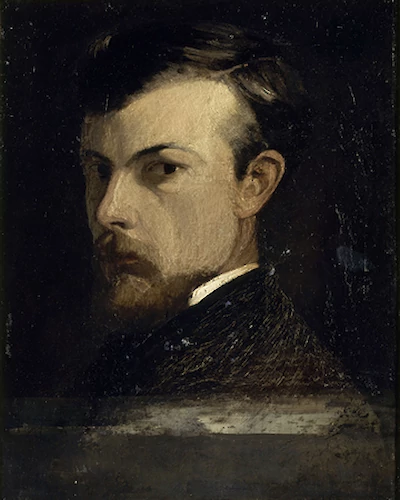

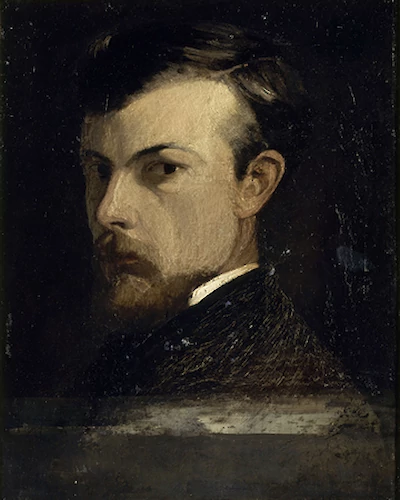

Odilon Redon

The faces we see in our dreams

Odilon Redon was born Bertrand-Jean Redon to a family of wealthy slave-traders. Concieved in New Orleans, but born in France, his youth was easy. Young Odilon, as his parents nicknamed him, drew and painted, and though he failed his entrance exams to the architecture program at École des Beaux-Arts, he dabbled in engraving, lithography, and sculpture through his 20s. It was the war that changed him.

“Charcoal does not allow kindness; it is sober, and only with real emotion can you draw results from it.”

