Neolithic

Beautifying the functional and moving big rocks

The glaciers of the northern hemisphere were finally receding. New lands emerged from under the ice, and the seasons slowly became more predictable. Humans were quick to take advantage of this new stability, tracking the movement of celestial bodies to predict the warm weather that allowed grain to grow. With reliable food sources, following the herd migrations like their Mesolithic fore-bearers became less necessary, and hunter gatherer societies turned to agriculture and domesticating animals, settling down, and developing some of the earliest human civilizations. With increasingly domestic, community-oriented lives, crafts became specialized and refined, the functional objects of previous eras became opportunities for creative expression, and the development of religion and superstition led to ritual burials and massive stone monuments that mapped to the stars.

Though the artists and craftspeople of the Neolithic worked thousands of years before our time, many of their creations remain surprisingly relatable today—ceramic vessels that wouldn’t be out of place on a modern table, bone flutes that can still carry a melody, and painting traditions that are practiced to this day.

Ceramic vessels are one of the most pervasive neolithic art forms. Pottery was developed in the Paleolithic era, with the earliest known examples found in the Xianrendong cave in China dating from c.18,000 BCE and Japanese Jomon pottery dated to 14,500 BCE, but by the Neolithic era it had spread to sub-Saharan Africa, Persia, the Middle East, India and the Americas. The relative stability of neolithic society enabled pottery to evolve from functional craft into truly spectacular works of art, like the swirling lines of the elegant vessels created by the Majiayao Culture that flourished from 3300-2000 BCE.

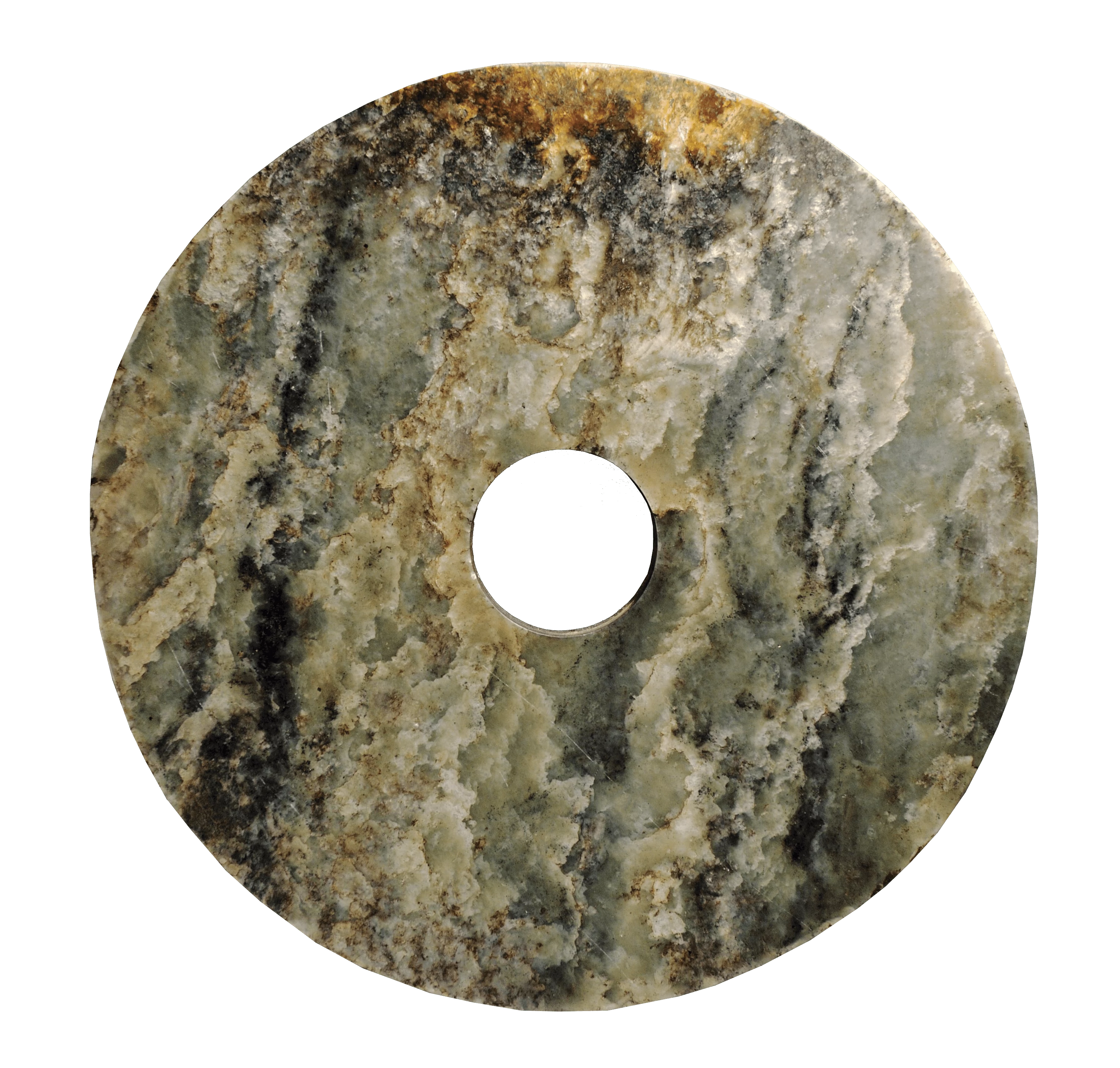

One art form that pervades nearly every society in history is the creation of little figures. Like pottery, human figures have been created since the Paleolithic era, but the Neolithic brought new sophistication. The terracotta Thinker of Cernavoda from Romania is from c.5,000 BCE but holds a pose of contemplation that feels immediate and relatable. The thinker has replaced the exaggerated thighs and breasts of the previous era’s ‘venuses’ with a naturalistic physique, and by c.3000 BCE an almost startling realism and detail can be found in the figurines from the Mesopotamian city of Uruk. A priest-king clenches his tiny fists below a detailed beard and inlaid eyes, bulls are lovingly sculpted down to the musculature. In China things were on a whole different level, with artisans from the Liangzhu culture carving jade, a notoriously difficult material, into the mysterious and beautiful cong tubes and circular bi disks.

Neolithic artists also continued the previous era’s traditions of painting and engraving on stone, with particularly arresting examples coming from Africa, Oceania and Australia. Some highlights: the unsettling ritual figures depicted in the Gwion Gwion rock paintings, previously called “Bradshaw paintings” from the Kimberley region of western Australia, the Niola Doa, maze-patterned monumental women engraved into a sandstone cliff on the Ennedi Plateau in Chad, and the largest animal petroglyphs in the world, the veritable zoo of 828 carvings of giraffes, ostriches, antelopes, lions, rhinoceros, and camels known as the Dabous Giraffes in north-central Niger. Rock art is awesome, get into it.

When we think of neolithic art, a very specific image springs to mind. Stonehenge. Creative pottery and the evolution of human depiction is all well and good, but the neolithic activity that absolutely dominates our curiosity is the herculean effort of moving giant stones into circles, and raising them to the heavens. There is a raw power to these monuments, from the seeming impossibility of their construction, the palpable sense of physical weight, and from their mysterious purpose. What did these ancient peoples value enough to expend this kind of energy? And while Stonehenge is impressive and deeply photogenic, the megalithic phenomenon is shockingly widespread. From the earliest known ceremonial structures at GöbekliTepe in Turkey, to the calendar circles of Nabta Playa in Egypt, to the stone labyrinths of the Caucasus Mountains in Russia, megalithic structures were created en-masse by neolithic cultures all over the world.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Neolithic? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.