Dada

Dada is anti-dada!

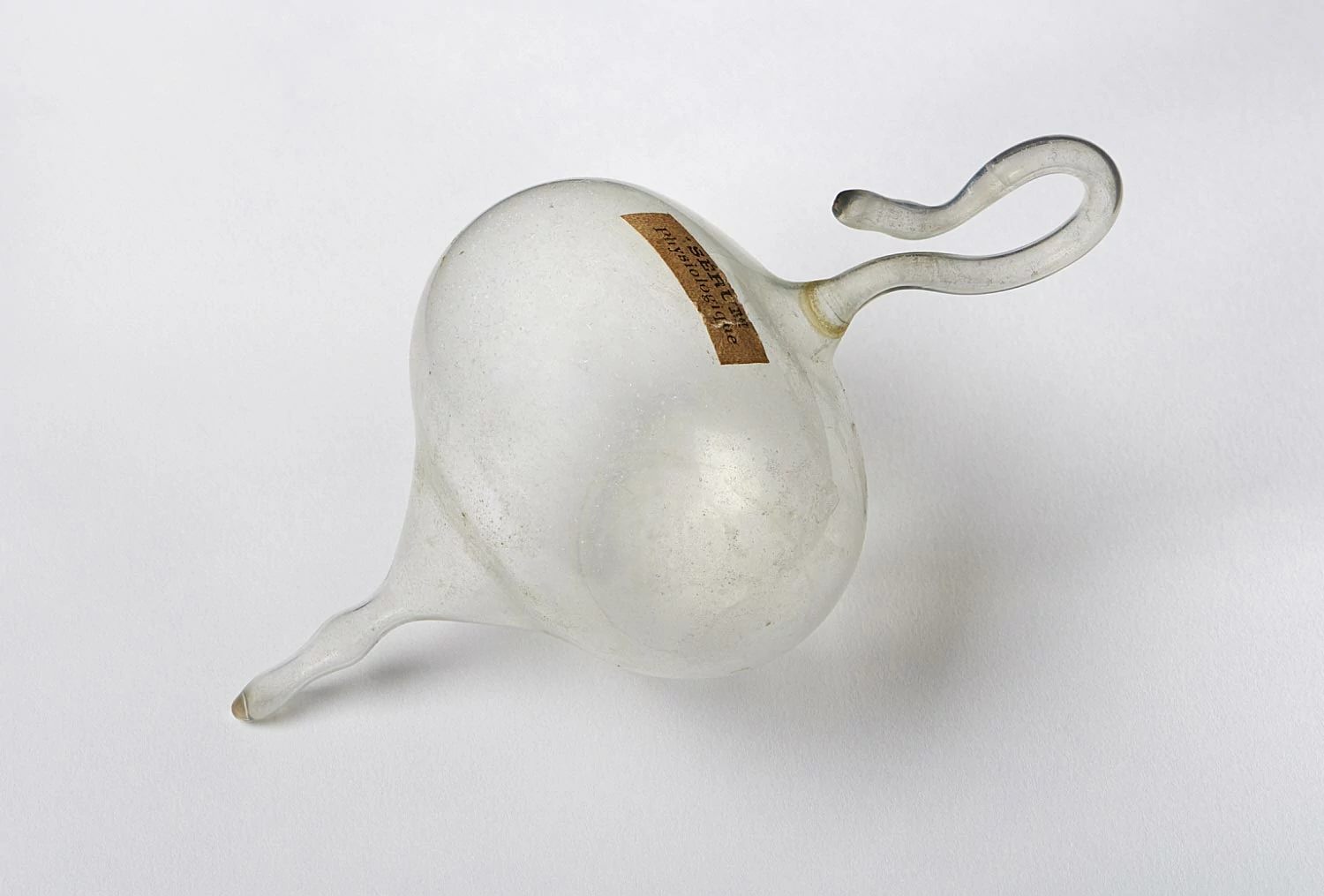

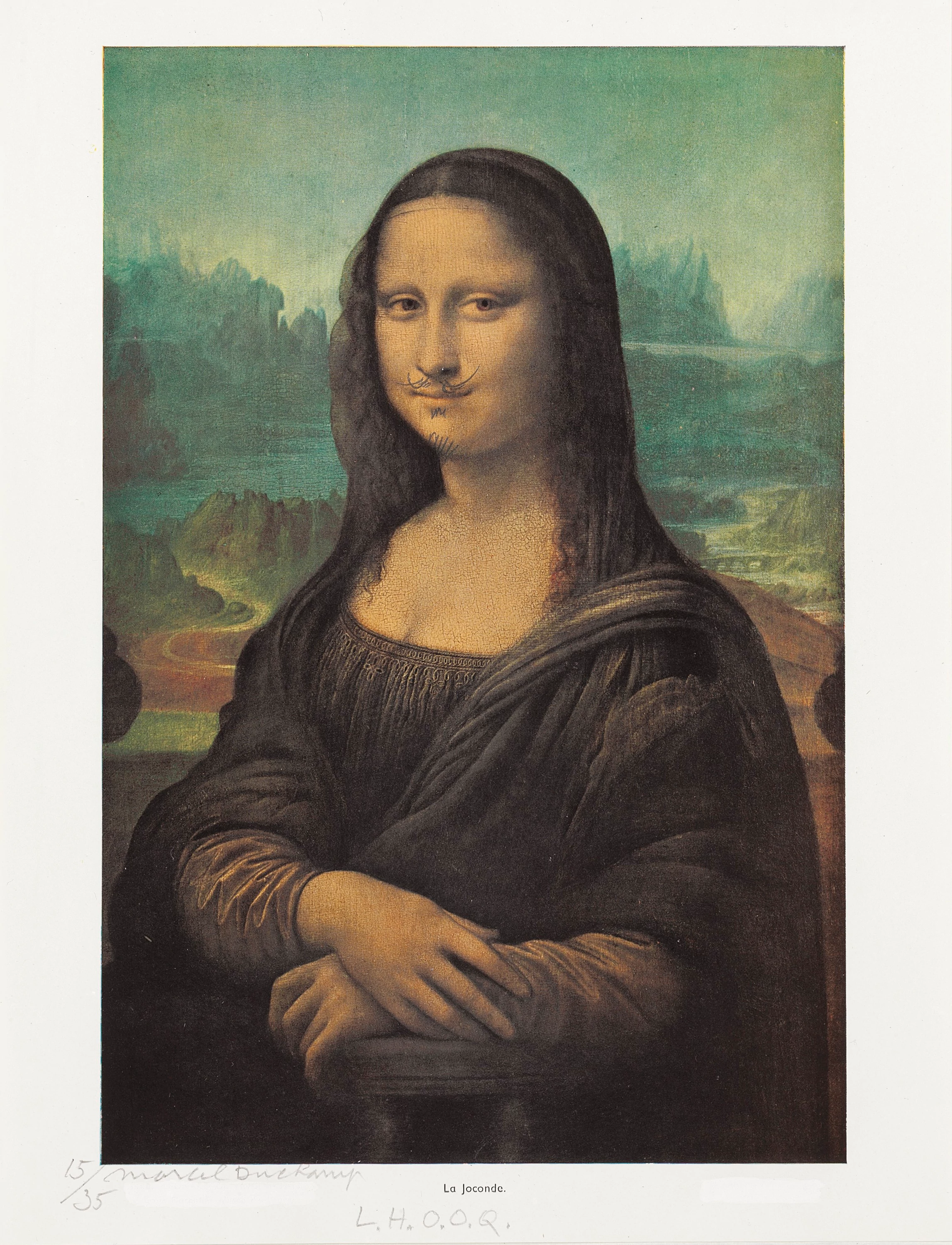

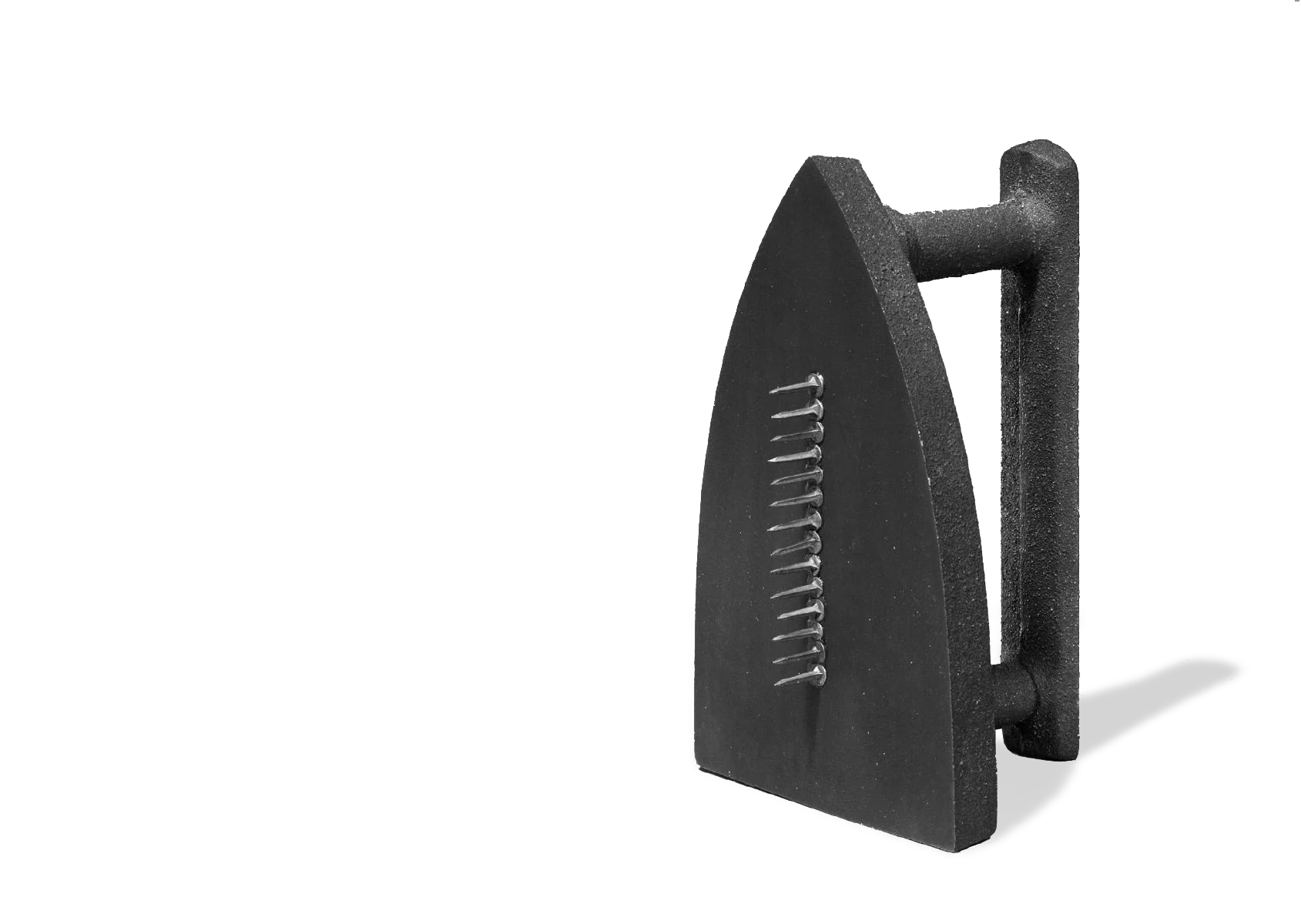

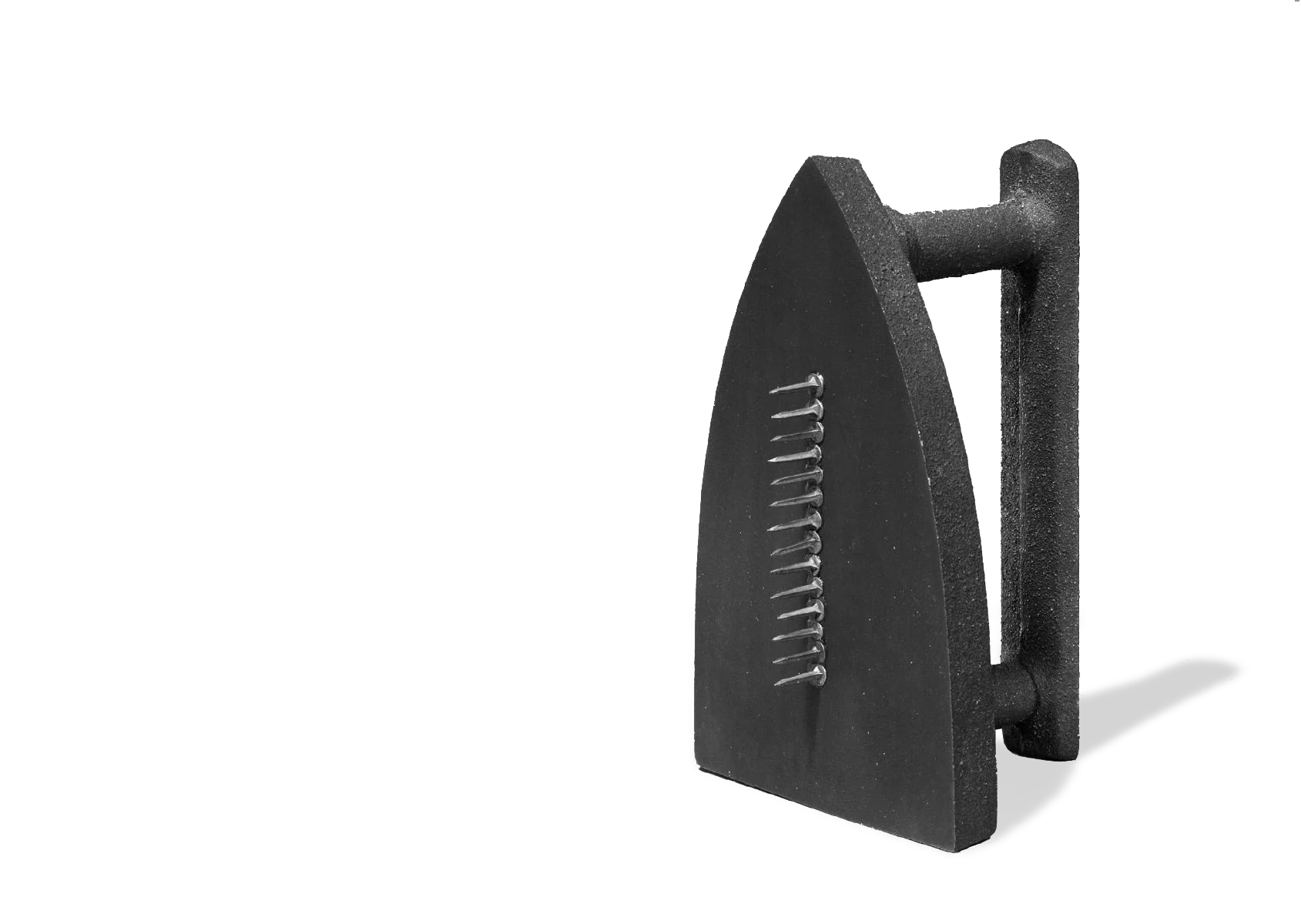

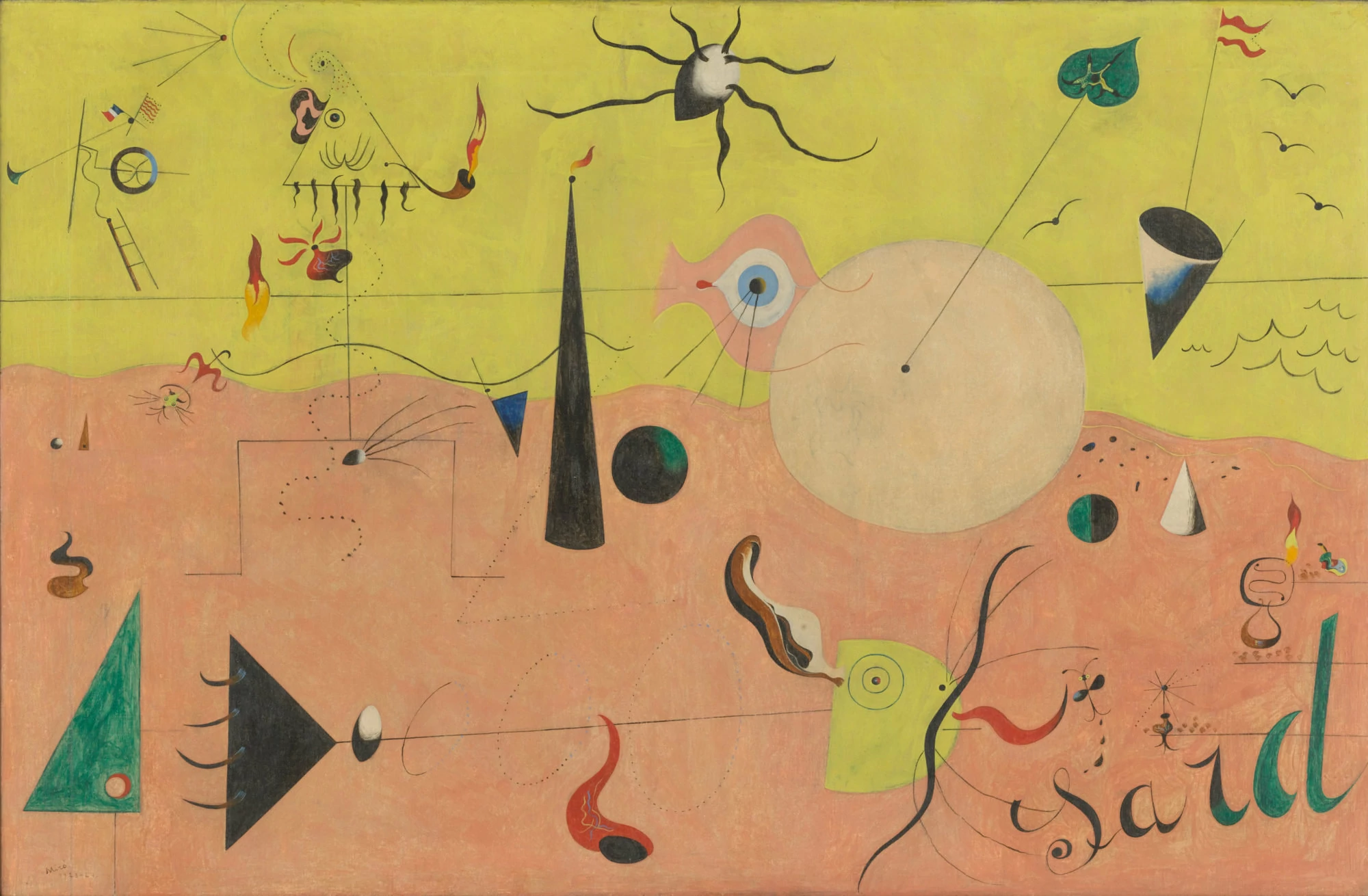

Is it possible to be anti-everything? The Dadaists would shout Yes! then light you on fire. Dadaist art is funny, ugly, and aggressively subversive. You’ve seen Dada even if you didn’t know it. Mona Lisa with a mustache? Dada. A toilet on a pedestal? Dada. But the movement went further. In the early 20th century, Dadaists caused riots and called it art, bought homegoods from hardware stores and called it art, and threw together collages by chance and called it art. The Dadaists hoped to destroy the traditional values of art—but why?

In 1916, the world was in the brutal throes of World War 1. Bloodshed and death spanned Europe in one of history’s most lethal and pointless conflicts, and in the center of the milieu was Zurich. Switzerland famously remained neutral during The Great War, and in that relative stability a handful of artists asked how art could possibly still matter in a world on fire. Dada began here, when the German artist and writer Hugo Ball created the Cabaret Voltaire, a collaborative art venue in the back room of a dirty bar. Artists, poets, and playwrights flocked to the new space, and in July of 2016, Ball stood up before the group and read a manifesto, declaring a new movement with an international name:

In French it means “hobby horse.” In German it means “good-bye,” ... In Romanian: “Yes, indeed, you are right” … An International word. Just a word, and the word a movement.

The word was Dada, and it became a rallying cry. Anti-war, and anti-art. The world that spawned WWI had also created traditional art, so the Dadaists called for the destruction of both. Romanian artist Marcel Janco summed it up, saying “We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished...public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order...We would begin again after the tabula rasa (clean slate).”