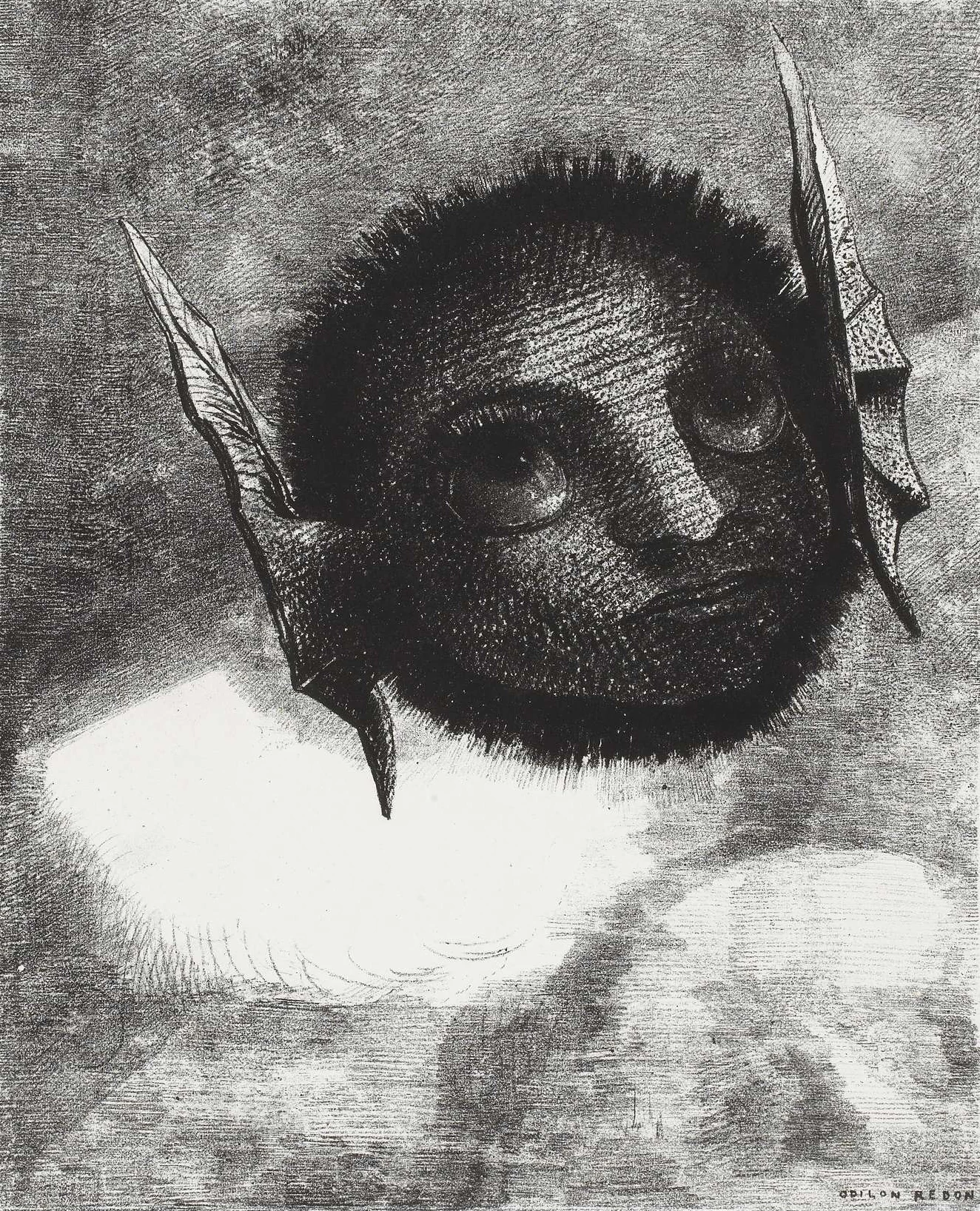

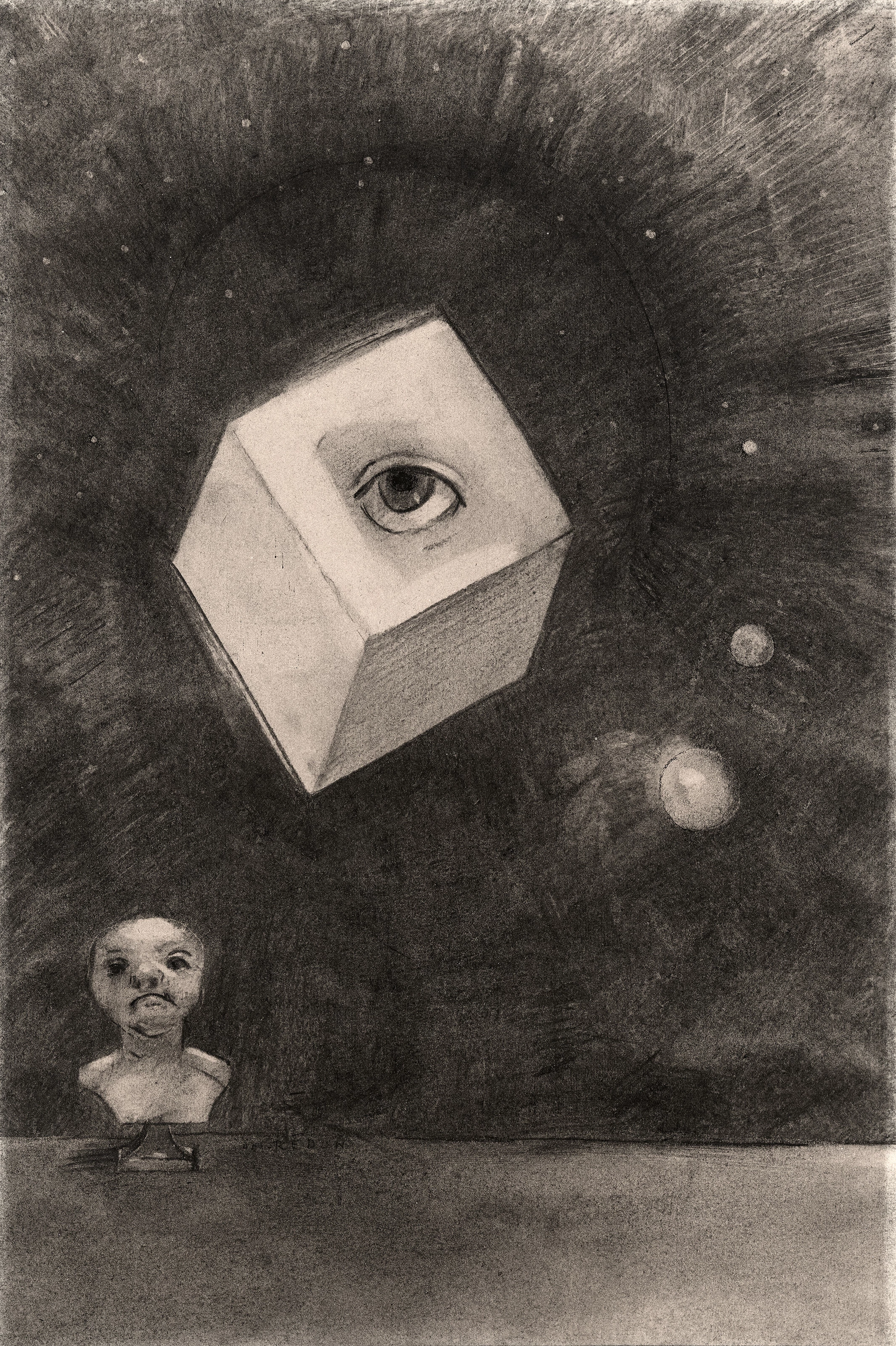

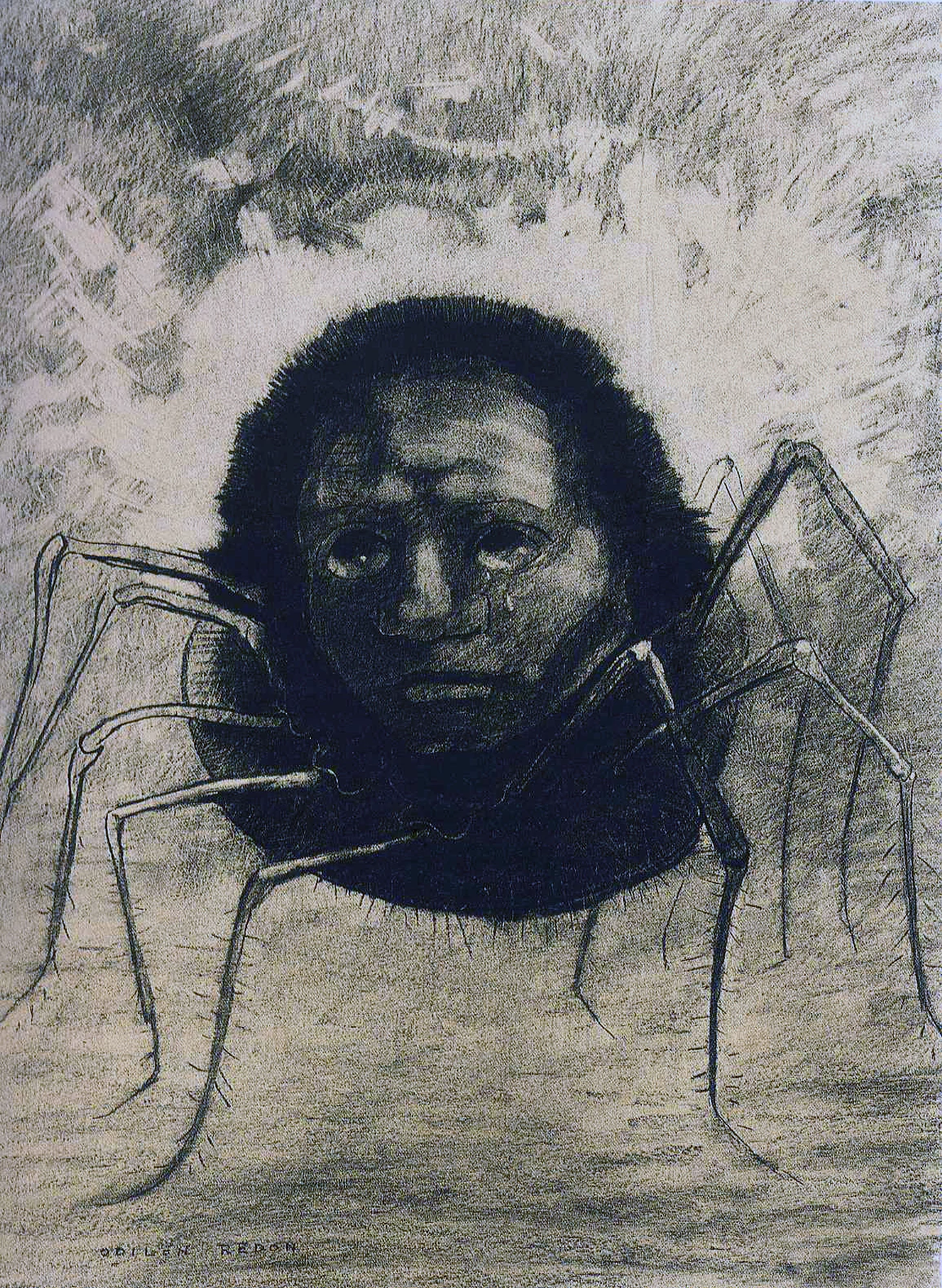

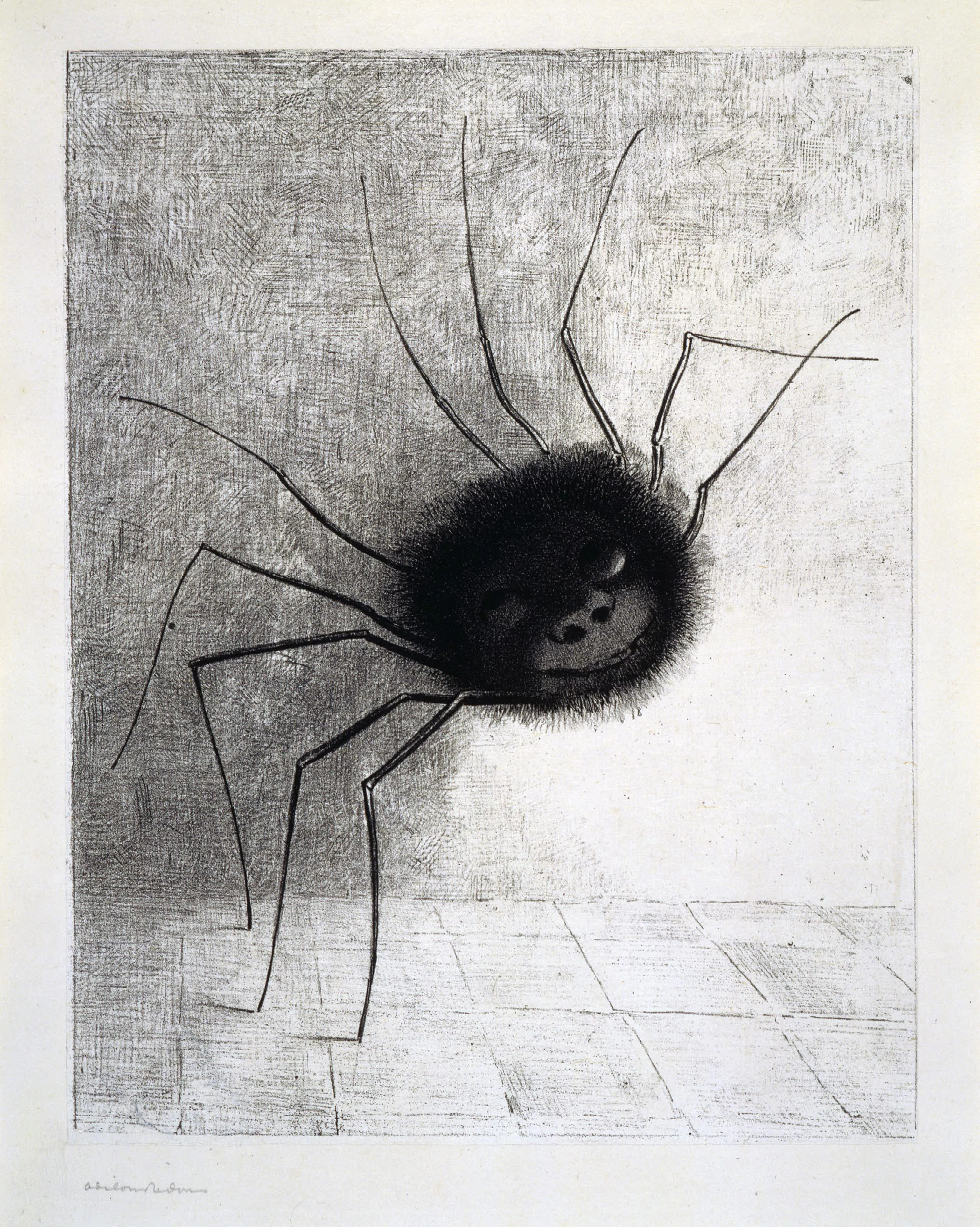

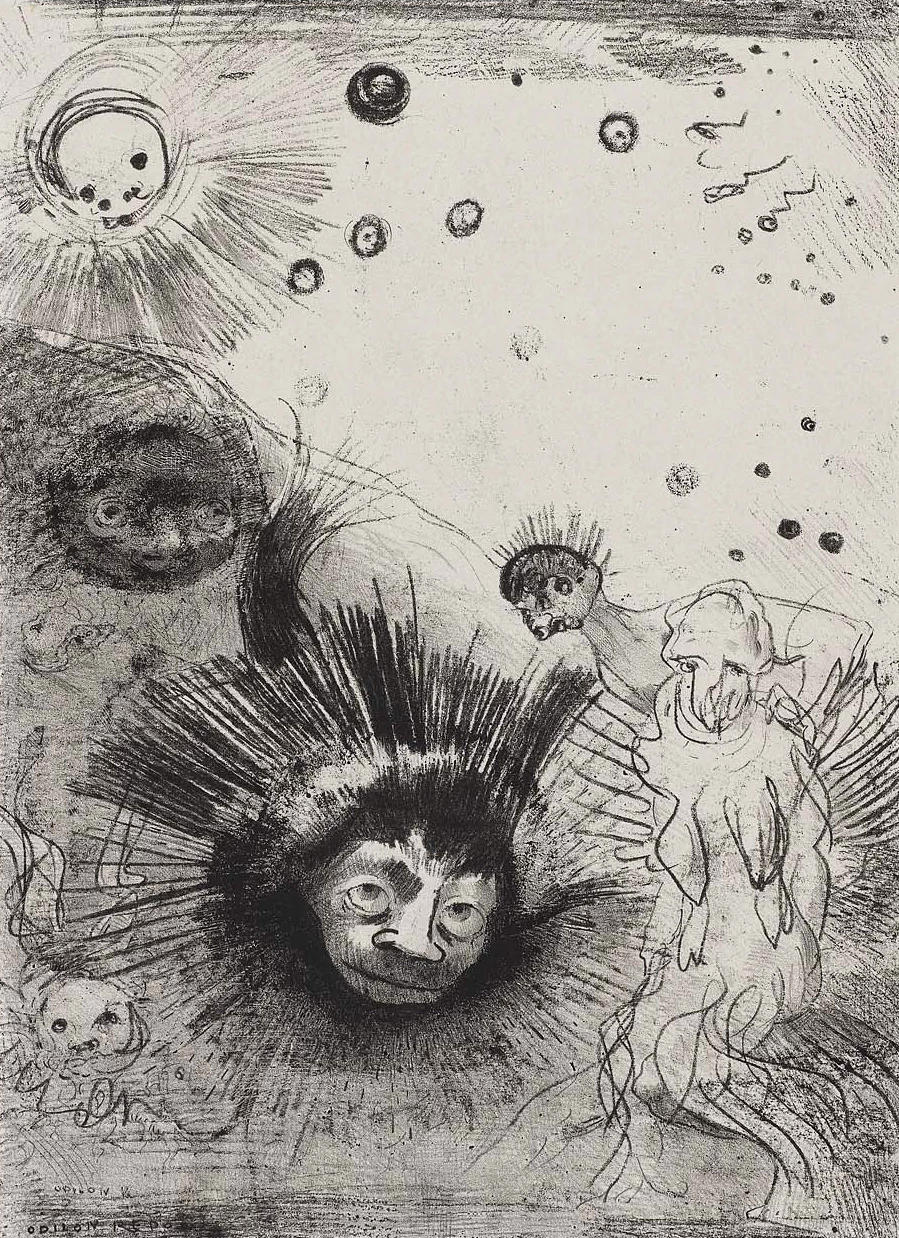

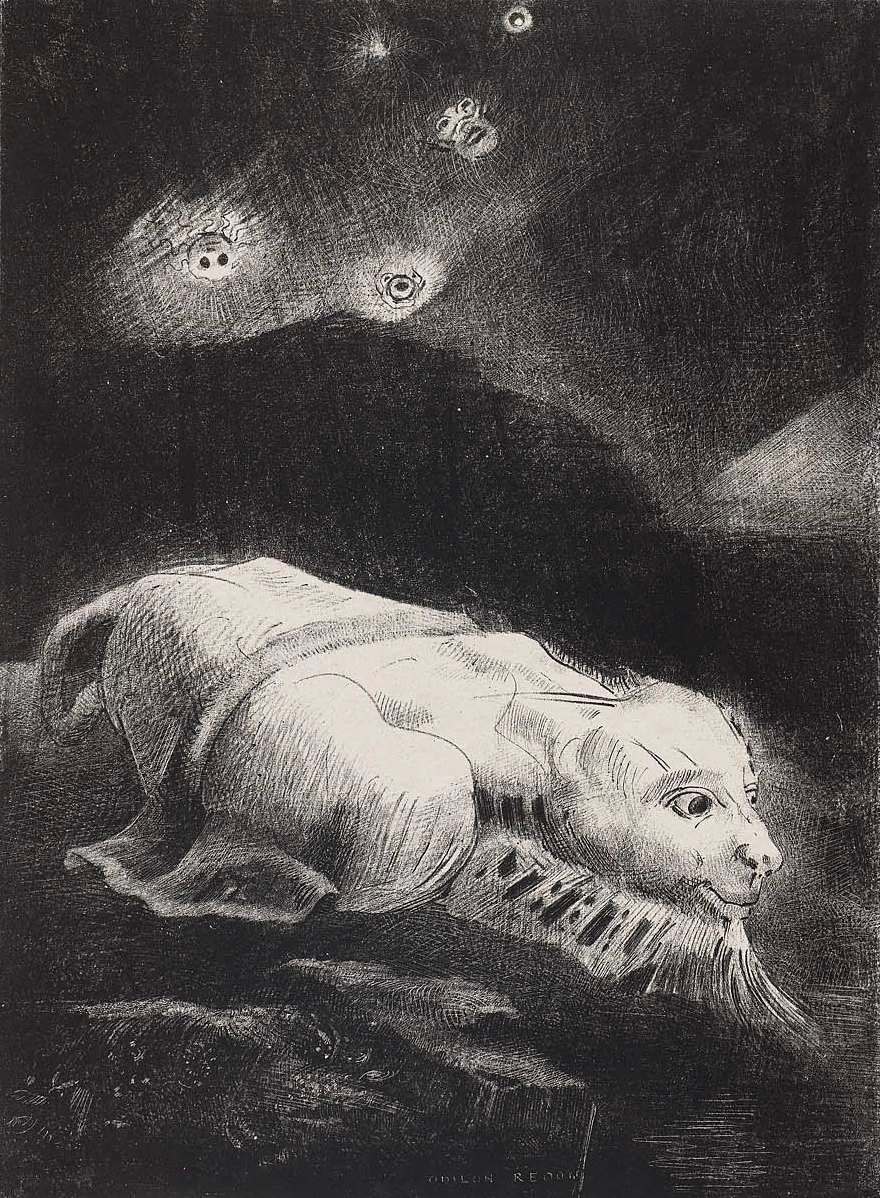

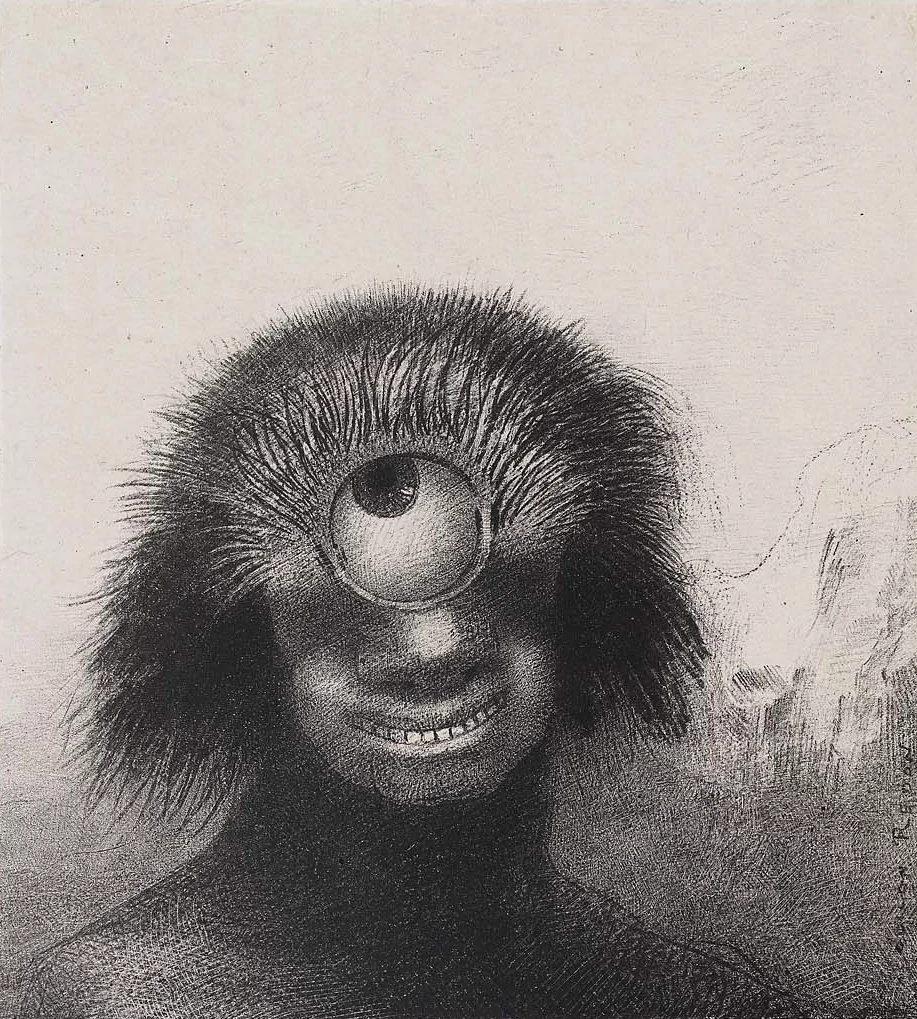

