From its subject matter and color scheme to the visibility of each brushstroke, Alexandre Cabanel’s artwork was defined by the total authority of the Académie—but even under extreme constraint, creativity finds ways to express itself. In 1795 the state-sponsored French Academies of Music, Architecture, and Painting & Sculpture merged into the Académie des Beaux-Arts, becoming singularly responsible for defining nearly every aspect of French art, and holding final judgment on what was ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art for more than 150 years. An authority this complete is hard to imagine in today’s art world, but the Académie had a monopoly on three critical resources. First, France’s most prestigious art school, the Ecole des Beaux Arts, was run by the Académie, who defined not only its strict curriculum, but the stringent entry requirements that taught young artists to adhere to approved styles before they even began their training. Next, the Académie ran the Paris Salon, the only permitted public art exhibition in France. The exhibition ran only once per year, and entry marked you as a successful artist, leading to sales and commissions from wealthy and powerful patrons—rejection was devastating. Better luck next year. Finally, the Académie put a spotlight on the artist that best exemplified their standards with the Prix de Rome, an annual scholarship that sponsored a trip to Rome for the artist to further refine their technique through study of renaissance art and classical sculpture. Now, back to Cabanel.

Cabanel was the son of a carpenter, born in the fall of 1823 and raised in the small city of Montpellier on the southern coast of France. Precocious and ambitious, he started his artistic training at age ten in the local art school, where he apparently took to drawing so quickly that he was asked to teach classes himself. A few years later in 1839, he won a city-sponsored art competition, and was sent on scholarship to Paris to study in the studio of the influential academic artist Francois-Edouard Picot.

Years before, Picot had won the Prix de Rome scholarship, establishing him as a favorite of the Académie and launching his career. To give his students the best chance at professional success, Picot ran his studio as a training-ground for winning the Prix. Students were systematically taught the figure drawing and compositional techniques required to complete the massive history paintings that the Académie considered to be art’s most important genre, and were pitted against each other in monthly competitions, with winners receiving silver medals. Cabanel thrived in this high-stakes environment, quickly absorbing the themes and styles of academic art. Within a year he was accepted into the Ecole des Beaux Arts, and in 1843 he entered the Prix de Rome competition.

The Prix de Rome would make great reality television. Each year the competition was run slightly differently, but here’s roughly how it worked: Contestants needed to be under 30 years old, have a CV full of awards, and the backing of respected professors of the Académie. These already masterful artists were placed under strict supervision and run through a series of challenges with tight time limits. After each round artists were eliminated until only a handful of top competitors were judged, and the single best artist given the award. In the first challenge, contestants had one day to paint a sketch on a predefined theme. The second challenge was a figure study painted from live models, completed in four, seven-hour sessions. Next, a compositional sketch in oil for a finished work eliminated all but the final contestants. The last challenge was the big one, with each artist sequestered away for seventy-two days to complete a full, large-scale history painting—the pinnacle of academic artistic expression.

All of this may sound like overkill, but the prize was life changing. Five years of artistic training in the Medici palace in Rome with the Academy footing the bill, instant connections with most influential artists and patrons in the world, a near guarantee of a lifetime of financial success, and likely an eventual position on the Academy’s board of artists helping define and enforce artistic expression for the next generation. Yikes. Pressure’s on Cabanel.

...

Cabanel was eliminated in round 2 of his first Prix. The theme was Ulysses Recognized by His Nurse, depicting Homer’s hero returning to his home disguised as a begger after the Trojan war. Six years later Cabanel took another stab at the theme, but Ulysses’ stiff posture and some wonky perspective mark it as still not his best work. 1844. Cabanel entered the Prix again. The scene to depict was of the roman patrician Cincinnatus, humbly plowing his fields when summoned by the roman senate to lead the republic through a time of crisis. Good material, and this time Cabanel made it to the final round, though he placed sixth among the finalists, and Félix-Joseph Barrias took the prix (Barrias later tutored the man many credit with the end of Academic art: Edgar Degas, small world).

1855. Third time’s the charm right? But that year the judges were vicious. One hundred sixteen artists entered, just over twenty made it through the first round. Cabanel passed. Second round only ten artists made it though. Cabanel passed. The theme for the final history painting was Jesus’s trial before Pontius Pilate in the Roman praetorium. Cabanel’s 12 hour sketch landed him in the final challenge, and he entered seclusion to complete a final work, emerging 72 days later in September, just two days before his 22nd birthday.

