Natürlichekunst, or Natural Art

A few weeks ago I saw my first gongshí in person. Two hours into a rangy wander through the least popular rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and my brain was collapsing. I’d gotten stuck in one those second floor balconies above the greek marbles, consumed by endless rows of uninspired cycladic pottery and votives to pedestrian gods. In the ‘80s a psychiatrist coined the term Stendhal Syndrome to refer to the unique mental exhaustion incurred by long stints of art viewing, and I was feeling it. I was ready to go home. But the Met is a stubborn labyrinth, and though I’ve spent dozens of hours wandering its halls, on this rainy Tuesday I found myself somewhere entirely new to me.

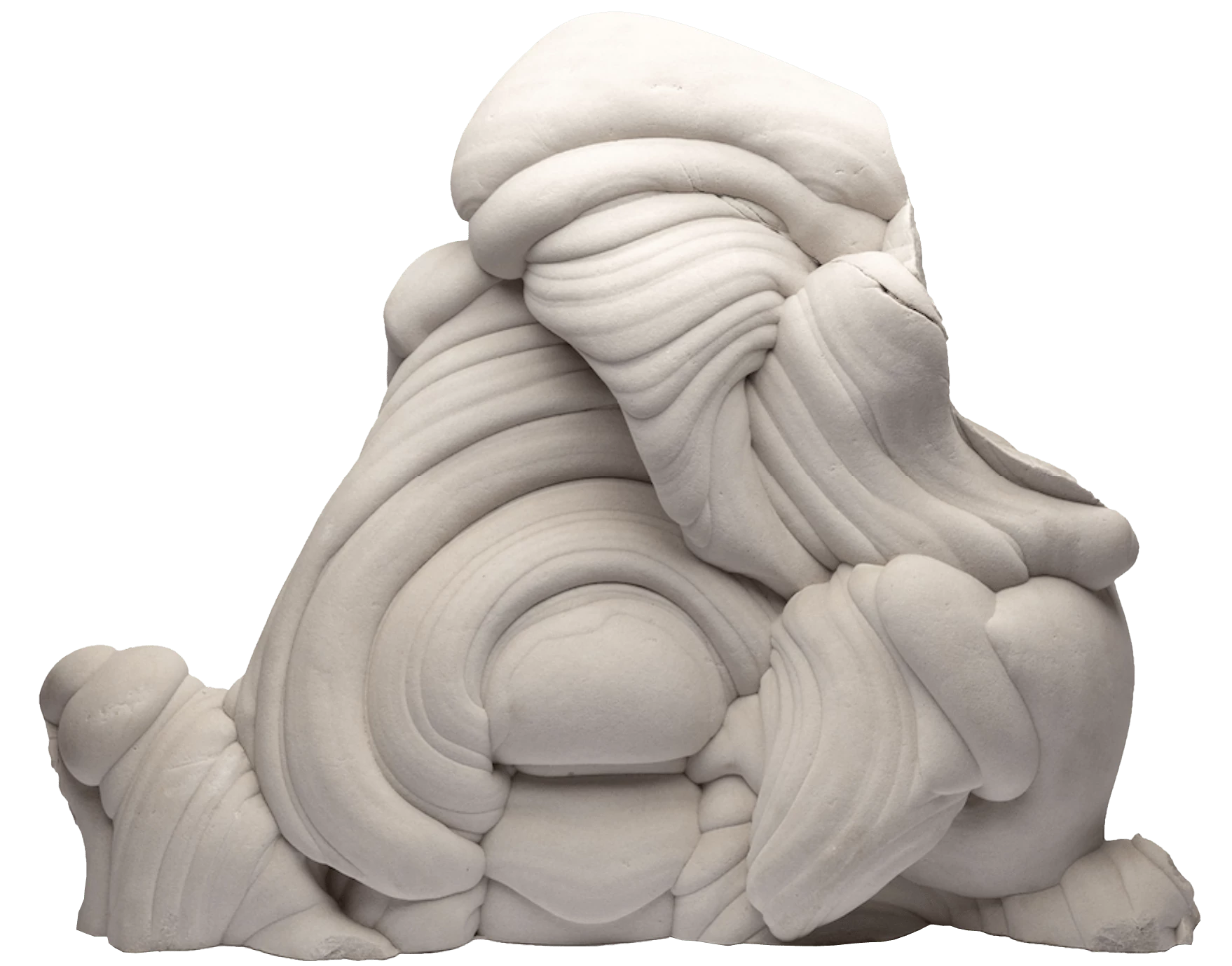

If you’re rich enough, or own a spectacular art collection, you can buy yourself part of a museum and have it filled with your favorite things when you die. Later, I’d learn that I had stumbled into the sarcophagus of one Richard Rosenblum, sculptor, dead in 2000, whose collection of asian art was gifted to the Met on the ambitious stipulation that traditional craftsmen transform an entire room into a Chinese Scholar’s garden—all I knew was that I was staring at a rock as tall as me, and I was certain it returned my gaze.

