Orientalism

The western fantasy

During the early 1800s the world was getting smaller. The recently invented steam ship made intercontinental travel more predictable, and colonial expansion by Europe’s imperial powers was in full swing. Napoleon botched an invasion of Egypt and Syria, France invaded Algeria, and the crumbling Ottoman Empire left much of the Middle East and Northern Africa vulnerable to Europe’s expanding colonization. In this dawn of globalization an art movement emerged mirroring the political interest in these ‘exotic’ locations, and the visual vocabulary of Islamic architecture, textiles and culture became a fixation for an entire generation of academic artists.

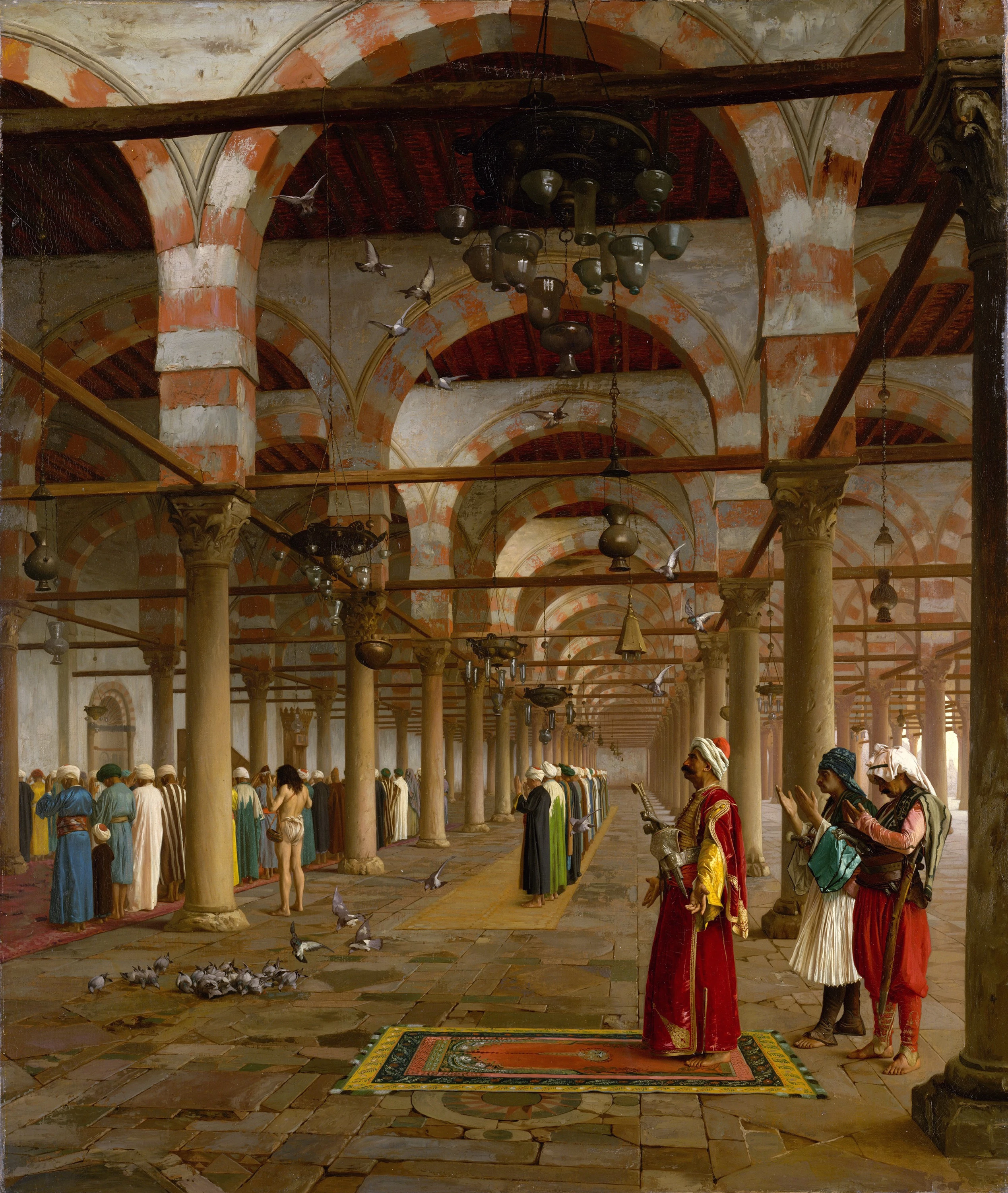

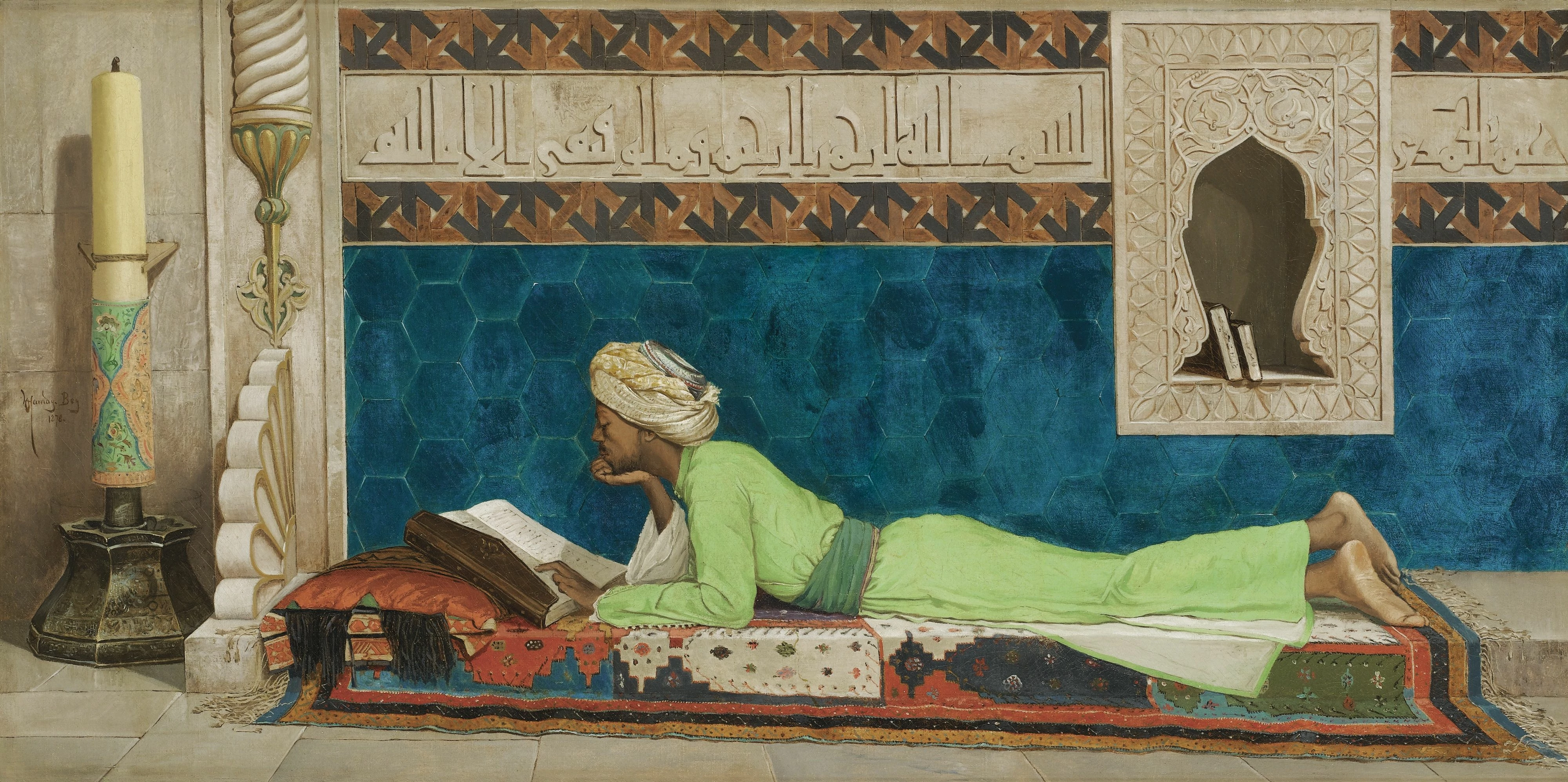

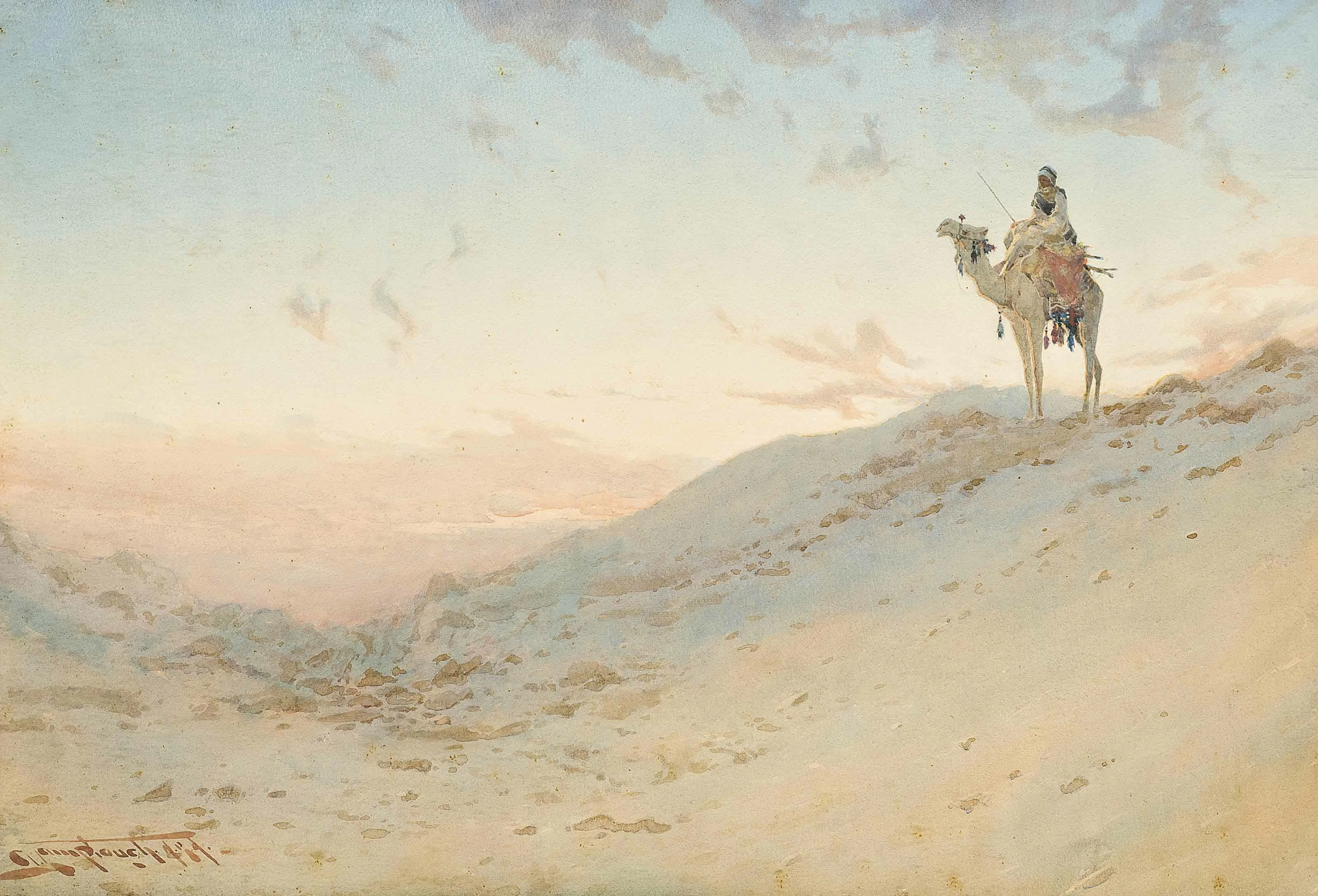

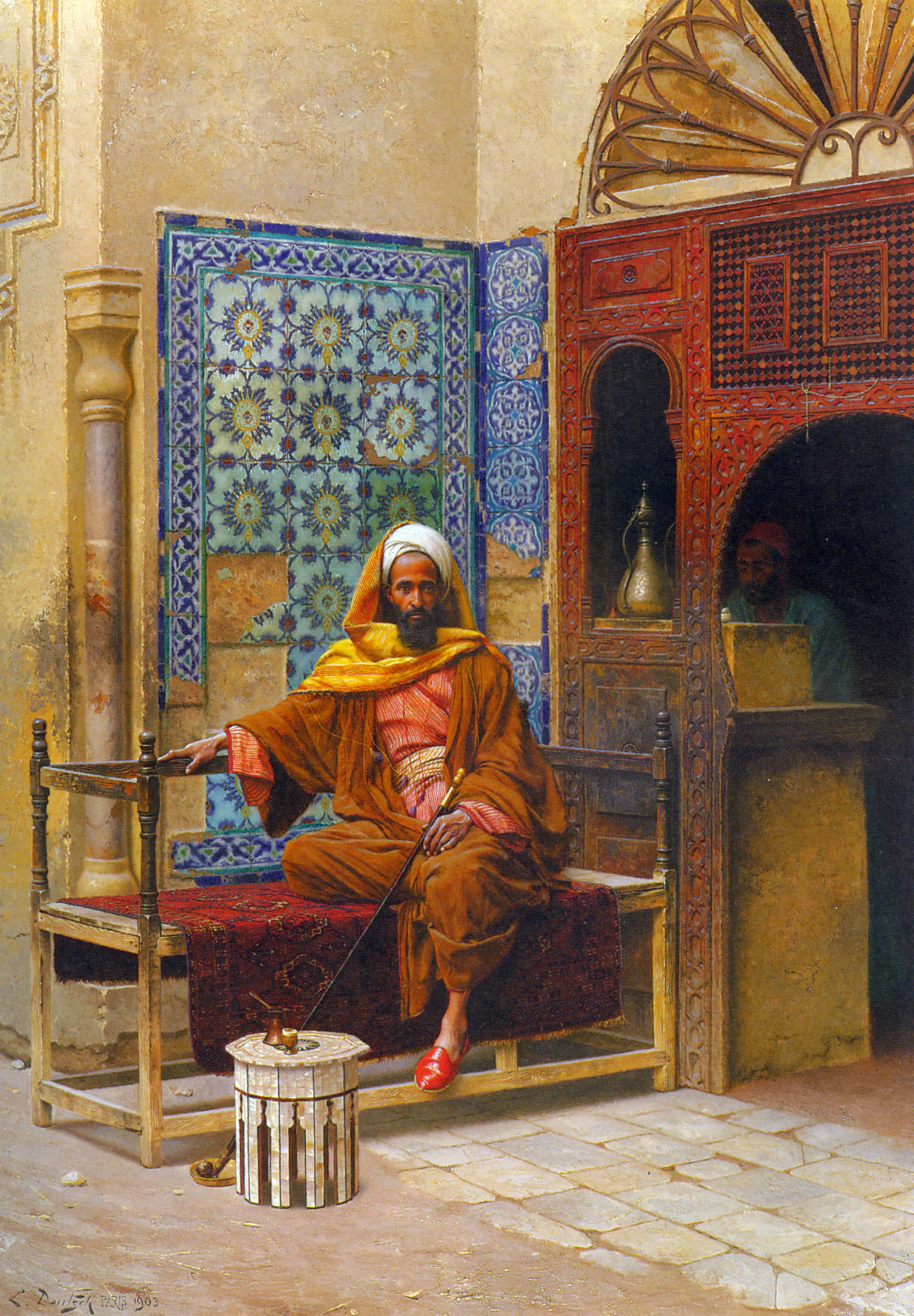

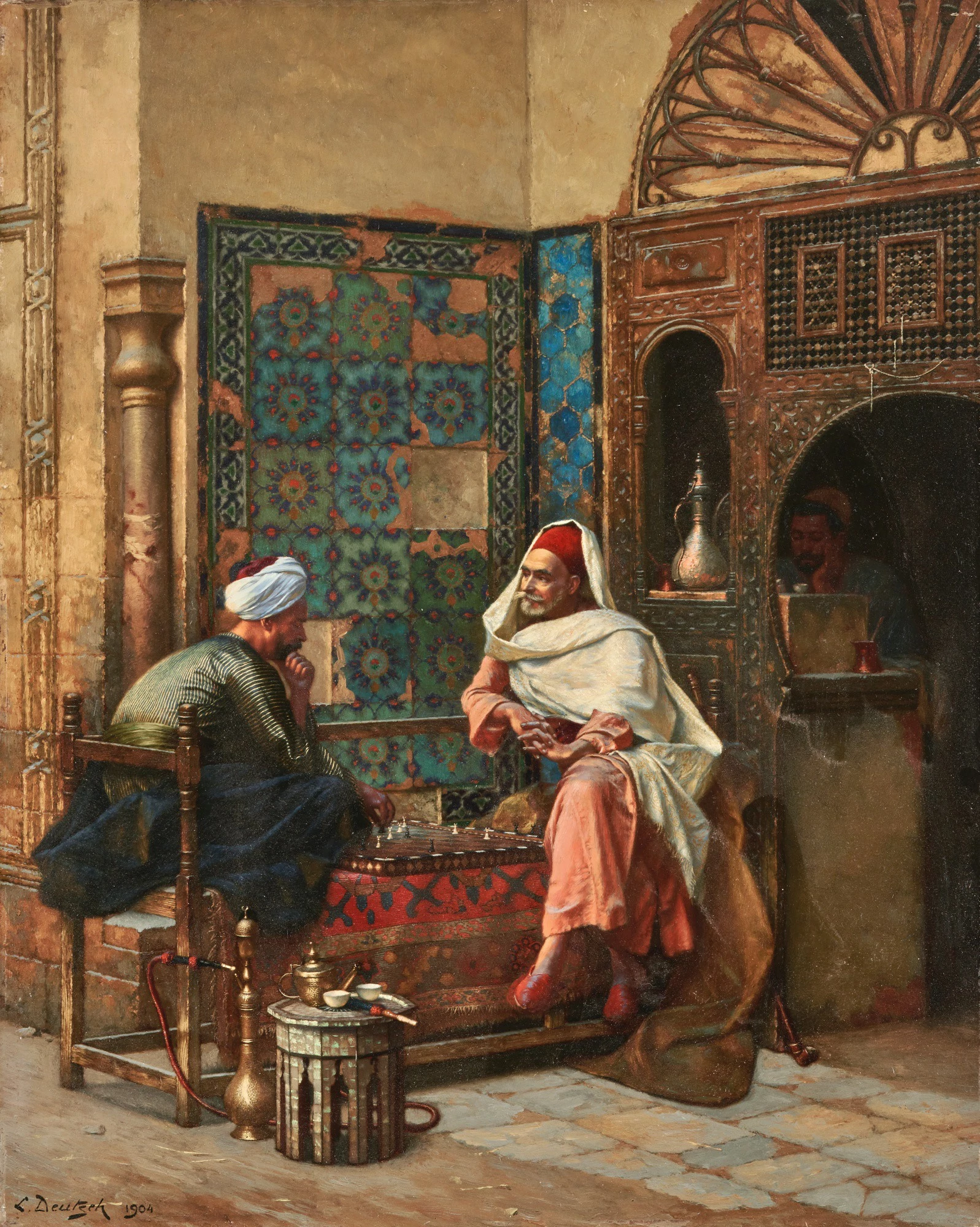

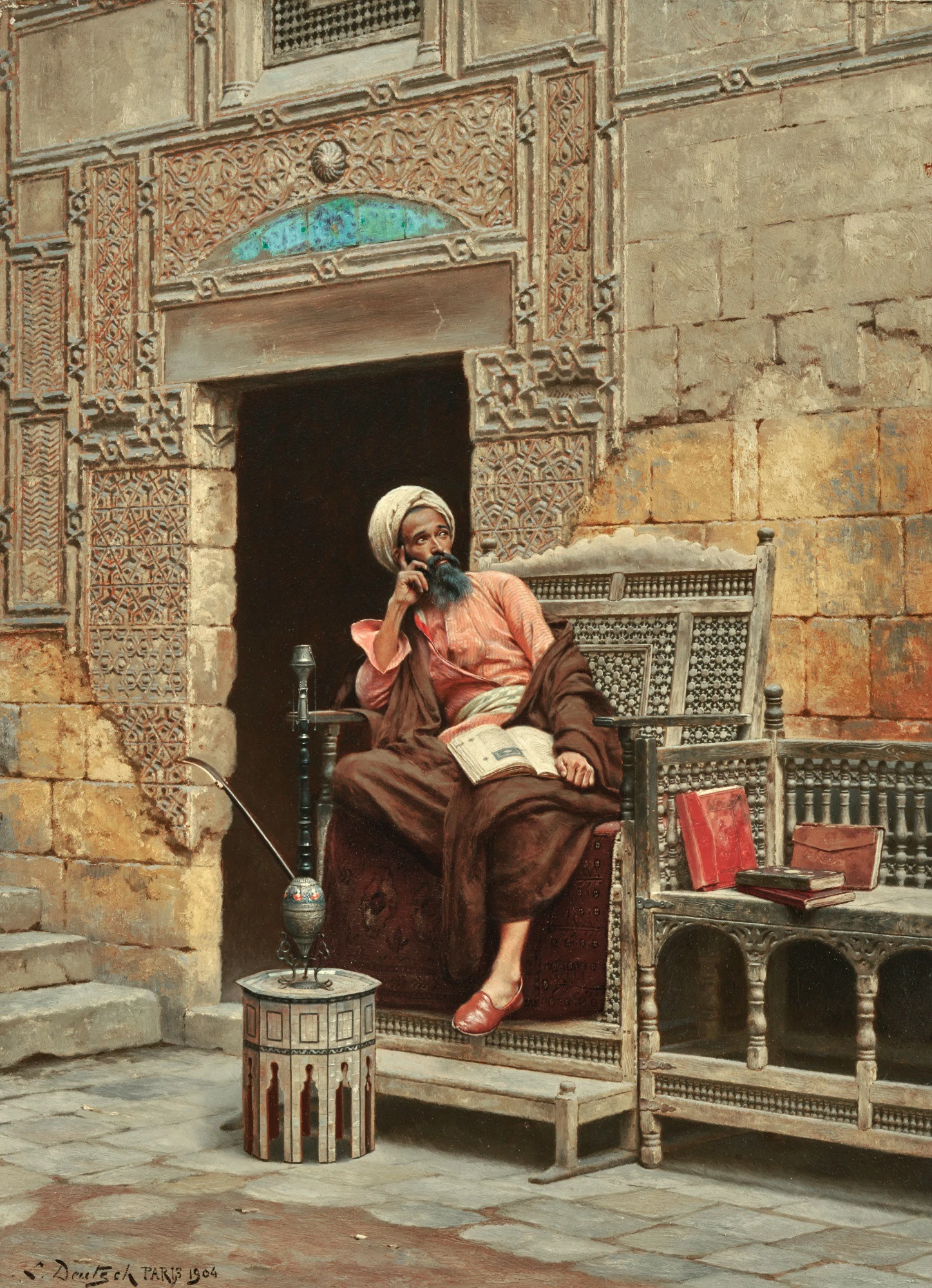

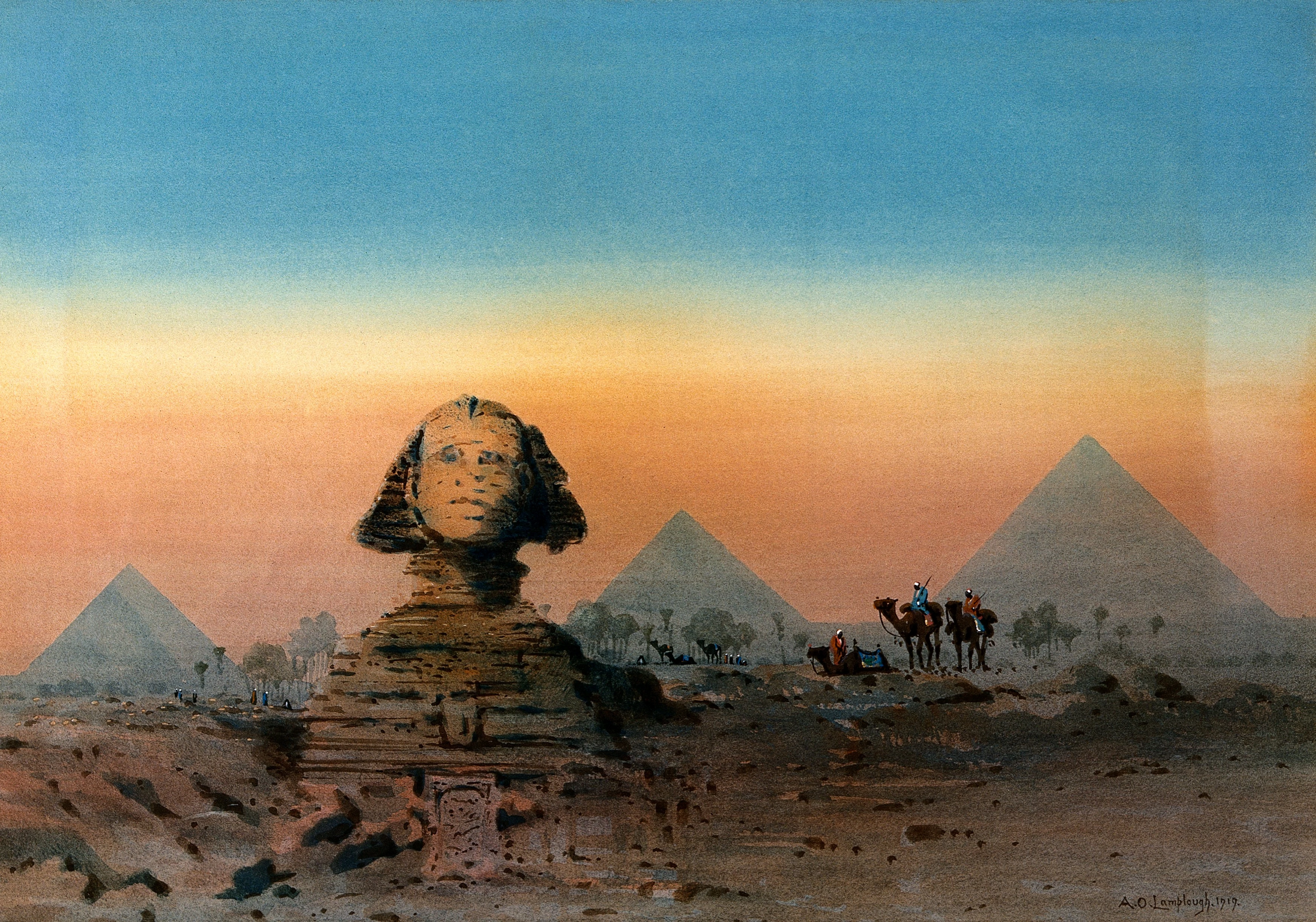

