In 1967 the UCLA professor of psychology Albert Mehrabian claimed that 55 percent of human communication is through body language alone. It’s an often misquoted study, but the idea that posture means something is undeniably true. And unsurprisingly, the ancient Greeks got there first.

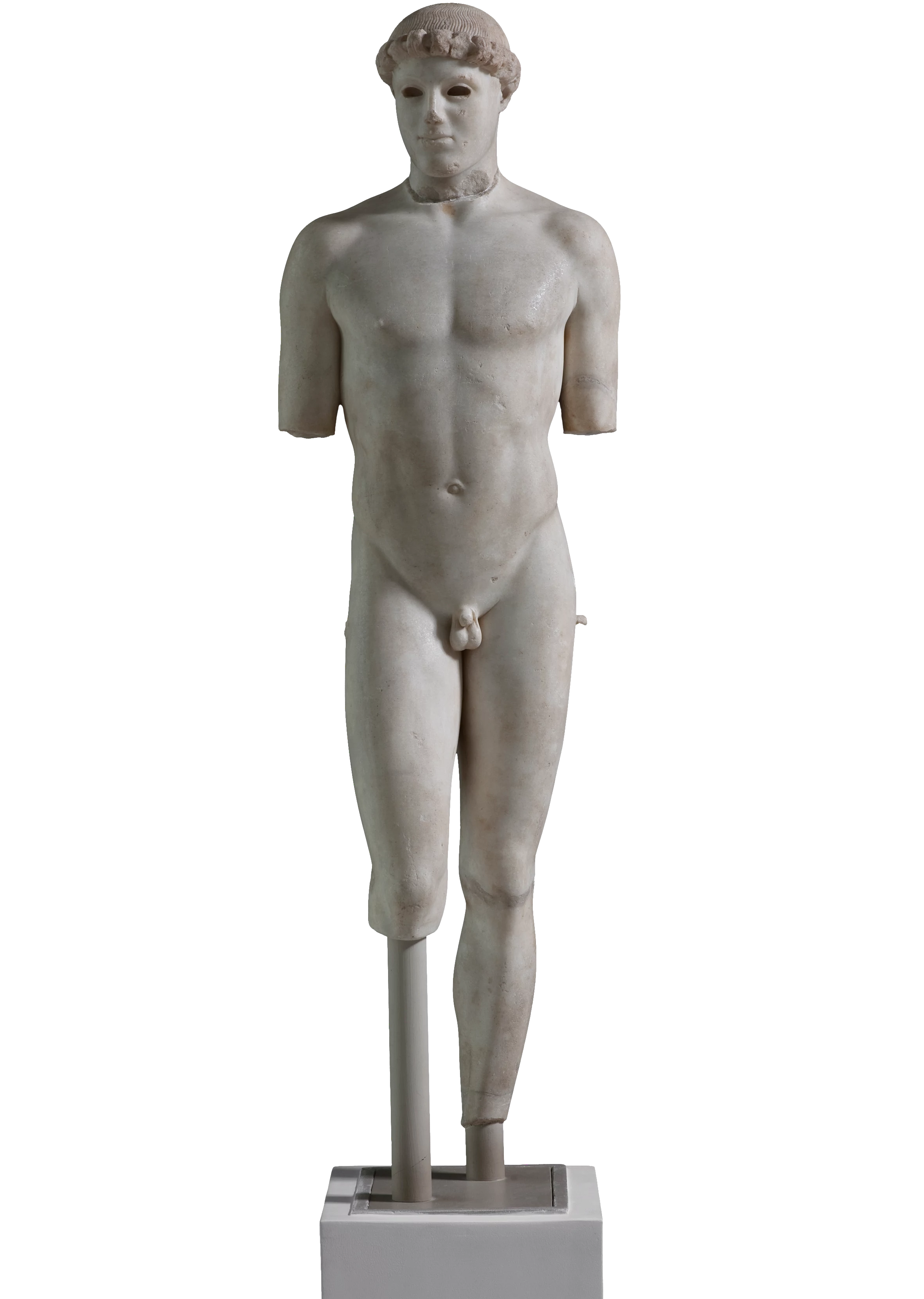

Up until the 5th century BCE, when the human form was immortalized in three dimensional sculpture it was a profoundly formal affair. The Mediterranean standard was the kouros (male) and the kore (female) motifs, stiff, forward-facing youths in a style similar to rigid Egyptian depictions of gods and rulers. These forms aimed to elevate the human form to divine status, symmetrical and perfect, but also stripped these bodies of what makes us most human—angles of repose.

