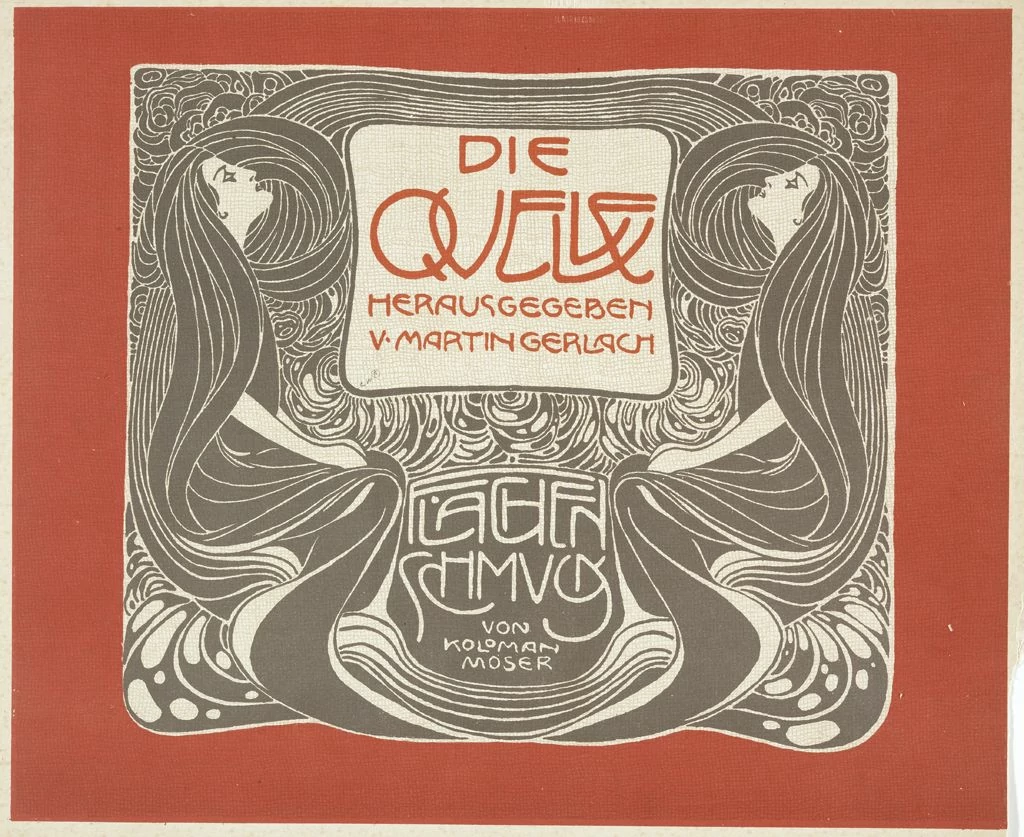

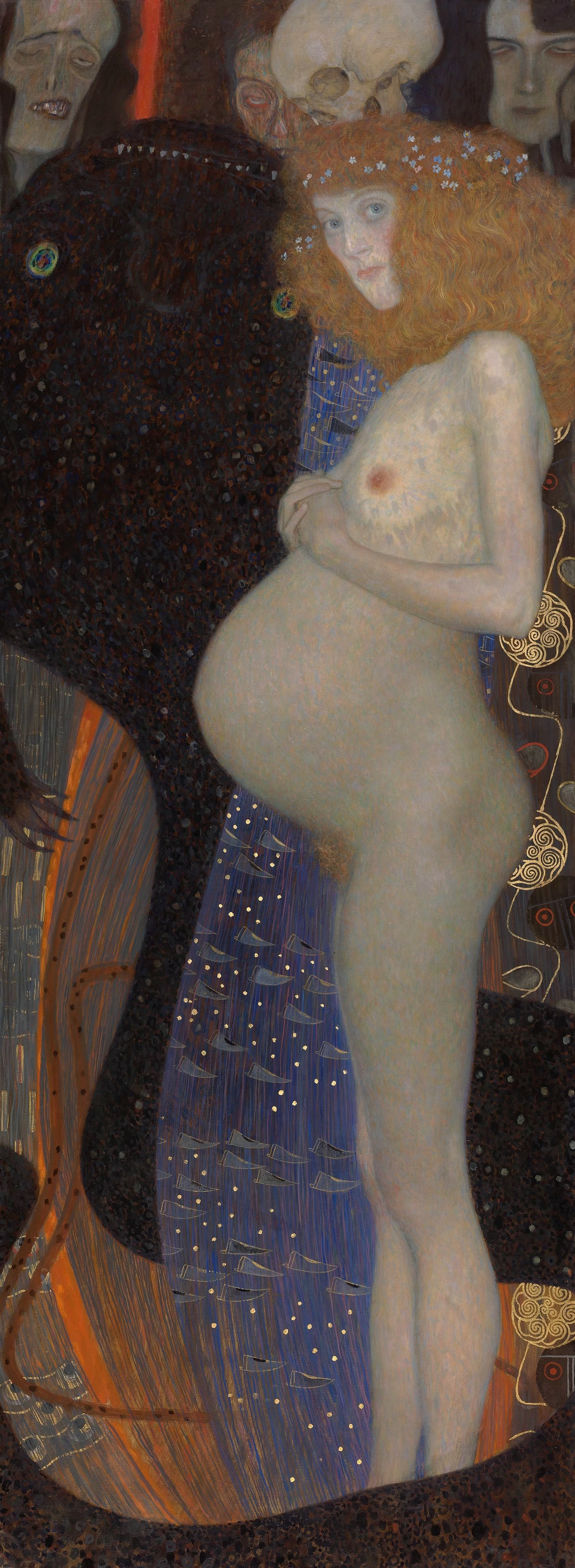

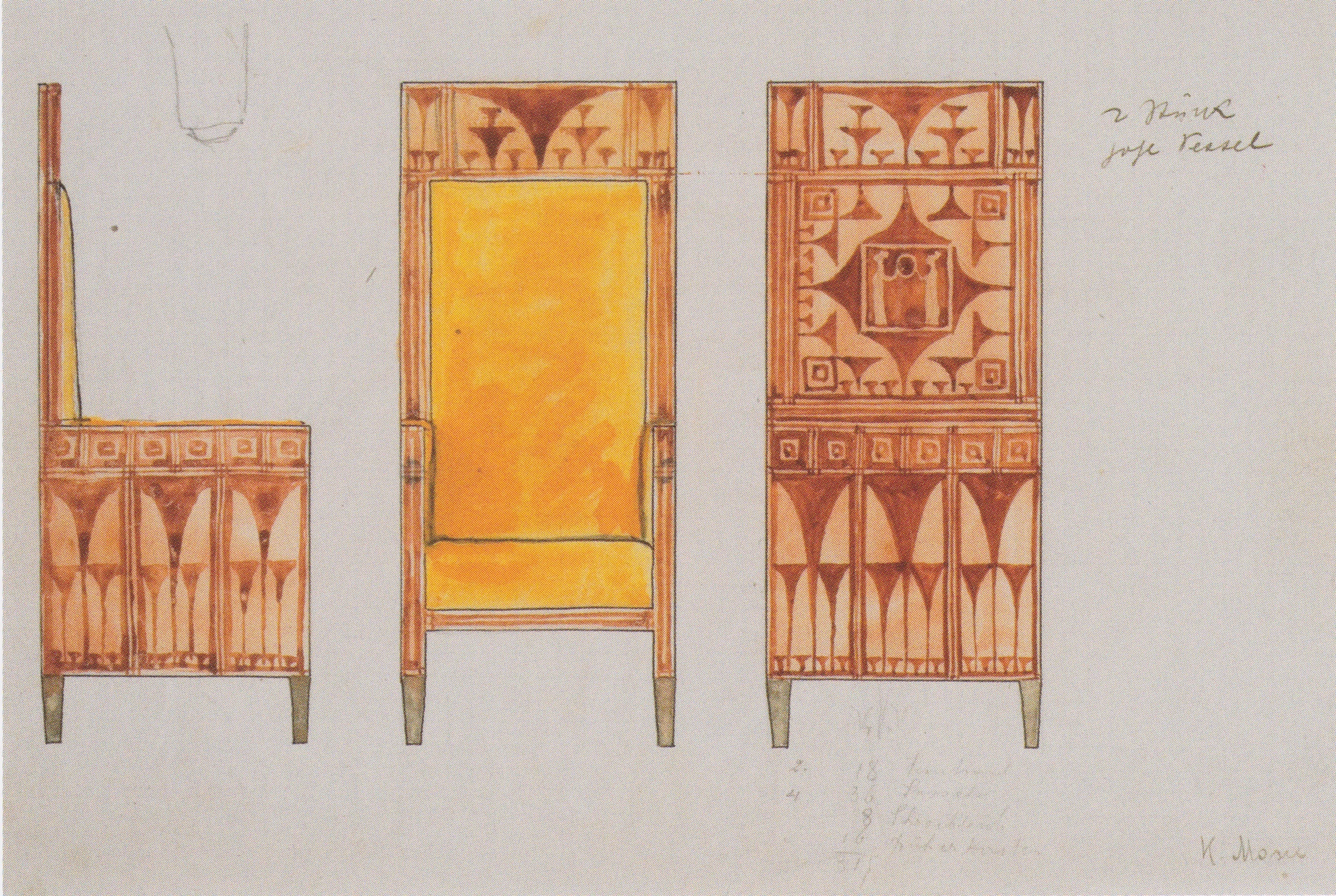

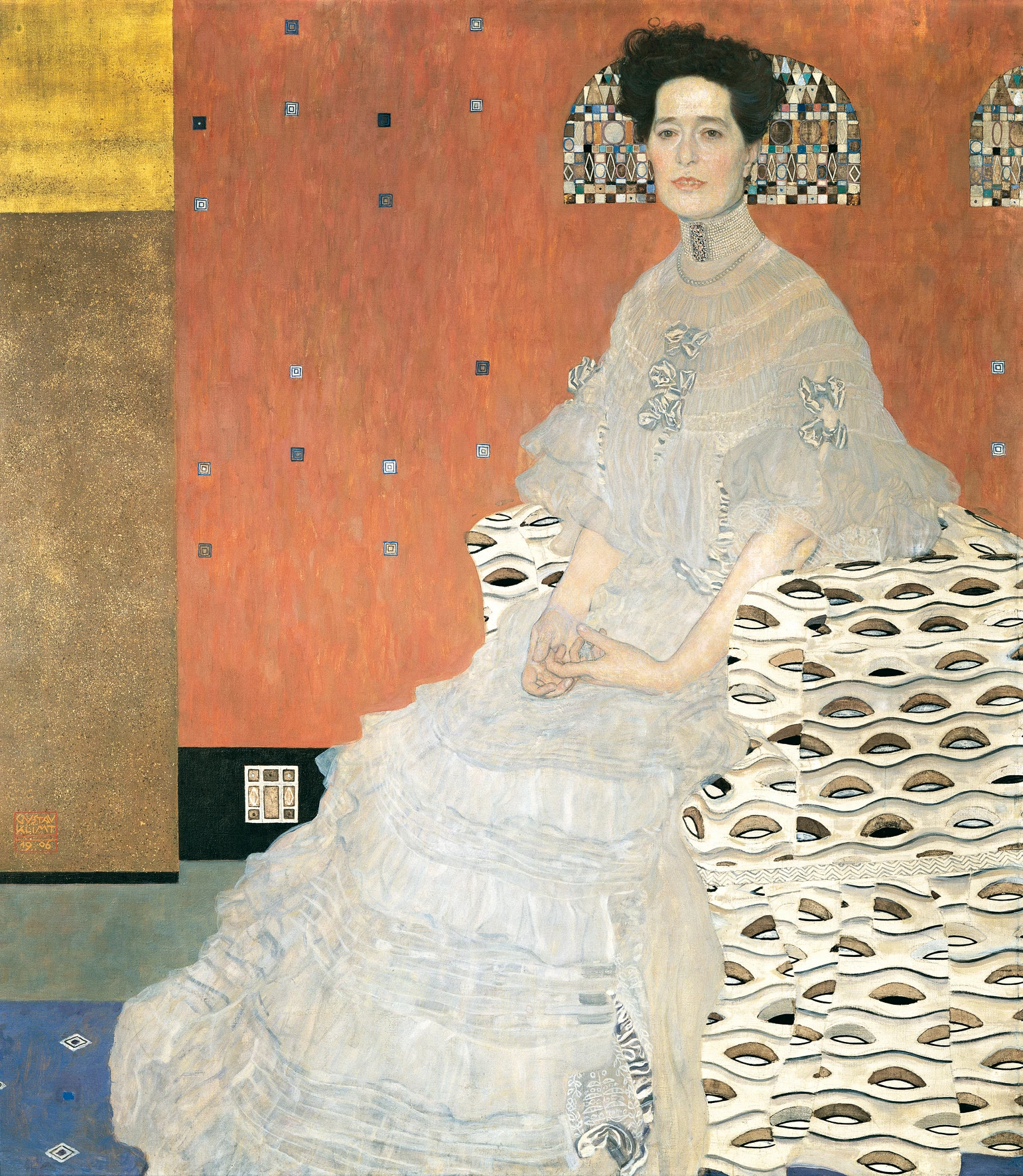

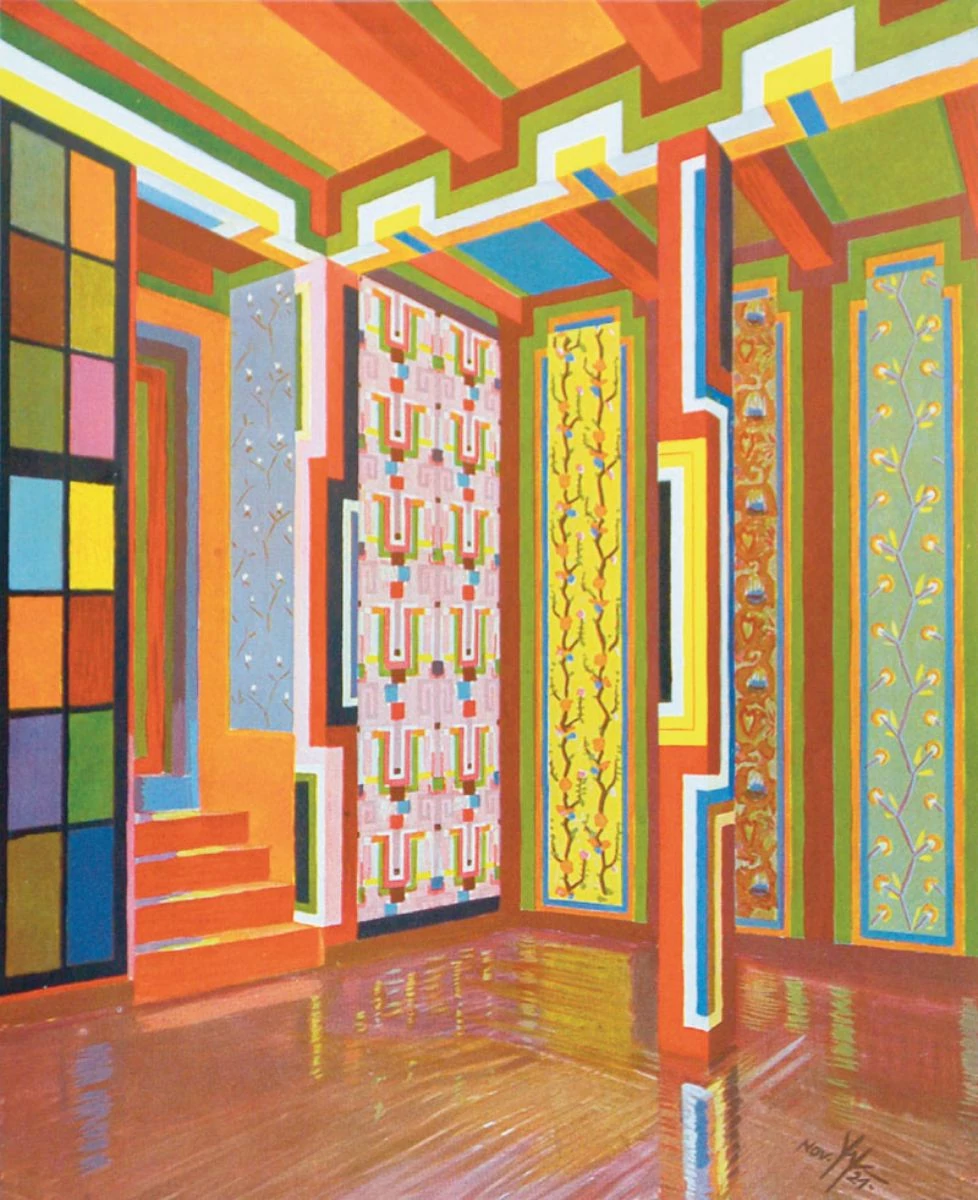

Art Nouveau appeared at the turn of the 20th century all at once, everywhere. A style defined by sinewy, organic lines and an overtly decorative flair, it was called Modern Style in Britain, Style Nouille in Belgium, Wiener Jugendstil in Germany, and Tiffany Style in the United States. So what on earth was it, and how did it spread so fast?

The decades before 1900 were a perfect storm of aesthetic developments and cultural evolution, leading to a global Art Nouveau takeover. We don’t usually go for bullet points at Obelisk, but there’s a lot to cover. Here are just a few of the influences:

So Art Nouveau was the complex child of illustrators, artists, Japanism, industrialization and enterprising magazine salesmen. But it exploded at the Exposition Universelle, the World’s Fair held in Paris in 1900. Nearly 50 million people flooded into the city to see modern marvels like the escalator, diesel engines, and Matryoshka dolls. But the real highlight of the Exposition was the ‘new art'—which was built into the event itself. The grand Porte Monumentale entrance and many of the pavilions were designed in the organic, ‘whiplash’ style, and the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, a decorative arts organization, showcased purchasable art nouveau furniture and housewares, sending people all over the world back to their homes with a piece of the movement.

Art Nouveau grew quickly, and faded from popularity incredibly fast. By 1910, the style had evolved from organic floral motifs into geometric angles—morphing into the ubiquitous 1920s aesthetic Art Deco.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Art Nouveau? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

