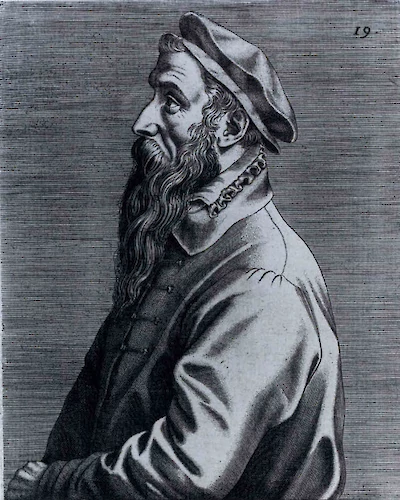

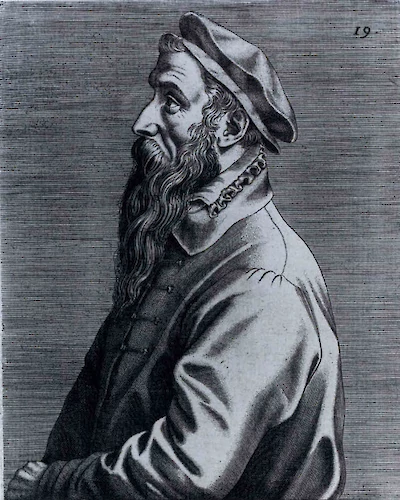

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The peasant life is the humanist ideal

Pieter Bruegel painted in the midst of a cultural tornado that swept Western Europe in the 1500s. The power of the Catholic church was eroded by the humanism and intellectualism that spread from Italy’s High Renaissance and the new Protestant reformation. Bruegel’s early work was an almost perfect mirror of the demonological themes that Heironymus Bosch had pioneered and had become wildly popular throughout the Netherlands. Birds-eye views of battles between angels and fish-faced demons—Bruegel leaned into the religious obsessions of his culture.

In 1565, Bruegel turned 40 and found a new focus. After traveling to Italy, Antwerp, and finally settling in Brussels, Bruegel decided to paint people. Influenced by the growth of ‘heretical’ Calvinism or by maturing his aesthetic subject matter, Bruegel began to dress as a peasant and socialize at rural weddings and festivals. His work changed dramatically, focusing on the seasons and the honest toil of the working classes.

Bruegel was the first in a dynasty of Flemish painters, and is one of the clearest examples of the role of artists evolving from conduits for religious dogma to independent interpreters of culture. His sons Peiter and Jan Bruegel took up the brush after him, though they were young when their father died, and their work never achieved the refinement and pragmatic worldview of their father’s final works.