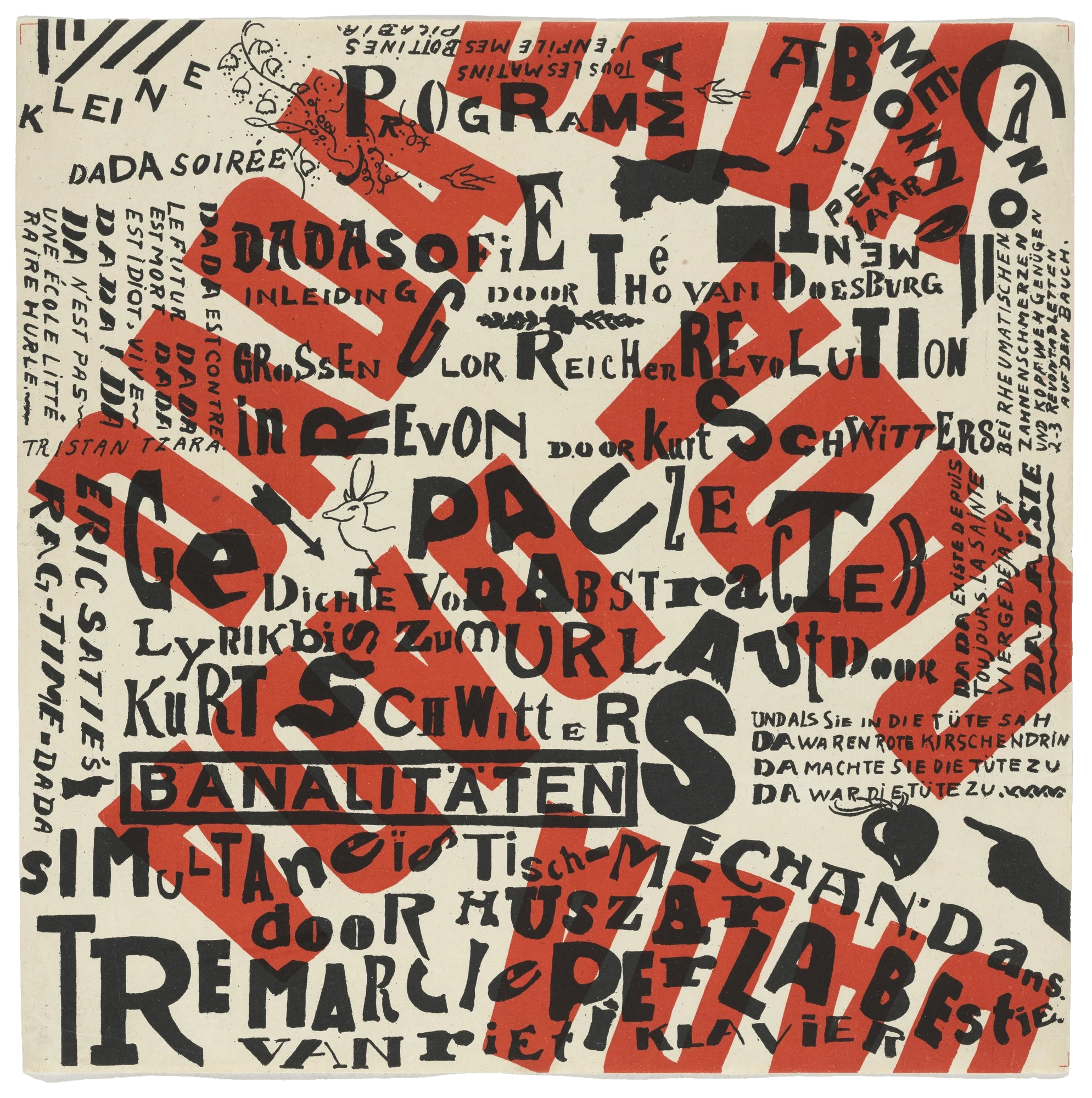

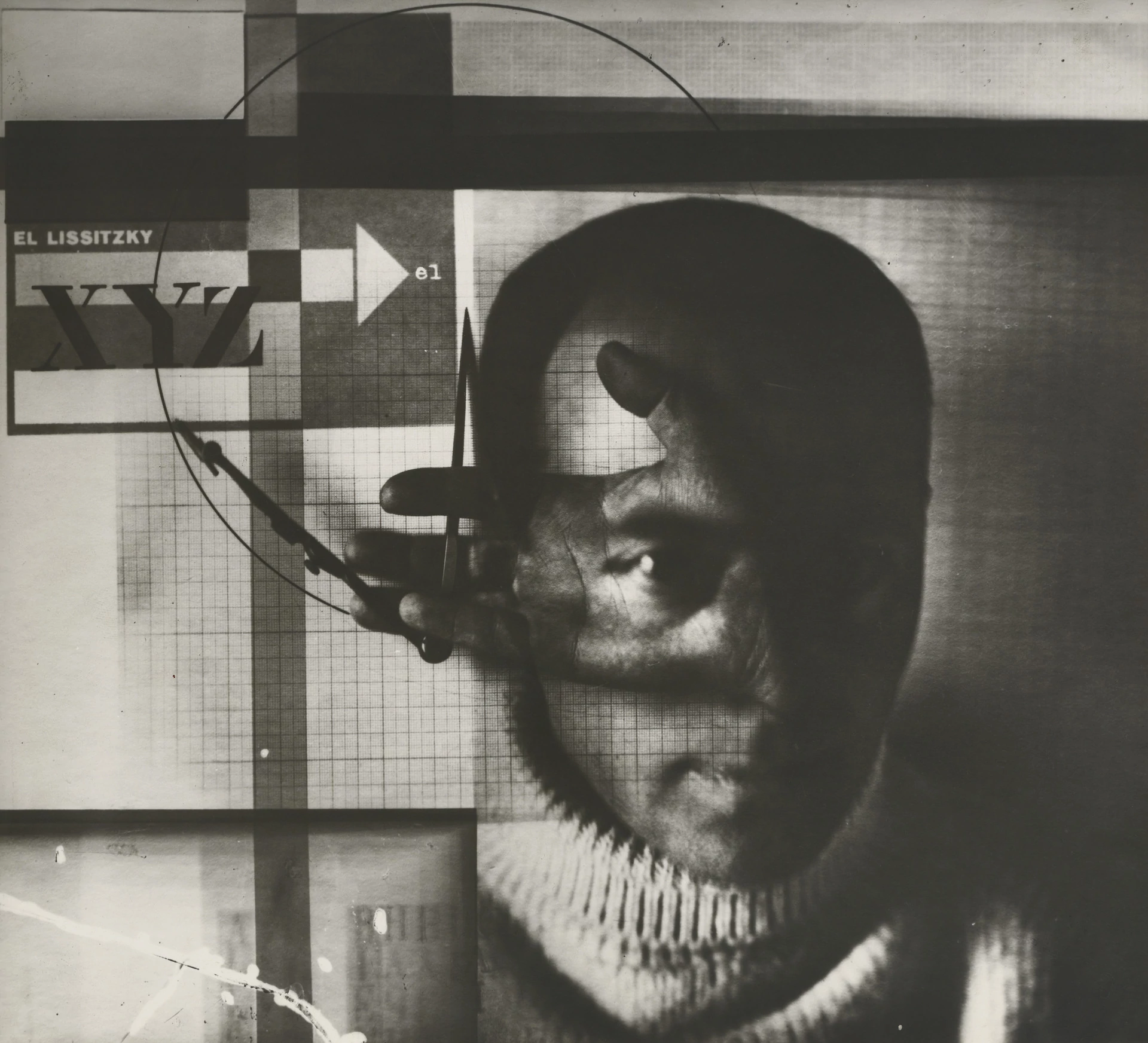

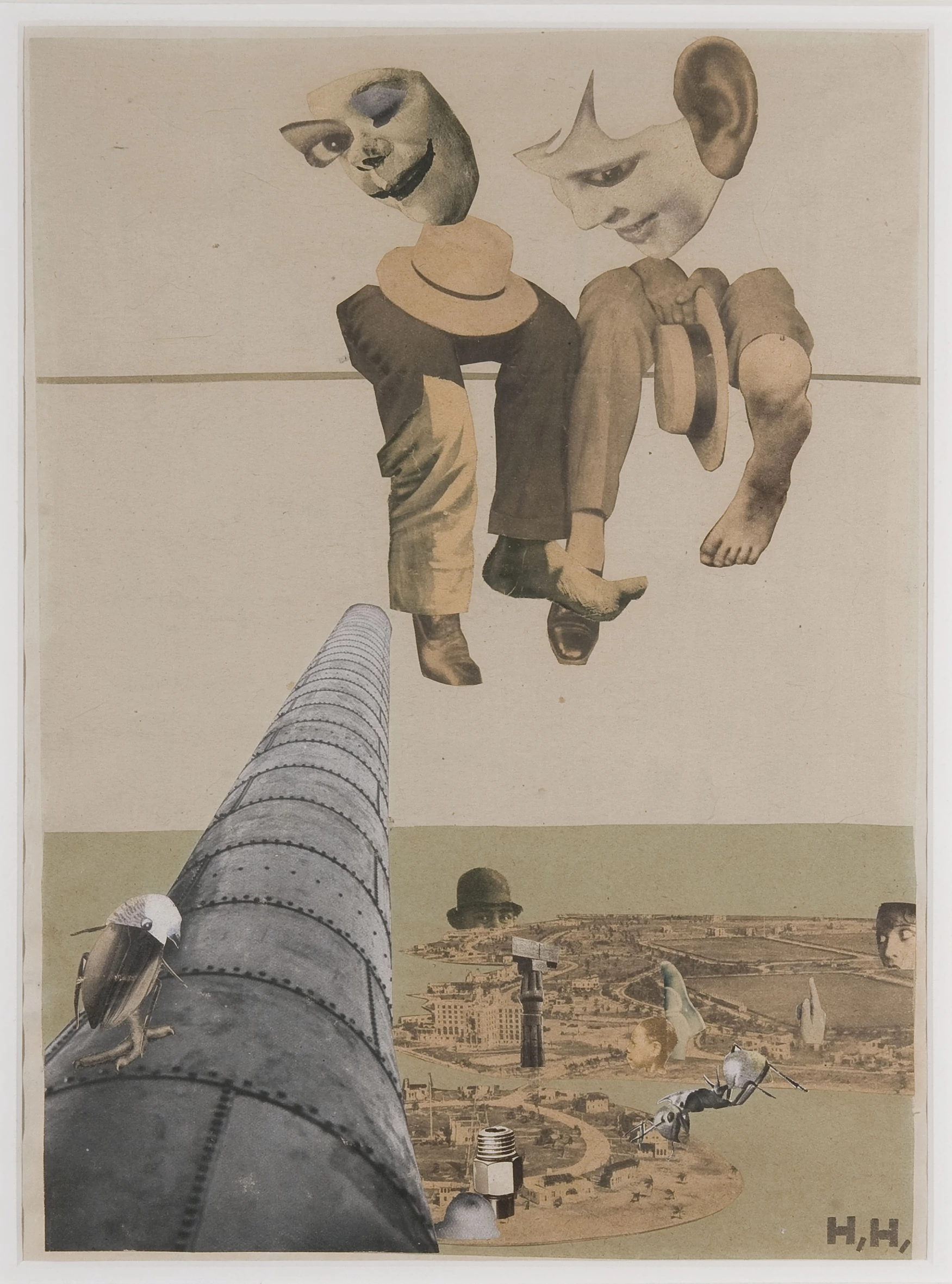

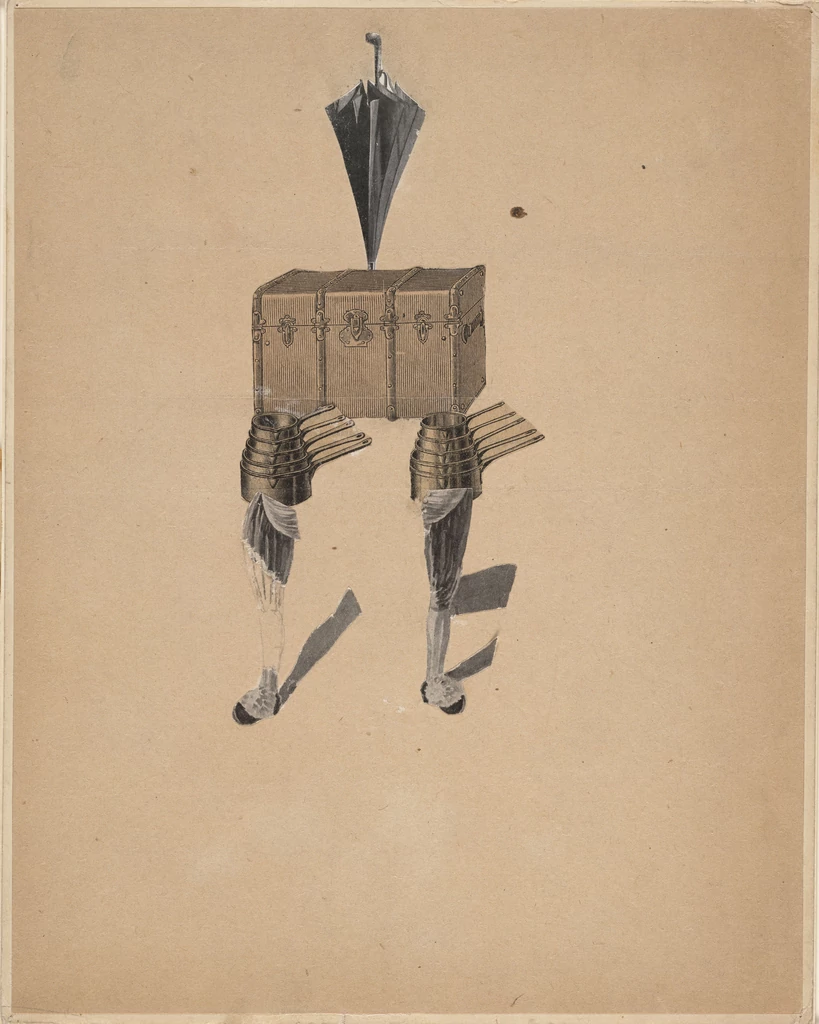

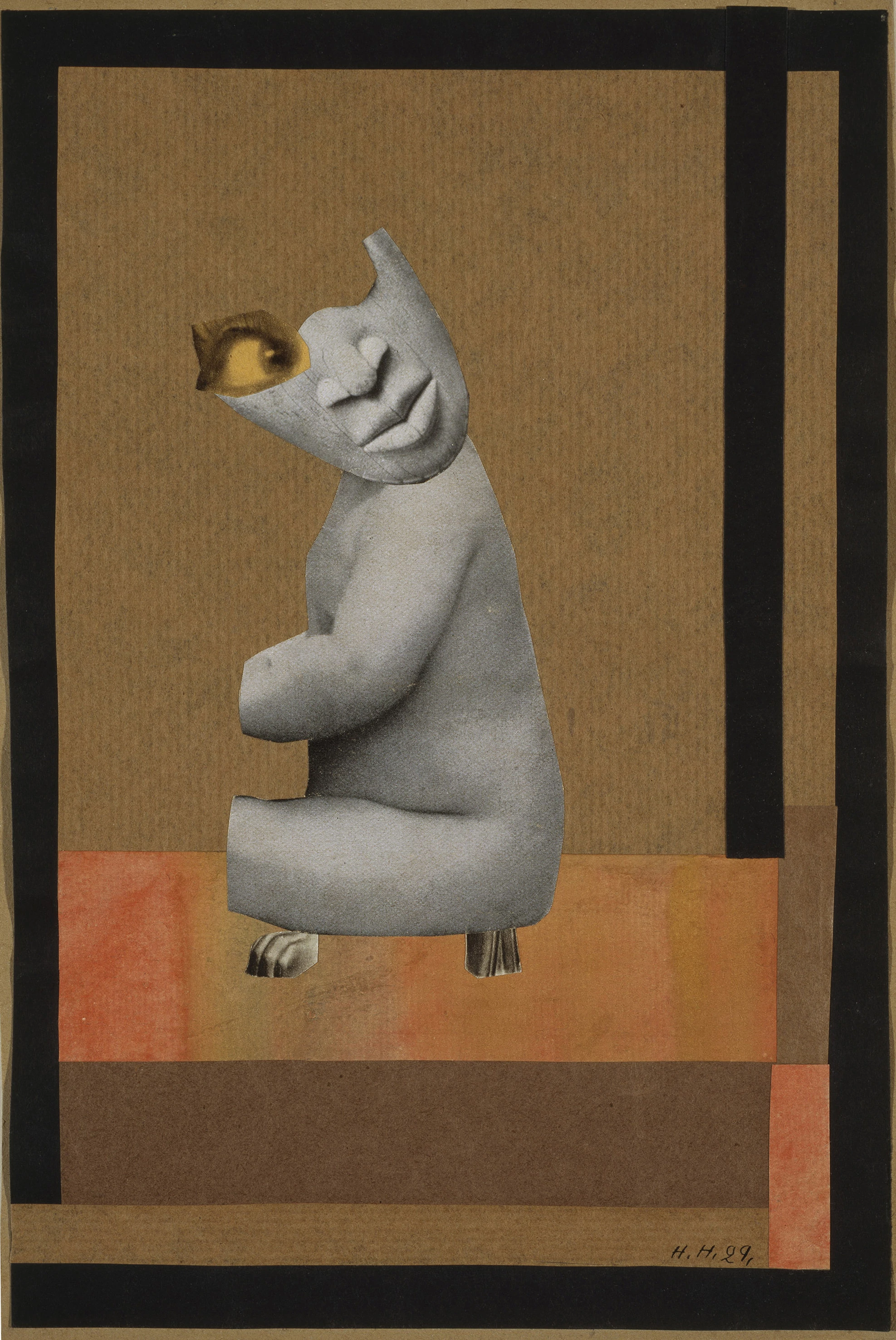

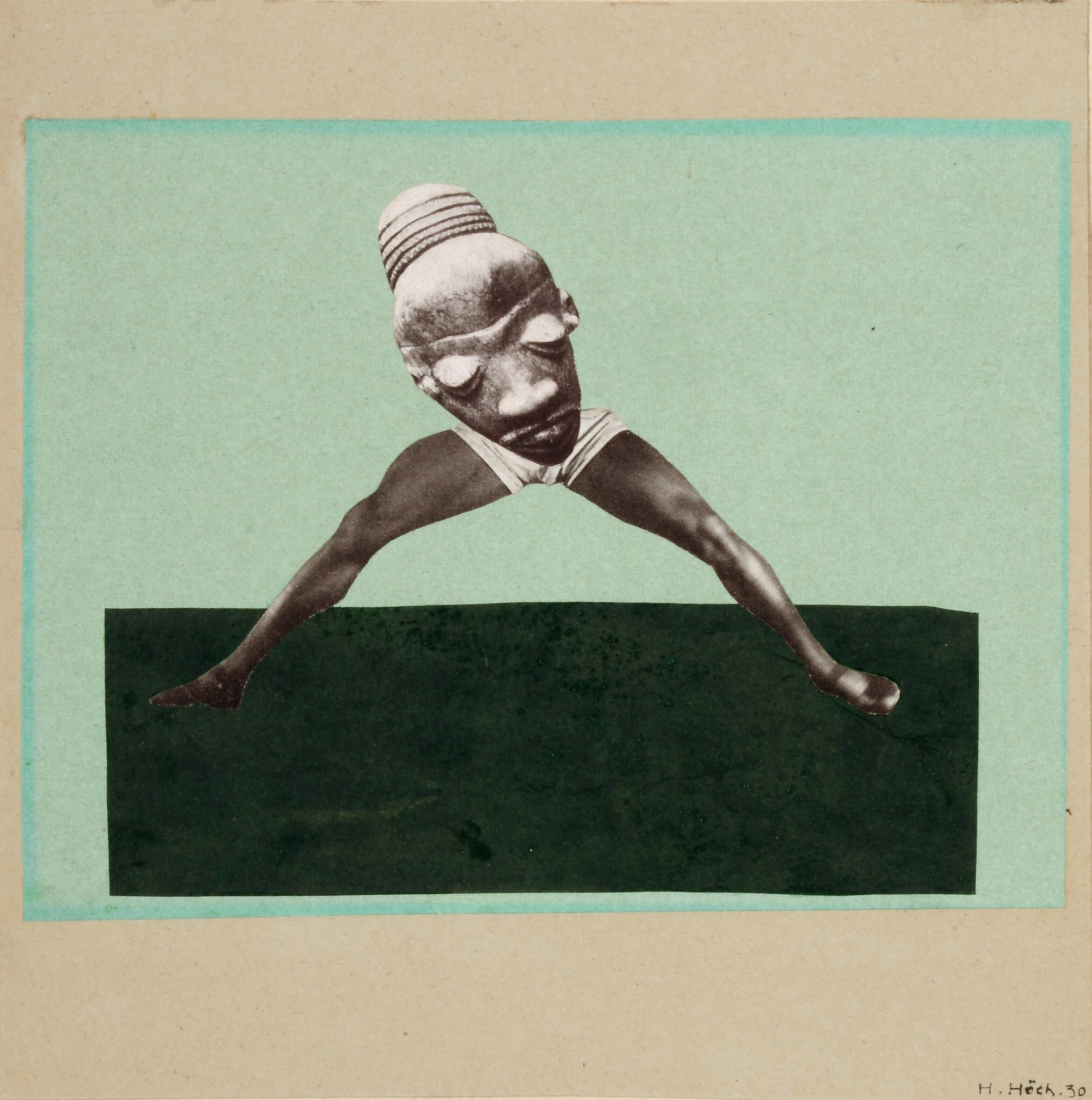

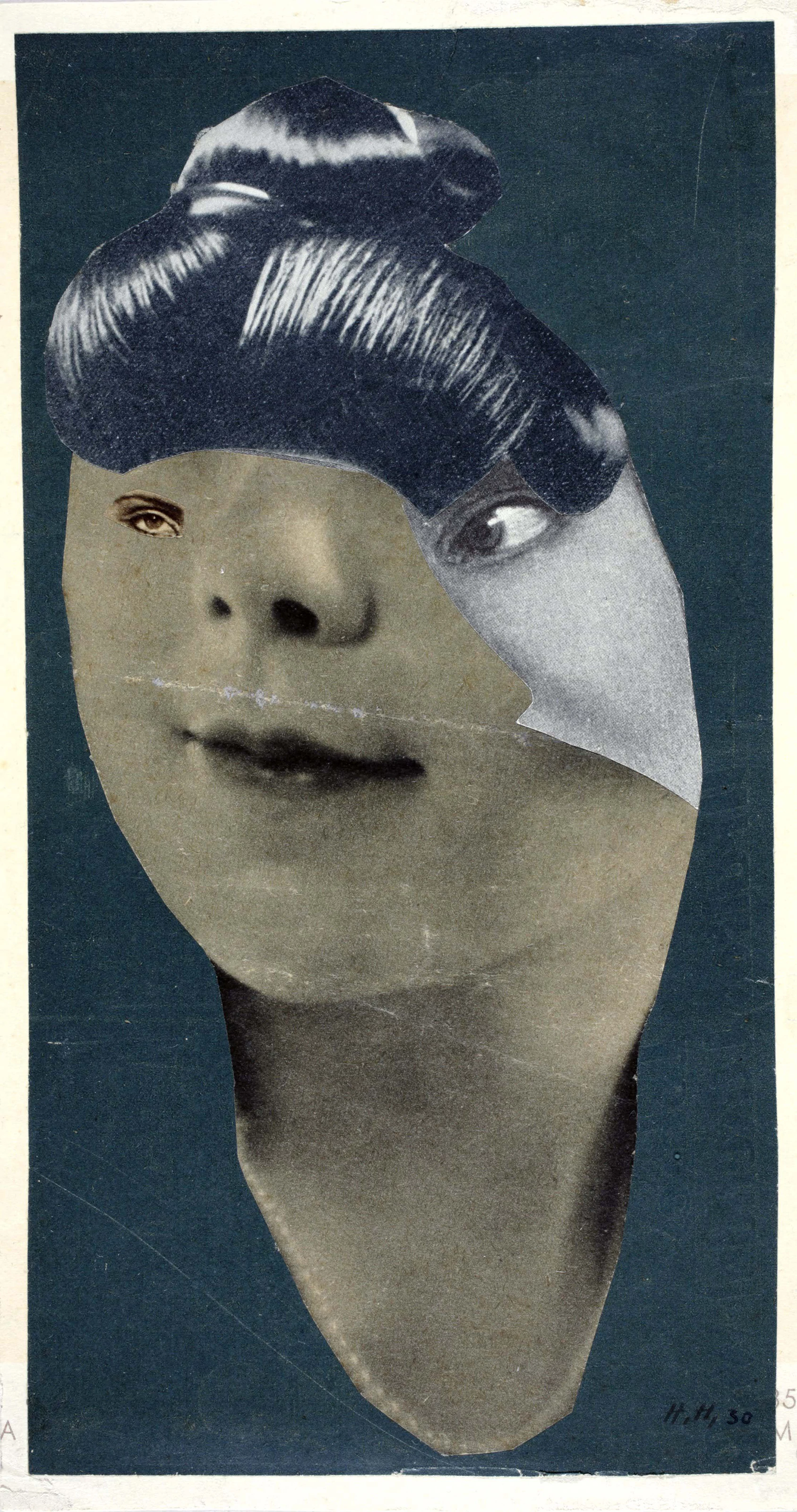

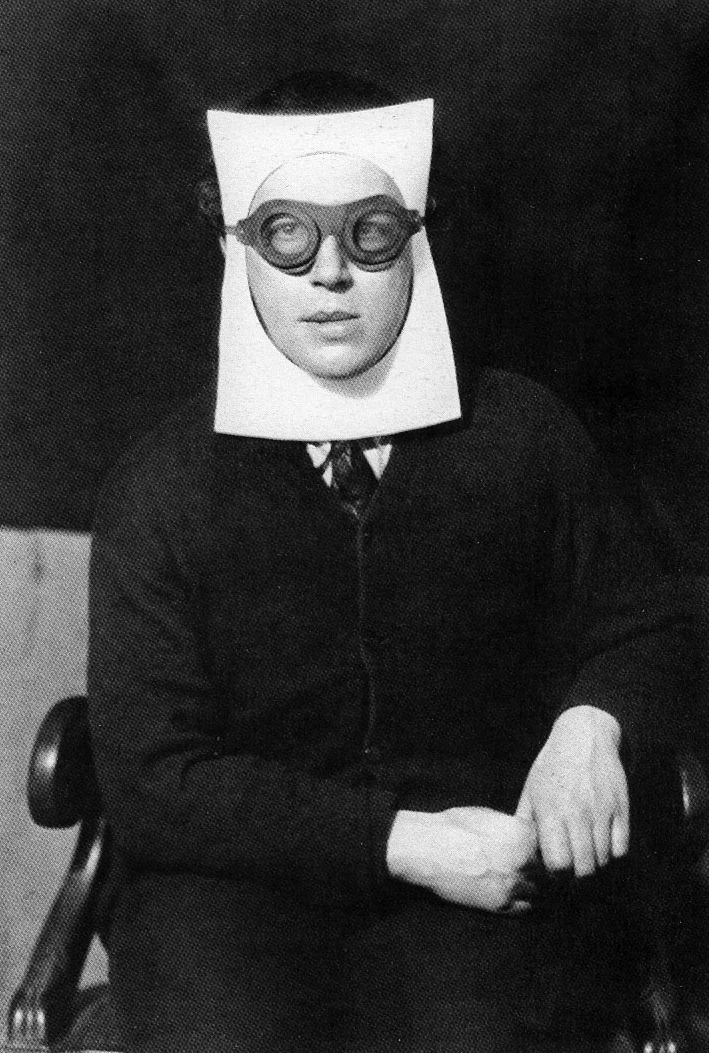