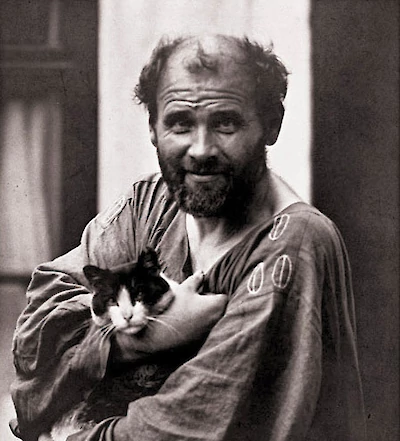

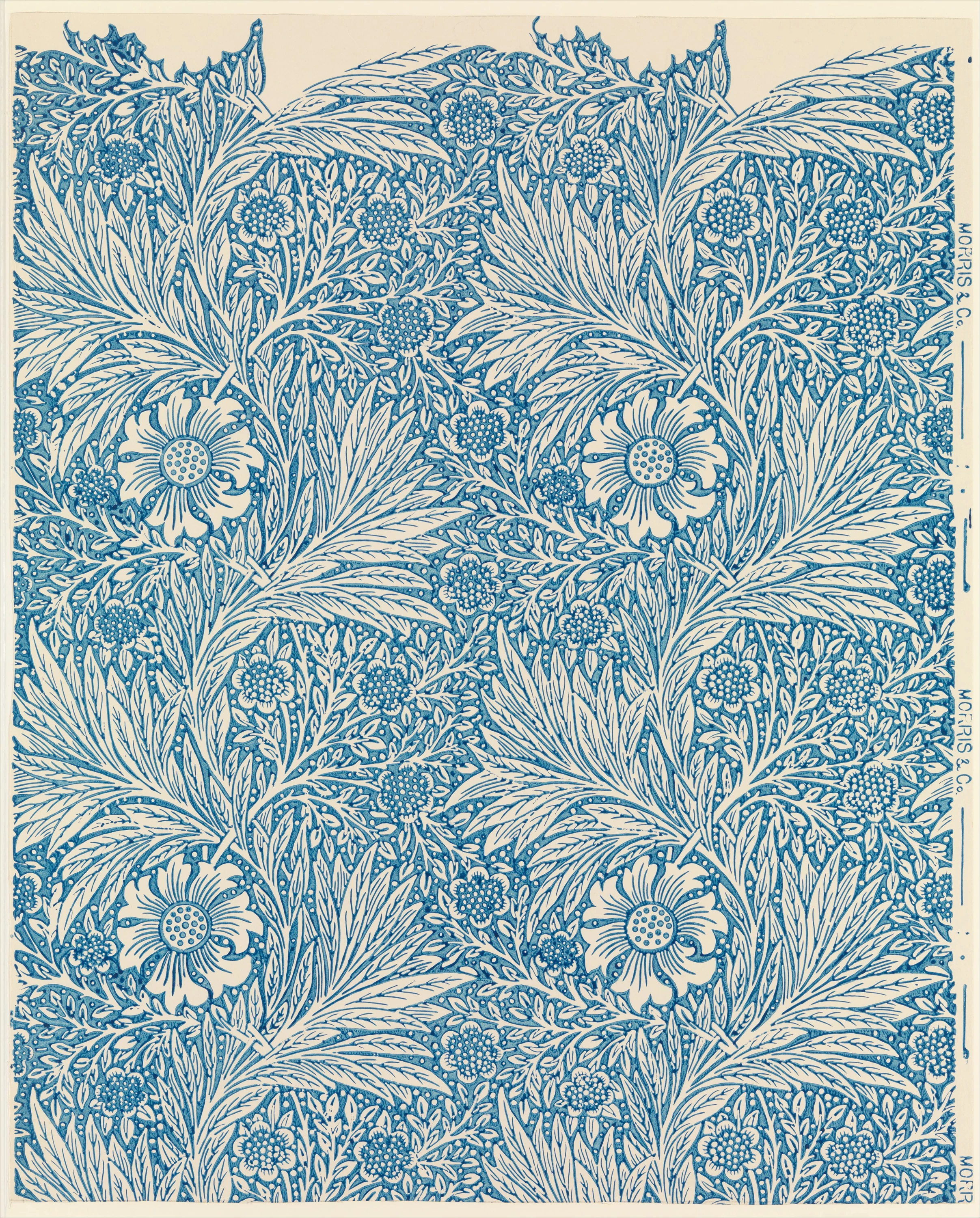

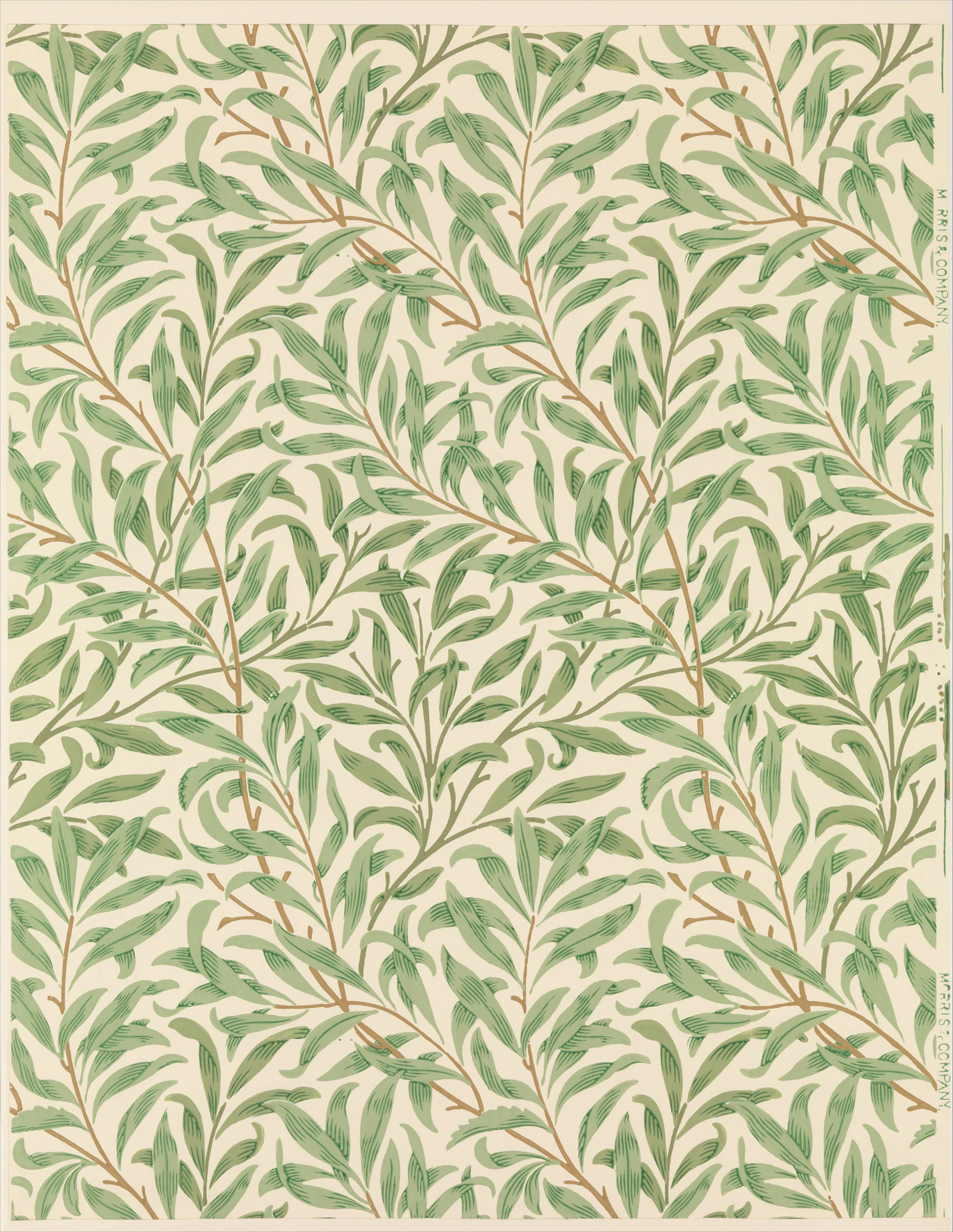

Can you run a socialist company in a capitalist economy?

