James Abbot McNeill Whistler was a privileged child, a moody teen and an utter wastrel as a young man. He would’ve made a good millennial. As a young boy, James was prone to temper tantrums that only drawing could calm. The squeaky wheel gets the grease, and in James’s wealthy family, his preoccupation with drawing was doted on and praised. The son of a railroad engineer, James had the amazing fortune to be educated in art-making in four countries. At age 8, his family moved from Massachusetts to St. Petersburg Russia, where James learned portraiture and life drawing at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts and at fourteen he moved to London, where he learned watercolors and etching from the engraver Sir Francis Haden.

On his return to the United States, young James was granted admittance to the West Point military academy on the strength of his family name. He immediately proved himself a sloppy dresser, with a dismissive attitude and poor grades. But his talent was undeniable, and after his expulsion from the program, James was hired as a draftsman and map-maker for the U.S. military—a job he promptly lost through tardiness and a habit of drawing sea serpents in the margins of the maps. At 21, James said goodbye to America forever, and moved to Paris to paint, drink, smoke cigarettes, and revel in bohemian drama.

“Besides being a Master of the Brush, Pencil, and Etching Needle, and pretty handy with his Pen, Mr Whistler was a Master of the great art of attracting attention.” — Don C. Seitz

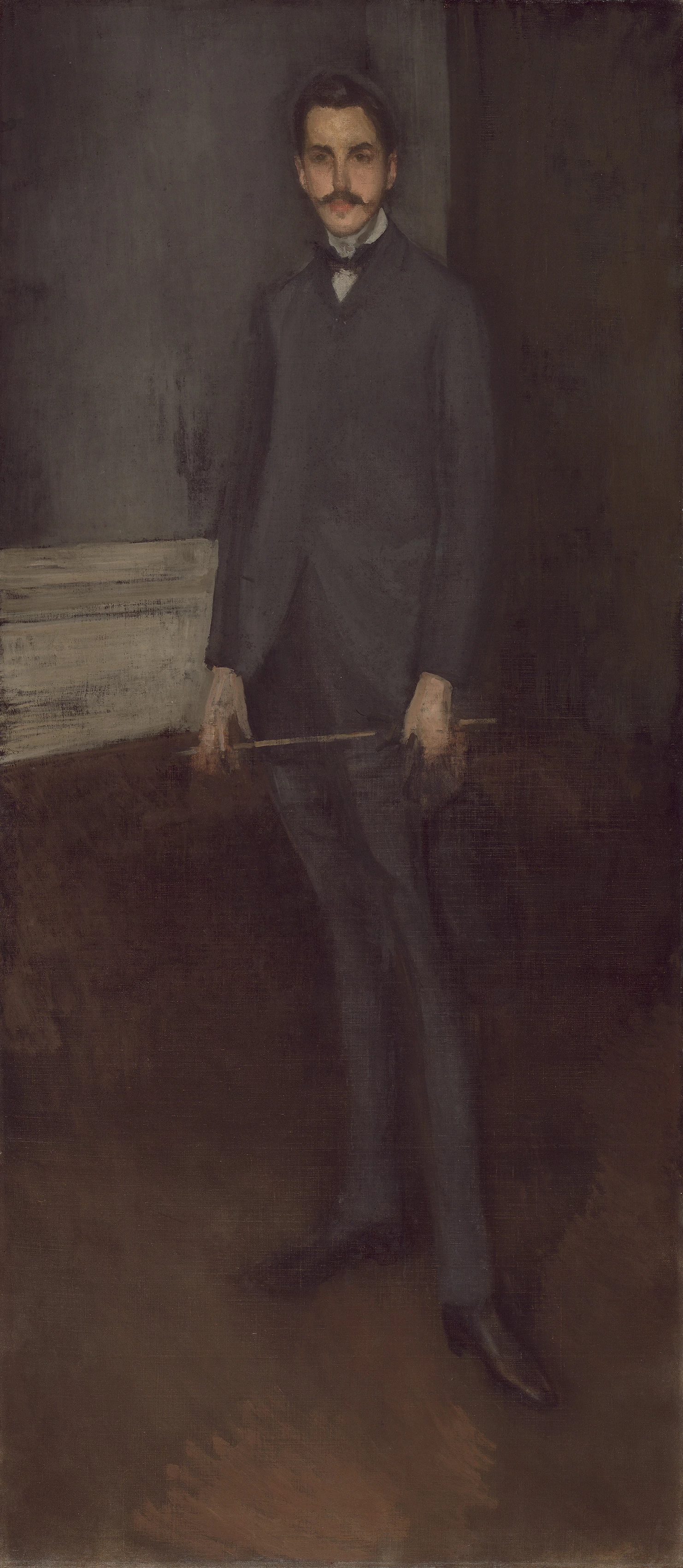

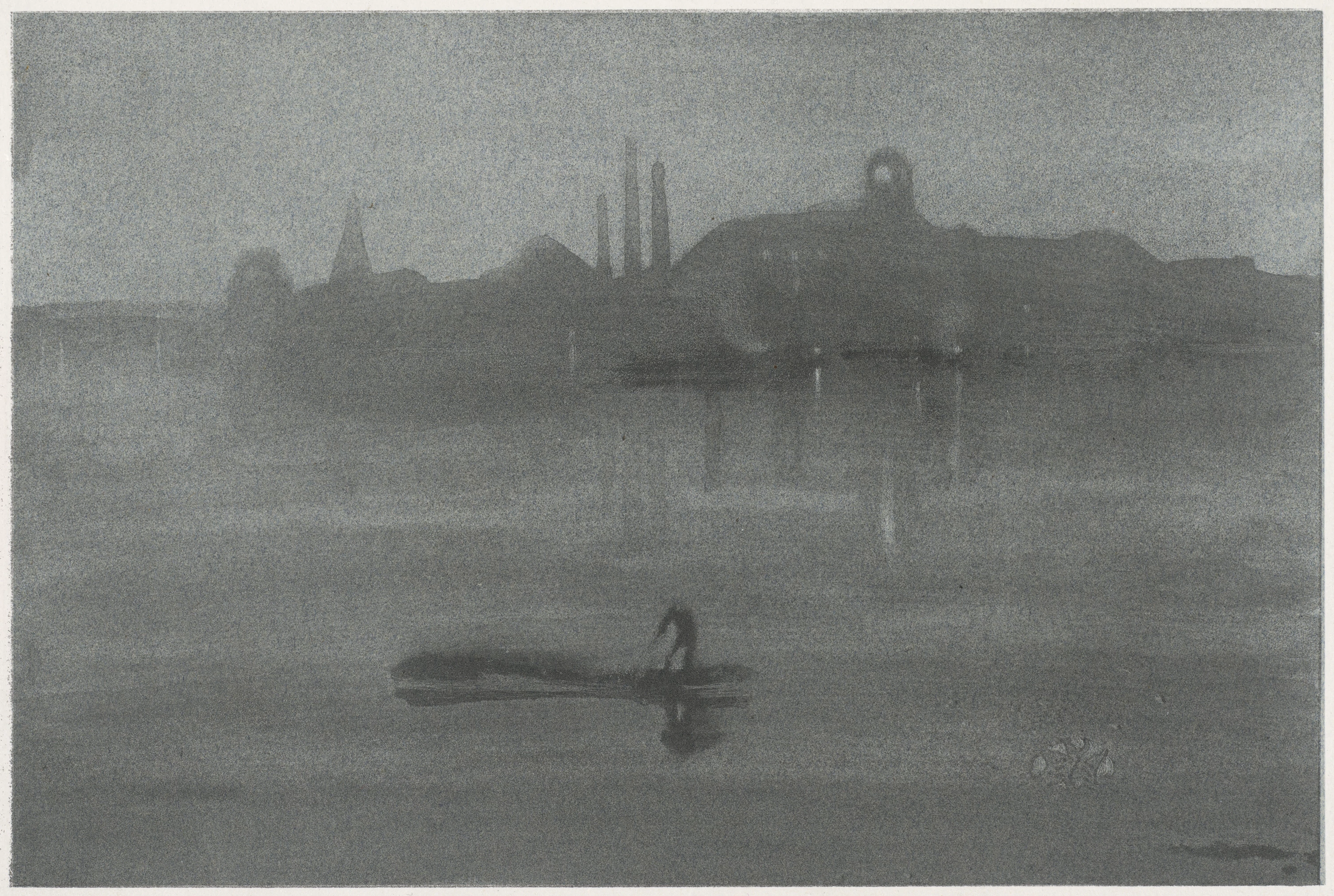

Whistler’s talent is undeniable. He mastered oils, engraving, lithography and even early photography—proof his dedication to his work. Arthur Eddy, who sat for a portrait by Whistler described his authoritative technique, “He worked with great rapidity and long hours…it was as if the portrait were hidden within the canvas and the master by passing his wands day after day over the surface evoked the image.” And Whistler’s theory of art was also demanding. Influenced by a love of music, he pioneered the ‘tonalist’ practice of flooding images with unifying colors, creating compositions that oozed atmosphere and influenced the developing Impressionist movement.

