Vienna Secession

"To every age its art. To art its freedom."

It was 1897, and art in Vienna was stuffy. The Association of Austrian Artists, the dominant body of Viennese artists and gallerists, held court from the Künstlerhaus, a doudy, renaissance-style manor on the Ringstraße. The AAA were notoriously classical in their tastes and commercial in motivation, and they all but held the keys to financing and Vienna’s few gallery spaces. While the rest of the world was exploring the exciting and provocative styles of Modernism, Vienna had stalled out.

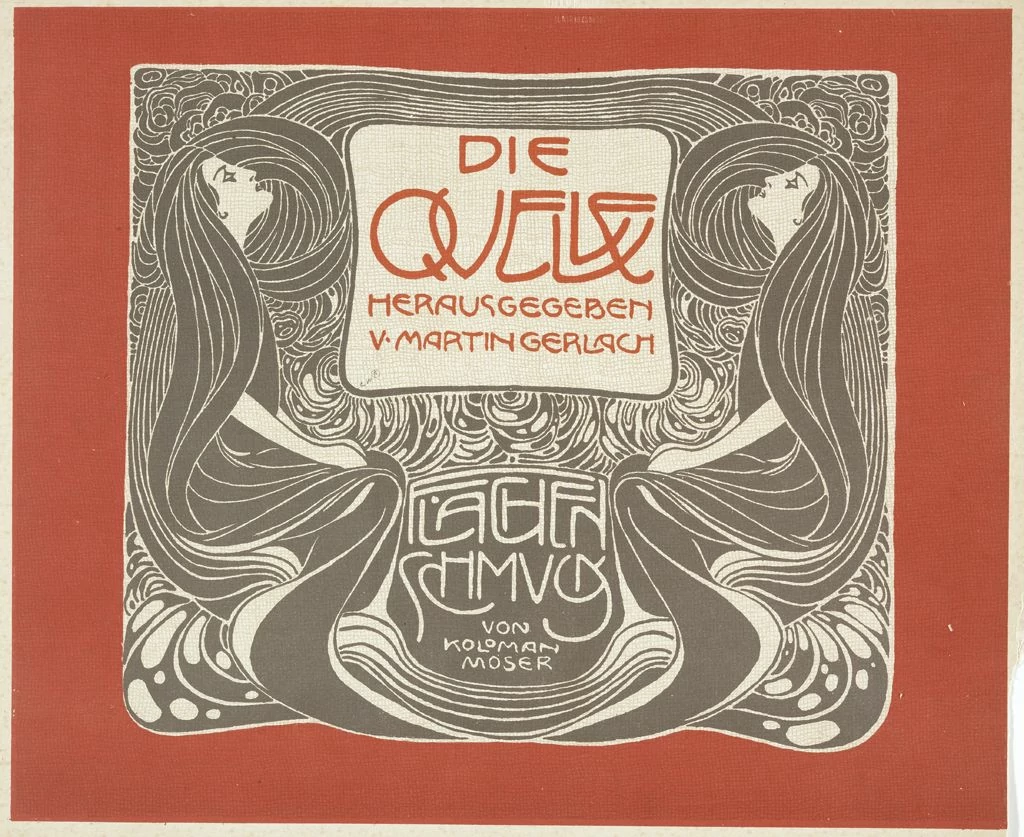

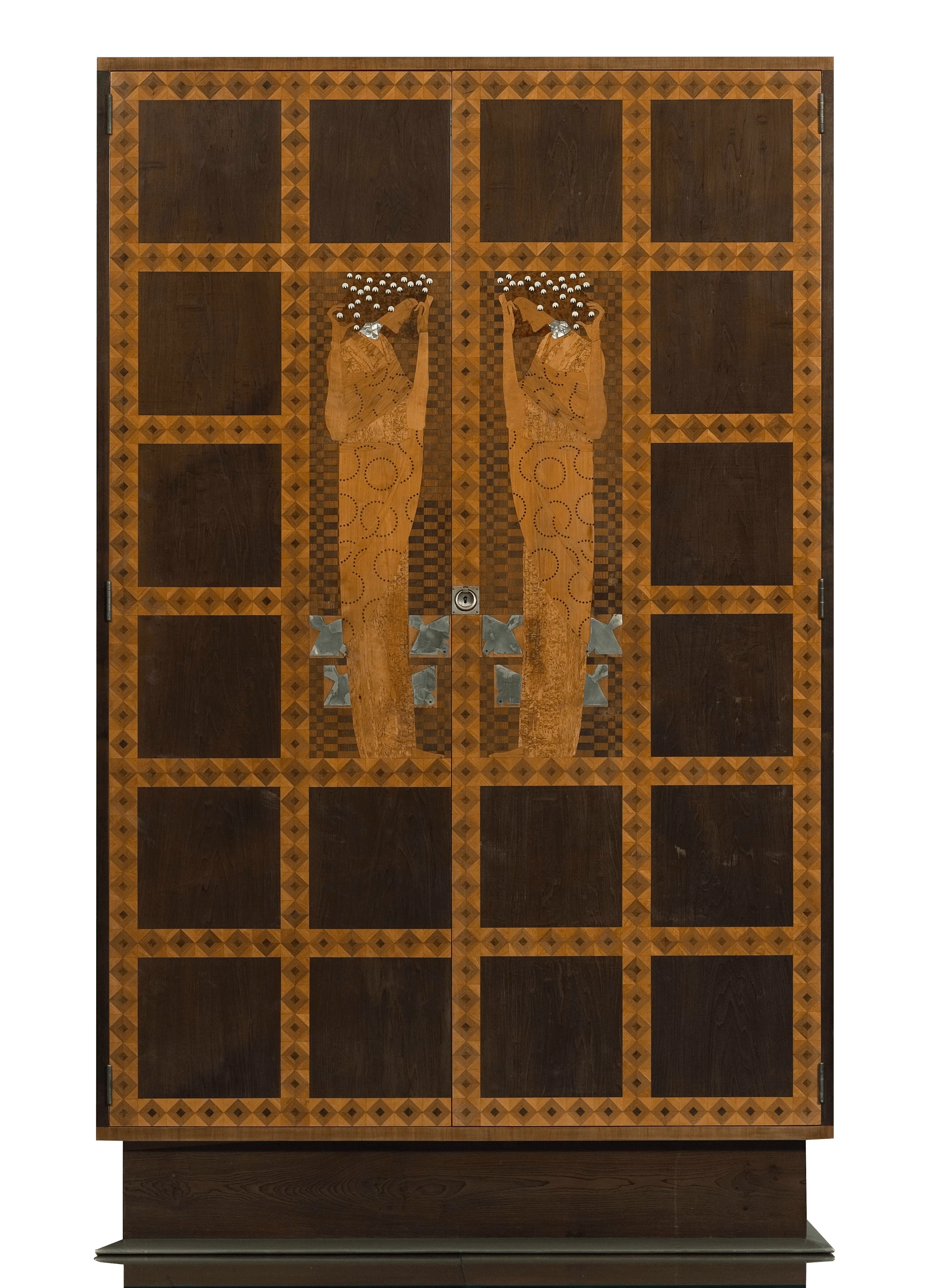

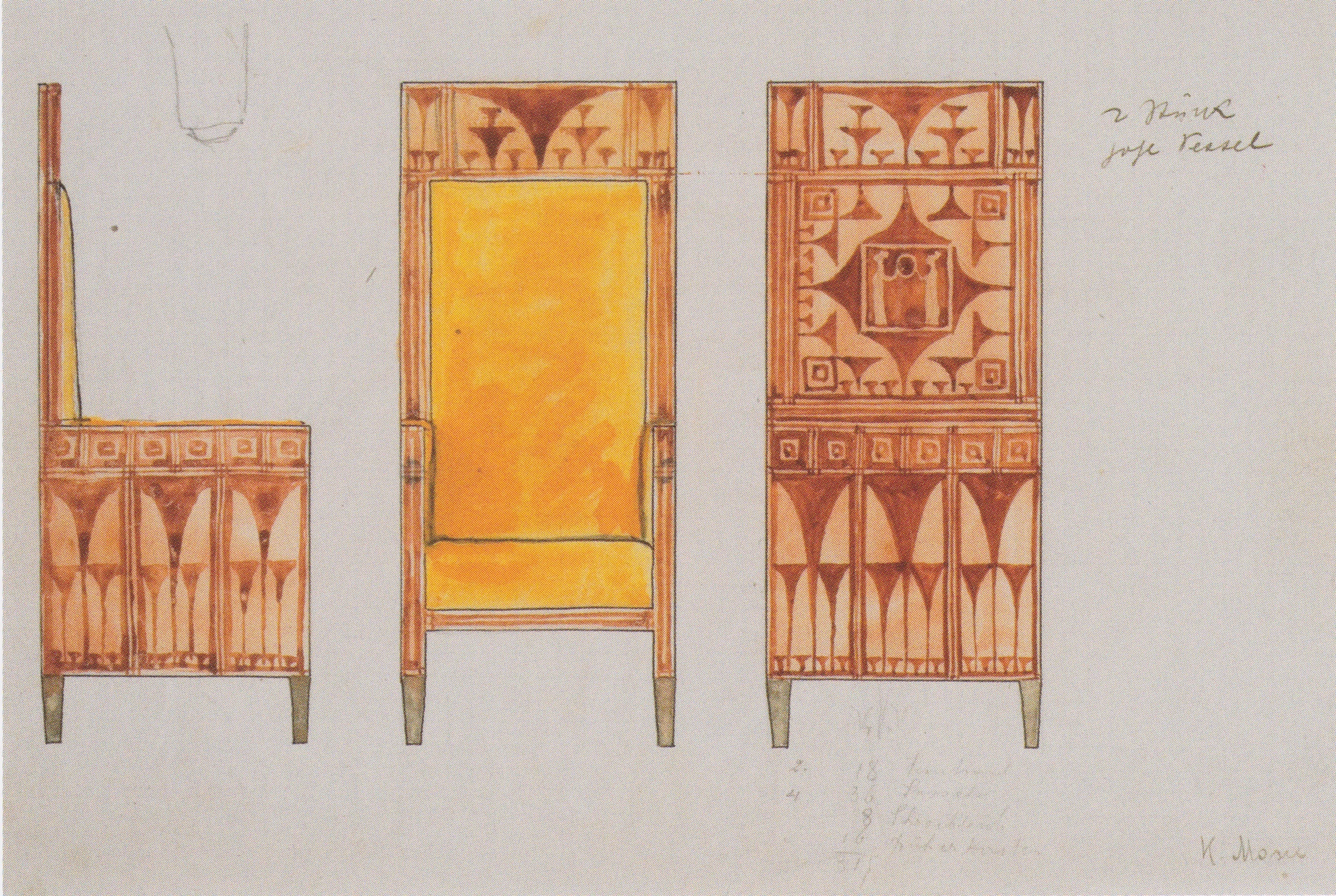

The claustrophobic system needed subversion, and a few young members of the AAA began meeting in coffee shops to plan a reformation. It was a diverse group of disaffecteds, including the industrial designer Koloman Moser, art nouveau painter Carl Moll, and the architect Josef Hoffmann, but they shared a common desire to broaden the artistic practice to include product and interior design, decorative arts, typography, architecture, textiles and more, and in each discipline to connect with craftsman and production houses to bring their new style to the masses.

