Olga Rozanova

The intellectual mother of Abstract Expressionism

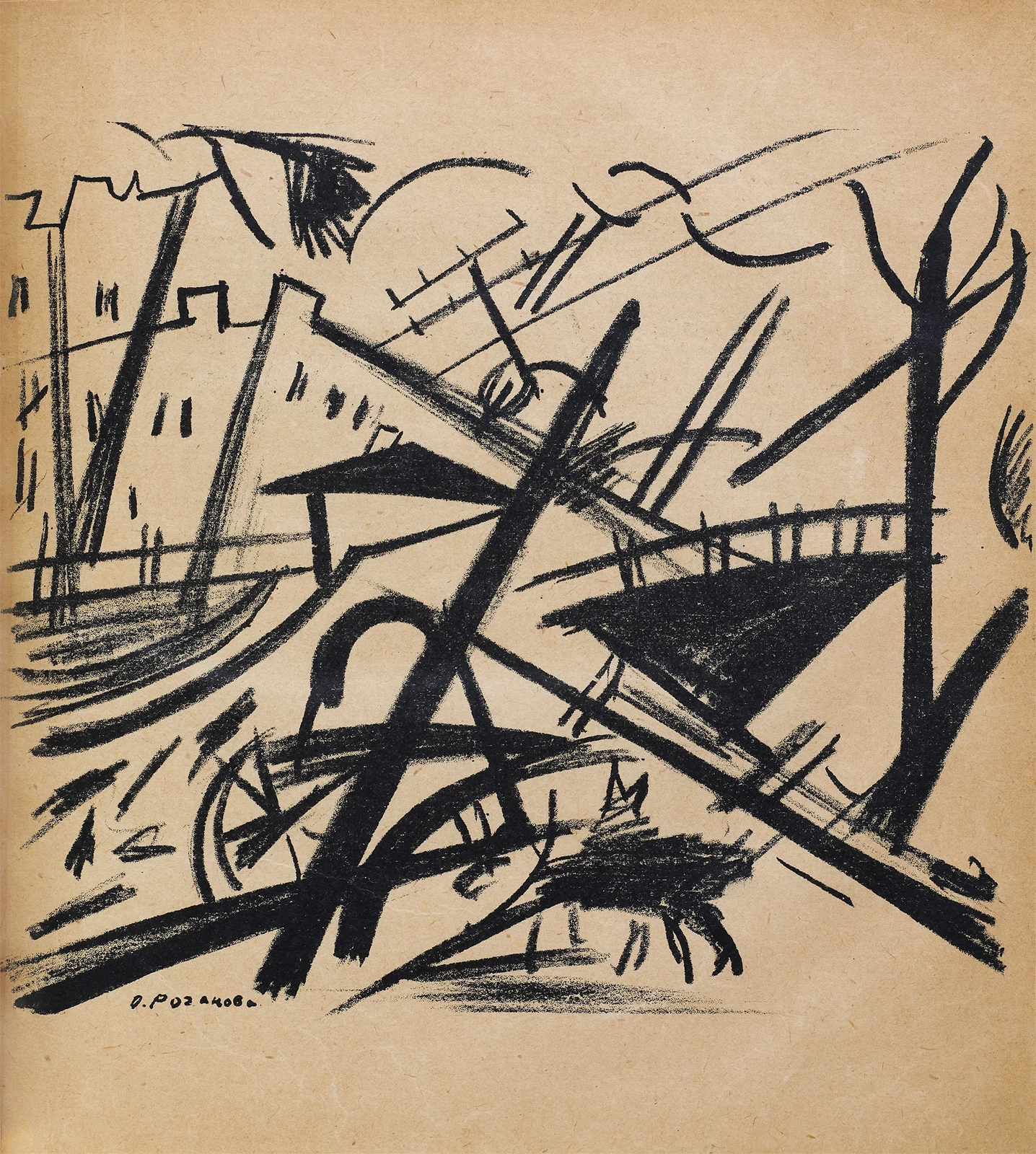

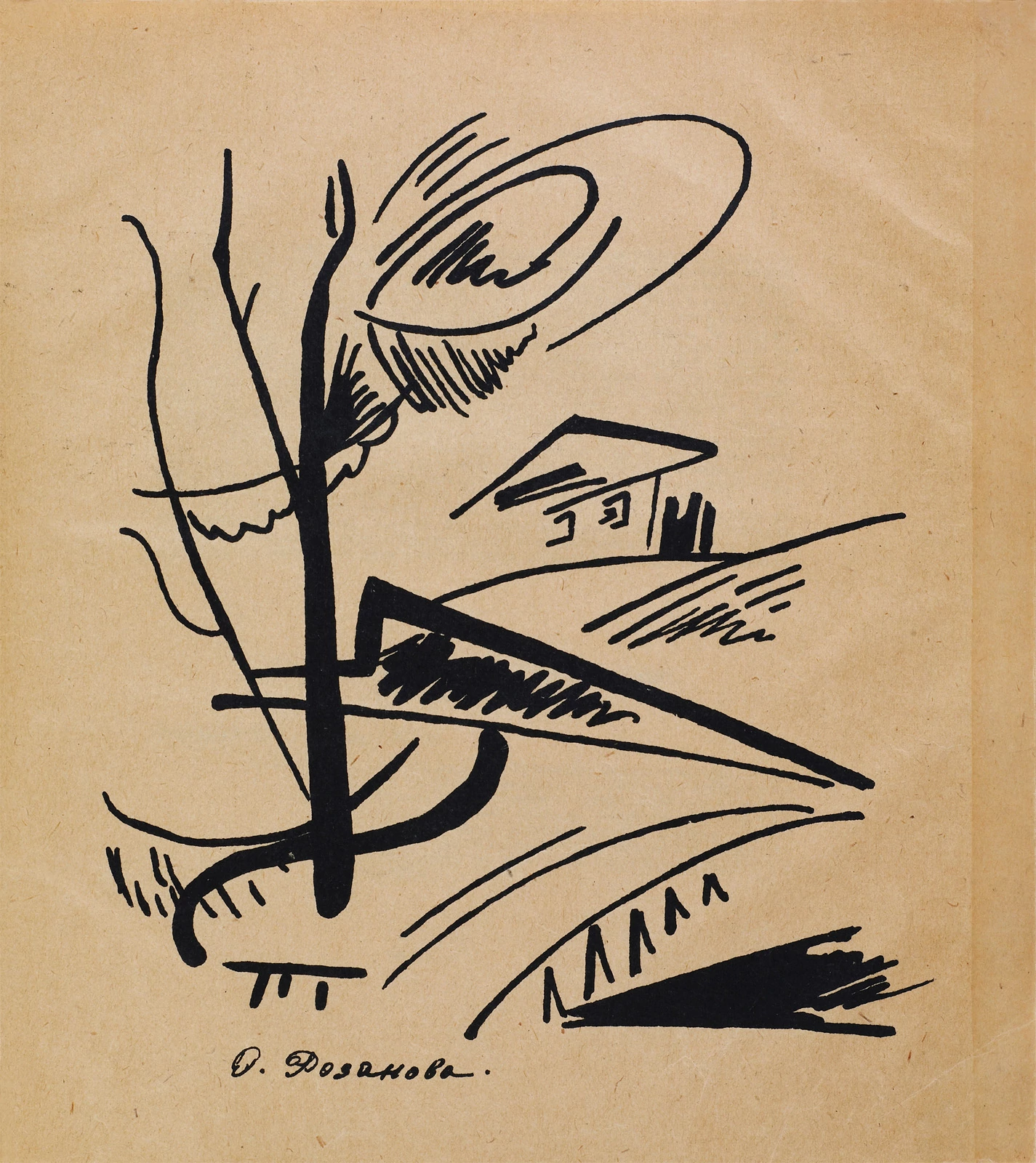

Olga Vladimirovna Rozanova burned hot and died young. Emerging from the provincial aristocracy of turn of the century Russia, she swept into Moscow with a focus and intellectual rigor that drew her immediately into the city’s artistic avant-garde. It was a heady time. A time for manifestos. Rozanova debated with the art group Soyuz Molodyozhi, the ‘Union of Youth,’ and experimented with the styles and theories of Italian Futurism in her works The City and Fire in the City, which impressed Filippo Marinetti, the founder of futurism himself. She blended futurism back into cubism in a series of playing card portraits that immortalized her fellow artists as kings, queens, and knaves.

