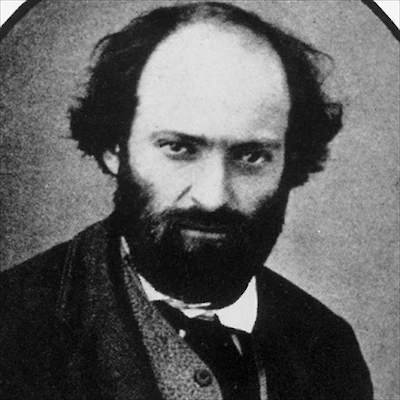

Paul Cézanne

A lifelong struggle to capture the intensity of life

1839 – 1906Paul Cézanne To Émile Zola

Aix, July 29 1858

Mon cher,

Not only did your letter make me happy, getting it made me feel better. I’m gripped by a certain internal sadness and, my God, I dream only of that woman I told you about. I don’t know who she is; I sometimes see her out in the street as I’m going to the monotonous college. I sigh, morbleu, but sighs that do not give themselves away, these are mental sighs. I thoroughly enjoyed that poetic morsel you sent me, I really liked to see you remember the pine that provides shade for the riverbank of the Palette, the pine that I love, how I should like to see you here – damn everything that keeps us apart. If I didn’t restrain myself, I should let off a whole string of nom de Dieu, de Bordel de Dieu, de sacrée putain, etc; but what’s the point of getting in a rage, that wouldn’t get me any further, so I put up with it.

Yes, as you say in another piece no less poetic – though I prefer your piece about swimming – you are happy, yes you [are] happy; but I suffer in silence, my love (for it is love that I feel) will not come bursting out. A certain ennui is always with me, and when I forget my sorrow for a moment it’s because I’ve had a drink. I’ve always liked wine, but now I like it more. I’ve got drunk, I’ll get drunker, unless by chance I should succeed, my God! I despair, I despair, so I’m going to deaden the pain.

P Cézanne

Émile Zola to Paul Cézanne

Paris, March 25 1860

Mon cher ami,

You must make your father happy by studying law as assiduously as possible.

But you must also work hard at drawing – unguibus et rostro [tooth and nail]. As for the excuses you make, about sending engravings, or the supposed boredom your letters cause me, allow me to say that that is the height of bad taste. You don’t mean what you say, and that is some consolation. I have only one complaint, that your epistles are not longer and more detailed.

I await them impatiently, they make me happy for a day. And you know it: so no more excuses. I’d rather stop smoking and drinking than corresponding with you.

Then you write that you are sad: I reply that I am very sad, very sad. It’s the wind of time blowing around our heads, no one is to blame, not even ourselves; the fault lies in the times in which we live. Then you add, if I understand you, that you don’t understand yourself. I don’t know what you mean by the word understand. This is how it is for me: I saw in you a great goodness of heart, a great imagination, the two foremost qualities before which I bow. And that’s enough; from that moment on, I understood you, I judged you. Whatever your failings, whatever your errings, for me you’ll always be the same … What do your apparent contradictions matter to me? I’ve judged you a good man and a poet, and I shall go on repeating: “I have understood you”. Away with sadness! Let’s end with a burst of laughter. In August, we’ll drink, we’ll smoke, we’ll sing.