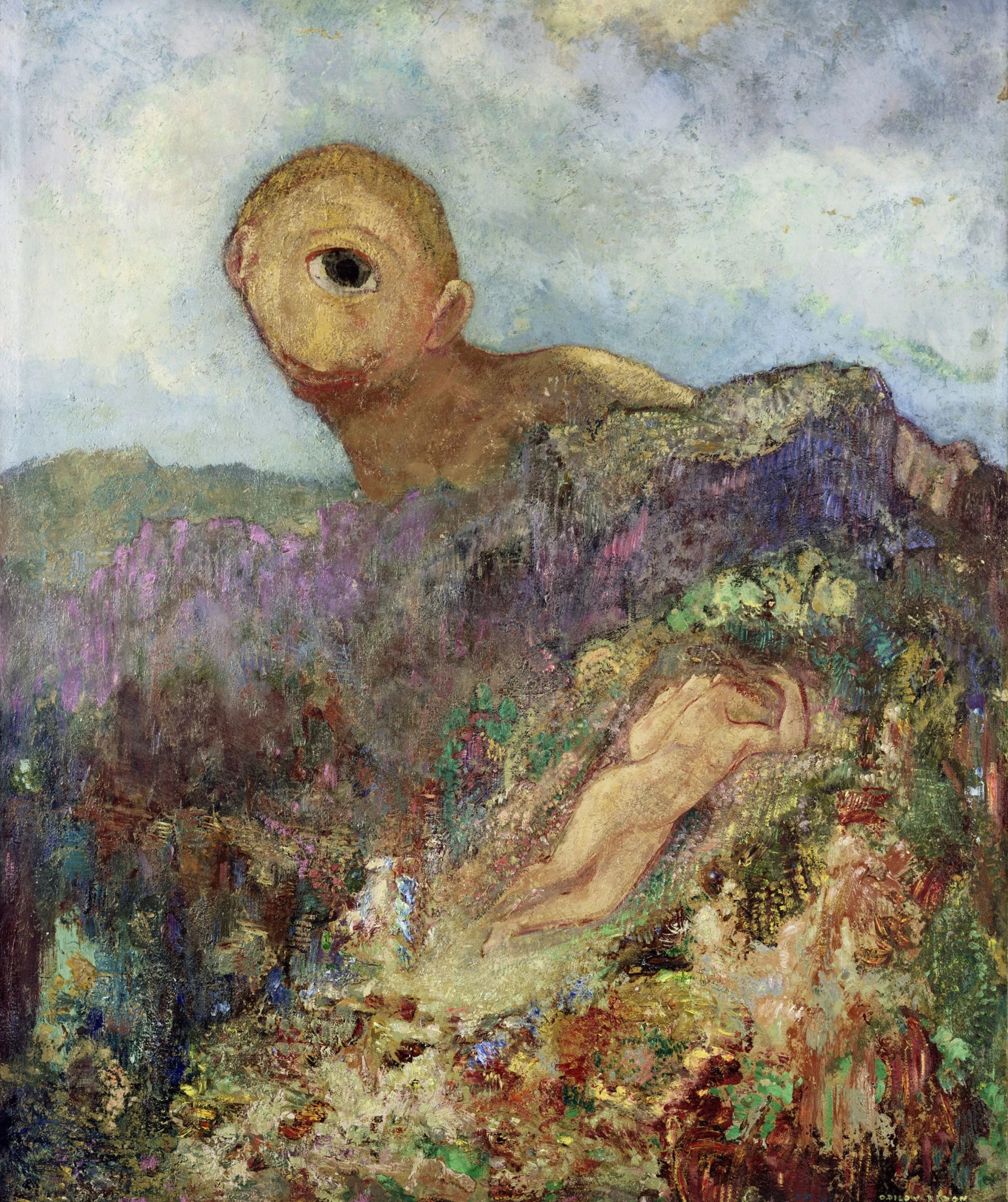

When Odilon Redon was thirty, he put aside his brushes and engraving tools to fight in the Franco-Prussian war. A year later the French lost the bloody conflict, and Redon moved to Paris with a headful of bad dreams. Black visions filled his notebooks after the war. Charcoal drawings of creatures hang in empty space. Winged devils grip giant faces with empty eye sockets. Ears sprout bat wings, and faces emerge from the backs of hairy spiders. Charles Darwin had published The Origin of Species two decades earlier, and the haunting concept of mutated life gripped Europe. Redon’s noirs, his charcoal abominations, illustrated our murky and prehistoric biology.

In 1884, Redon’s work was featured in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ novel À rebours, or Against Nature. It described the decadent perversities of an anti-hero who collected sinister artwork by Redon, Goya, and El Greco, and experimented with weird sex. This association with the macabre grew Redon’s notoriety, and his noirs remain among his most famous works.

“My drawings inspire, and are not to be defined. They place us, as does music, in the ambiguous realm of the undetermined.”