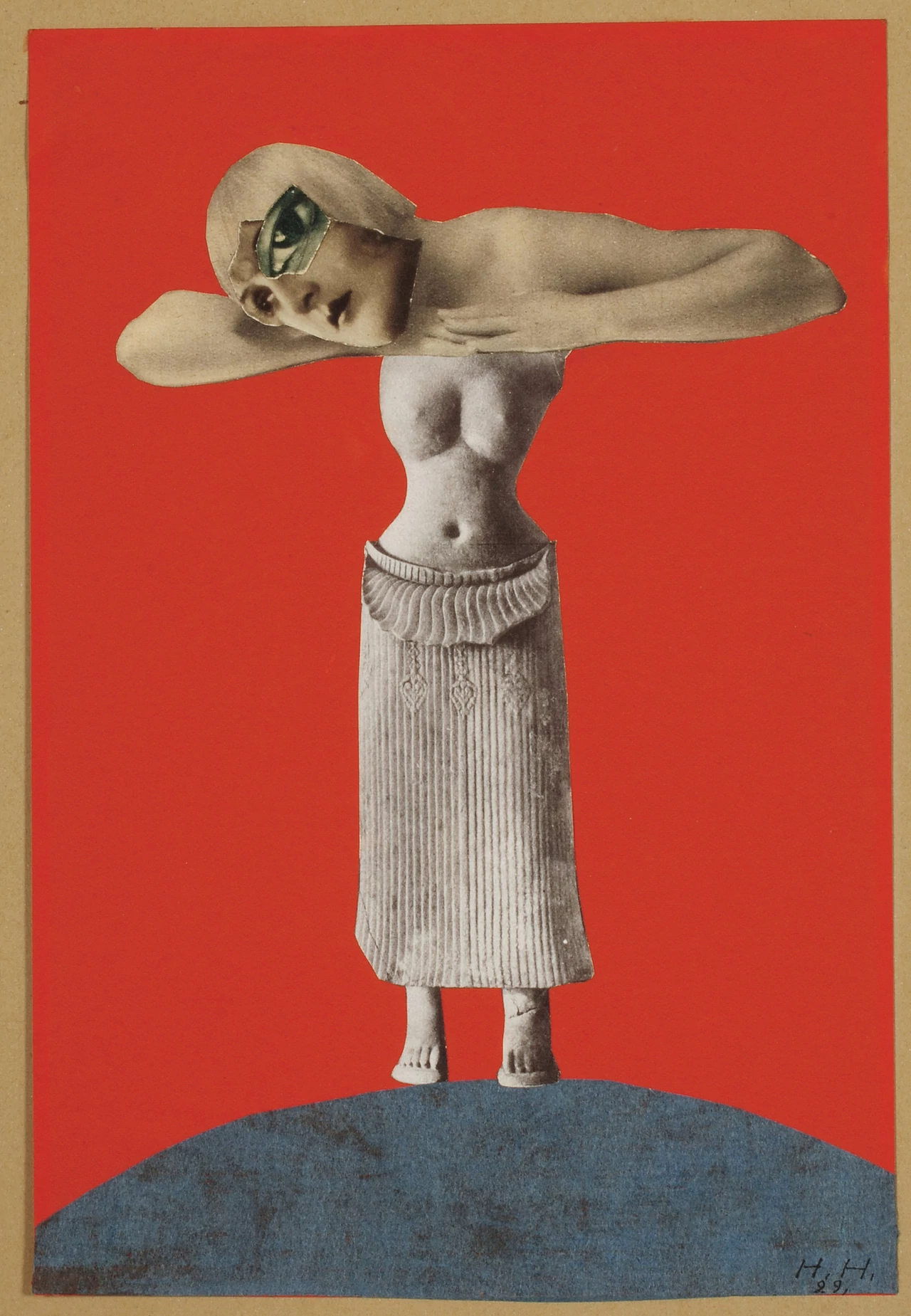

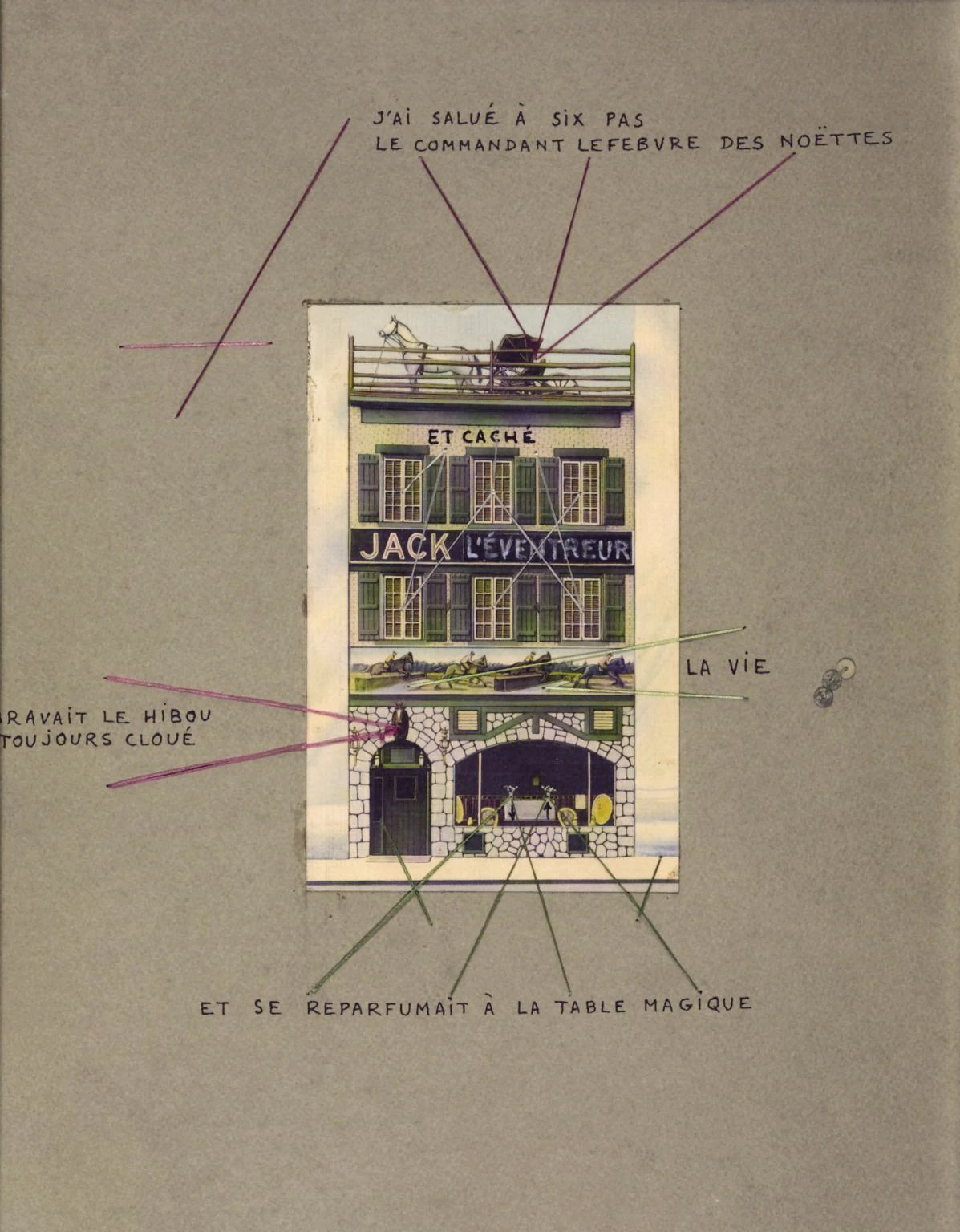

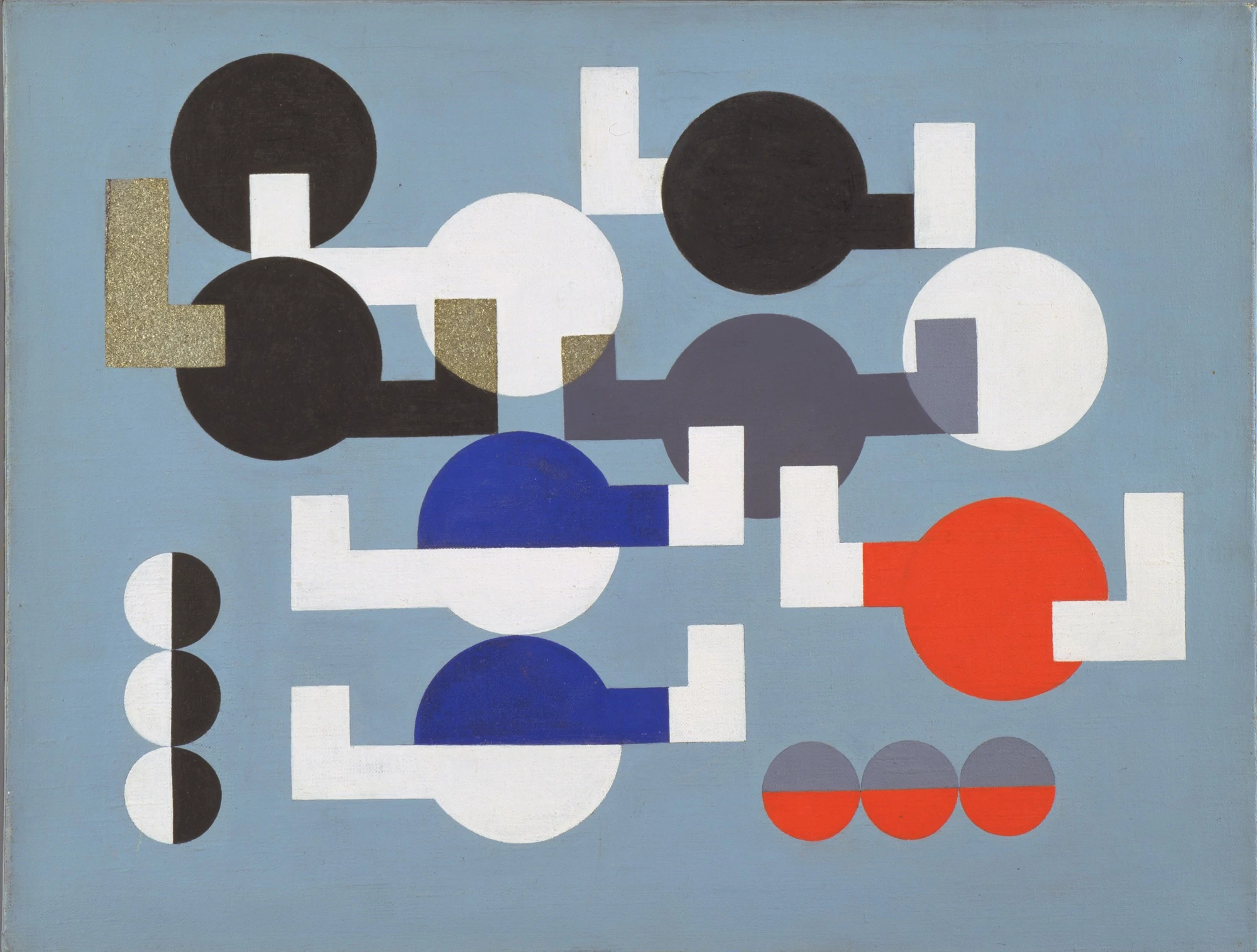

In 1917 Hugo Ball moved to Bern, Switzerland, leaving the Zurich Dadaists in the hands of the poet Tristan Tzara, who wrote a second Dada Manifesto and began evangelizing the movement via letters and manifestos to artists in France, Italy and Germany. At the climax of WWI, Dadaism caught fire in Berlin, where Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann created collages from dismembered magazine clippings and held frenzied lectures and performances. In Paris, Dada’s political heat captured the imagination of André Breton, who later founded Surrealism.