The first artist to break this rigid mold, based on the relatively scarce surviving examples, was Kritios, one of a long line of sculptors working in the Attica peninsula, home to the great Greek city of Athens and its surroundings. Kritios was commissioned to create a set of replacement statues featuring the Tyrannicides, a pair of male lovers who paved the way for Athenian democracy, after the originals had been pillaged during the Greco-Persian war. But Kritios took a different approach than the previous artist, rendering his figures with a naturalism previously known in western art. The nuance began, as it often does, in the pelvis.

Traditional sculptural forms set the pelvis and axial skeleton at a firm right-angle to the vertical line of the statue. Flat and even. But Kritios recognized the expressive potential of the angle, and tilted the hip of the statue we now know as Kritios Boy, bending his knee, and by extension canting the entire form from the spine to the shoulders to the position of the arms and head, into a more natural, and more expressive posture. With a single twist of the body Kritios changed the next two thousand years of art history.

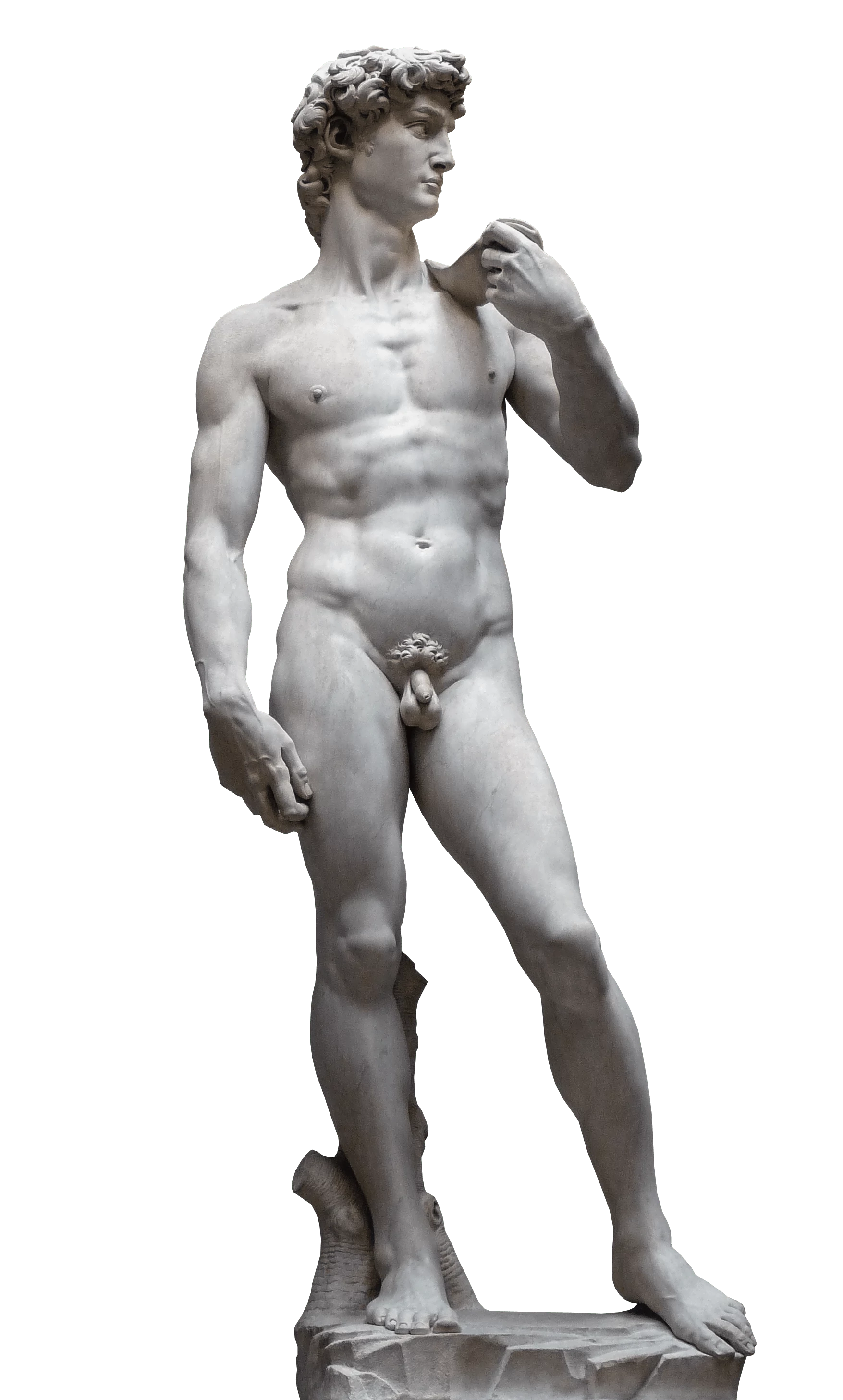

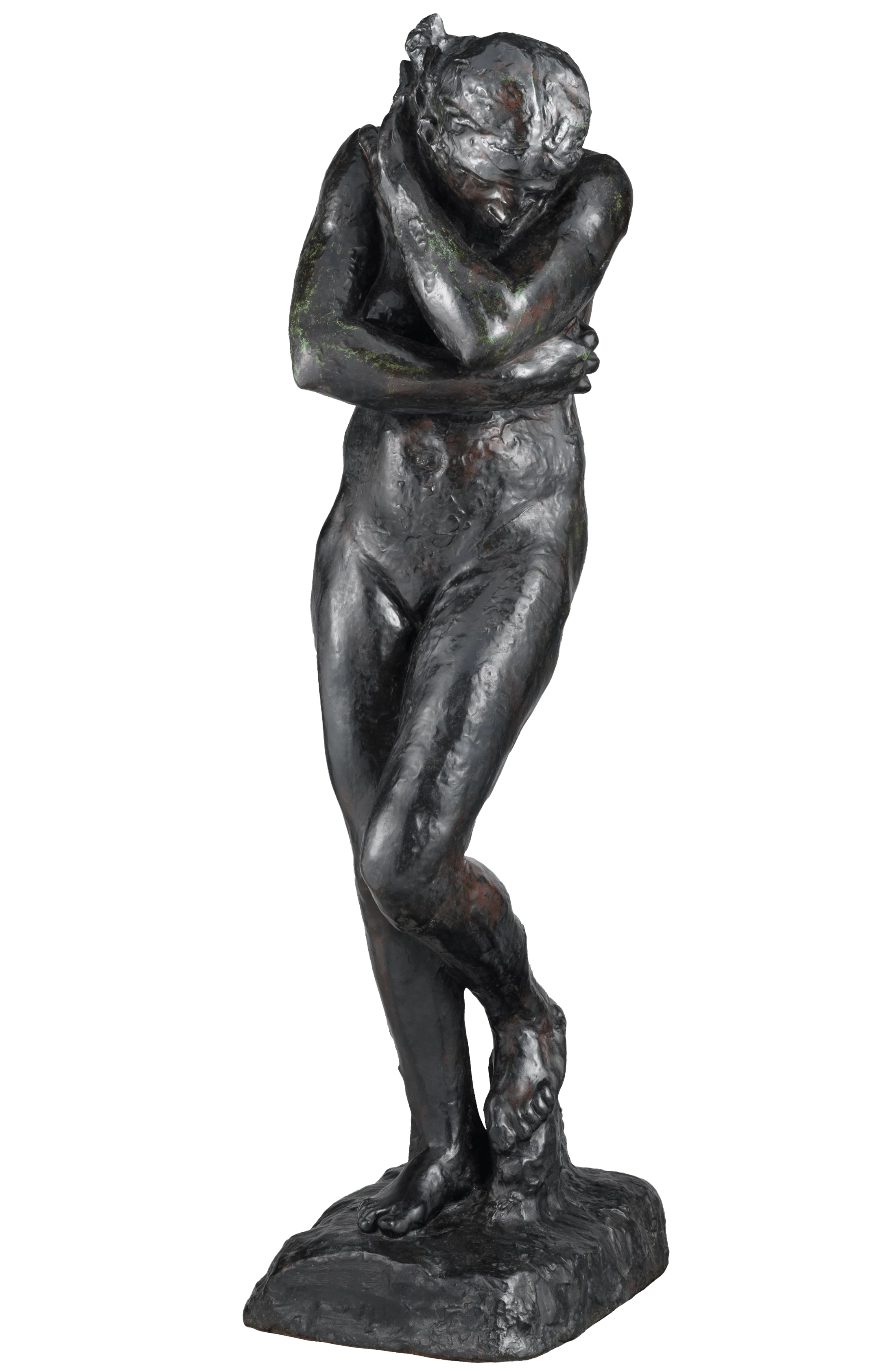

The dynamism, motion, and postures of more natural repose that emerged from Kritios’s slant is known today as Contrapposto, from the Italian “counterpoise.” And believe me, it is everywhere. If you want to spot a contrapposto posture, look at the legs. One leg will carry the weight of the body-this is the engaged leg. The other leg will be relaxed, often bent at the knee, the free leg. Is this actually the way that normal people stand? Not necessarily. The contrapposto posture is a supernormal stimulus, an exaggeration of something normal that triggers an empathic feeling in the viewer. Contrapposto doesn’t just look relaxed, it makes you feel relaxed.