Second place. Though his previous attempts had taught Cabanel how to play to the tastes of the Académie—earth tone palette with pop of red, immaculate flesh tones, hints of oversized architecture—his characters were too vigorous, too expressive. His fellow student under Picot, Leon Benouville, took first place with his more symmetrical, almost byzantine Christ and classical triangular composition. But the judges were nearly split, and when no Prix was awarded in the musical category, a new award was invented for Cabanel: “Second First Grand Prize.” Alexandre was going to Rome.

The pressures of the Académie continued once the Prix winners got to Rome. At specific dates during their stay, they were required to send artwork back to Paris for judgment. Cabanel’s first artwork was Orestes, submitted for review in 1846 and featuring the matricidal Greek in the nude and accosted from the shadows by the three furies. It’s a dark, brooding work, its titular subject facing away from the viewer but reaching out to them in fear or supplication. The Academy was not into it, too expressive. The following year Cabanel took an almost defiant stand with his envoy—submitting the fiercely dramatic, L’Ange Dechu, the Fallen Angel.

I'm giving a whole section to this bad boy because it’s one of my favorite artworks, and because Tiktok has embraced this recumbent angel and brought me tons of traffic. Cabanel lived and worked in the midst of a cultural shift we now call The Enlightenment, a movement towards reason, knowledge, humanism and science. Religious themes were still popular in art during this time, but the flavor changed, and Cabanel’s furious angel is a perfect example. First, this image isn't from a bible story, but depicts Beelzebub, better known as Lucifer, as he is captured in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Lucifer was an Enlightenment hero—the original iconoclastic free-thinker, and Cabanel poured every ounce of his training and skill into flashing a dozen expressions across the angel’s beautiful face. It was a shock to the salon. No other student has submitted a, uh, satan? Too expressive, too romantic, just too much. “…That’s my reward for all the trouble I gave myself not to submit an average piece of work…” wrote Cabanel in a letter to his friend and patron Alfred Bruyas.

...

Cabanel’s last submission from Rome was easily his most ambitious. Inspired by a visit to the Pitti Palace in Naples, where he saw Raphael’s The Vision of Ezekiel, Cabanel sketched a dying Moses, arms outstretched as he is welcome into the arts of angels and a bare chested, backlit Elohim. In a letter to his brother, Cabanel wrote “I have imposed myself a large, very difficult, formidable task, since I seek to represent the image of the Eternal Master of the sky and the earth—to represent God—and next to Him, one of His most sublime creatures, deified in some way by His contact.” Cabanel pulled out all the stops. Jewel-tone textiles, butterfly-winged angels, a sunset’s dramatic light, even Moses has rays of light shooting out of head, all in a dramatic composition that diagonally bisects the monumental six by nine foot canvas.

The project so preoccupied Cabanel that he painted the image twice, the original, and a half-size reduction that added more room around the central figures. A perfectionist compulsion that makes the still-young artist all the more relatable. Despite his perseverating, back in France the Death of Moses (the big one) won second place in the 1852 Salon, and finally the tide of public opinion began to turn in Cabanel’s favor. His wealthy young friend Alfred Bruyas stepped up his patronage, he was commissioned to create illustrations for the complex geometries of the pendentives (shapes connecting a circular dome to a square room) of the Hotel de Ville, and eventually became a go-to resource for Napoleon III’s Director of Fine Arts Marquis Philippe de Chennevieres, who commissioned many grand works on behalf of France’s second empire.

Though Cabanel’s place at the academic table was hard won, his trajectory to success started young, and he became one of the rare artists whose career was long, influential, and very lucrative. By age 40 Cabanel was an institution. A confident, respected, and prolific artist, who, despite a youth spent straining against the nuance of Academic doctrine, had finally earned acceptance and influence.

This mature Cabanel painted the artwork we know him best for: The Birth of Venus. It’s a classical theme that has been re-envisioned again and again, but I think Cabanel’s goddess is the most refined version ever created. No clam shell, no contrapposto. Just ivory skin on a graceful body, rendered with a naturalism that belies the subject’s divine origin. It’s perfect, and everyone knew it. Including Napoleon III, who saw it in the 1863 Salon, and immediately purchased it.

While Cabanel reigned supreme as one of the most respected and powerful artists of his day, a revolution was building that soon overshadowed the entire establishment he’s worked so hard to earn a place within. The same year as his Birth of Venus was exhibited in the Salon, another artist’s work was rejected: Edouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, a stark and unromantic image that many cite as the beginning of the more jaded, honest, populist art that became modernism. But this revolution was probably just a passing curiosity for Cabanel, whose studio was booked solid with portrait commissions for the rich, famous, and politically influential, and grand decorative set pieces to adorn the new wealth of the late 19th century.