In a strictly formal sense, orientalist art is a fascinating juxtaposition. Emerging at the height of the French and English academic art world, most orientalist artists were rigorously trained, applying a renaissance-worth of rendering technique and tradition to create startlingly life-like paintings. And after centuries of classical history painting, Christian religious art and portraits of the European elite, the ornamental architecture, patterned textiles and rich environments of the orient were a novel change. At its best, orientalist art feels like a fusion of European technique and Arab-Islamic subjects.

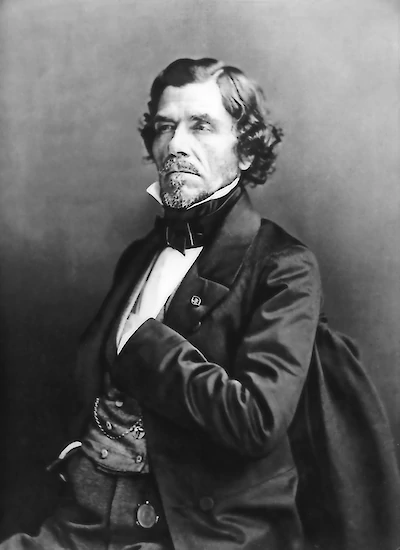

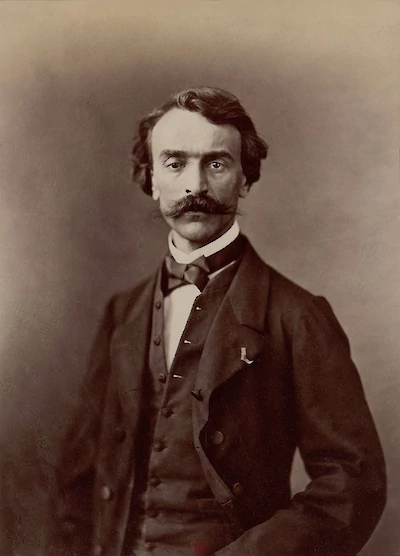

And there is a true documentary spirit to be found in many orientalist works—artists like Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme and Ludwig Deutsch traveled to Morocco, Algiers, Istanbul and Cairo, sometimes staying months or years to fully capture the uniquely stark light and color of these places. The invention of the camera also played an enormous role in the development of orientalist art, allowing artists to document their travels and paint from reference on their return to their European studios.

So why does discussing Orientalist art come with a feeling of foreboding? In 1978, Edward Said, professor of literature at Colombia University, wrote a book that laid bare the discomforting foundation of the Orientalist movement. Simply titled Orientalism, Said’s book is now recognized as one of the foundational texts of postcolonial theory, and it is a brilliant, gnarly read.

The term Orientalism has its roots in the latin word Oriēns, meaning ‘the eastern part of the world’ as opposed to the Occident, or western world. And this dualism is precisely what makes Orientalism such a difficult and problematic movement. Said defines Orientalism as “a way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the Orient’s special place in European Western Experience.” And here is the crux of the issue: Orientalism may look like a depiction of middle eastern and North African cultures, people and landscapes, but Orientalism is a construction of the Western imagination.