…

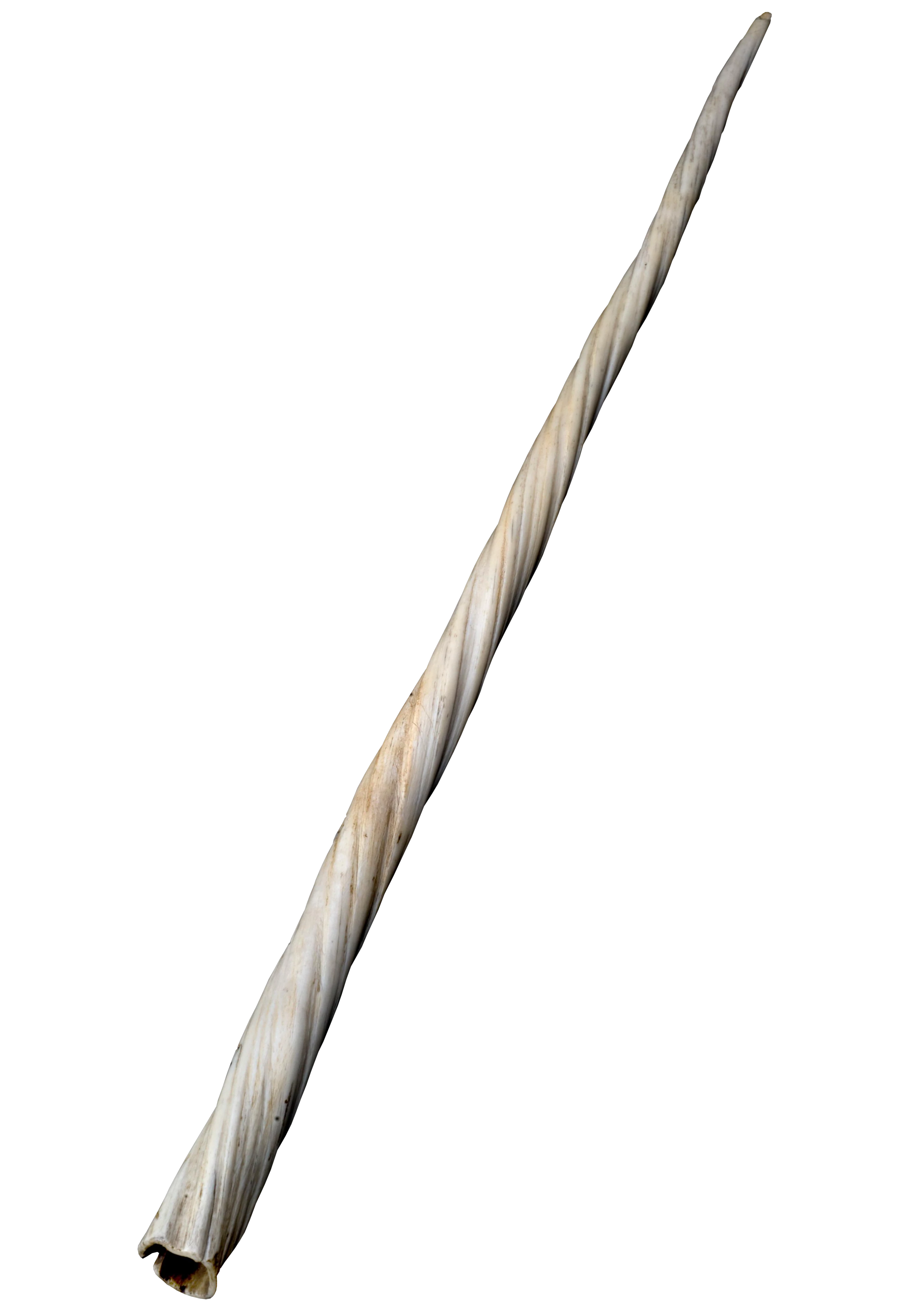

I’ve now bought books on scholar’s stones, written about them, and even had a craggy piece of volcanic Ba Yin mountain stone shipped in from Guangxi, mounted on traditional rosewood by someone I know only as “Riversoul.” I’m legitimately obsessed by the things, but they’ve also left me with a question I can’t shake: why had I never seen a natural object, untouched by human hands, displayed in an art museum, until I blundered into the Rosenblum room?

There are places where nature is displayed with varying degrees of veneration. Specimens of flora and fauna haunt the dark halls of Natural History museums around the country, the pinned corpses of rare butterflies are traded on Etsy, and my mother-in-law collects heart-shaped stones to give to her grandchildren. But I’m not talking about objects we collect as a hobby or out of scientific interest, I’m talking about the careful presentation and intensional, specific aesthetic consideration that we reserve for a masterful painting or a sublimely rendered sculpture.

I suspect it’s a poverty of western culture that we don’t seem to see nature this way. The aesthetic, poetic and spiritual contemplation of stones and interspecies collaborations like bonsai has flourished for the last thousand years in China, Japan, and Korea in resonance with Zen Buddhist and Shinto principles. Taking time to give nature your full attention is part of the deal. I also wonder if language is part of the issue. Since its earliest days in China, the art of stone appreciation has had vocabulary, grammar, and unique metaphors. In the west, it’s all lumped into “collecting” with the term’s strange focus on quantity and completion. Even there, if you collect man-made objects you might be a philatelist or practice phillumeny but collect natural objects and at best you might be a rockhound or beachcomber.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Natürlichekunst, or Natural Art? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.