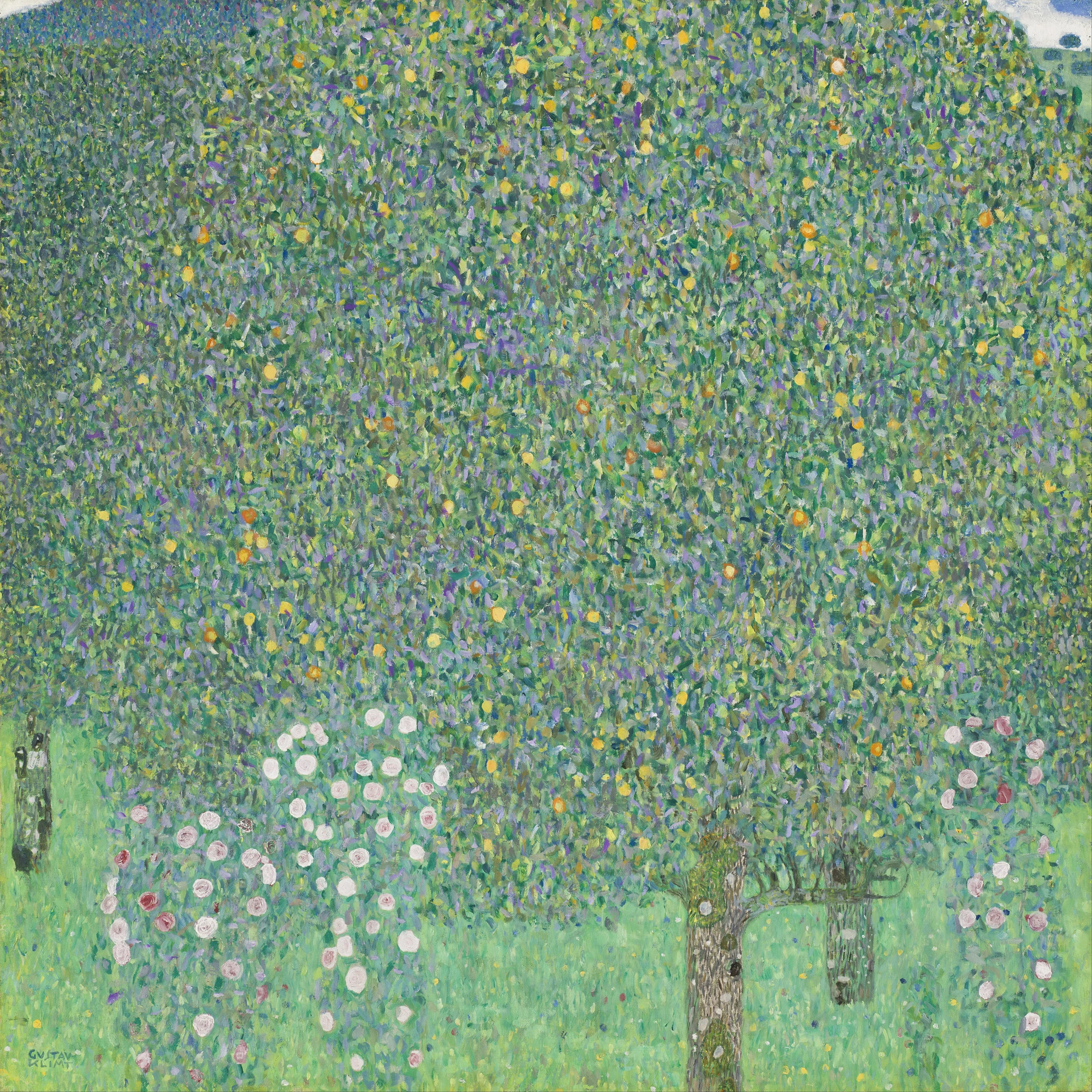

On April 3rd, 1897, our young modernists asked Gustav Klimt, already a respected and successful artist, to lead them in the Vienna Secession. A letter, read aloud by Klimt in the Künstlerhaus, declared the formation of a new group, the Union of Austrian Artists, and was signed by 40 members, including many members of the AAA. Unsurprisingly, they were asked to leave the building, and two days later, forced to resign from the AAA. Like it or not, Klimt and Moll and Moser and their chaotic posse of artists and designers were on their own.

Which brings us to the reason why it’s difficult to talk about the Vienna Secession as a movement. While its members were aligned in their ideals, and contributed to Ver Sacrum, the secession’s magazine, and hung out in architect Joseph Maria Olbrich’s Secession Building, their shiny new gallery space funded by a local steel tycoon, the Secession wasn’t a style. Visually, Secession art and design often feels similar to Jugendstil, or Germany’s flavor of Art Nouveau, both influenced by globalization, exposure to Japanese woodblock prints, Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, and Aubrey Beardsley’s Salome. The Arts and Crafts movement was another major influence, with its focus on geometry, symmetry, and aestheticising of everyday objects.

Secession art feels decidedly ‘of its time’ but it was the shift in power that it represented that’s important. From a single-voiced academic mono-culture, to diverse, individual expression. From locked-down art venues to communal space, and from painting and sculpture to a broad array of manufactured goods, products, and spaces. Many modern movements attacked the old definitions of art—the Secession tore down the system that supported it.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Vienna Secession? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.