Cabanel’s greatest influence was in his role as a teacher. Like his own teacher Picot, Cabanel was appointed a professor at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, served on seventeen juries for the Salon, and taught dozens if not hundreds of students, many of whom won the Prix de Rome themselves. Cabanel was known to embrace the temperaments of his students, encouraging even “the most dissimilar of minds” to excel even in styles that were different than his own.

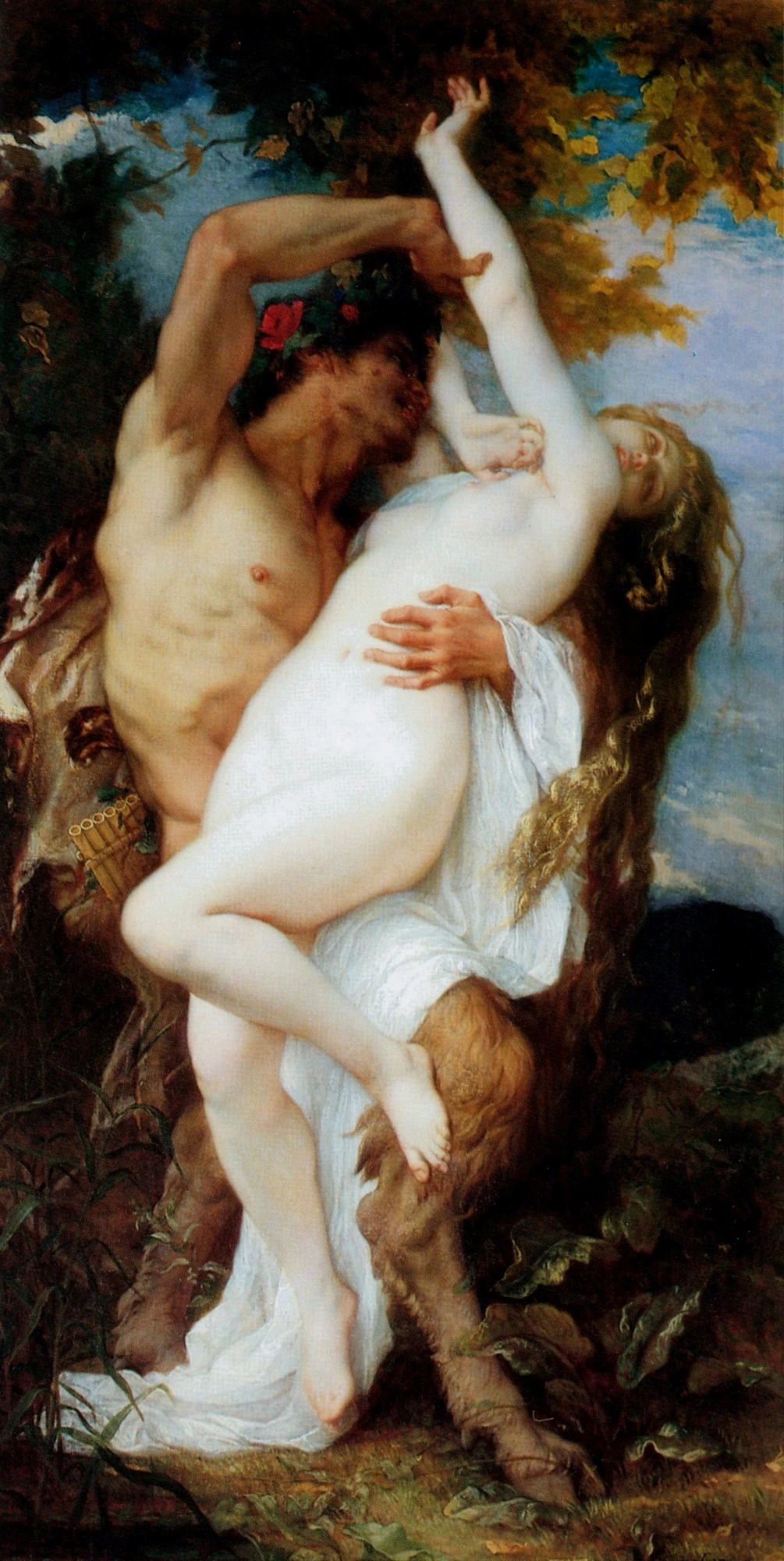

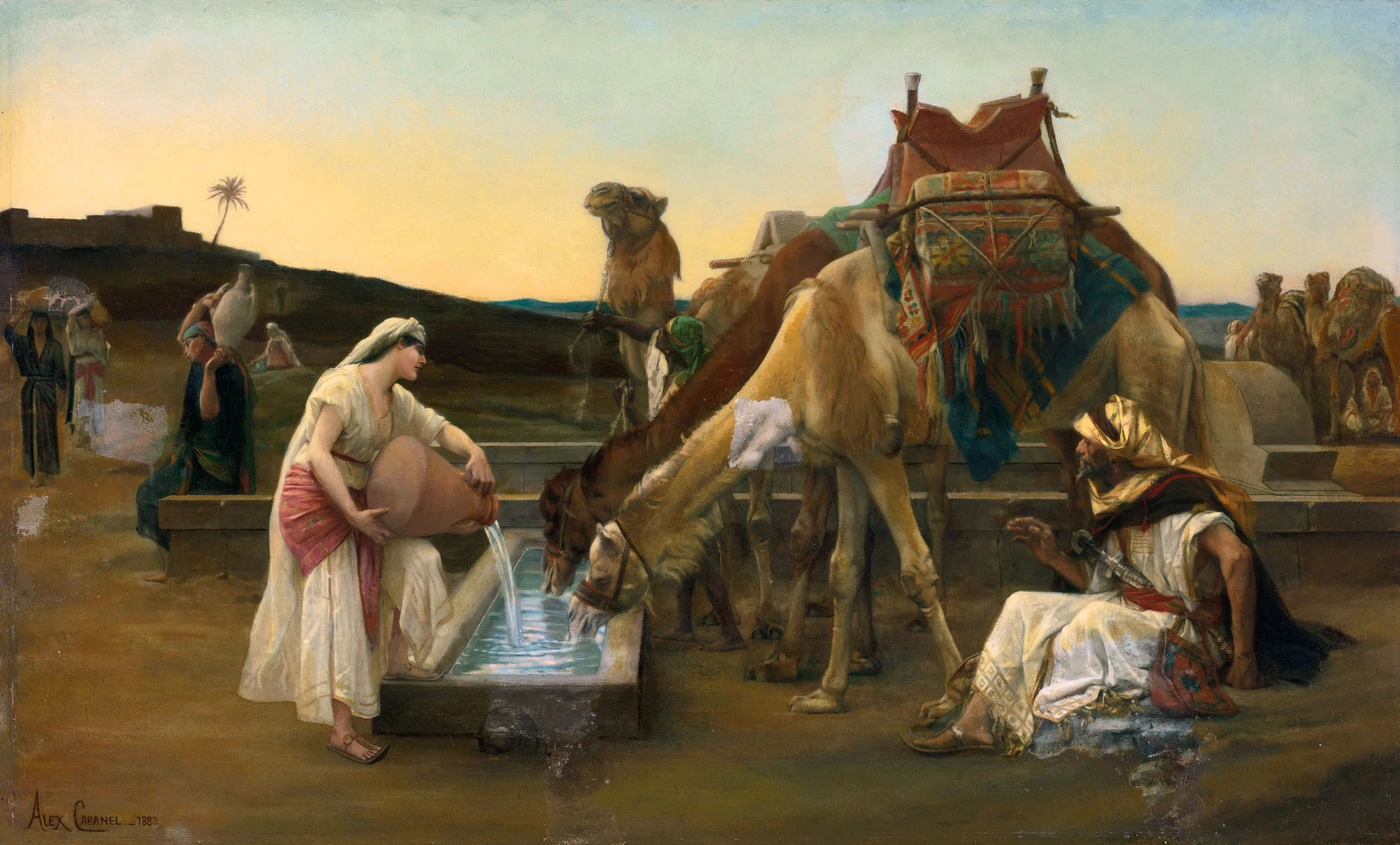

In some ways it’s easy to dismiss the work of the Academic artists—it was dogmatic, formal, prescriptive, and tailored to an isolated aristocracy. But you've got to hand it to Cabanel, even in the last decade of his life he explored new styles and pushed his skill to new heights, delving into obscure historical scenarios through the newly popular lens of Orientalism, exploring the apocryphal story of Sarah and Tobit in Prayer, the roman historian Livy’s account of Lucretia and Sextus Tarquin, the brutal and confusing tragedy of Phaedra haunted by the memory of the stepson she conspired to murder, and the spectacular and grim Cleopatra testing poisons on Condemned Prisoners, where the suicidal queen stoically measures which poisons kill most painlessly.

Cabanel’s own life ended relatively young, when he succumbed to a long running asthma attack at age 65. The dawn of the 20th century saw the overthrow of the Academy, as avant garde movements erased the long-held neoclassicism of the French schools in favor of a plethora of new movements—impressionism, Fauvism and the fractured artistic landscape of the First World War. But while the end of Academicism’s dominance was overdue, there is much to learn from the dedication and struggle of a young artist to succeed within the constraints of his time, and once successful, to foster the skills and perspectives of those who sought to learn how to create great art.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Alexandre Cabanel? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.