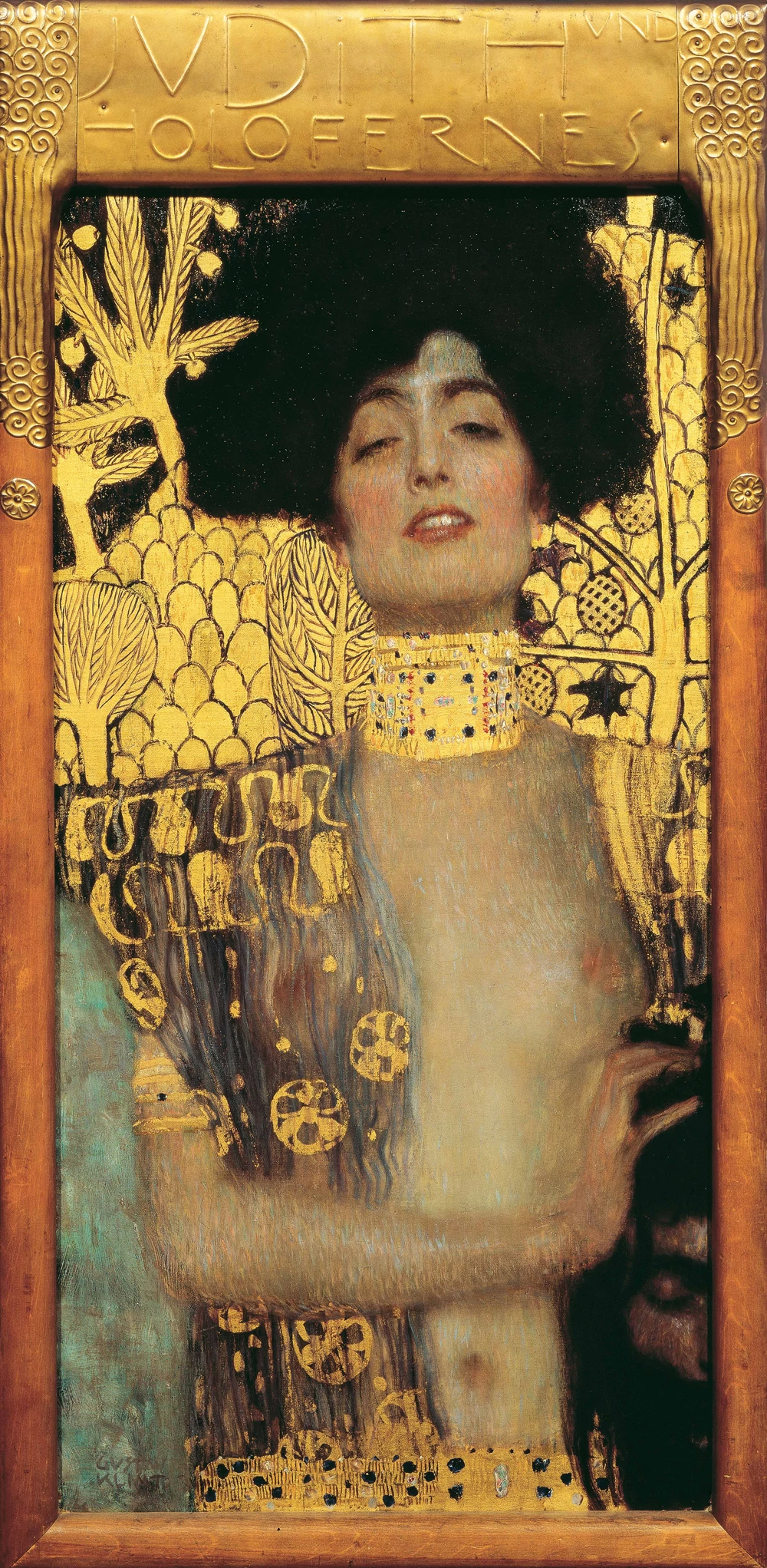

Ok let’s be real, Gustav Klimt’s Judith and the Head of Holofernes is a weird treatment of its subject matter. The beheading of the unstoppable Assyrian general Holofernes by the beautiful, pious widow Judith is a violent exclamation point in the Christian Apocrypha. It’s the bloody, extremely satisfying story of a fiercely intelligent woman single-handedly upending a patriarchal power, and an extremely popular theme in painting from the Renaissance until, honestly, today. But take a look at some of the many, many artworks of the famed beheading and you’ll notice that while Judith is often depicted as strong, determined, even calm—you'd rarely call her vampy.

In the gold-leafed hands of Mr. Klimt, Judith’s bloody sword disappears along with her shirt, and the general’s head is pushed mostly out of frame. What’s left is a languid, sensual version of the once-chaste widow. Her eyes are heavily lidded, lips parted, neck tightly ringed in gold—as inviting as Holofernes found her in his last moments. Even the way she paws at the dead general’s hair is upsettingly sexy.

A couple of interesting details: if you recognize this face, it’s no accident. Despite some slight changes to her features, the model for Judith was Klimt’s longtime friend and lover Adele Bloch-Bauer—which may help account for the boldly erotic overtones of the piece. Anecdotally, Judith’s strange crescent hair-do also appears in Klimt’s portraits of both Emilie Flöge and Marie Henneberg—was a popular look at the turn of the century? And finally the gilded hills and fig trees behind Judith look to be styled after relief sculptures from the palace of the Assyrian king Sennacherib in ancient Nineveh, a nice touch, if you ask me.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Judith and the Head of Holofernes? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.