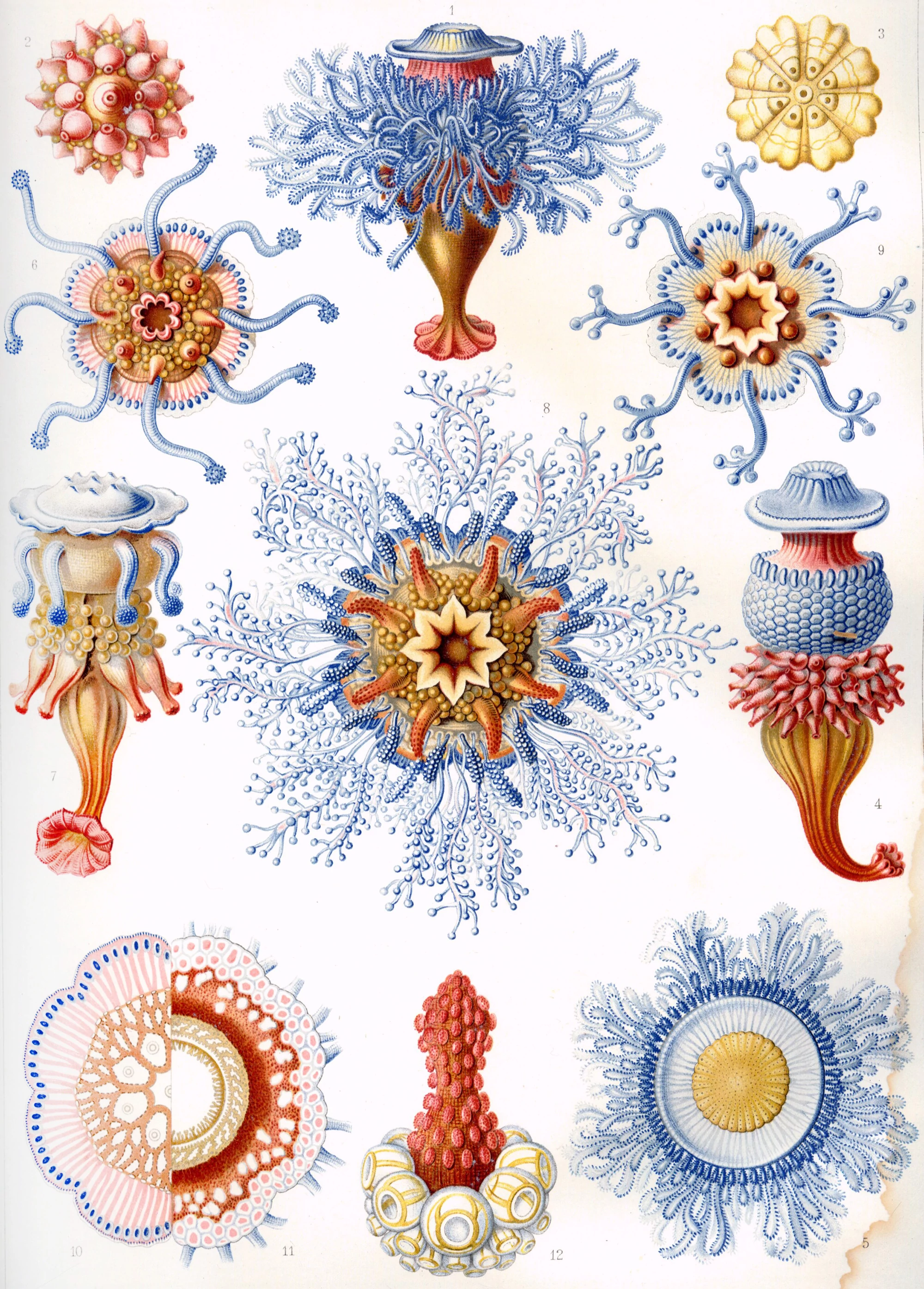

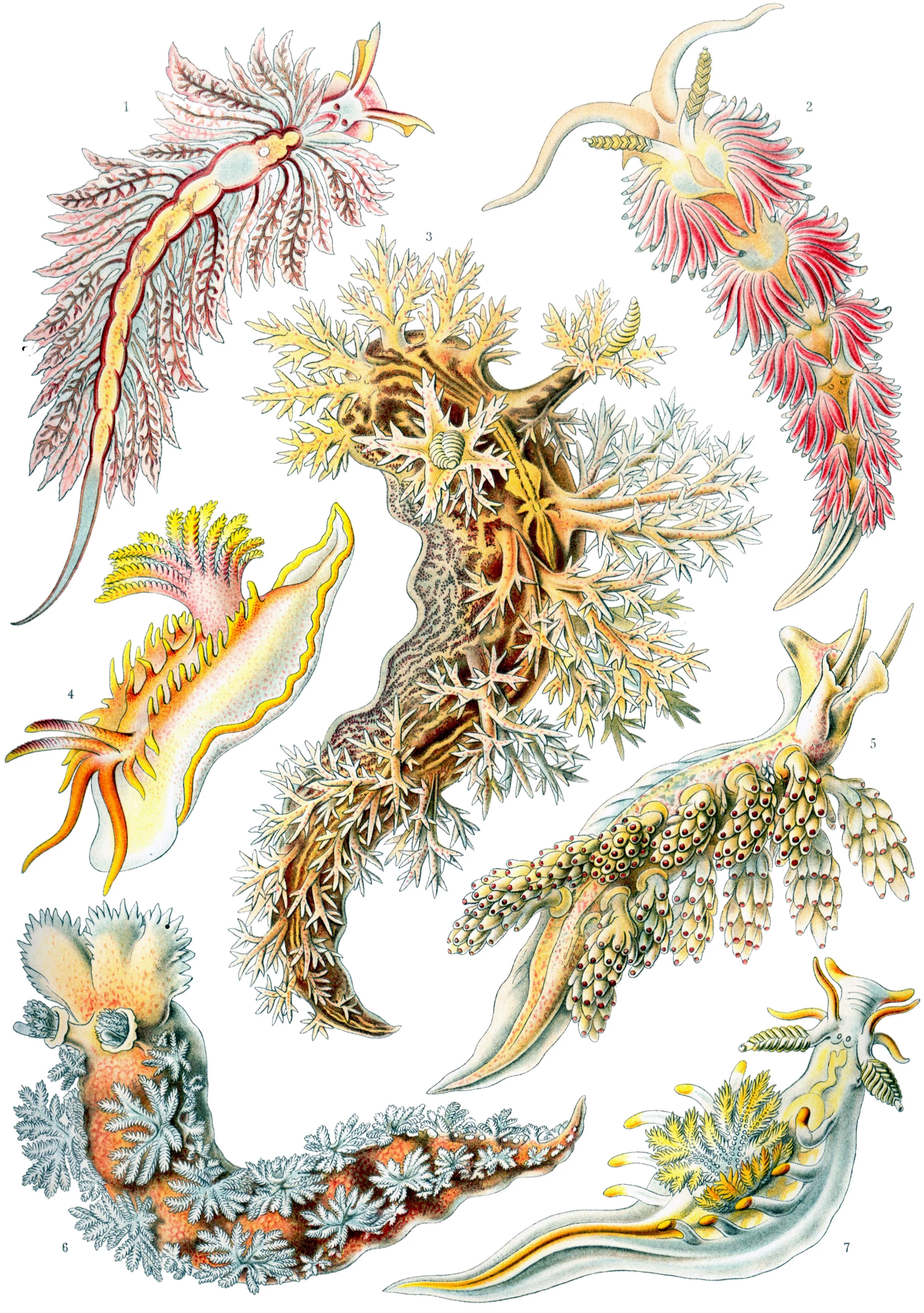

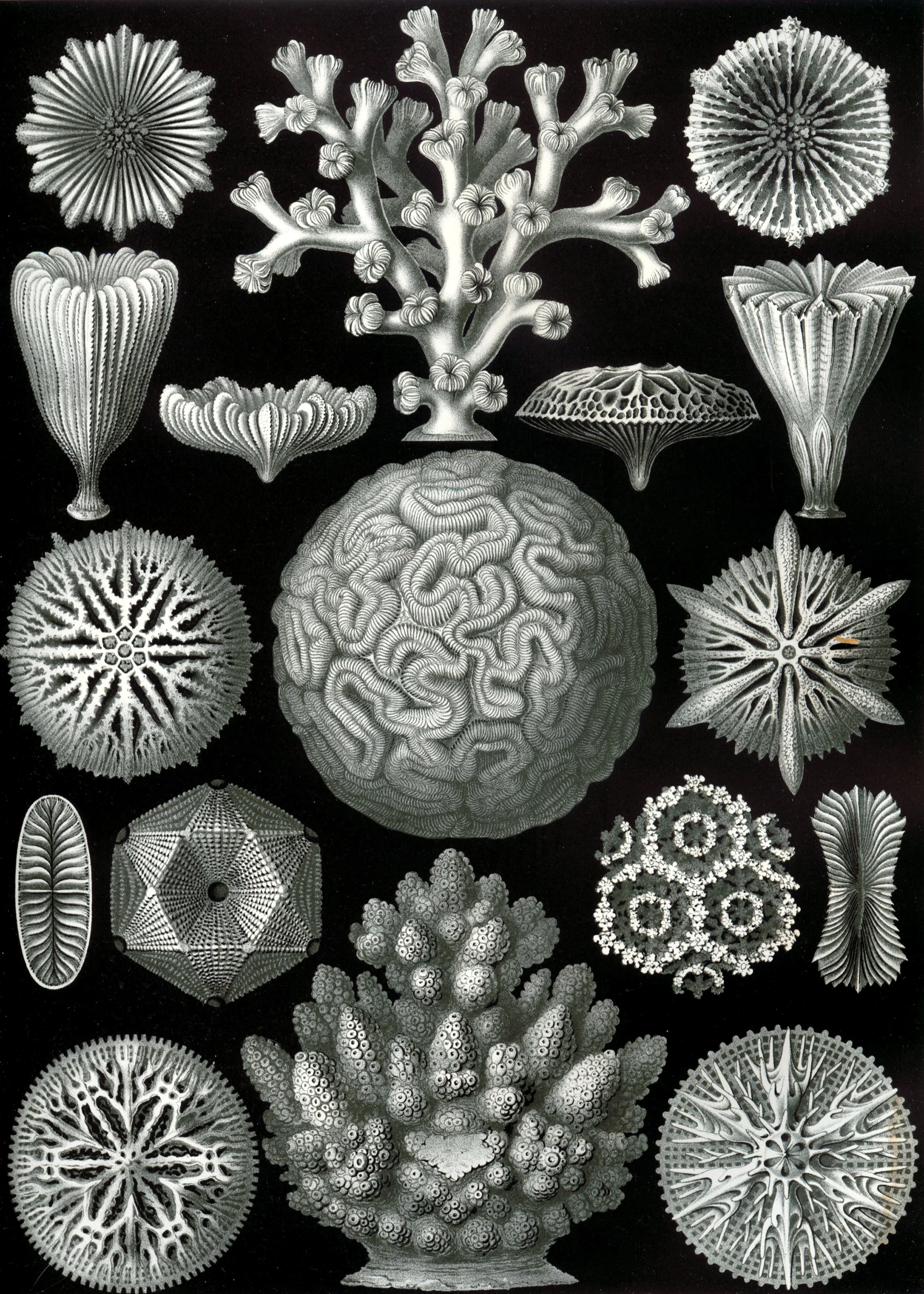

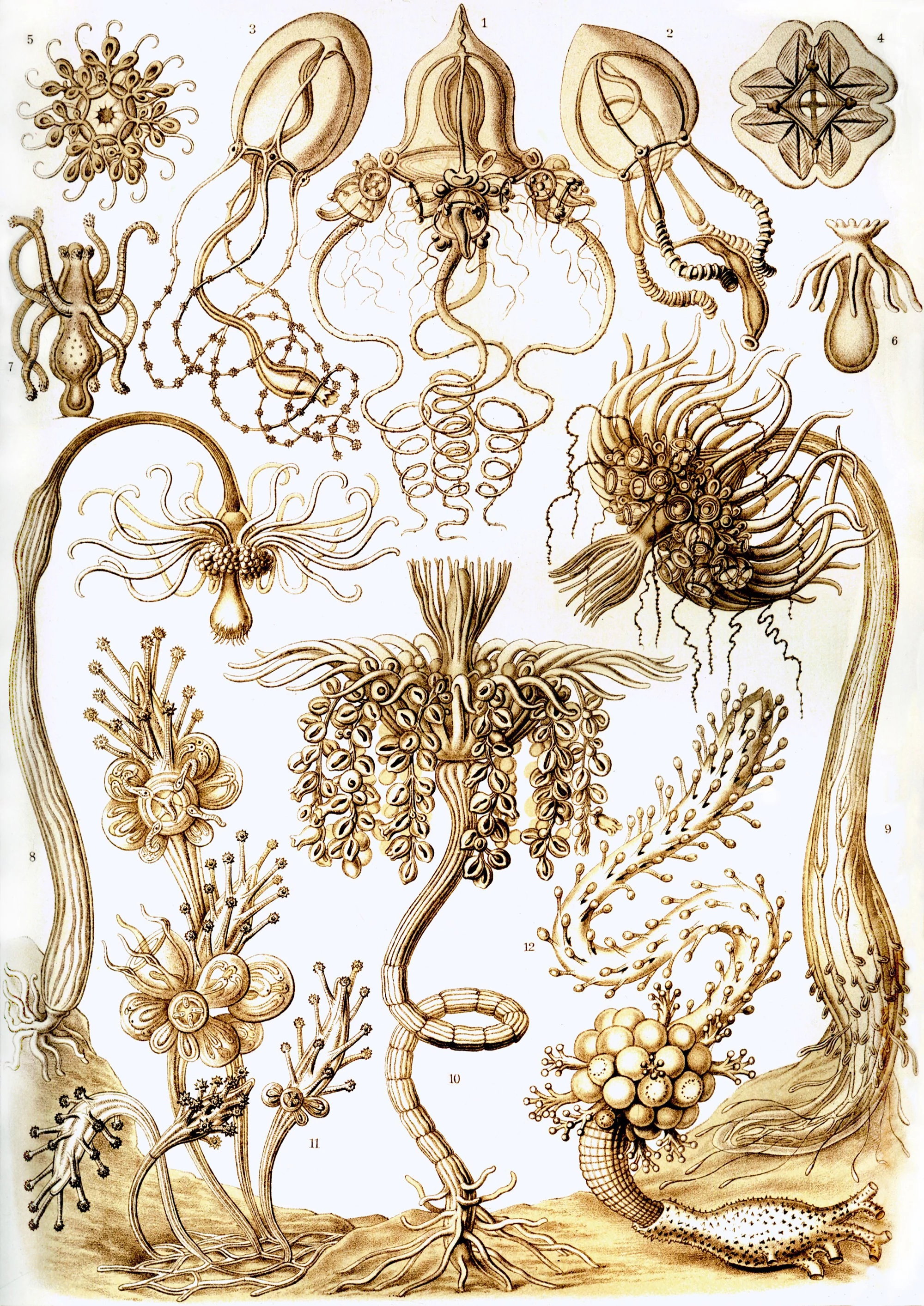

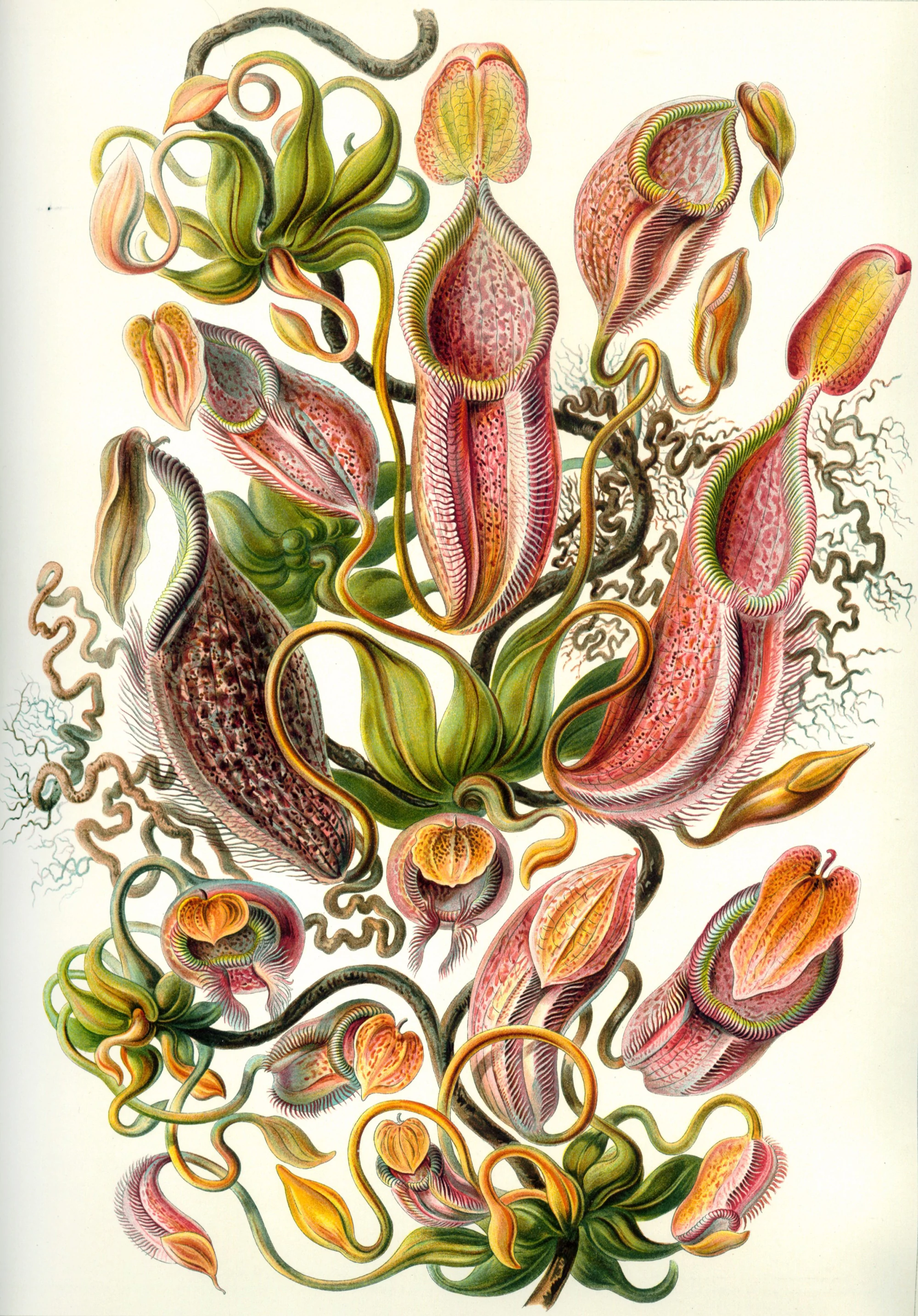