In 1912, Rozanova met the poet Aleksey Kruchonykh, her future husband, and illustrated his indecipherable Zaum poetry, Futurism’s trans-rational language of pure expression. Then suddenly, futurism was no longer enough. Rozanova joined Kasimir Malevich’s Suprematist group, diving into pure abstraction. Her vivid compositions expanded expanded the supremacist goals of expression without figures.

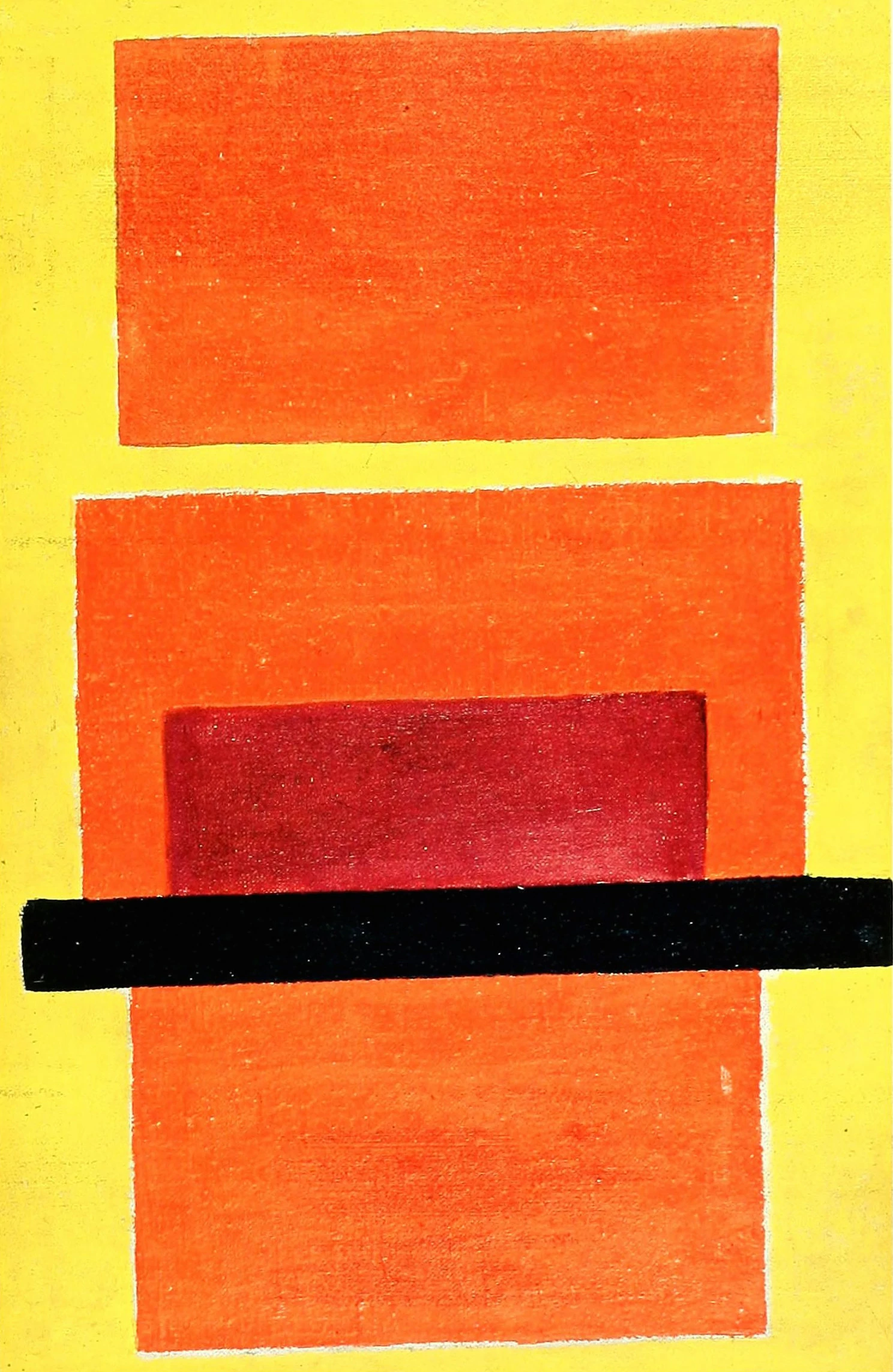

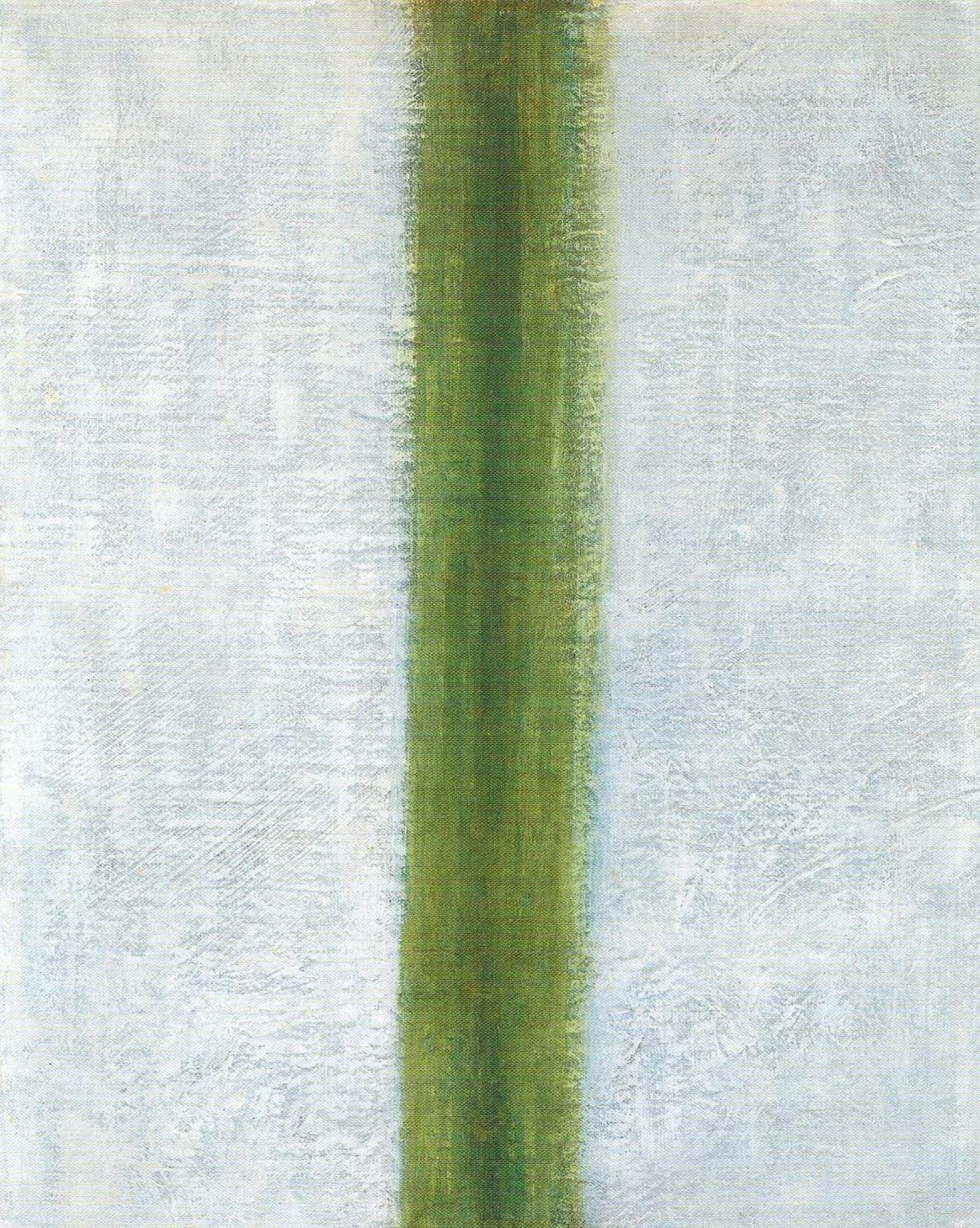

But Rozanova burned out. A weakened immune system left her victim to diphtheria, and she died in 1917. Her last works contain a final innovation: the fledgling concept of color painting—bold, radically simple canvasses that 30 years later influenced the Abstract Expressionist movement. Rozanova painted color fields before Rothko, and vertical lines before Barnett Newman. If only she'd lived a bit longer.

There is nothing more awful in the world than repetition, uniformity