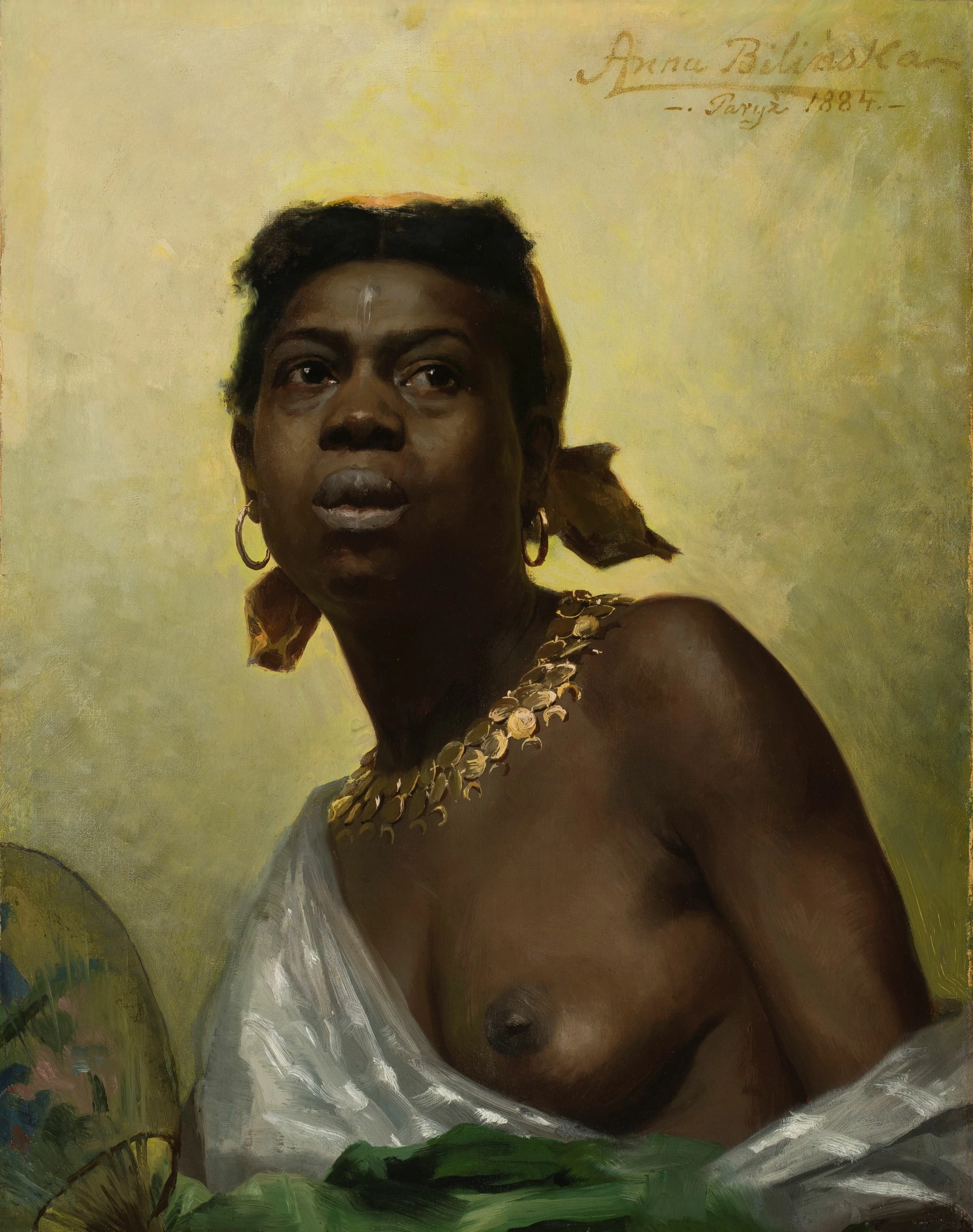

Cultural appropriation is as old as human history, but the orientalist genre is rife with a particularly greedy, exploitative version of appropriation, which Said called a surrogate for underground western desires. Its popular themes read like a playbook of white male fantasies—harems of languid, available women. Slave markets where more young women are bought and sold, and cryptic, unassailable masculinity ruling in splendorous palaces. Said argues that orientalist art is problematic because it is created by artists that, however noble their intentions, are influenced by their vantage point—that of a western observer in an age of predatory colonialism.

This is the contradiction at the heart of orientalist art: Orientalism claims to offer a voyeur’s window into the decadence and exploration of the exotic, sexualized world of the Orient. But Orientalism was never about the Orient, it was a mirror held up to the exploitative fantasies of the western world.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Orientalism? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

