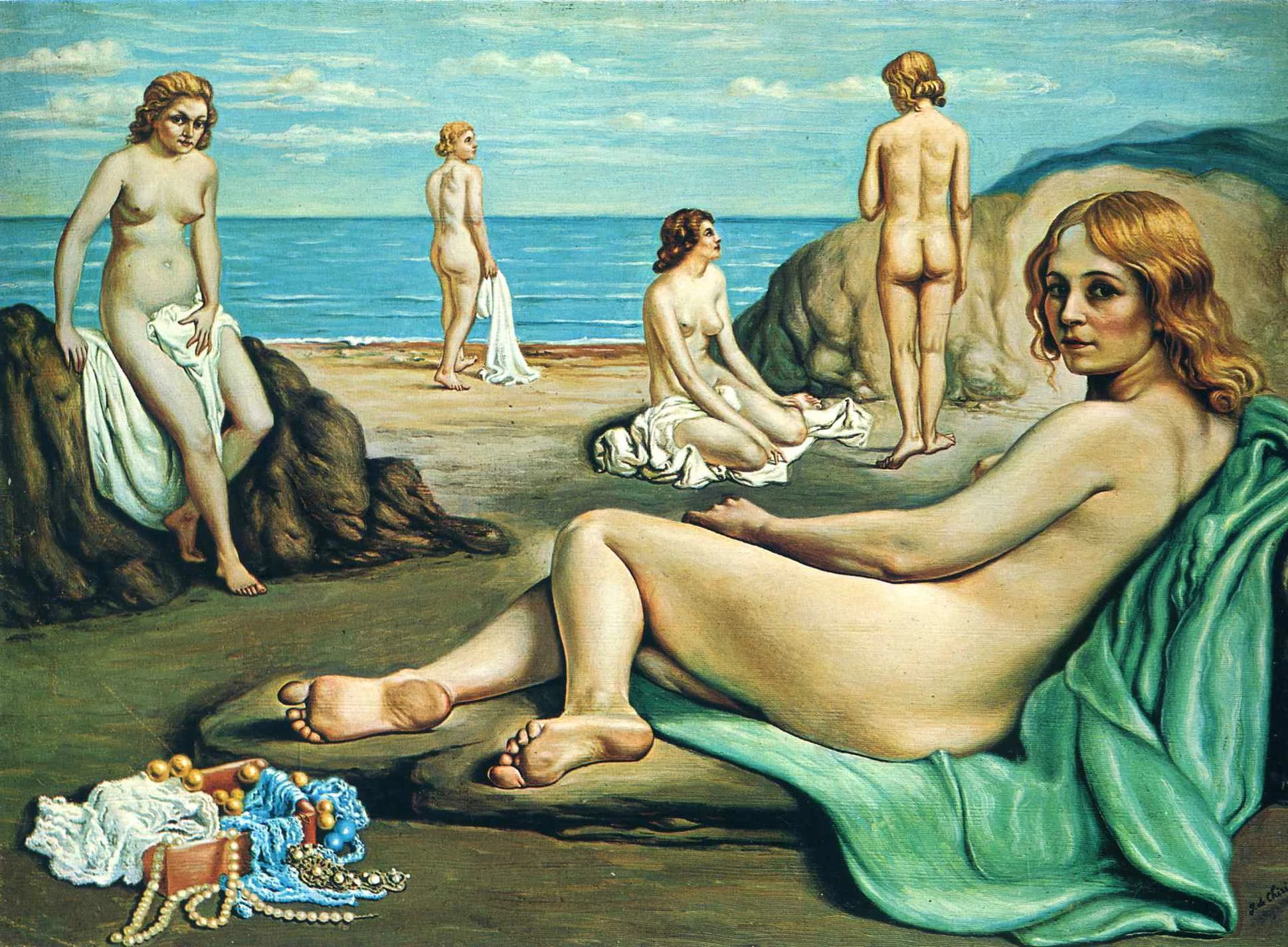

The reclining nude is ridiculously prevalent in art. Honestly it’s just everywhere. And while casual, daytime repose can certainly be considered an ideal of relaxation, the truth is more lascivious. The theme of nude women draped languorously over furniture exploded in popularity during heyday of Orientalist art, and were referred to as odalisques, originally a term for female slaves in Turkish harems. Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s The Tepidarium is a perfect example, but there are many, many more. Manet interrogated the form in Olympia, where the nude subject is clearly a prostitute, and the visitor is placed in the position of their John. But subversion only goes so far, and it’s difficult to rationalize a reclining nude as anything other than a titilating display of sexual availability.

...

As contemporary viewers of art, it’s useful to ask the question “who is this art for?” The nude is a complicated theme because it claims to represent the best of humanity, yet cannot escape the biases and desires of the humans who create them.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about The Nude in Art? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.