Framed Artwork

Where did all the frames go?

Most of Obelisk’s images of artwork don't include the frame. The majority of my sources for artwork imagery: museum archives, Google Art Project, WikiCommons, etc, default to frameless images, I assume because professional photography of 2d artworks usually happens when a painting is being refurbished or documented, behind the scenes, removed from their display frames. Shooting this way is much easier, and lends itself to a better image. You can often tell when an artwork was photographed in a frame that was later cropped out by the dark shadow running around the edges of the image, not to mention that frames often hide a centimeter or so around the edge of the artwork.

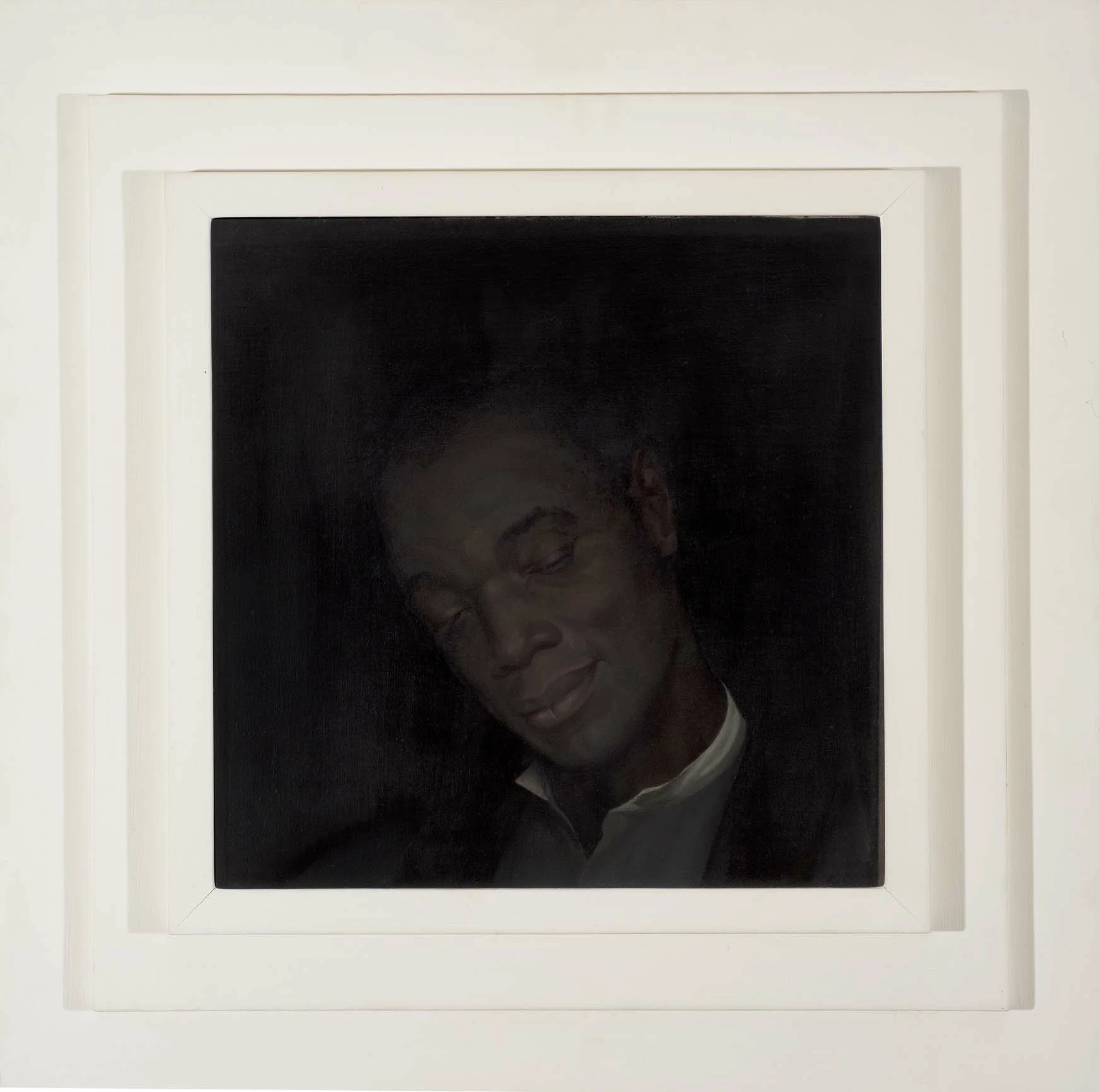

There’s more to the death of the frame than convenience. I suspect the frameless default reflects a contemporary bias towards the ‘pure’ presentation of art—that artwork is best seen in a white box, with no context and minimal framing, if any at all. Frames, specifically the giant gold ones that populate the premodern wings of every art museum ever, are ostentatious to the modern eye. Tacky. Gouche. A distraction from the photonic communication from the artist to the viewer, a tasteless wrapper of exclusivity and wealth.