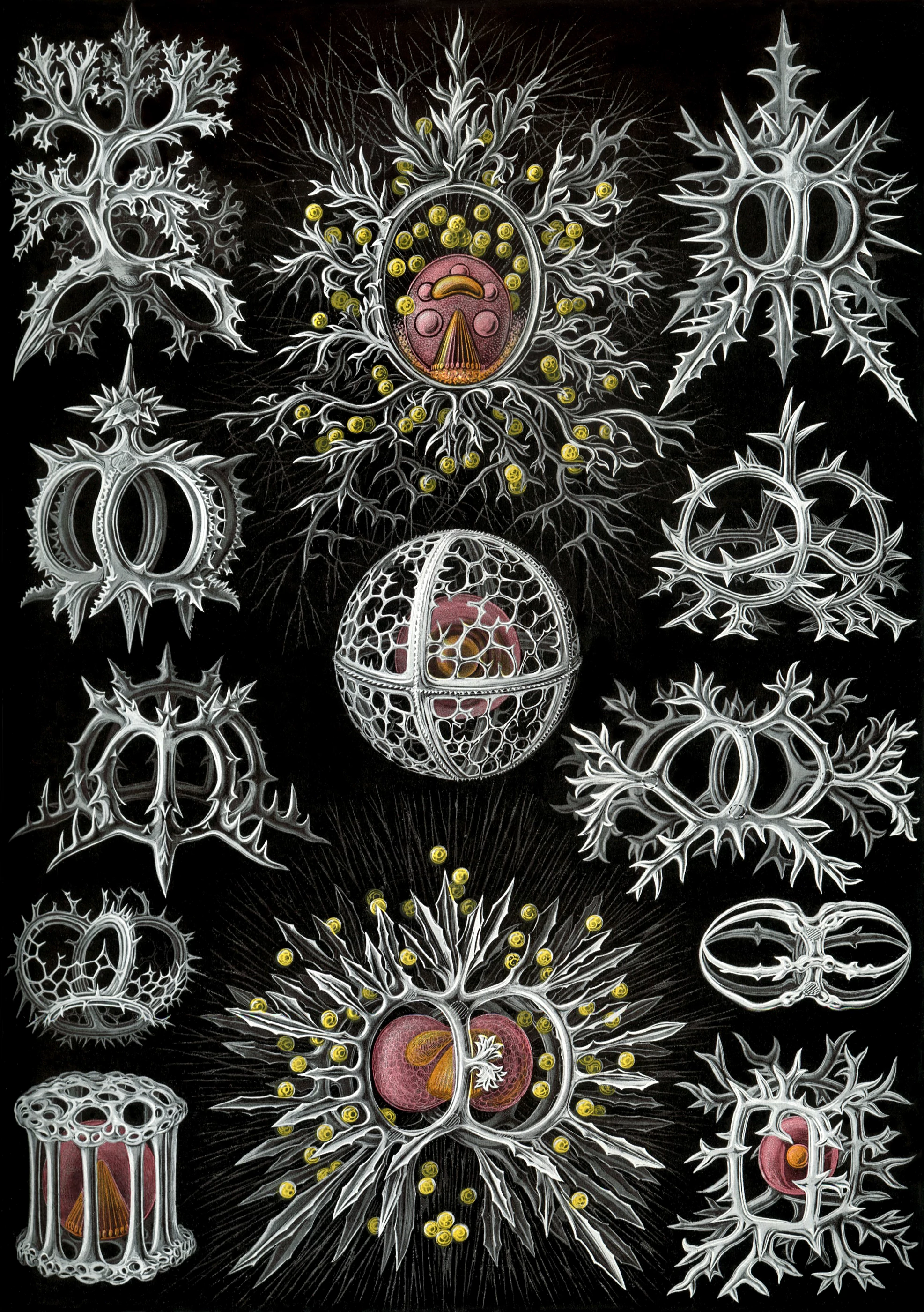

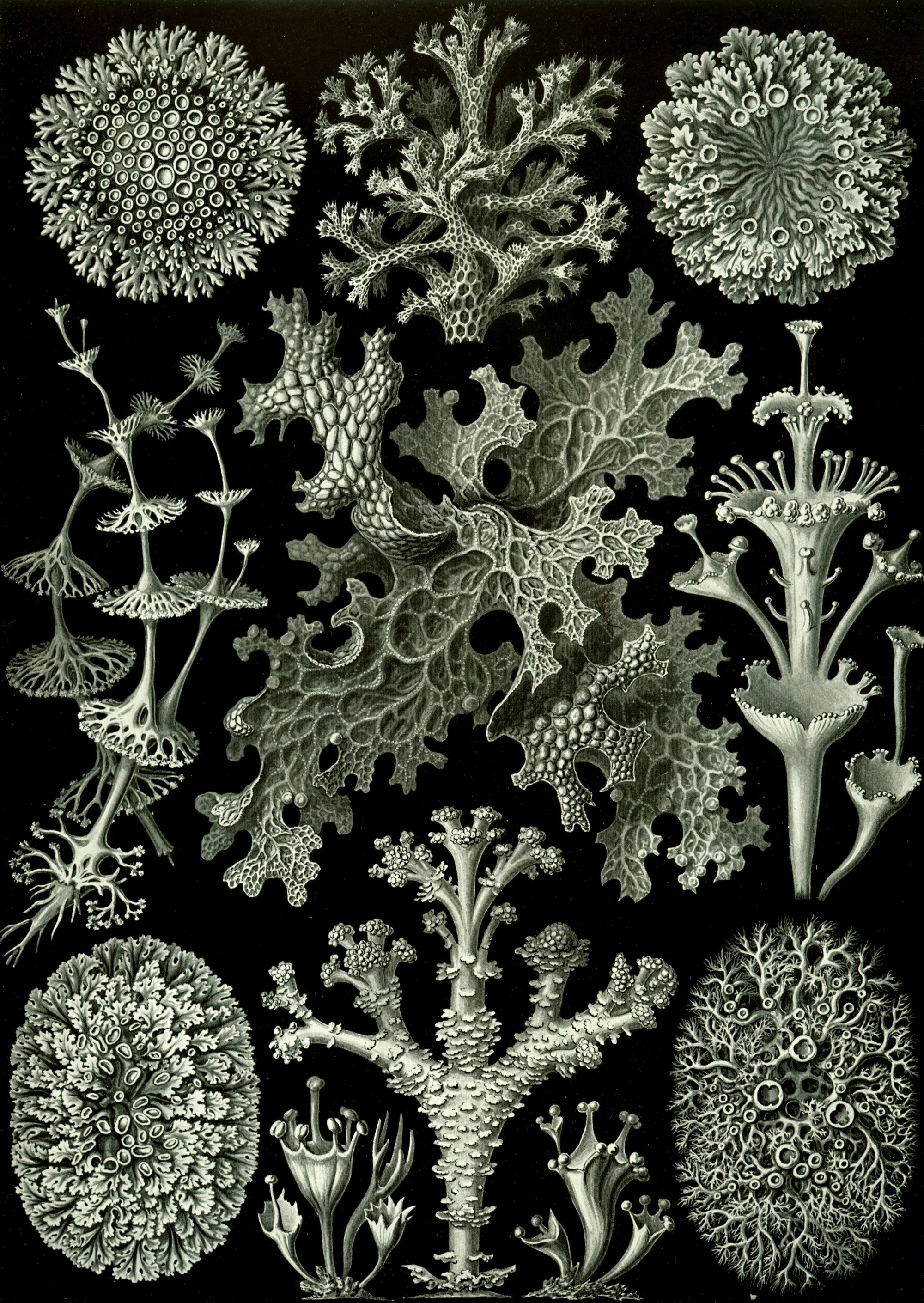

In 1864 Ernst Haeckel turned thirty and read, for the first time, Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Haeckel was a newly minted biologist, having earned a doctorate in zoology two years before. Haeckel had settled into a professorship of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, where he studied underappreciated forms of sea life—annelids, or segmented worms, radiolaria protozoa, and the ever-useful porifera, or sponges.

The Origin of Species was gasoline to Haeckel’s intellectual fire. While Darwin’s theories were cautious and technical, Haeckel was inspired to make more dramatic claims. Haeckel considered natural selection merely a starting point, incorporating Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s theory of ‘soft inheritance’ and his own observations of the morphology of sea sponges and protozoa. He published his grand unified theory under the title Generelle Morphologie, in 1866. But Haeckel’s Morphologie was a flop. The writing was dry, the books sold poorly, and even Darwin himself was unable to complete it.