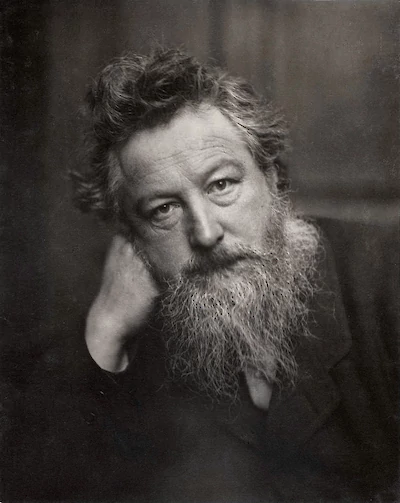

1834 – 1896

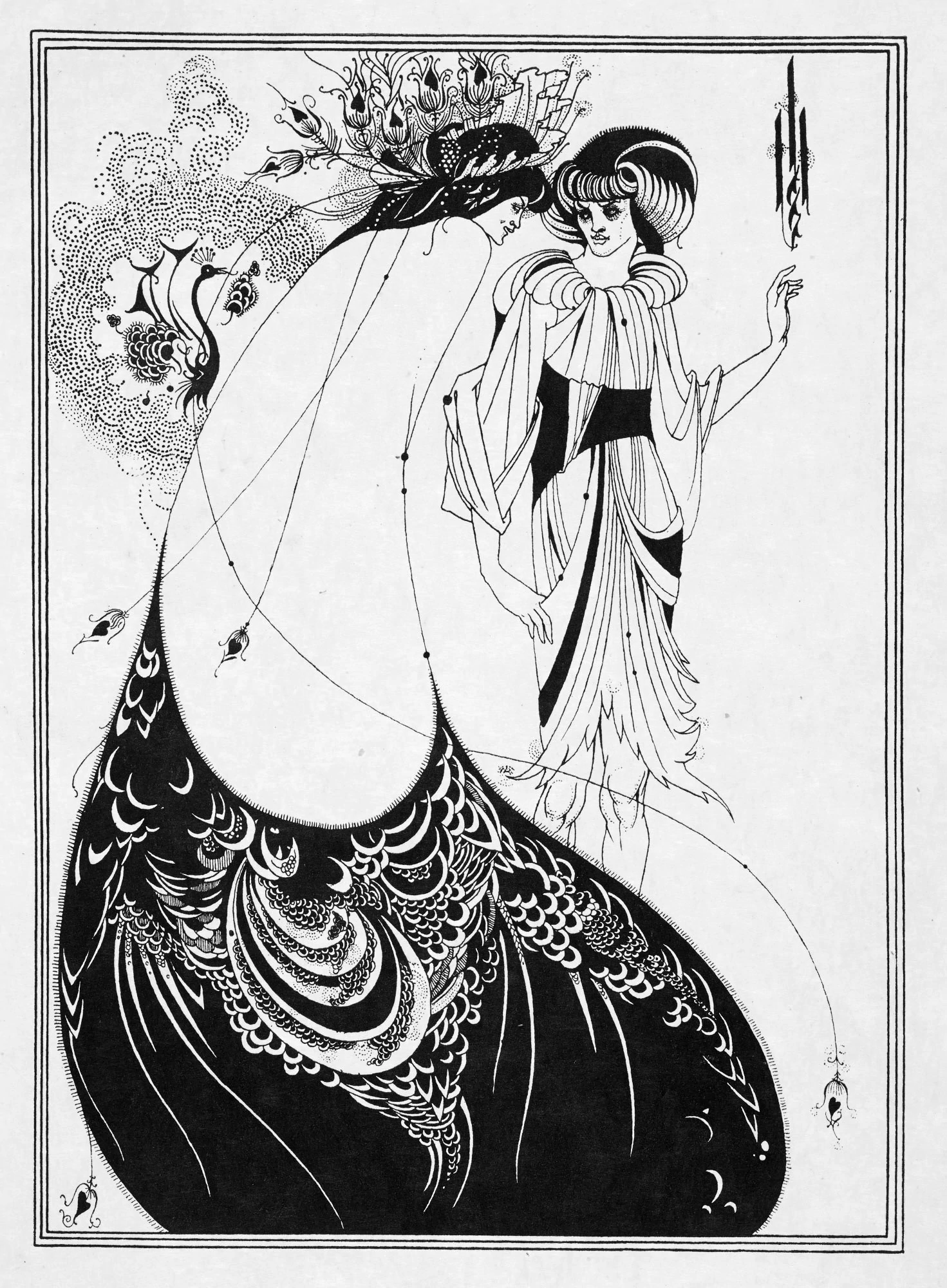

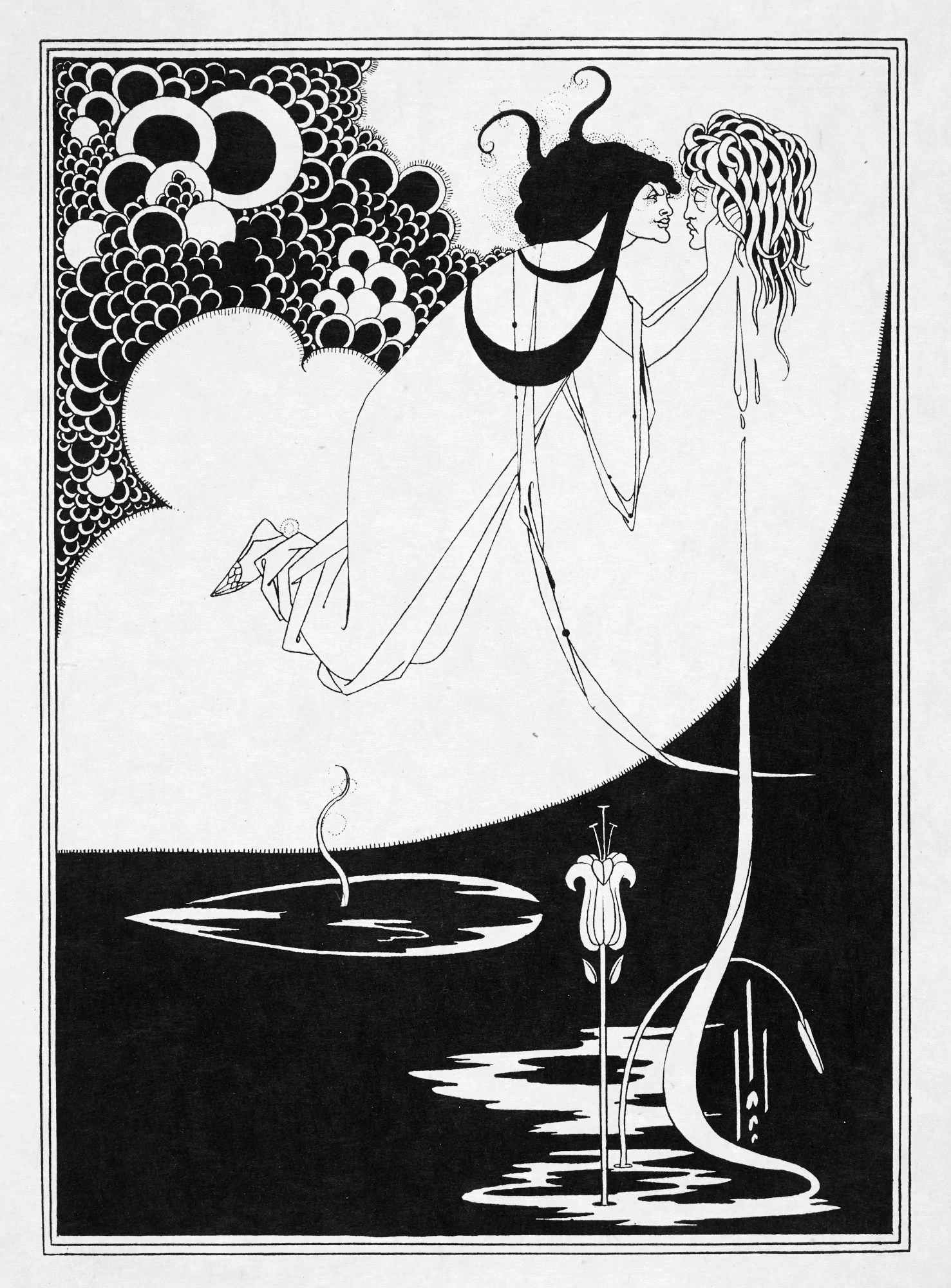

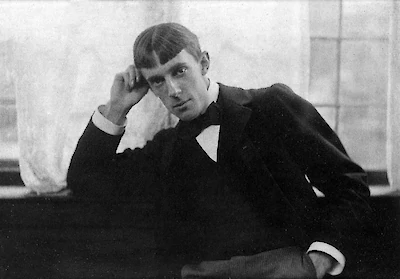

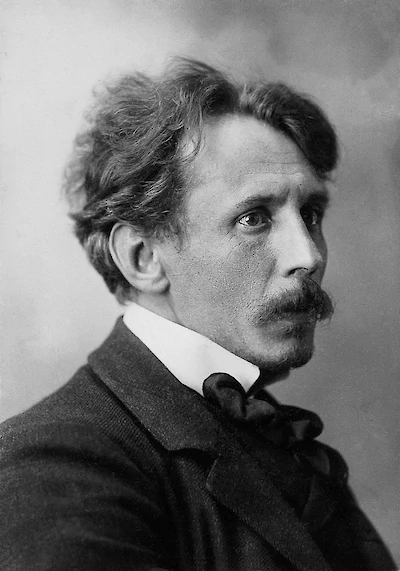

"If I am not grotesque I am nothing"