I understand this bias, and feel it myself. I love looking at the smooth gradients of a Turner seascape or Velázquez’s trademark crimson in the disembodied void of a minimalist website. White background or charcoal gray, smooth, featureless, maybe a light drop shadow to lift images into dimensional space. No distractions. I've personally cropped out dozens of frames if not hundreds, cursing their intrusive shadows and delicately lightening image edges in a dubious attempt at digital restoration.

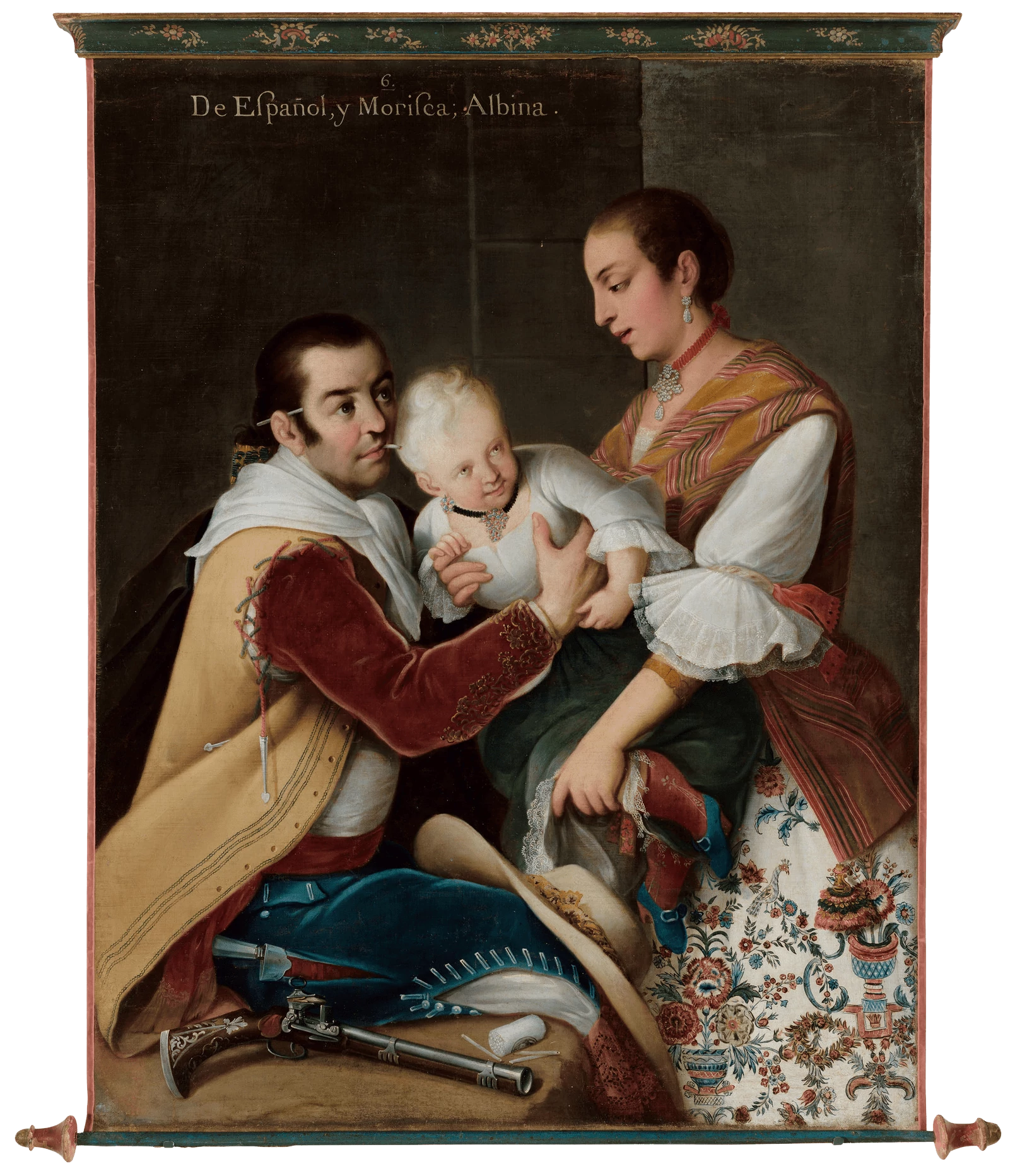