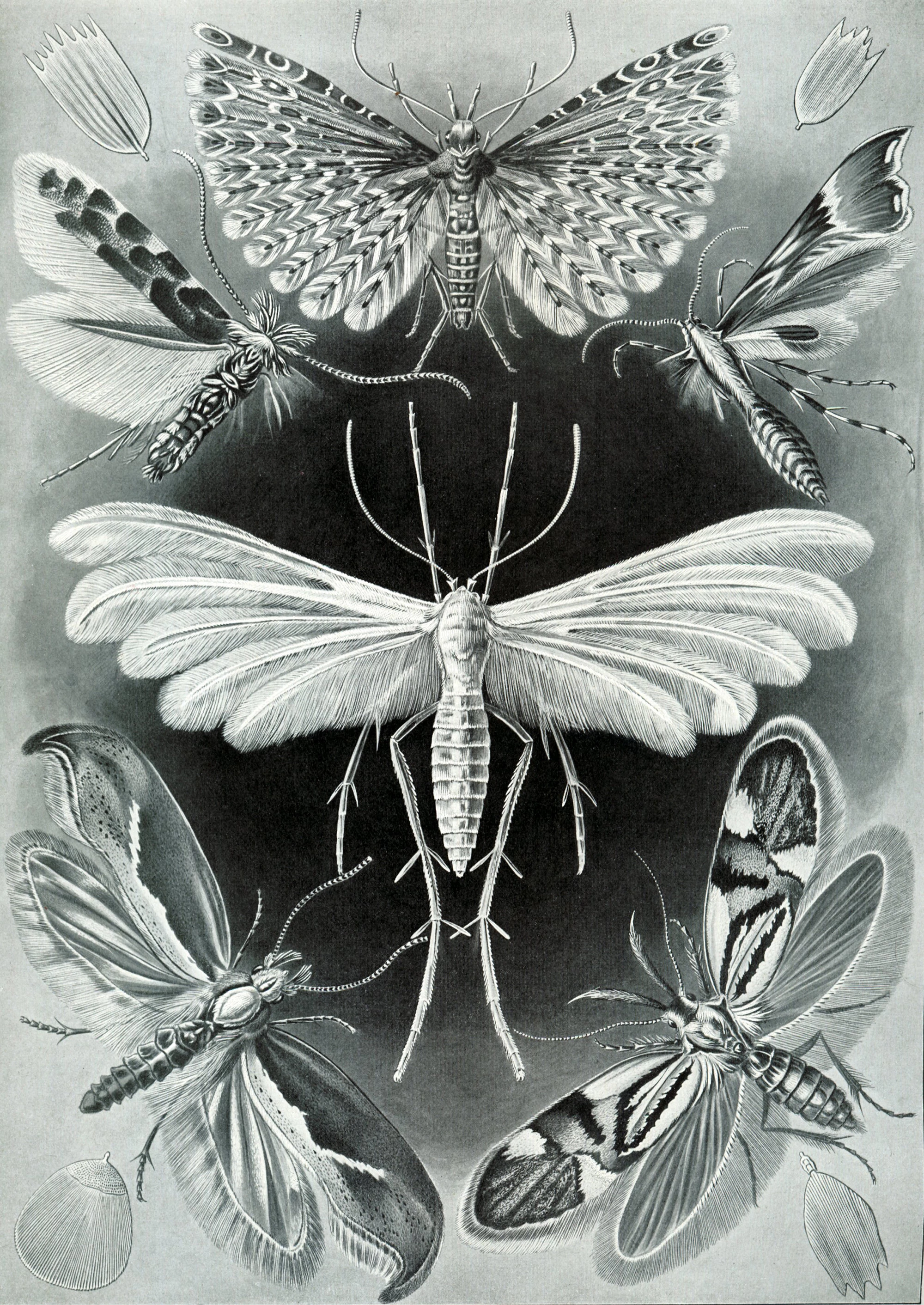

But while his writing was stiff, Haeckel’s public speaking was dynamic. In a series of well-attended lectures open to both students and local townspeople, Haeckel laid out his comprehensive theory of evolution in more conversational terms, and supported the lectures with his drawings of embryos and specimens. These lectures were transcribed by his students, and collected into his second book, Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte, which catapulted Haeckel into the aggressive world of popular science.