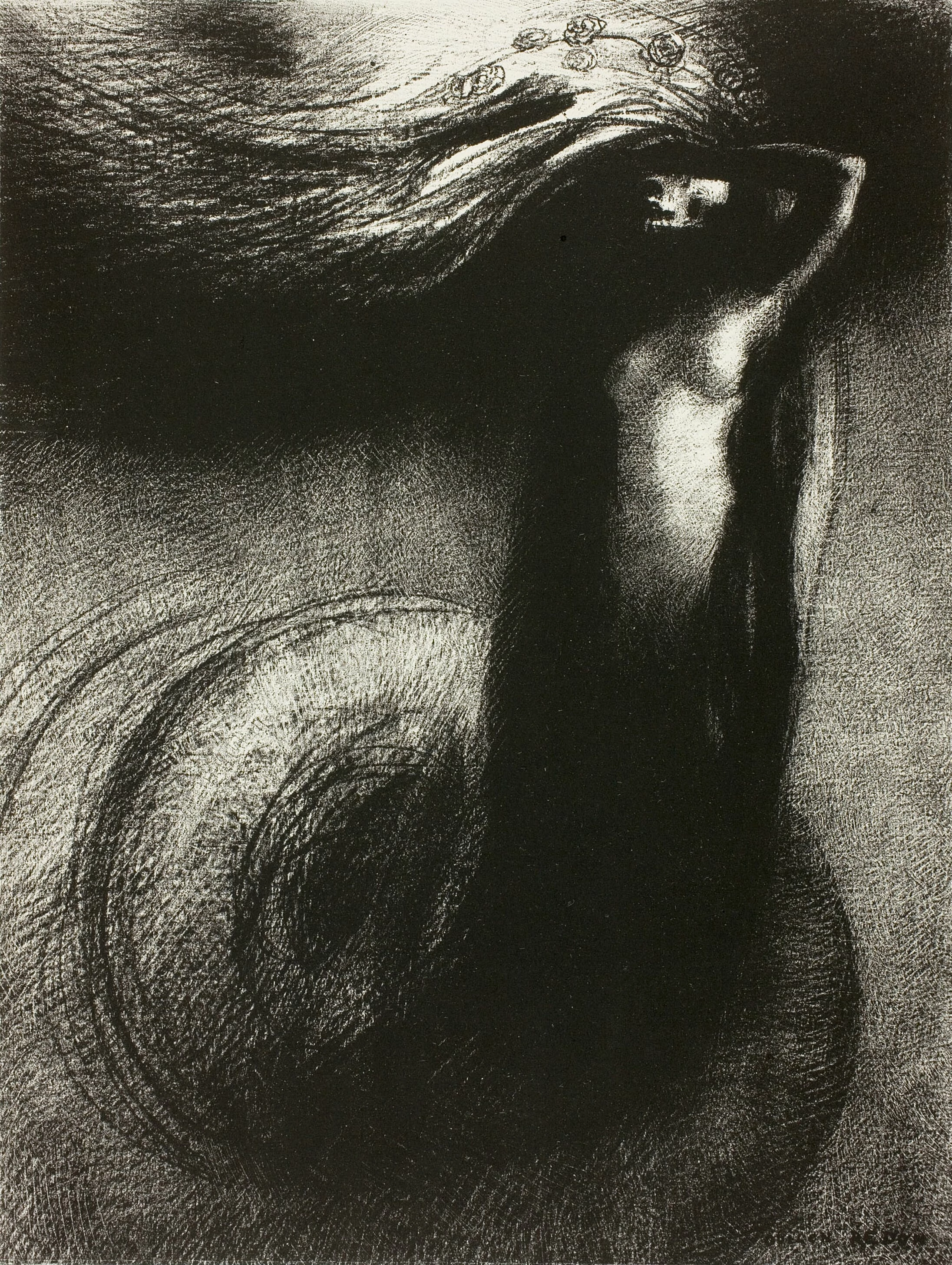

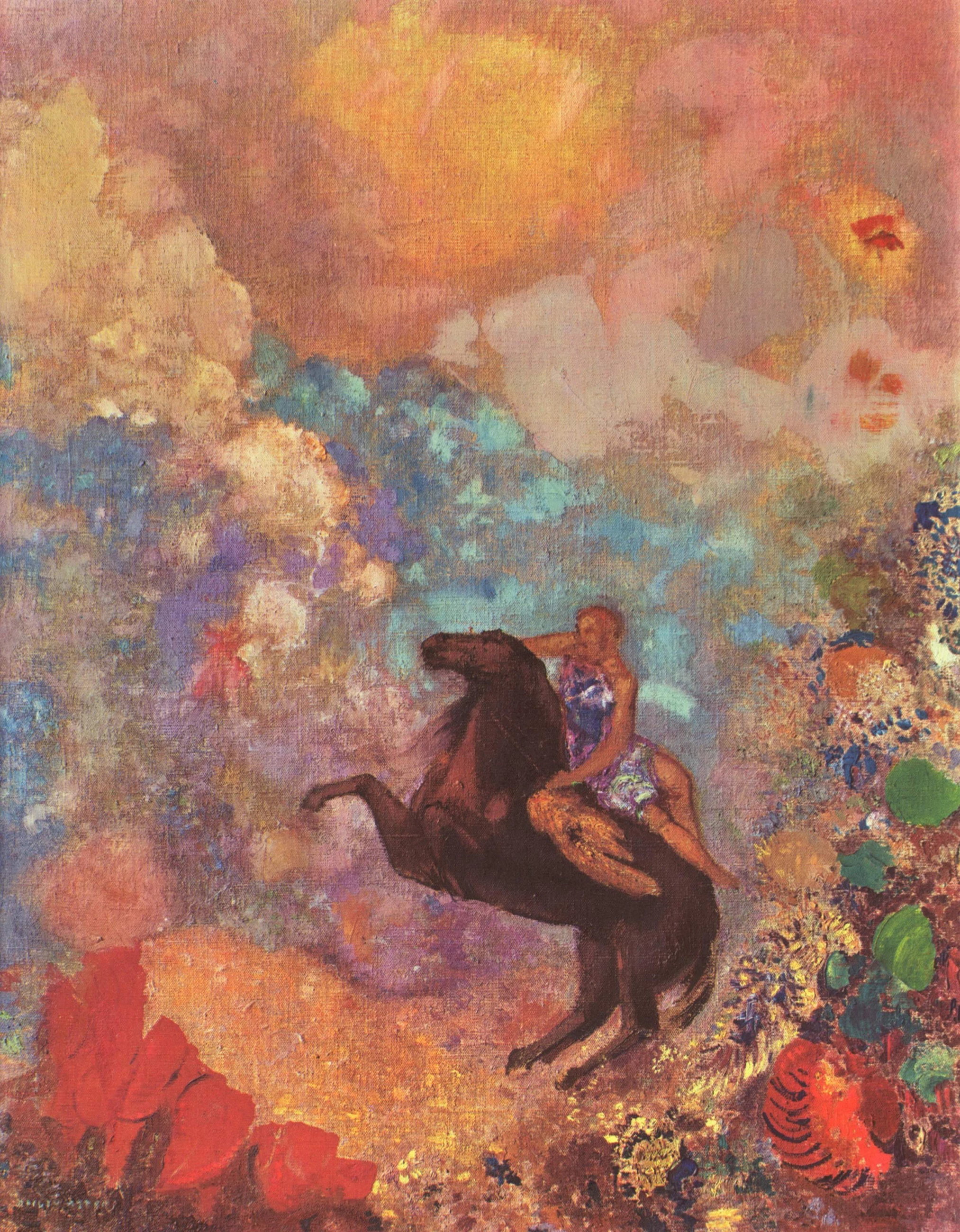

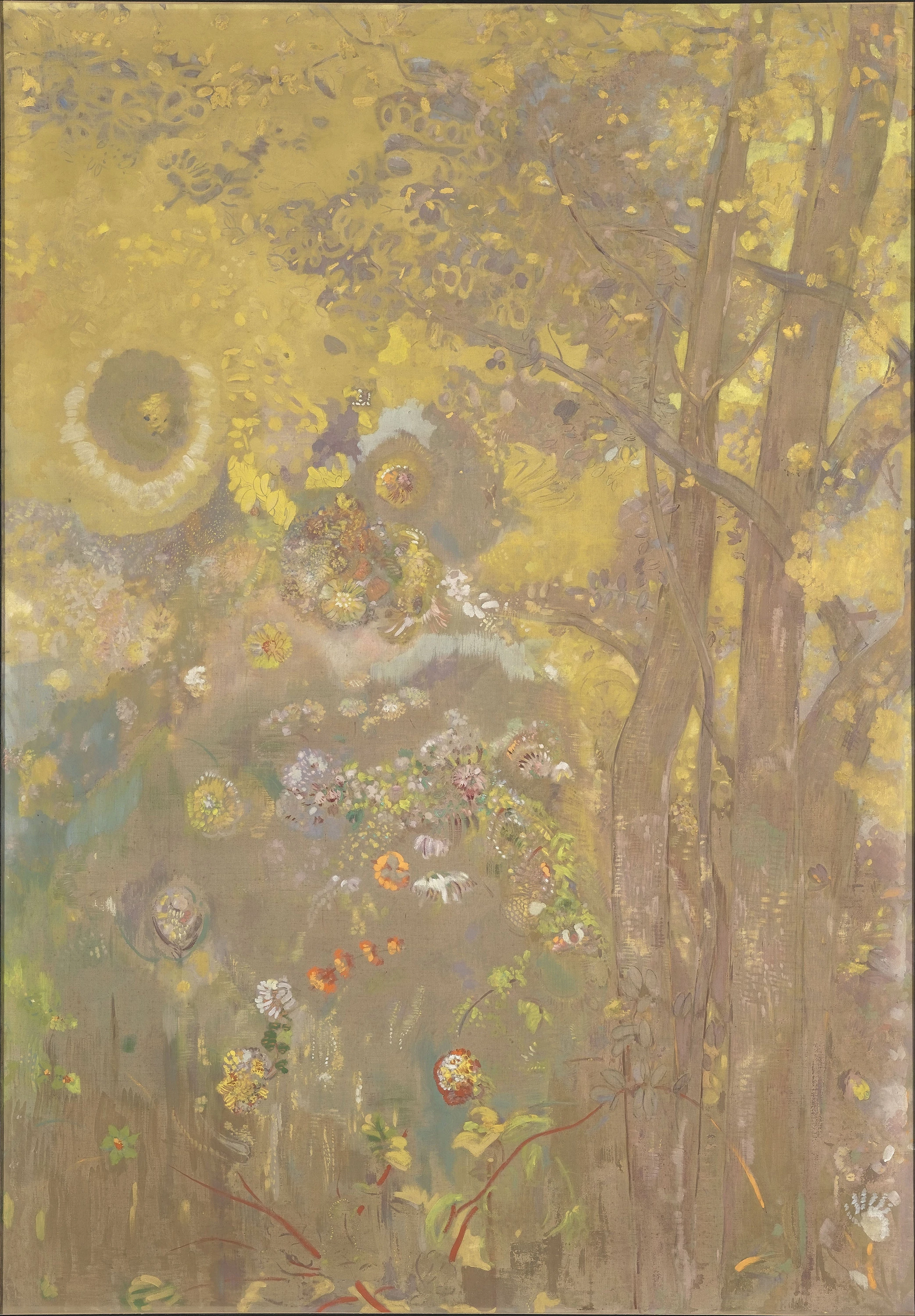

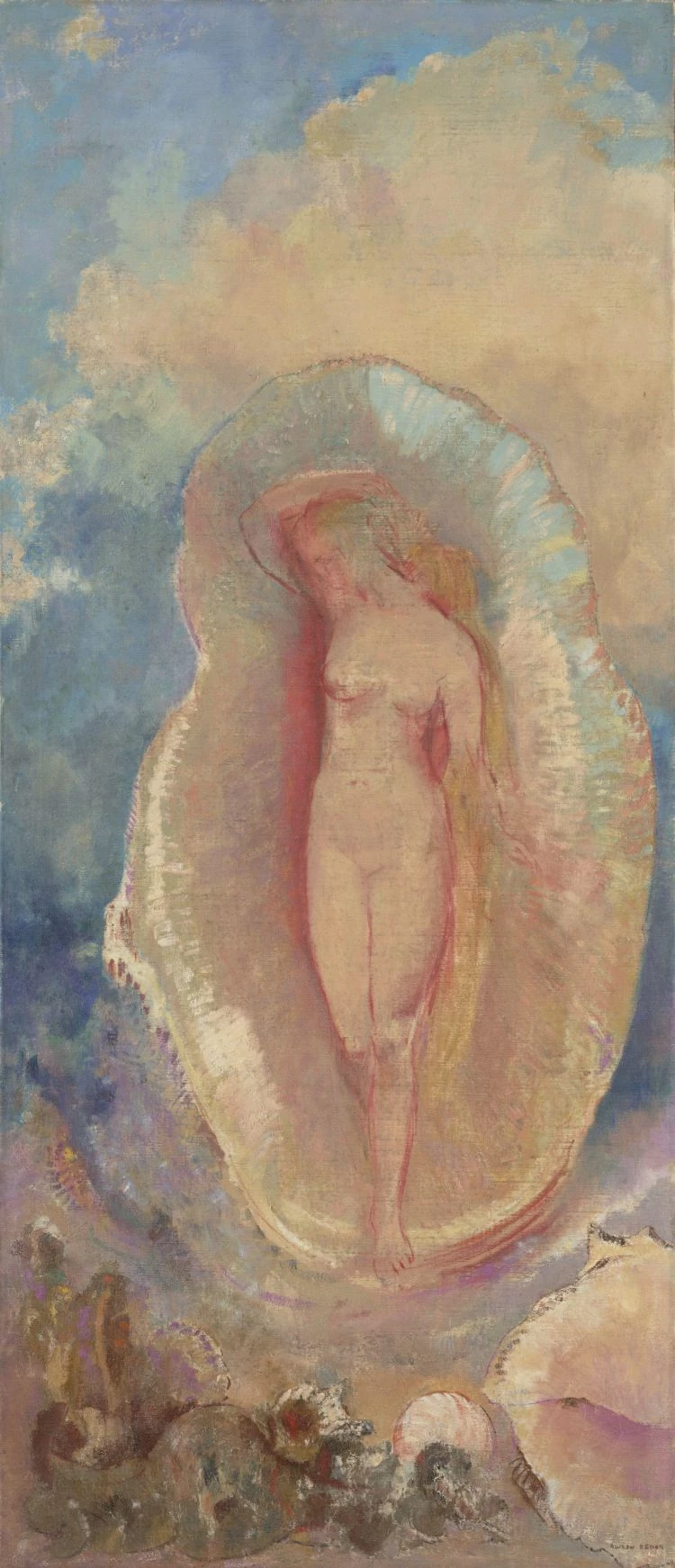

For Redon, science slowly grew to include the spiritual. The German idea of Naturphilosophie, that all living things are interconnected, layered into Buddhist and Hindu philosophy, brought color back into Redon’s world. By the 1890s, Redon worked almost exclusively in pastel, saying it “comforted” him. The spiders and spermatoid eyeballs were replaced by twigs of fresh branches, grasses and flowers. Even his Cyclops appears benevolent. His paintings are dreamscapes still, but they are meditative, quiet—finally at peace.

“The Artist submits from day to day to the fatal rhythm of the impulses of the universal world which encloses him, continual centre of sensations, always pliant, hypnotized by the marvels of nature which he loves, he scrutinizes. His eyes, like his soul, are in perpetual communion with the most fortuitous of phenomena.” — Odilon Redon

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Odilon Redon? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.