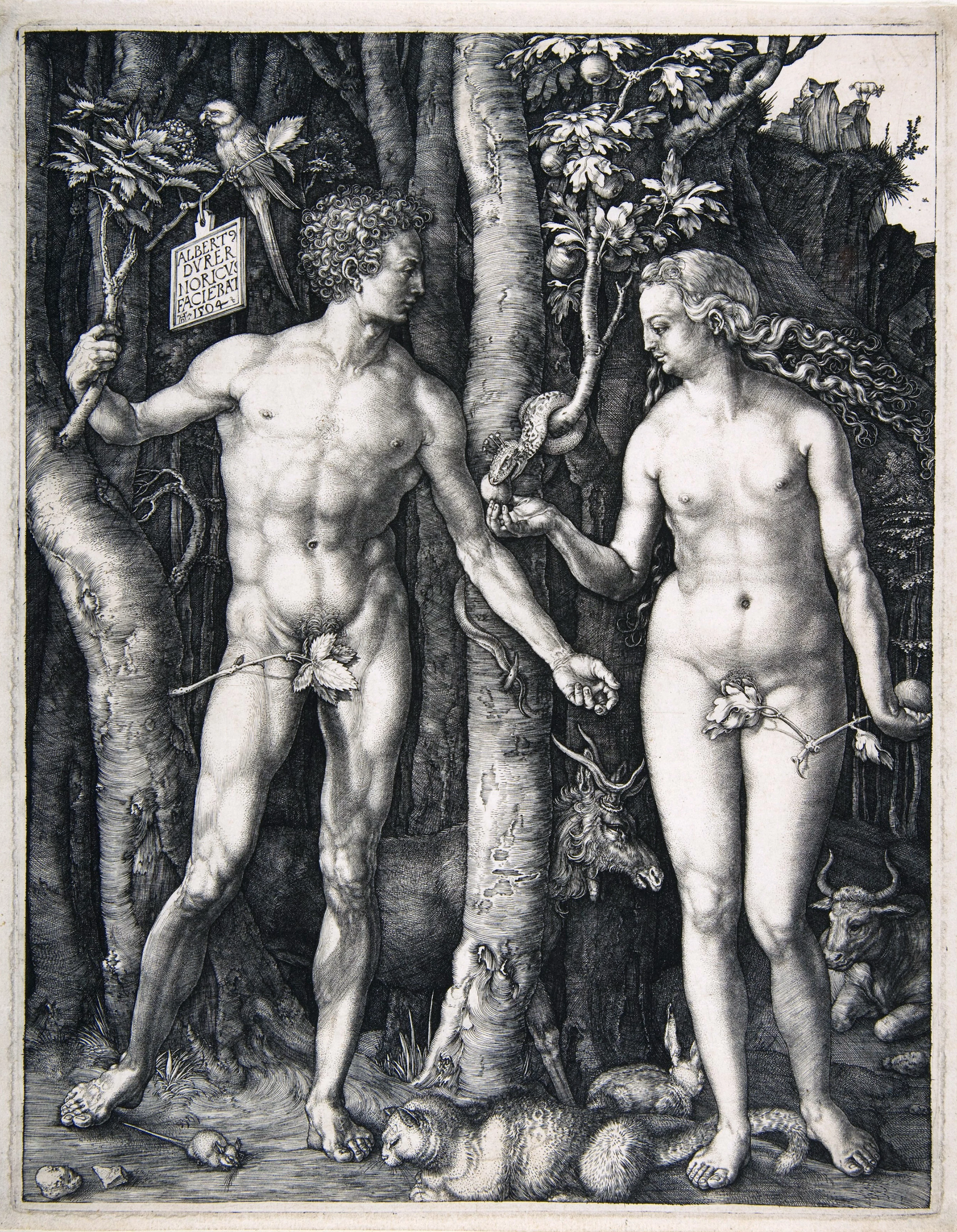

Back to the history, the Kritios boy made a big splash with his contrapposto and continues to, our boy Kenneth Clark called it “the first beautiful nude in art” which is pretty generous, but once humanized, sculptural posture could not be unhumanized (except during the Byzantine era which loved their fridge divine). To look for the contrapposto in post-renaissance work is to look at basically everything. From Michelangelo’s David to Calvin Klein underwear ads, contrapposto has been the rule, not the exception.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Contrapposto? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.