1872 – 1898

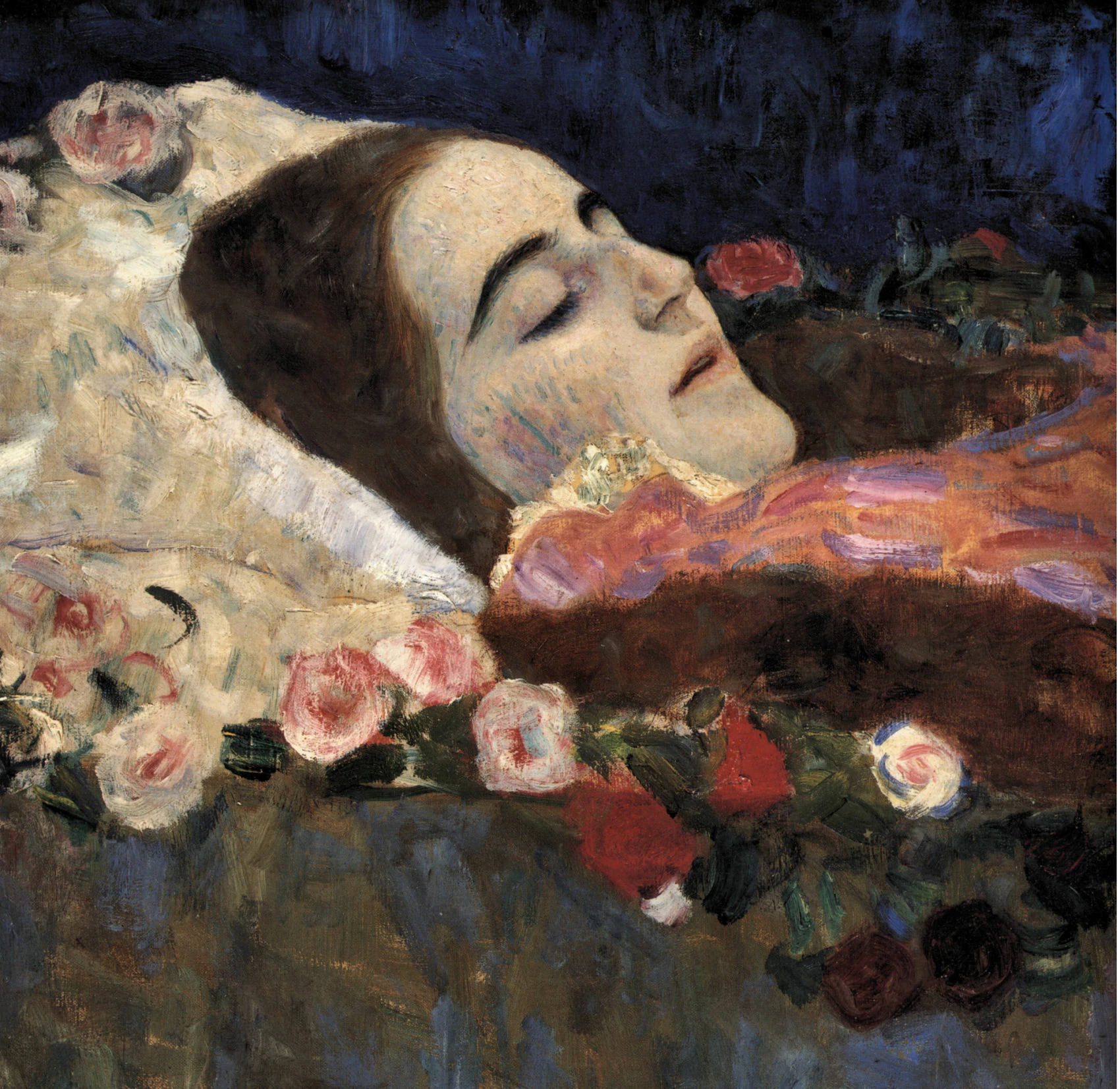

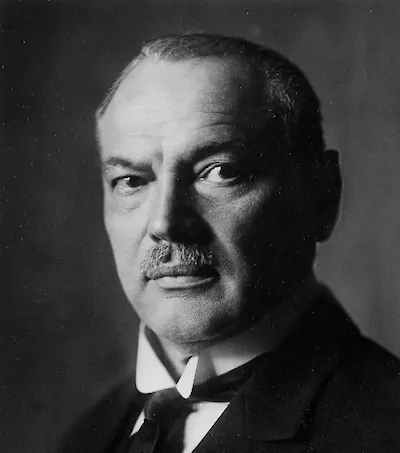

Love of country and love of women

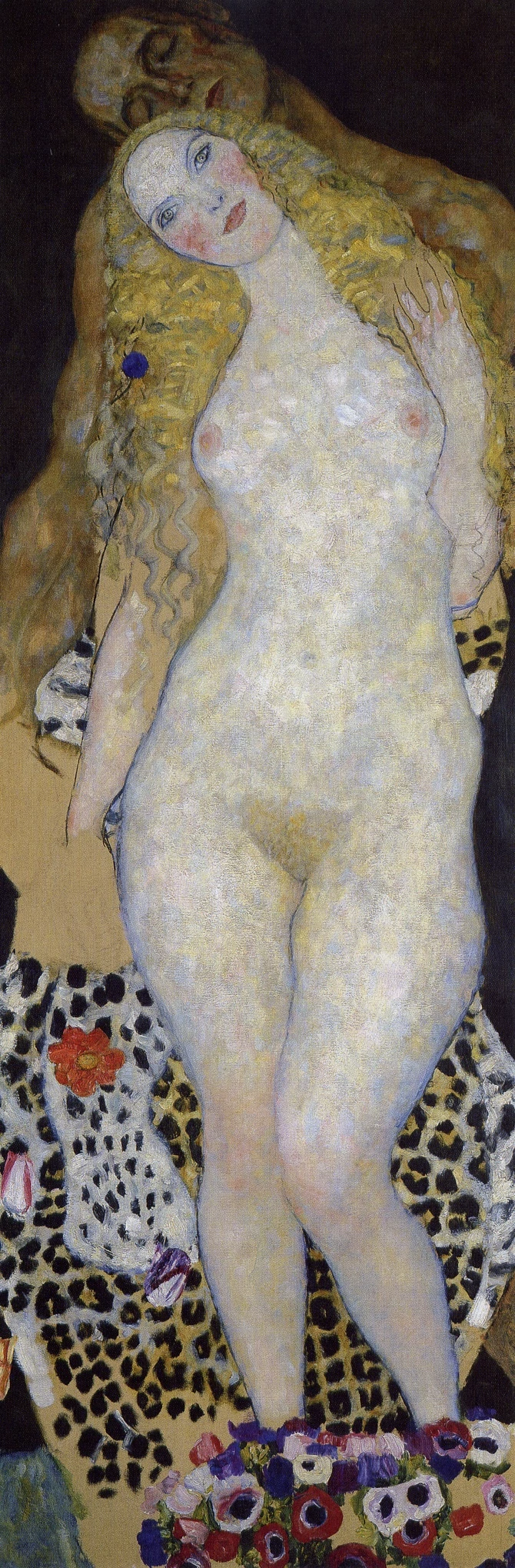

1862 – 1918