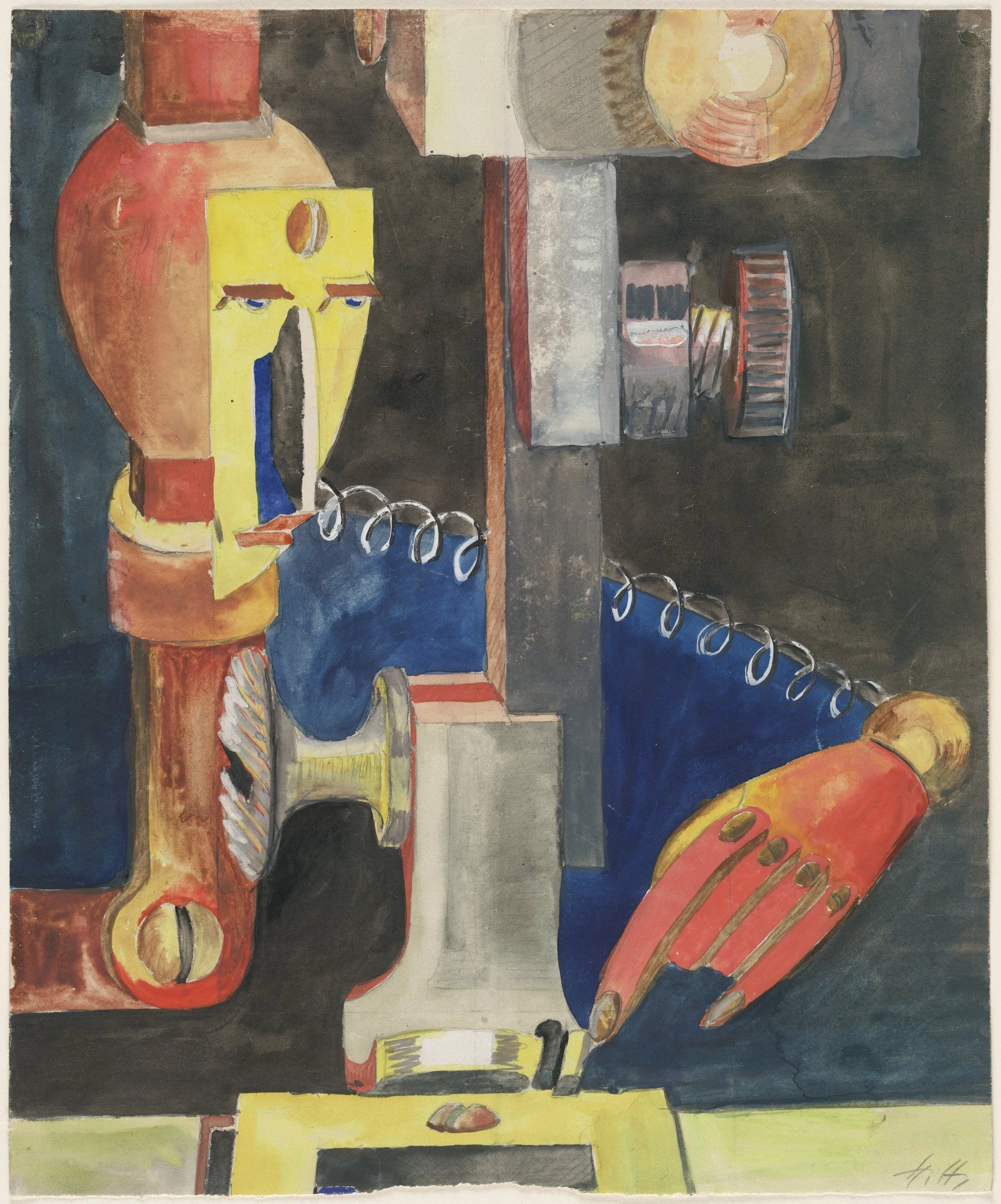

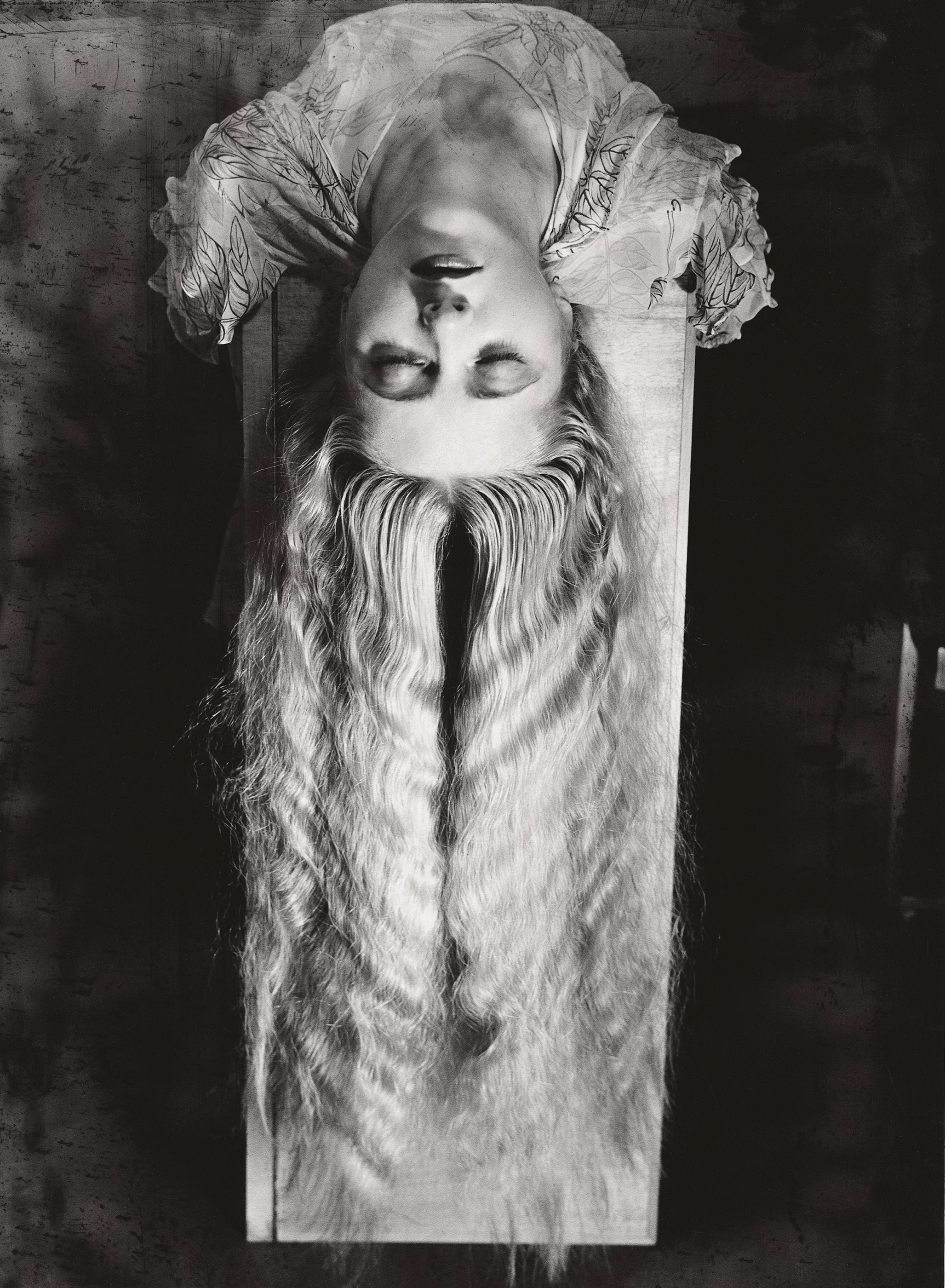

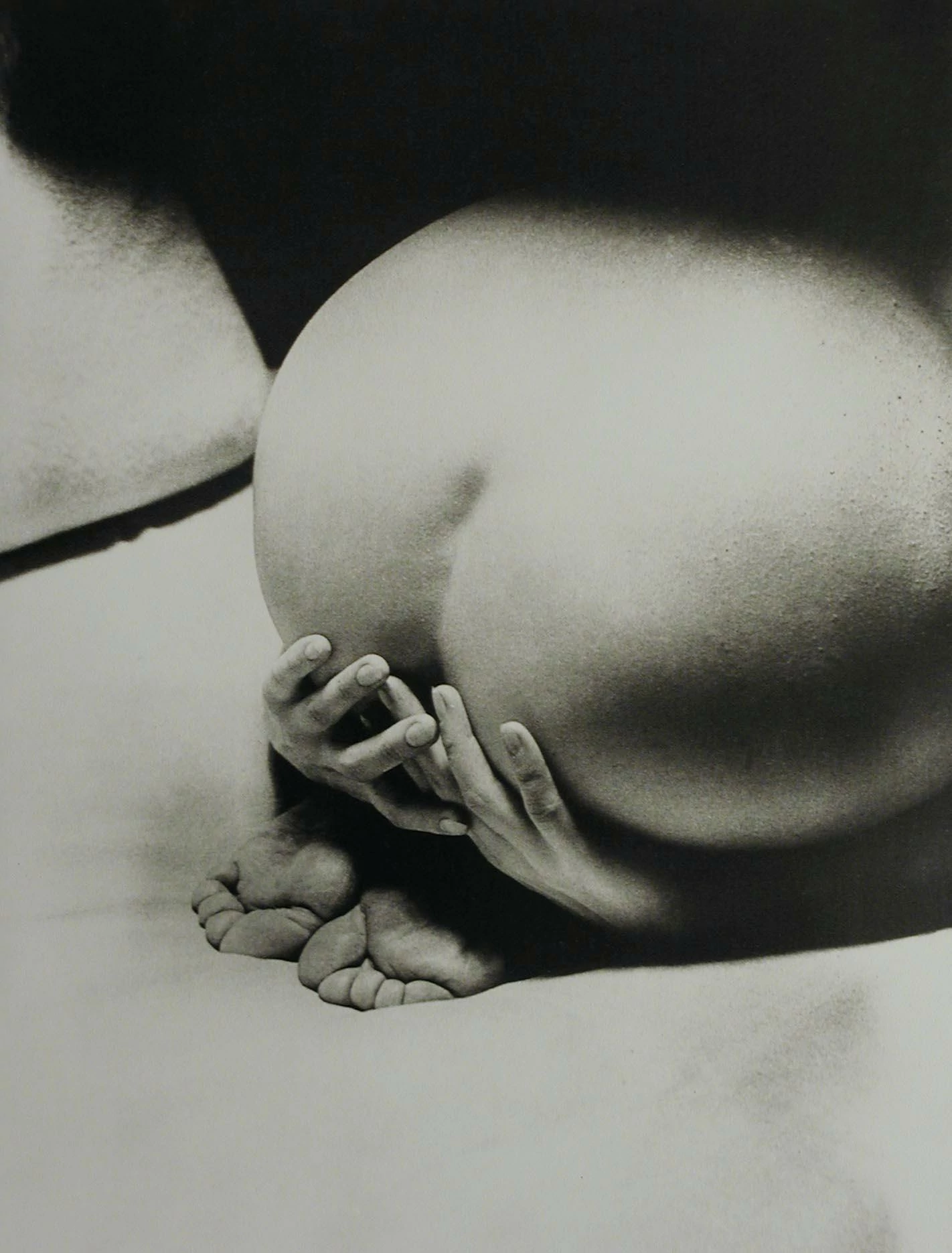

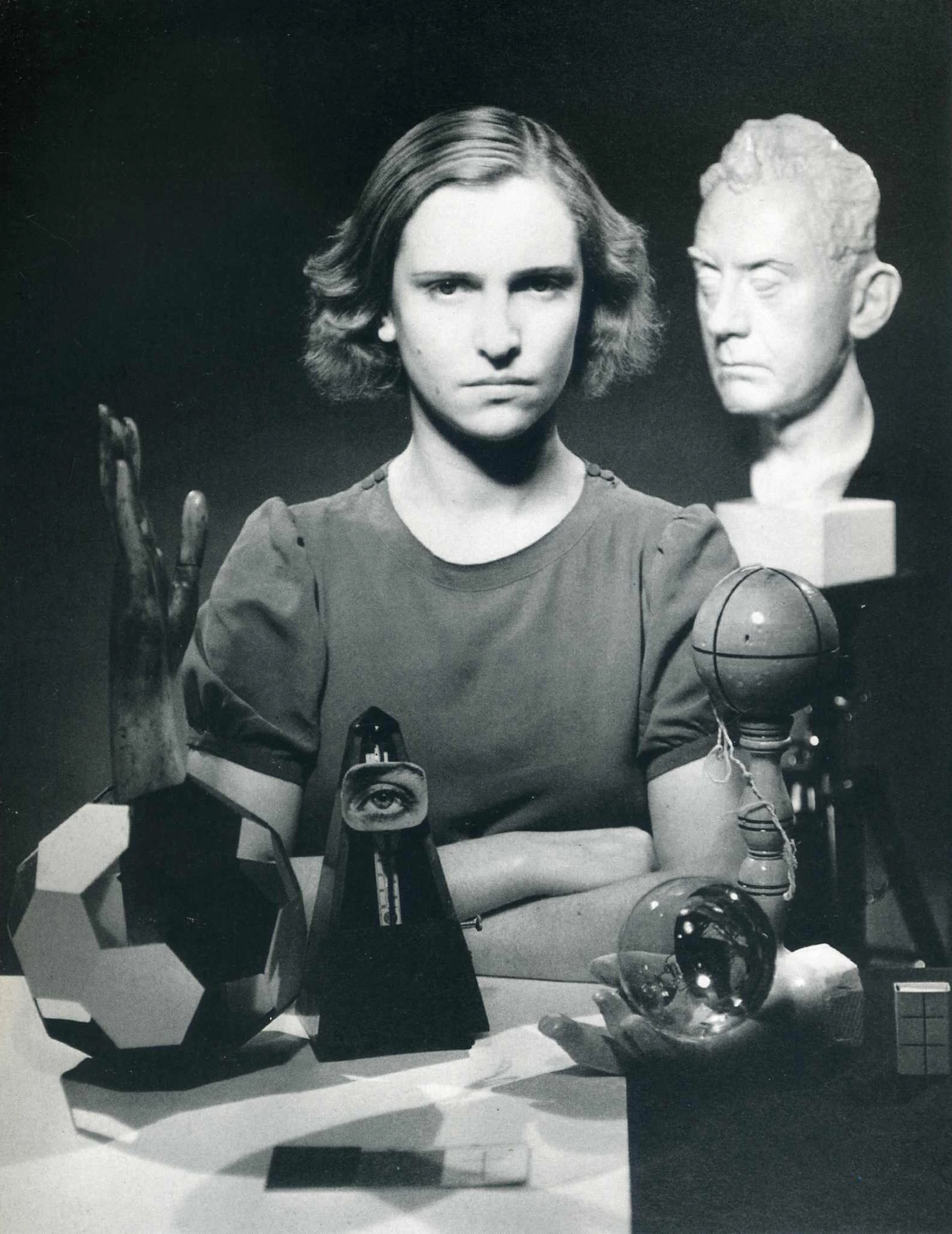

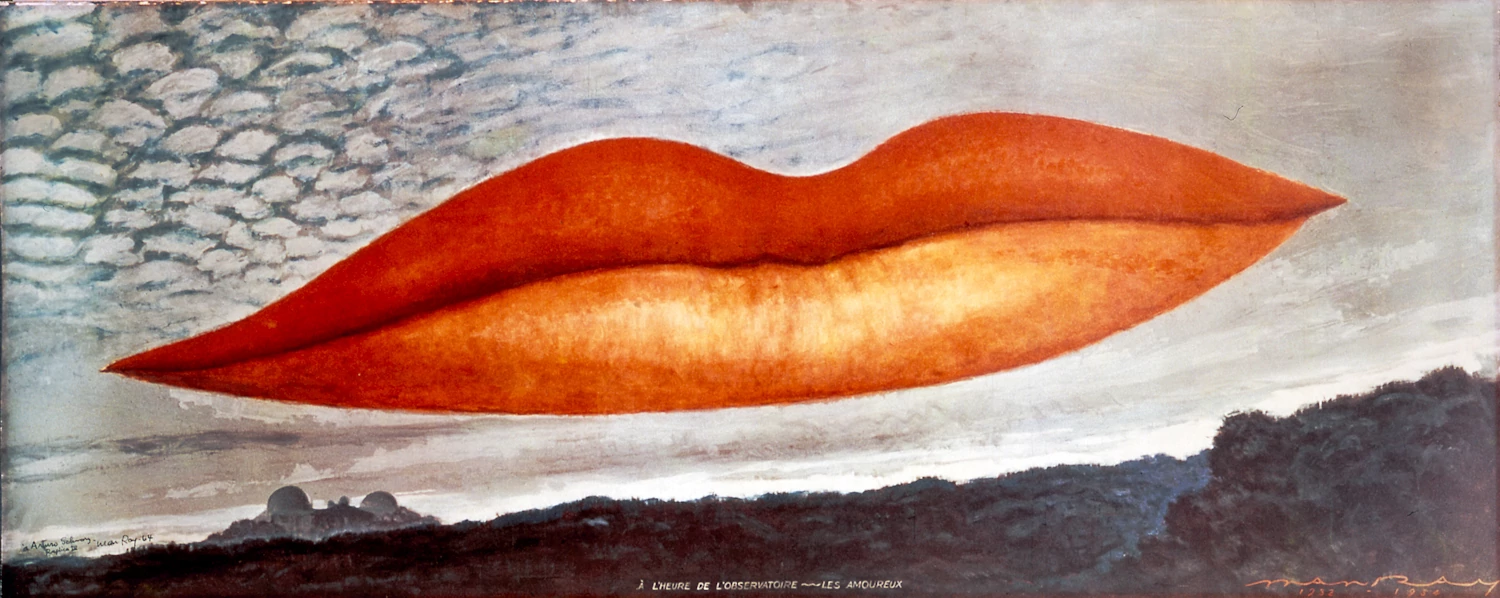

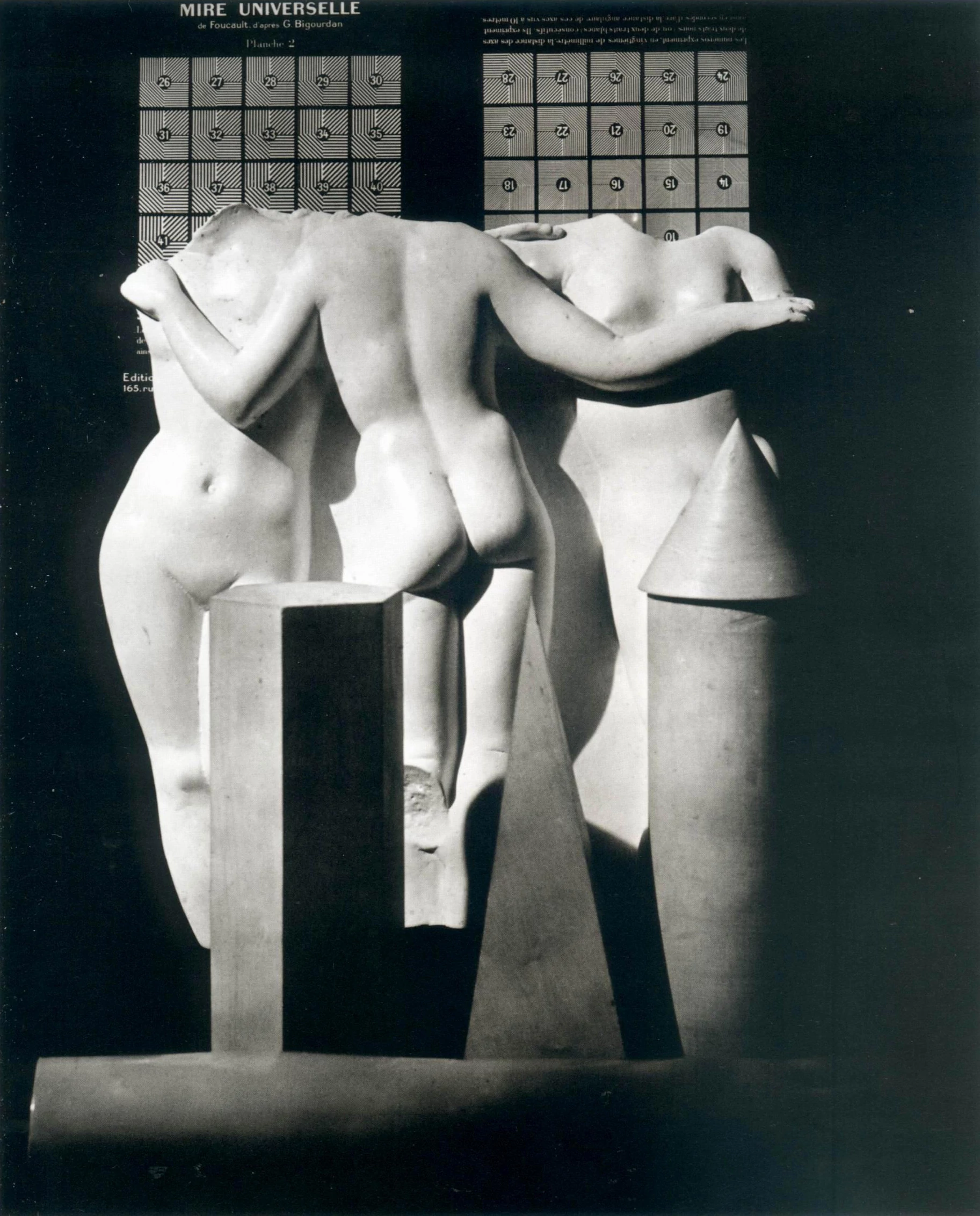

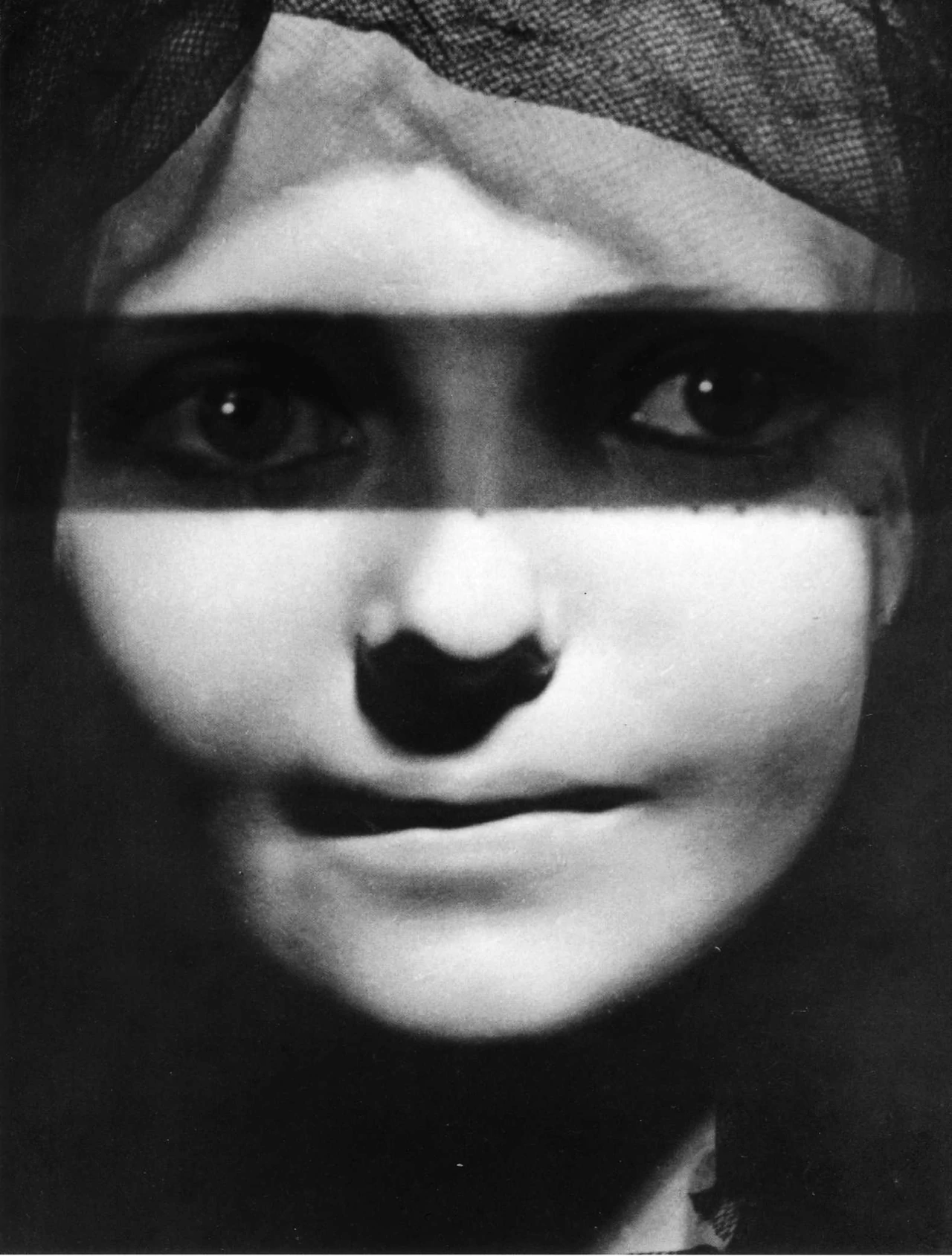

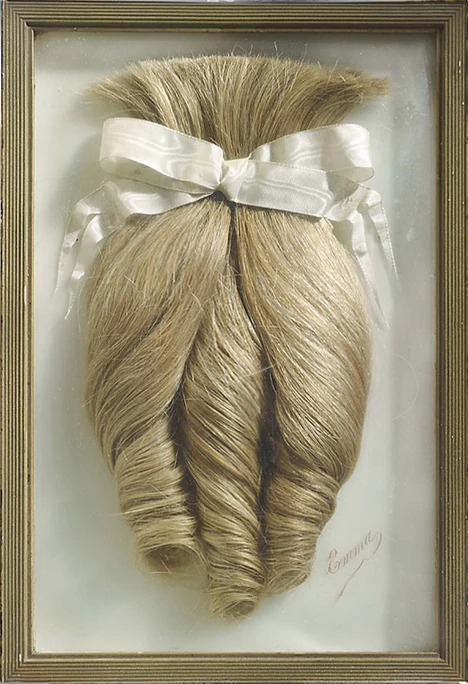

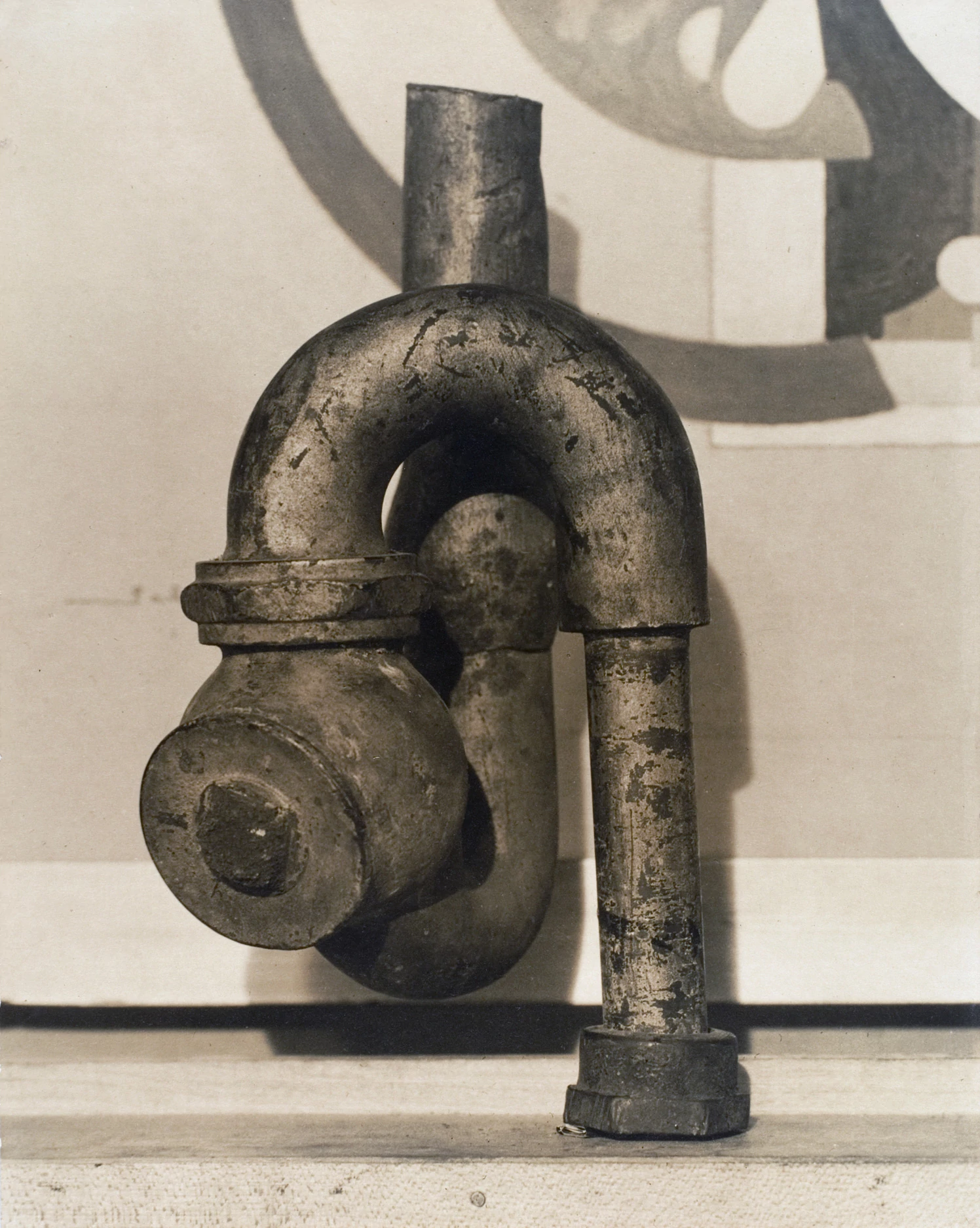

New York became another hotbed for Dadaist chaos, through the collaborations of French artists Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, German Poet and performance artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and the American photographer and painter Man Ray. With its geographic distance from the horrors of WWI, New York Dada was more light-hearted and absurd than its European counterpart. Duchamp dressed in drag, Freytag-Loringhoven submitted urinals to art shows, and Man Ray glued thumb tacks to everything.