But Whistler didn’t just know how to make art—he knew how to posture. He was a short man, thin, unhealthy, and continually in debt, but Whistler’s wit was as sharp as his engraving needles. Every show of his work was followed by a battle in the press. Critics loved to hate him, and Whistler countered each vindictive review with his bitter response. Over the course of his career, Whistler created and destroyed a friendship with Oscar Wilde, sued the famous art critic John Ruskin for libel, and alienated Gustave Courbet by hooking up with their mutual muse Joanna Hiffernan.

While Whistler’s art was sensitive and stunning, his career a parade of vitriol and drama, which came to a head in 1890 with the publication of his first book. The Gentle Art of Making Enemies is a strange volume. It collects Whistler’s lifetime of banter, arguments, and criticism into a single noisy pile. The majority of the volume are poor reviews of his own art. Critics misunderstanding and reviling Whistler’s work. His brilliant and barbed letters to Wilde are there, and the full transcript of his legal battle with Ruskin.

Whistler’s signature was not his name, it was a sketch of a butterfly with a barbed tail. He knew what he was. A spoiled brat, a masterful artist and a social kick-boxer. Love him or hate him, Whistler reminds us: don’t dismiss the haters, profit from them.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about James McNeill Whistler? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

Listen! There never was an artistic period. There never was an Art-loving nation. In the beginning, man went forth each day—all that they might gain and live, or lose and die.

Art should be independent of all clap-trap—should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like.