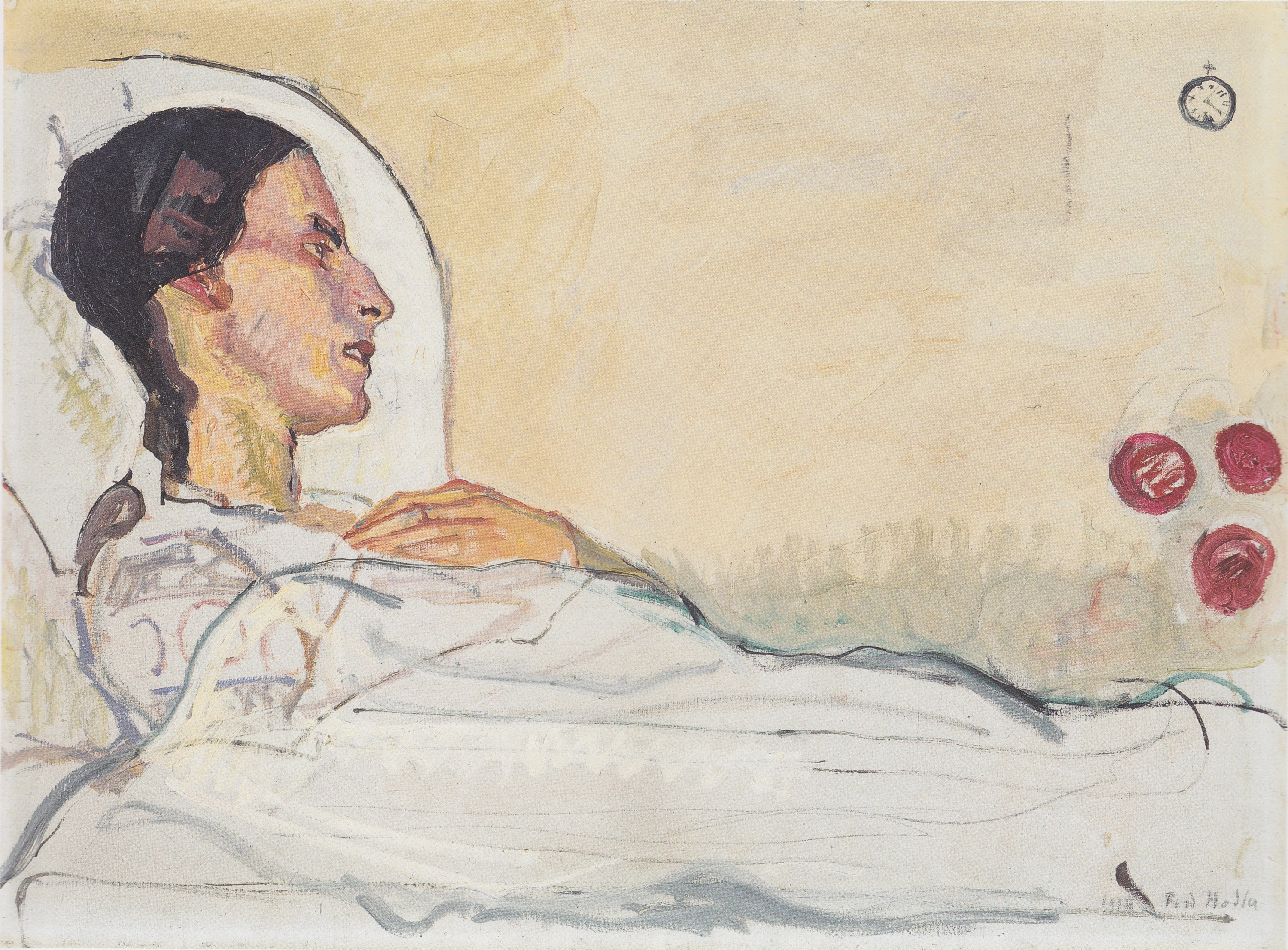

The darkness beckons

1863 – 1928

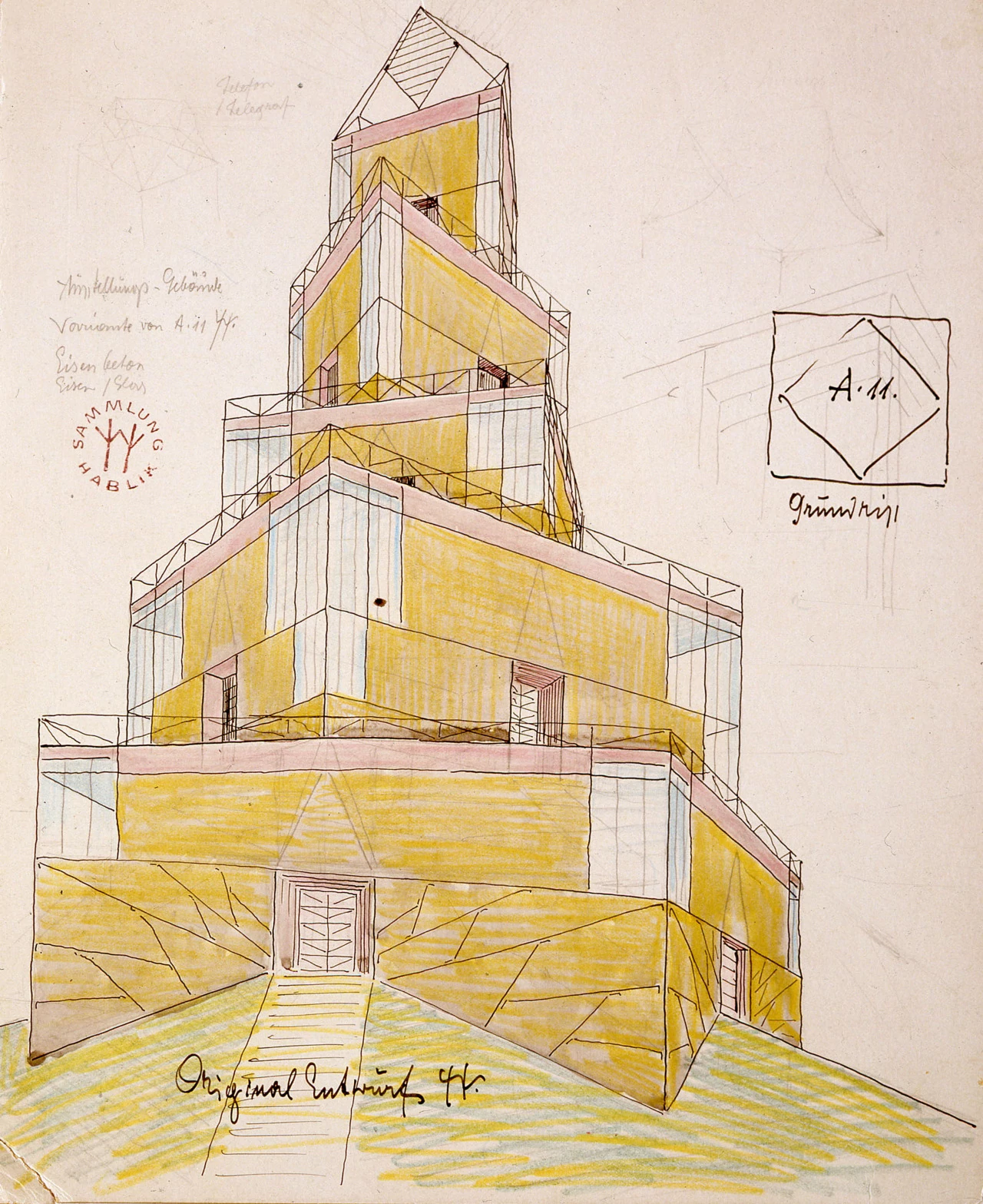

Architect of invisible cities

1881 – 1934

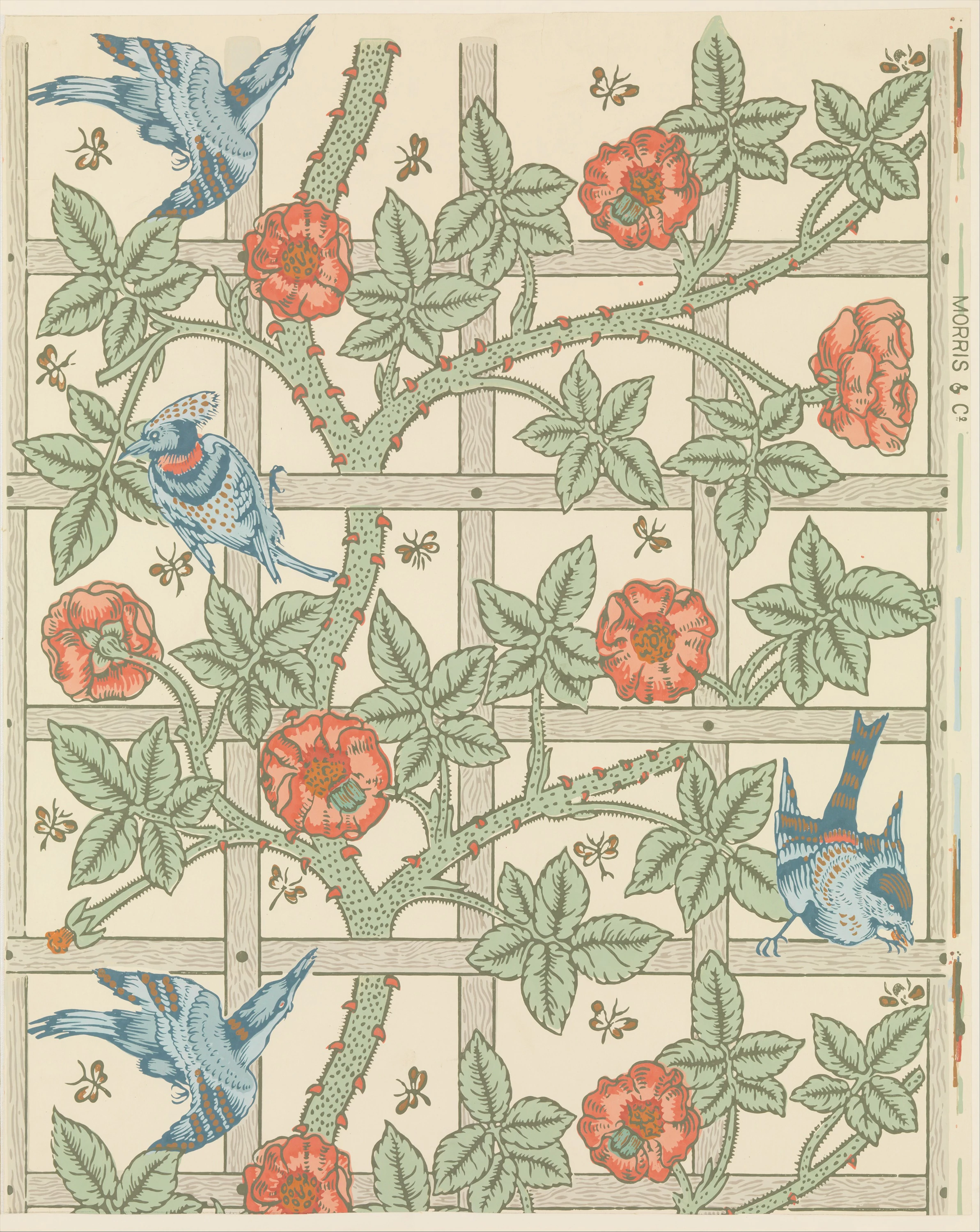

It is right and necessary that all men should have work to do which shall he worth doing

The purpose of applying art: to add beauty to the results of the work of man and to add pleasure to the work itself