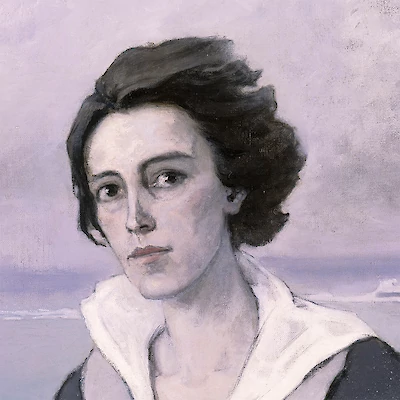

Romaine Brooks

Powerful women in shades of gray

1874 – 1970I was traveling in Switzerland with Ida Rubinstein when War was declared. Reluctantly my mind returns to those four years of intense mental strain and to the many incidents that were or were not relevant to those tragic times.

On our way back to Paris Ida was very agitated. She spoke of her future, of her career. She had passed the night on her knees praying God to avert this calamity, she said. I remember being more indignant than anything else. how was it possible that presumptuous man failed again and again to avert those mass-suicides, which Nature thrusts upon him periodically. Surely it was no mere question between angry Nations but of Nature adjusting man’s mistakes. My philosophizing over birth-control brought no response from Ida who was lost in the tragedy of the moment.

As I was strongly against the war, on returning to Paris, set myself to working hard at my painting; but of course this attitude proved impossible to keep up and soon along with everyone else I was doing all I could do to help. My efforts were more especially directed towards the French artists, and one of my most precious belongings is a small bronze plaque especially engraved which they presented to me. Indirectly because of the war my income from America had stopped, so I sold some personal valuables in order to present a small donation to be named after a fallen artist-soldier. The proceeds of this fund were eventually given to the blind soldier Lemordant. I wanted to join a unit at the front and tried to harden myself by driving an open oar during an unusually cold spell. This effort sent me to bed with pains in my back and later to Aix-lea-gains for a treatment.

I can see myself seated in the black and crystal terrace watching the zeppelins as they direct their course towards the Eiffel Tower; the terrific bombing reminding me that is is no mere play.

It came to me as a surprise that not one of my servants was French. They all began to hate each other thoroughly and to fight among themselves. I feared them more then a whole battalion of German soldiers. My cockney chauffeur and my Alsatian maid were particularly hostile. She confided to me that when her German brother, whom she loved, entered Paris with his regiment she would run out into the street and embrace him even though her husband was a Frenchman. The Spanish concierge could now only speak in her own language. The over-polite Belgian chef apparently hated them all alike - allies included, and while bowing to me over and over again, as he backed out of the room, he hurled imprecations upon all the personnel of the household.

I inaugurated with my friend Natalie Barney my newly whitewashed cellar. Bird, the cookney chauffeur seated near-by was armed with a pickax, “To dig you out M'm” he explained. Than when terrific thuds of bombing shook the very ground, to reassure he would invariably say “Barrage M'm!”

I was in my bath-tub when the first Big Berthe fell. It was evident that some new terror was upon us. After dressing quickly I left the house to keep a luncheon appointment, but it was too early so I ventured my way towards the Trocadero Gardens opposite. There a few people were silently walking about as if in a dream. All was in suspense and to catch an eye was to reciprocate a look of apprehensive enquiry.

On reaching the restaurant I was directed to a table in the rear, as far as possible from the large glass-windows. One of our friends was missing; so after luncheon we went to seek her at her flat. No one answered the bell, and as we stood waiting in the courtyard undecided what to do, a door leading into the cellar opened and there stood before us a strange figure. It was clad in on old grey wrapper with bed-room slippers, hair covered with cobwebs and a rusty lantern dangling from a string tied round the neck. One hand grasped a valise and the other a time-table. We recognized our friend. On hearing the Big Bertha she had retreated to the cellar along with everyone else in the building. It certainly was no time for mirth yet we all laughed just the same.