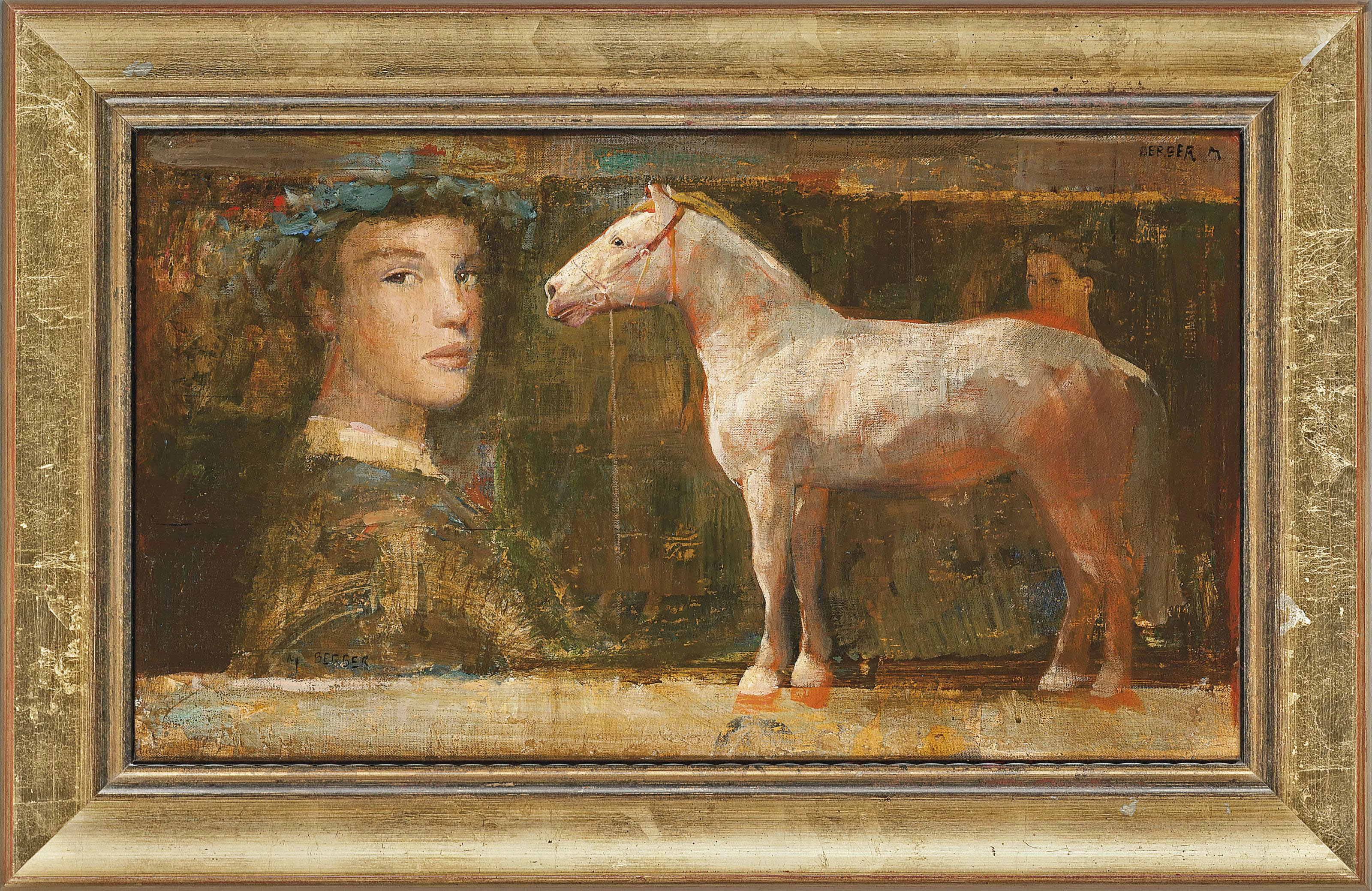

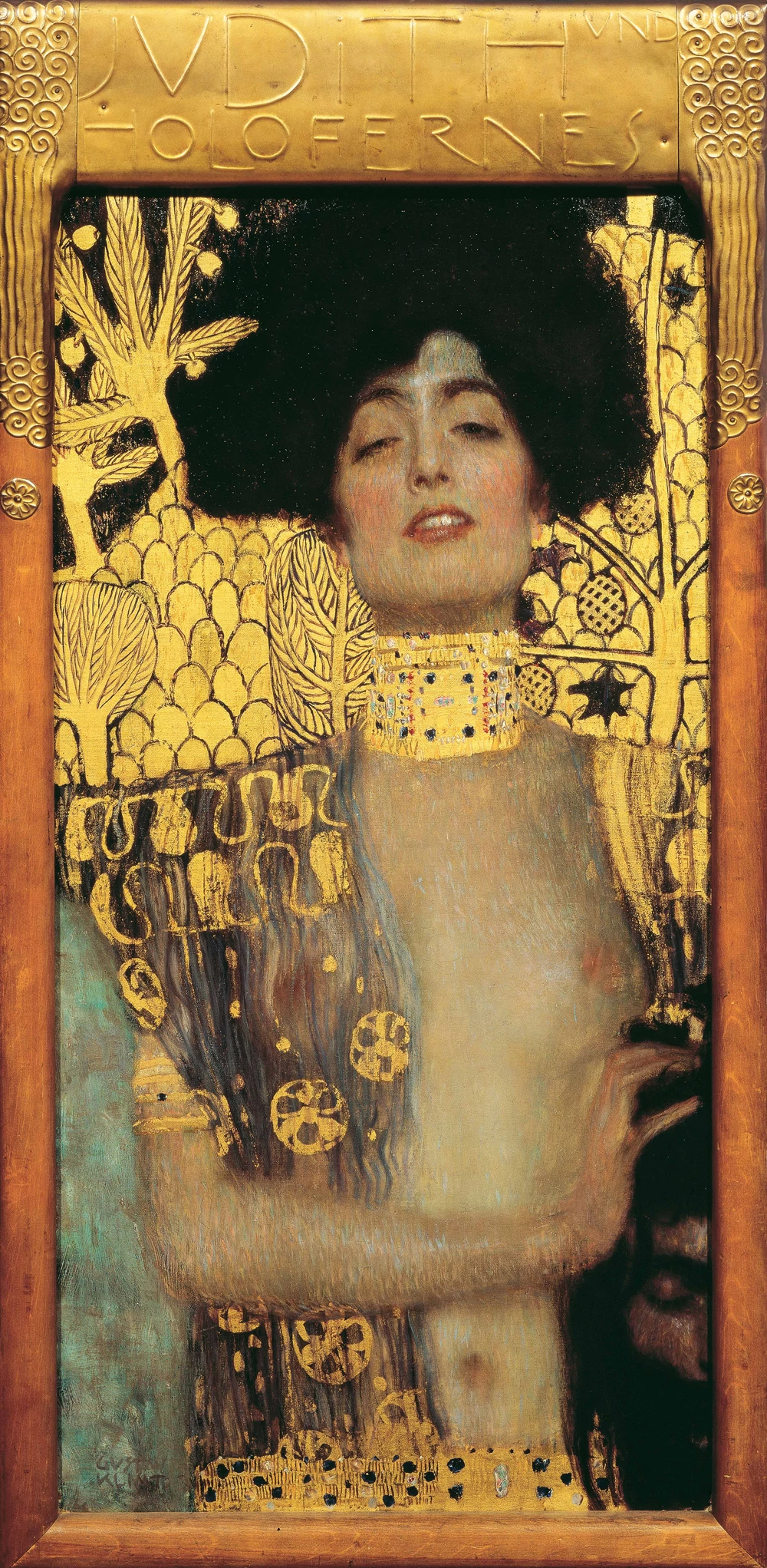

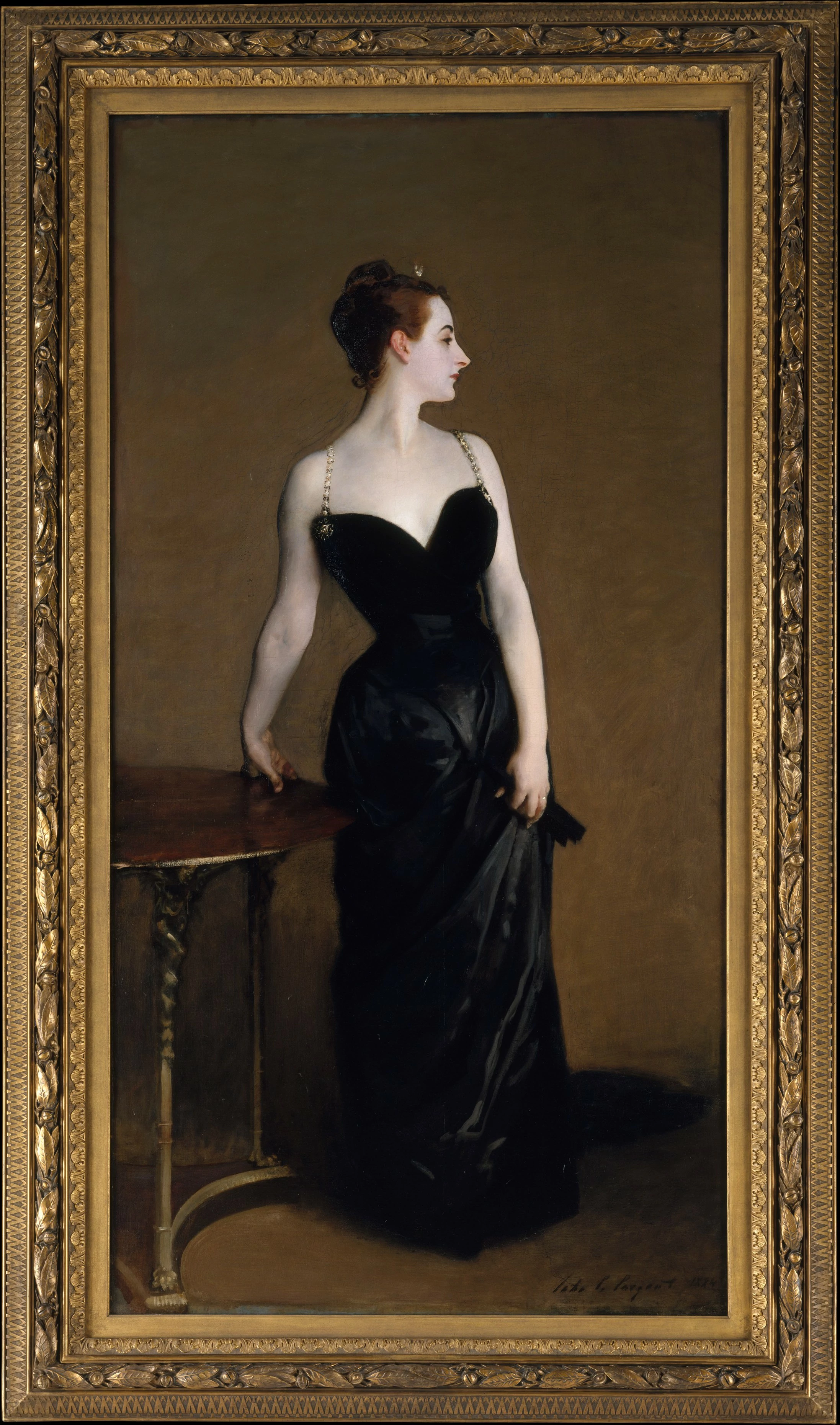

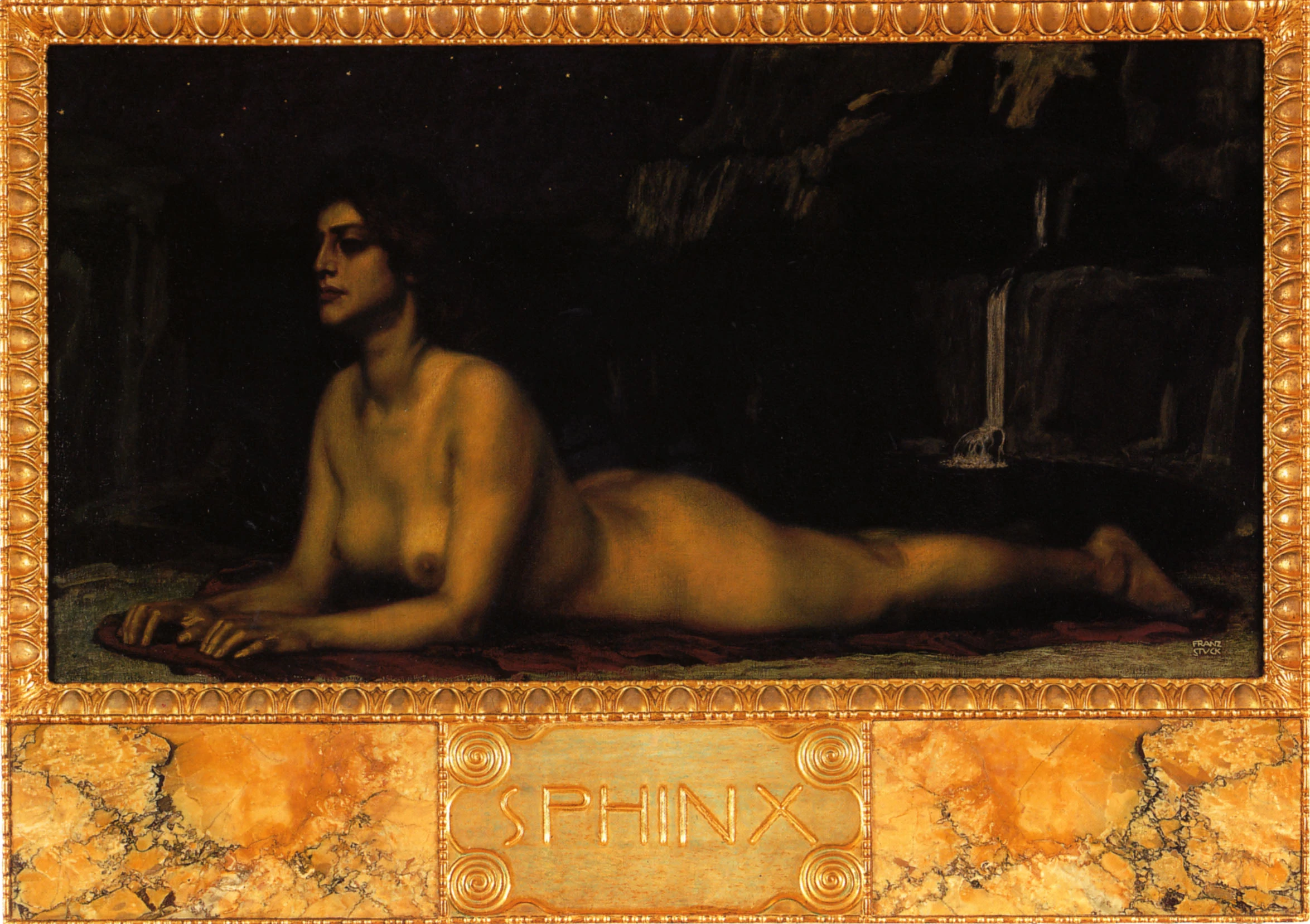

This is, of course, a tragedy. For centuries framing has been a fascinating and deep discipline with its own fashions, trends, techniques and philosophies. It is the art that art lives in, the clothes the paintings wear. The style and craft of a painting’s frame holds invaluable information about how the culture that owns the art, thinks about it. For example, the simple, somber portraits of 17th century puritans were framed in simple black wood, a direct rejection of the flamboyant gilded filigree that wreathed the icons of Roman Catholic saints. Frames are a dialog happening in parallel to the artwork.