In the wake of WWI, as the world slowly began to recover some sense of hope, Dada began to evolve. After ripping down centuries of expectations around the value and production of art, many Dadaists began to explore new styles and ideas, spawning Surrealism, Fluxus, and much of contemporary performance art. Dada had accomplished its goal, creating a clean slate from which to begin again.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Dada? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

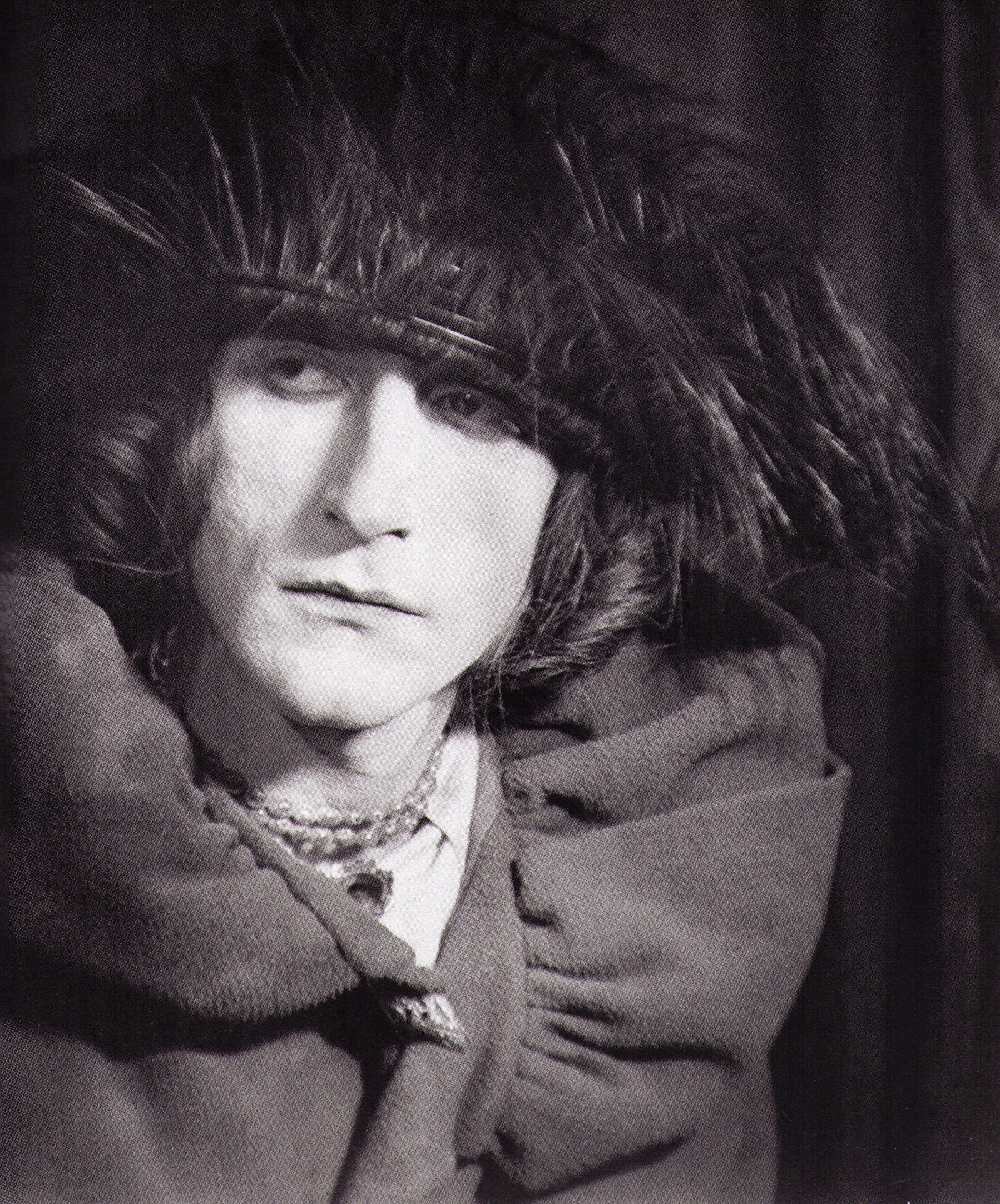

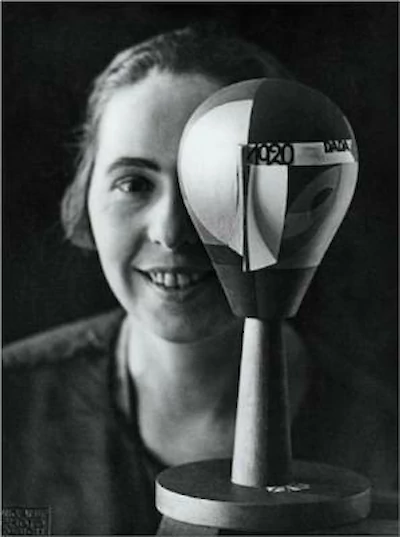

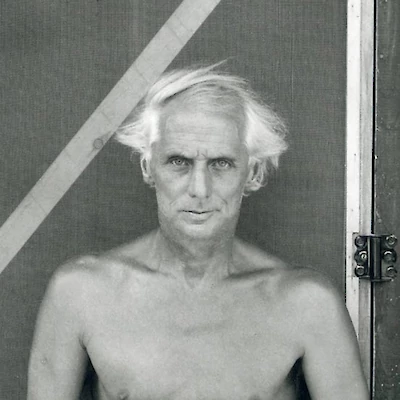

A living collage

1874 – 1927

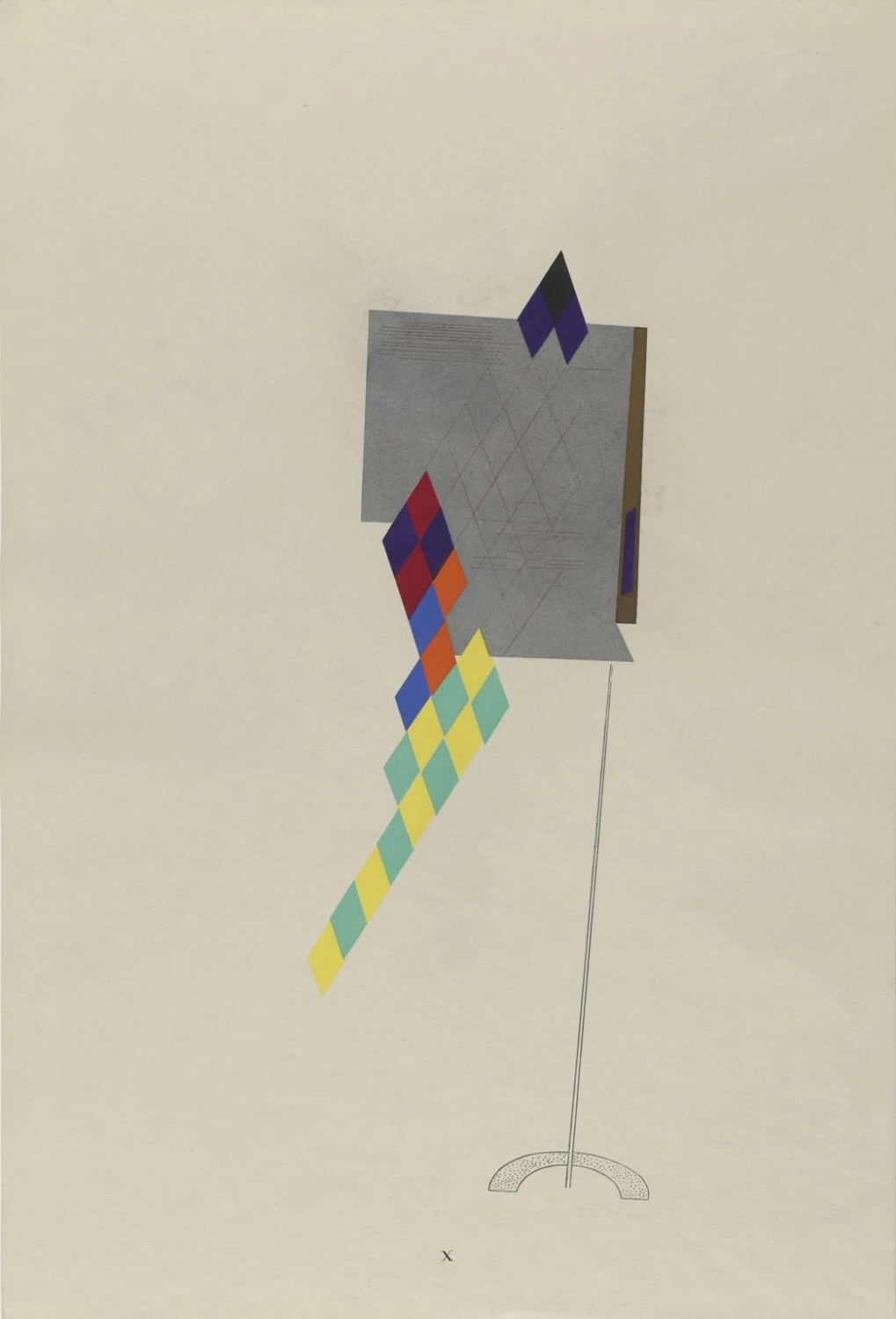

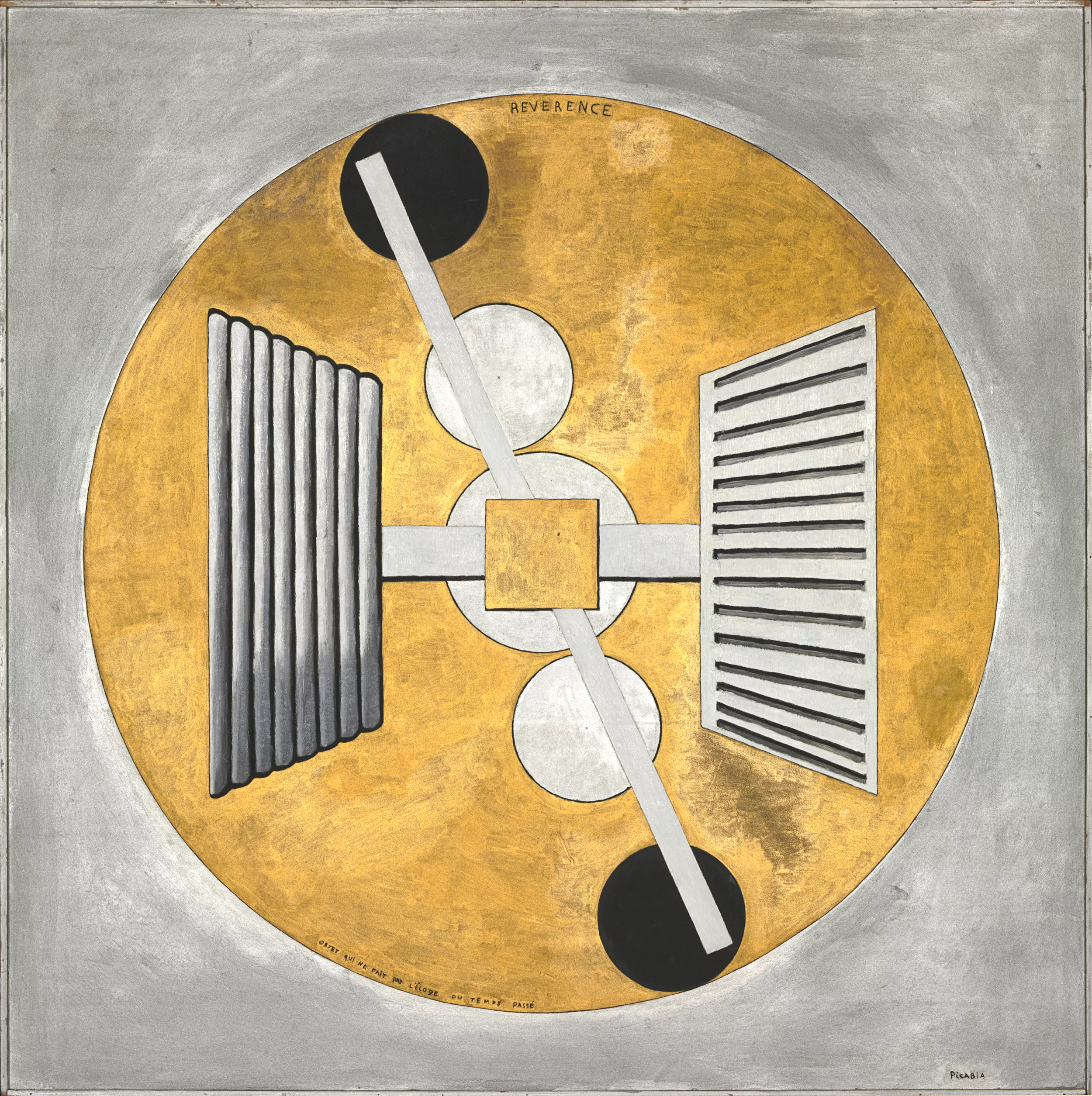

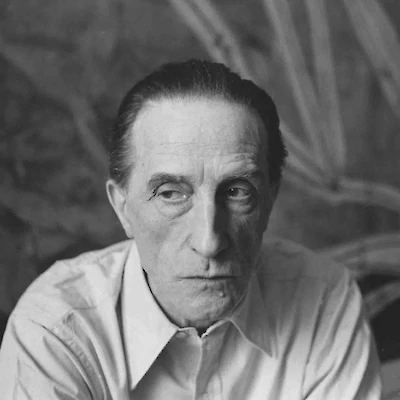