Drama, movement and a search for the exotic

1798 – 1863

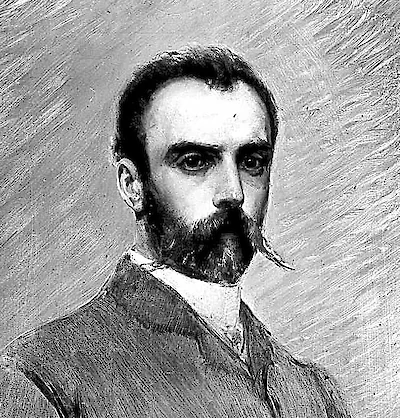

The line between art and sex

1851 – 1896

A merciless teacher trains 2000 young artists

1824 – 1904

Painting in the shadow of a best friend

1836 – 1913

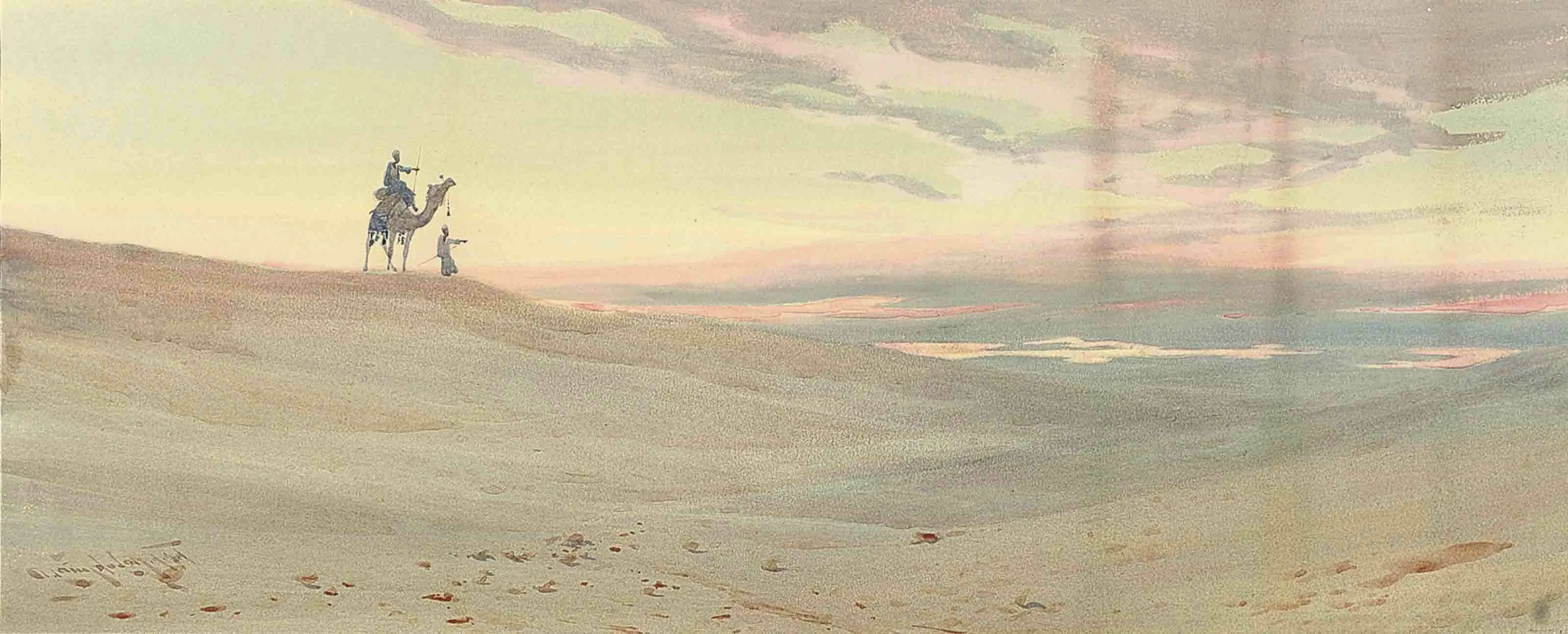

The poetry of sand and sun

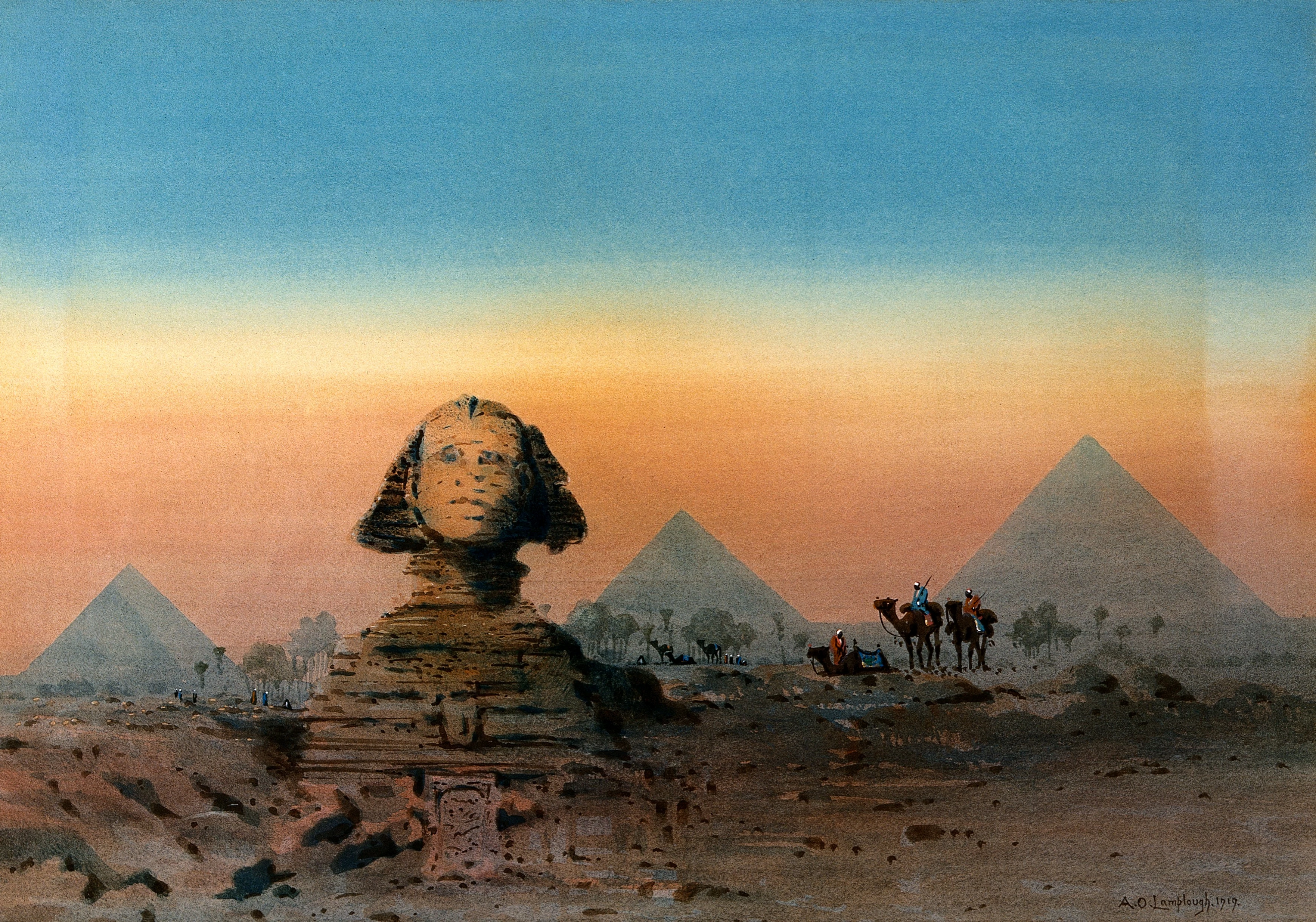

1877 – 1930

Capturing details from 2000 miles away

1855 – 1935