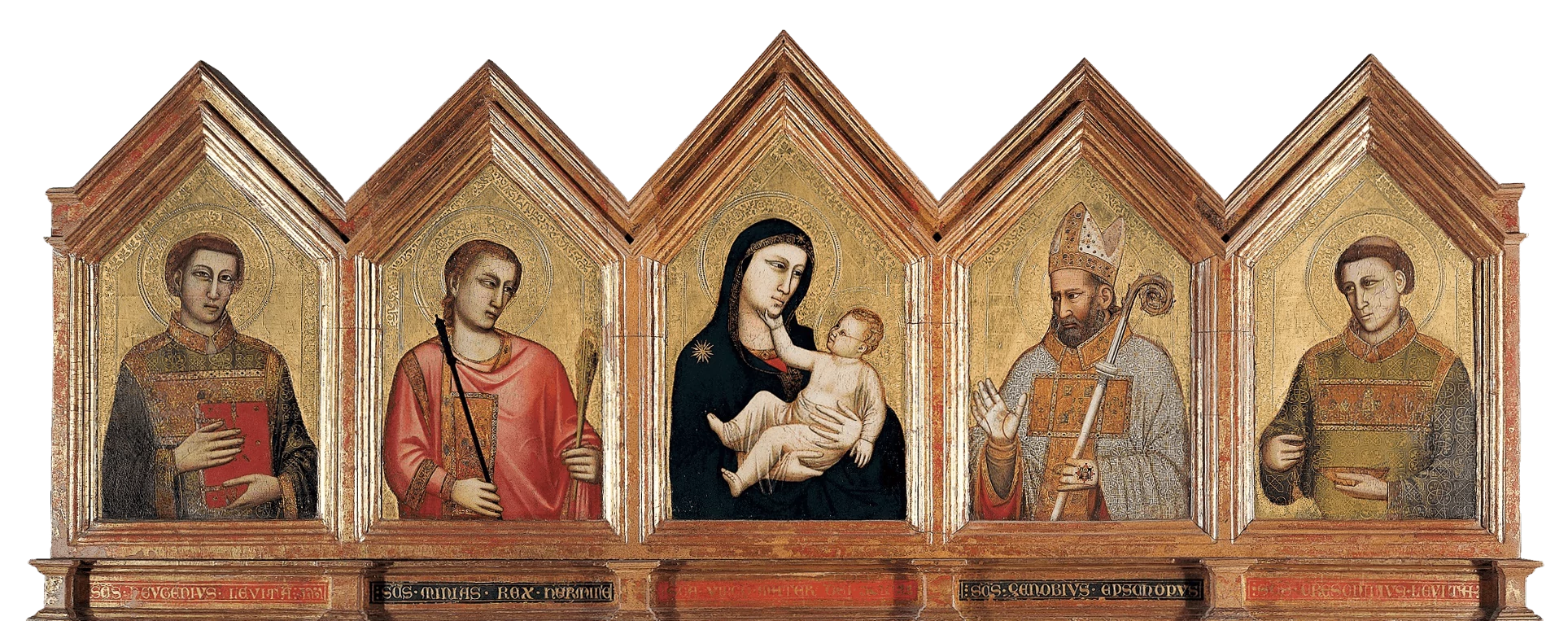

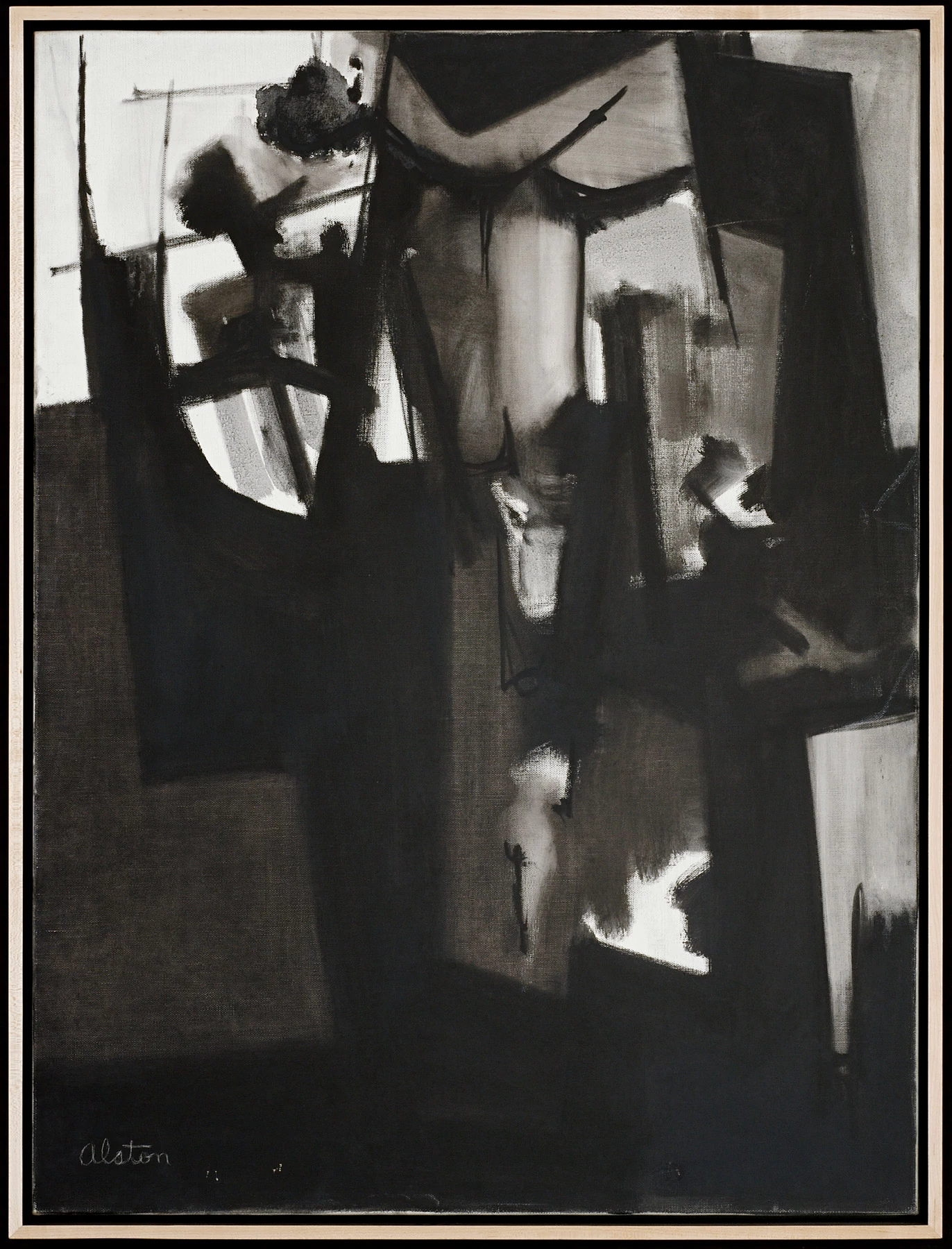

I hope, someday, to dig deeply into the history of framing artwork, but until then, I recommend visiting the brilliant and impossibility deep rabbit hole that is The Frame Blog, a long-running blog and research partnership between historian and archivist Lynn Roberts and the National Gallery of London. Incredible stuff, definitely check it out. And below, you can find those rare selections of the Obelisk library that have retained their frames, from the beaded and columned mounting of the Fiesole Altarpiece to Florine Stettheimer’s trumploi curtains pulled back to reveal the scene, to a Frida Khalo self-portrait ringed with mirrors that confront the viewer with their own gaze—these frames are often incorporated into the artwork to the point where they are inseparable.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Framed Artwork? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.