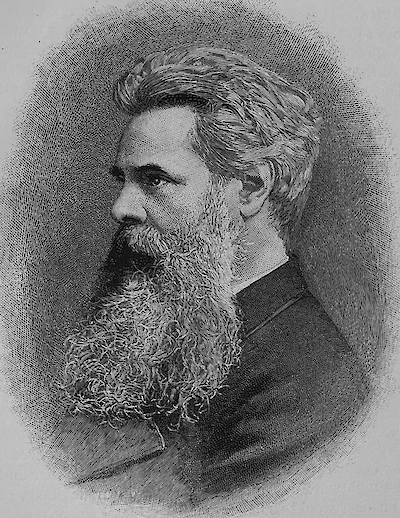

Thomas Woolner

Sculptor turned poet, Pre-Raphaelite turned Neoclassicist

1825 – 1892All seems a painted show. I look

Up thro’ the bloom that’s shed

By leaves above my head,

And feel the earnest life forsook

All being, when she died:—

My heart halts, hot and dried

As the parched course where once a brook

Thro’ fresh growth used to flow,—

Because her past is now

No more than stories in a printed book.

The grass has grown above that breast,

Now cold and sadly still,

My happy face felt thrill:—

Her mouth’s mere tones so much expressed!

Those lips are now close set,—

Lips which my own have met;

Her eyelids by the earth are pressed;

Damp earth weighs on her eyes;

Damp earth shuts out the skies.

My lady rests her heavy, heavy rest.

To see her slim perfection sweep,

Trembling impatiently,

With eager gaze at me!

Her feet spared little things that creep:—

“We've no more right,” she'd say,

“In this the earth than they.”

Some remember it but to weep.

Her hand’s slight weight was such,

Care lightened with its touch;

My lady sleeps her heavy, heavy sleep.

My day-dreams hovered round her brow;

Now o'er its perfect forms

Go softly real worms.

Stern death, it was a cruel blow,

To cut that sweet girl’s life

Sharply, as with a knife.

Cursed life that lets me live and grow,

Just as a poisonous root,

From which rank blossoms shoot;

My lady’s laid so very, very low.

Dread power, grief cries aloud, “unjust,”—

To let her young life play

Its easy, natural way;

Then, with an unexpected thrust,

Strike out the life you lent,

Just when her feelings blent

With those around whom she saw trust

Her willing power to bless,

For their whole happiness;

My lady moulders into common dust.

Small birds twitter and peck the weeds

That wave above her head,

Shading her lowly bed:

Their brisk wings burst light globes of seeds,

Scattering the downy pride

Of dandelions, wide:

Speargrass stoops with watery beads:

The weight from its fine tips

Occasionally drips:

The bee drops in the mallow-bloom, and feeds.

About her window, at the dawn,

From the vine’s crooked boughs

Birds chirupped an arouse:

Flies, buzzing, strengthened with the morn;—

She’ll not hear them again

At random strike the pane:

No more upon the close-cut lawn,

Her garment’s sun-white hem

Bend the prim daisy’s stem,

In walking forth to view what flowers are born.

No more she’ll watch the dark-green rings

Stained quaintly on the lea,

To image fairy glee;

While thro’ dry grass a faint breeze sings,

And swarms of insects revel

Along the sultry level:—

No more will watch their brilliant wings,

Now lightly dip, now soar,

Then sink, and rise once more.

My lady’s death makes dear these trivial things.

Within a huge tree’s steady shade,

When resting from our walk,

How pleasant was her talk!

Elegant deer leaped o'er the glade,

Or stood with wide bright eyes,

Staring a short surprise:

Outside the shadow cows were laid,

Chewing with drowsy eye

Their cuds complacently:

Dim for sunshine drew near a milking-maid.

Rooks cawed and labored thro’ the heat;

Each wing-flap seemed to make

Their weary bodies ache:

The swallows, tho’ so very fleet,

Made breathless pauses there

At something in the air:—

All disappeared: our pulses beat

Distincter throbs: then each

Turned and kissed, without speech,—

She trembling, from her mouth down to her feet.

My head sank on her bosom’s heave,

So close to the soft skin

I heard the life within.

My forehead felt her coolly breathe,

As with her breath it rose:

To perfect my repose

Her two arms clasped my neck. The eve

Spread silently around,

A hush along the ground,

And all sound with the sunlight seemed to leave.

By my still gaze she must have known

The mighty bliss that filled

My whole soul, for she thrilled,

Drooping her face, flushed, on my own;

I felt that it was such

By its light warmth of touch.

My lady was with me alone:

That vague sensation brought

More real joy than thought.

I am without her now, truly alone.

We had no heed of time: the cause

Was that our minds were quite

Absorbed in our delight,

Silently blessed. Such stillness awes,

And stops with doubt, the breath,

Like the mute doom of death.

I felt Time’s instantaneous pause;

An instant, on my eye

Flashed all Eternity:—

I started, as if clutched by wild beasts’ claws,

Awakened from some dizzy swoon:

I felt strange vacant fears,

With singings in my ears,

And wondered that the pallid moon

Swung round the dome of night

With such tremendous might.

A sweetness, like the air of June,

Next paled me with suspense,

A weight of clinging sense—

Some hidden evil would burst on me soon.

My lady’s love has passed away,

To know that it is so

To me is living woe.

That body lies in cold decay,

Which held the vital soul

When she was my life’s soul.

Bitter mockery it was to say—

“Our souls are as the same:”

My words now sting like shame;

Her spirit went, and mine did not obey.

It was as if a fiery dart

Passed seething thro’ my brain

When I beheld her lain

There whence in life she did not part.

Her beauty by degrees,

Sank, sharpened with disease:

The heavy sinking at her heart

Sucked hollows in her cheek,

And made her eyelids weak,

Tho’ oft they'd open wide with sudden start.

The deathly power in silence drew

My lady’s life away.

I watched, dumb with dismay,

The shock of thrills that quivered thro'

And tightened every limb:

For grief my eyes grew dim;

More near, more near, the moment grew.

O horrible suspense!

O giddy impotence!

I saw her fingers lax, and change their hue.

Her gaze, grown large with fate, was cast

Where my mute agonies

Made more sad her sad eyes:

Her breath caught with short plucks and fast:—

Then one hot choking strain.

She never breathed again:

I had the look which was her last:

Even after breath was gone,

Her love one moment shone,—

Then slowly closed, and hope for ever passed.

Silence seemed to start in space

When first the bell’s harsh toll

Rang for my lady’s soul.

Vitality was hell; her grace

The shadow of a dream:

Things then did scarcely seem:

Oblivion’s stroke fell like a mace:

As a tree that’s just hewn

I dropped, in a dead swoon,

And lay a long time cold upon my face.

Earth had one quarter turned before

My miserable fate

Pressed on with its whole weight.

My sense came back; and, shivering o'er,

I felt a pain to bear

The sun’s keen cruel glare;

It seemed not warm as heretofore.

Oh, never more its rays

Will satisfy my gaze.

No more; no more; oh, never any more.