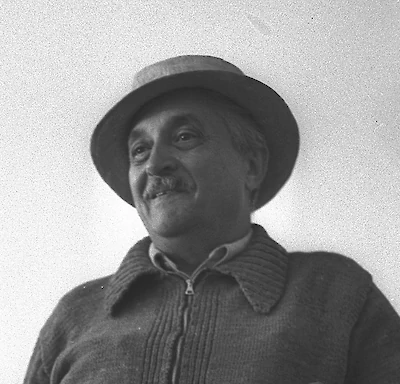

Giving art a cheerful middle finger

1887 – 1968

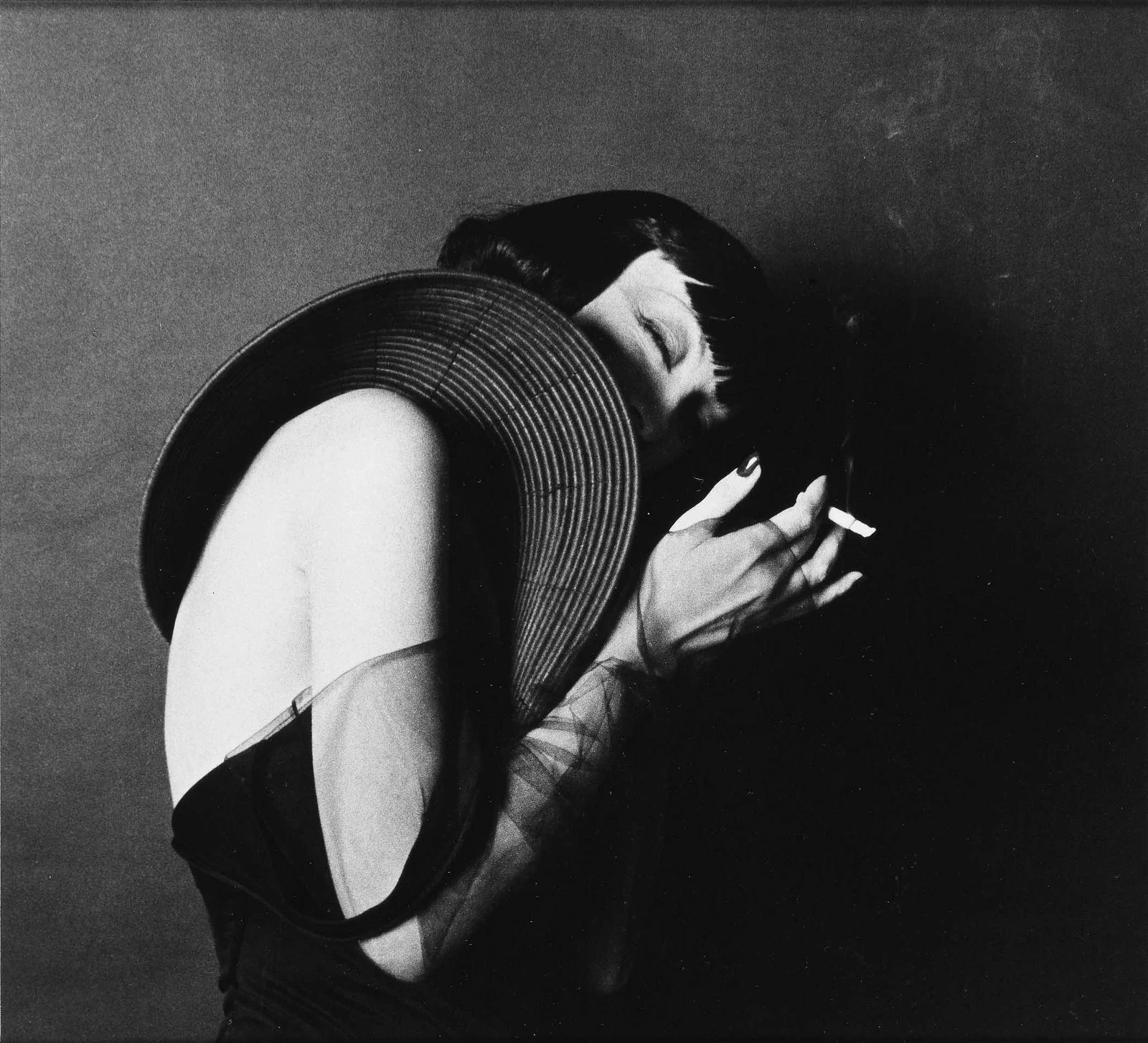

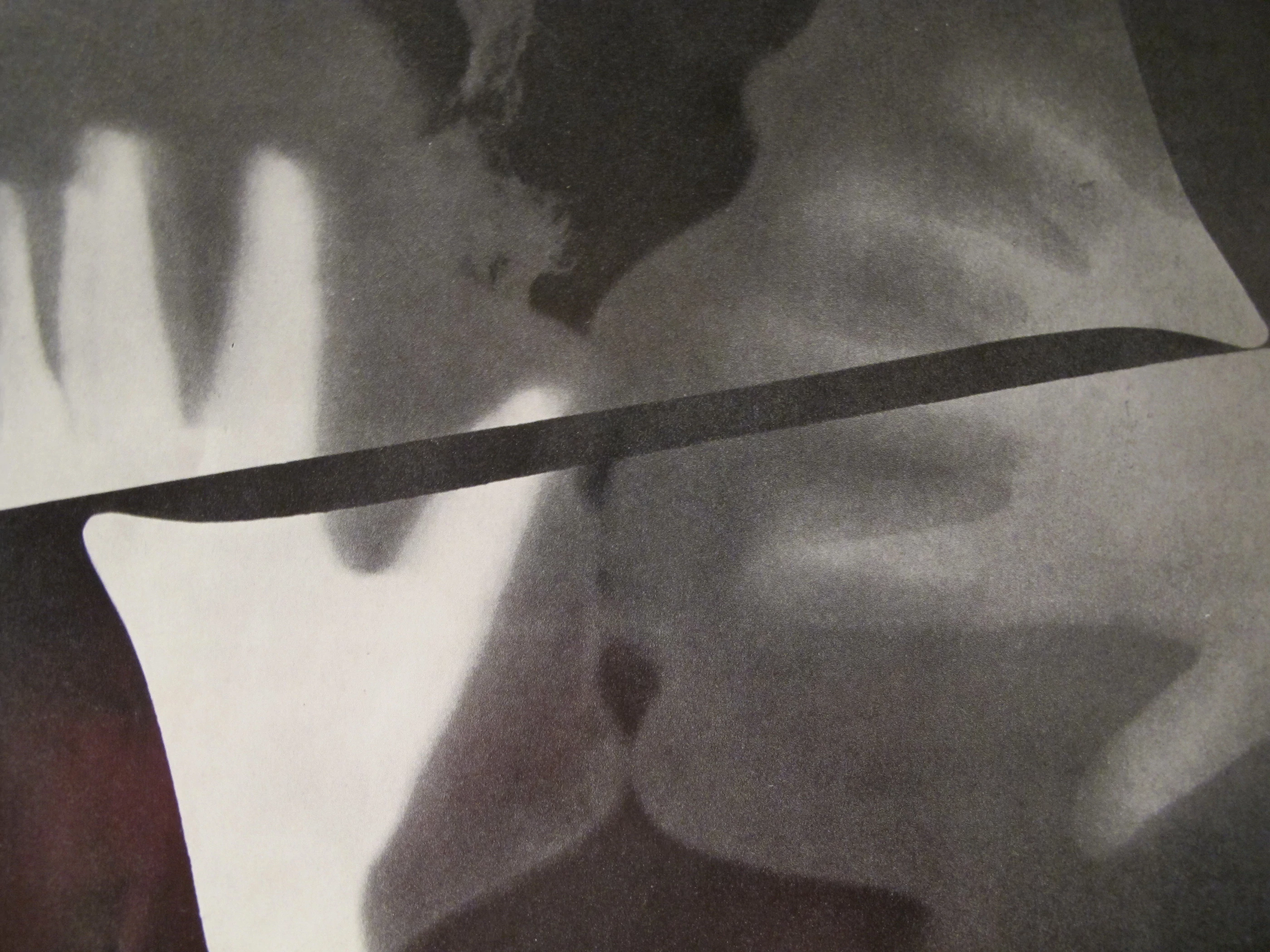

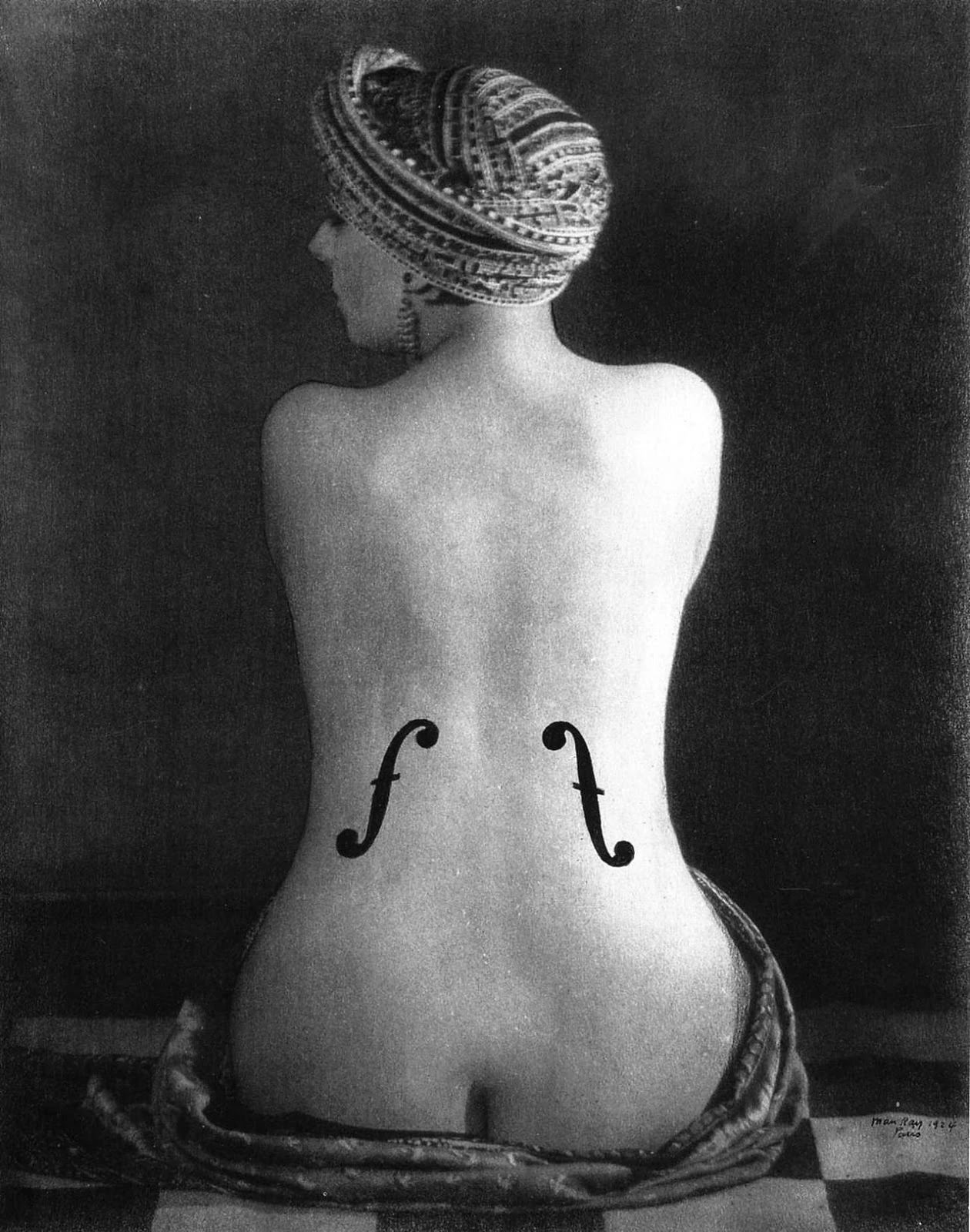

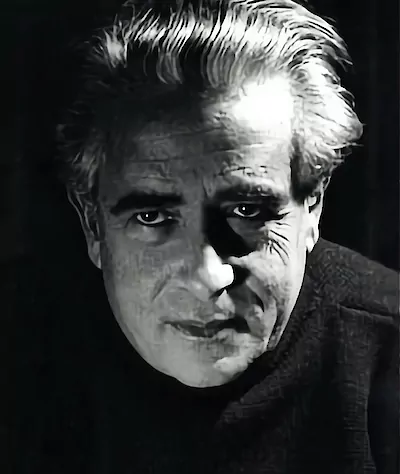

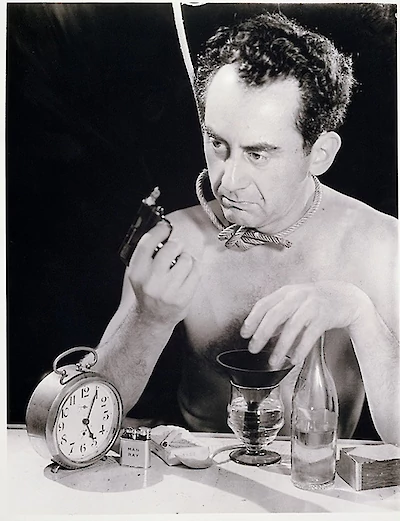

Humor, sex, and a new camera

1890 – 1976

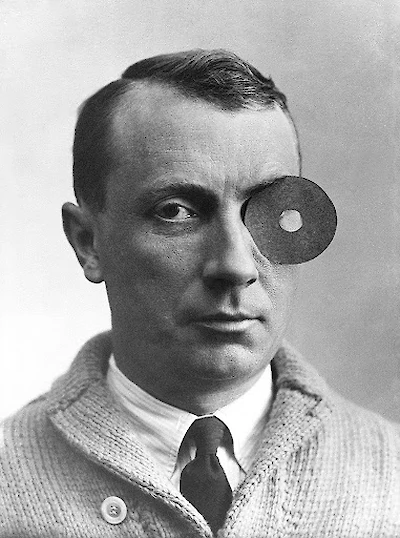

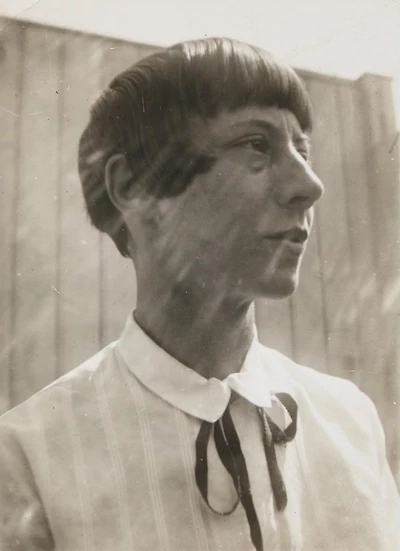

Trauma and displacement birth surrealism

1891 – 1976

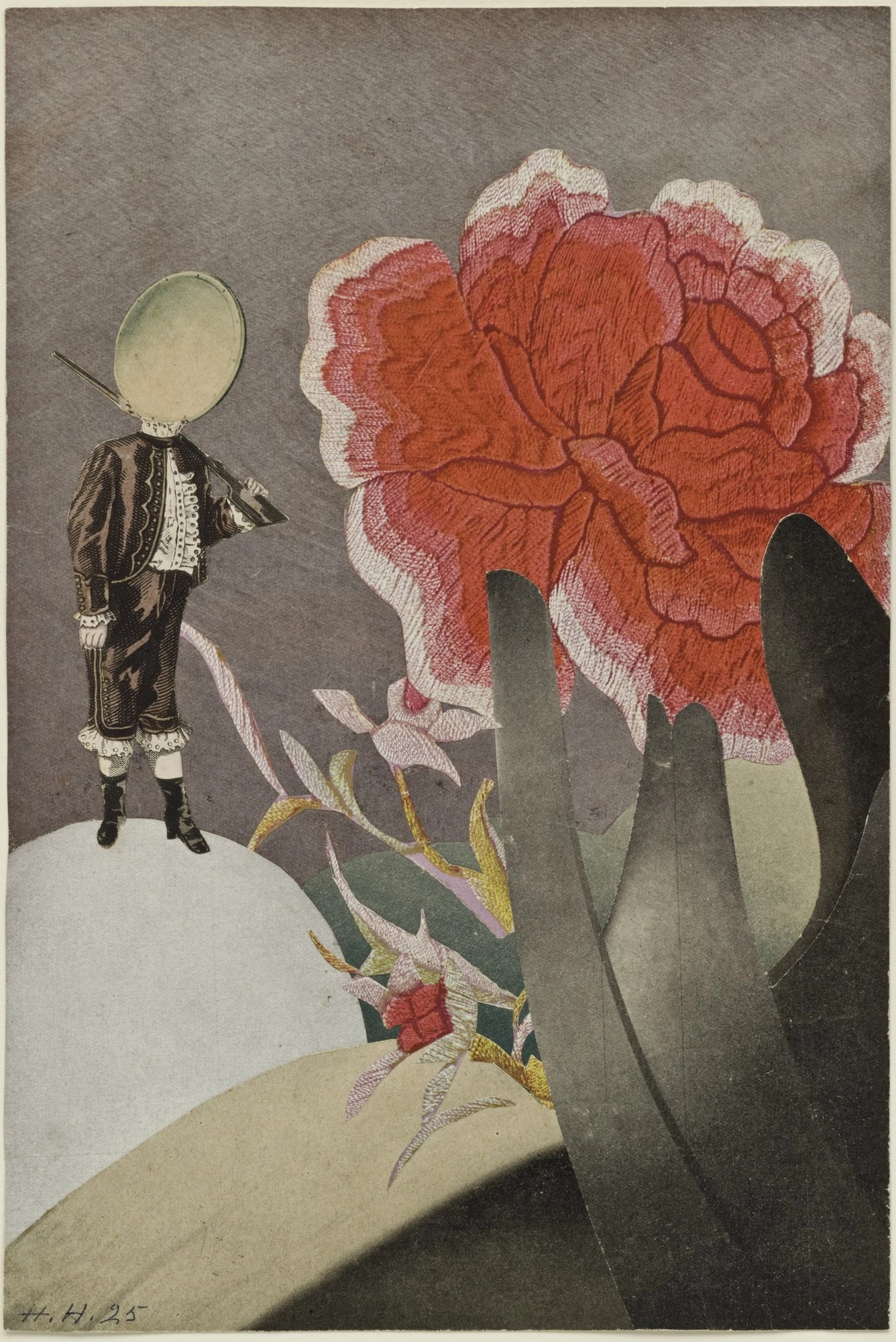

Dissecting the 'new woman' through collage

1889 – 1978

Just a word, and the word a movement.

We are like a raging wind that rips up the clothes of clouds and prayers, we are preparing the great spectacle of disaster, conflagration and decomposition.