Monogrammist GZ or Gabriel Zehender

Dueling identities

It’s incredible how much we know about artists who died hundreds of years ago. A surprising number of civic records, critical commentary, letters to and from artists, early histories, even receipts from commissions survive, allowing historians to reconstruct robust profiles of many of history’s artists. But sometimes we're not so lucky. Artists can slip through the cracks, leaving behind only a handful of works and only the faintest historical footprint.

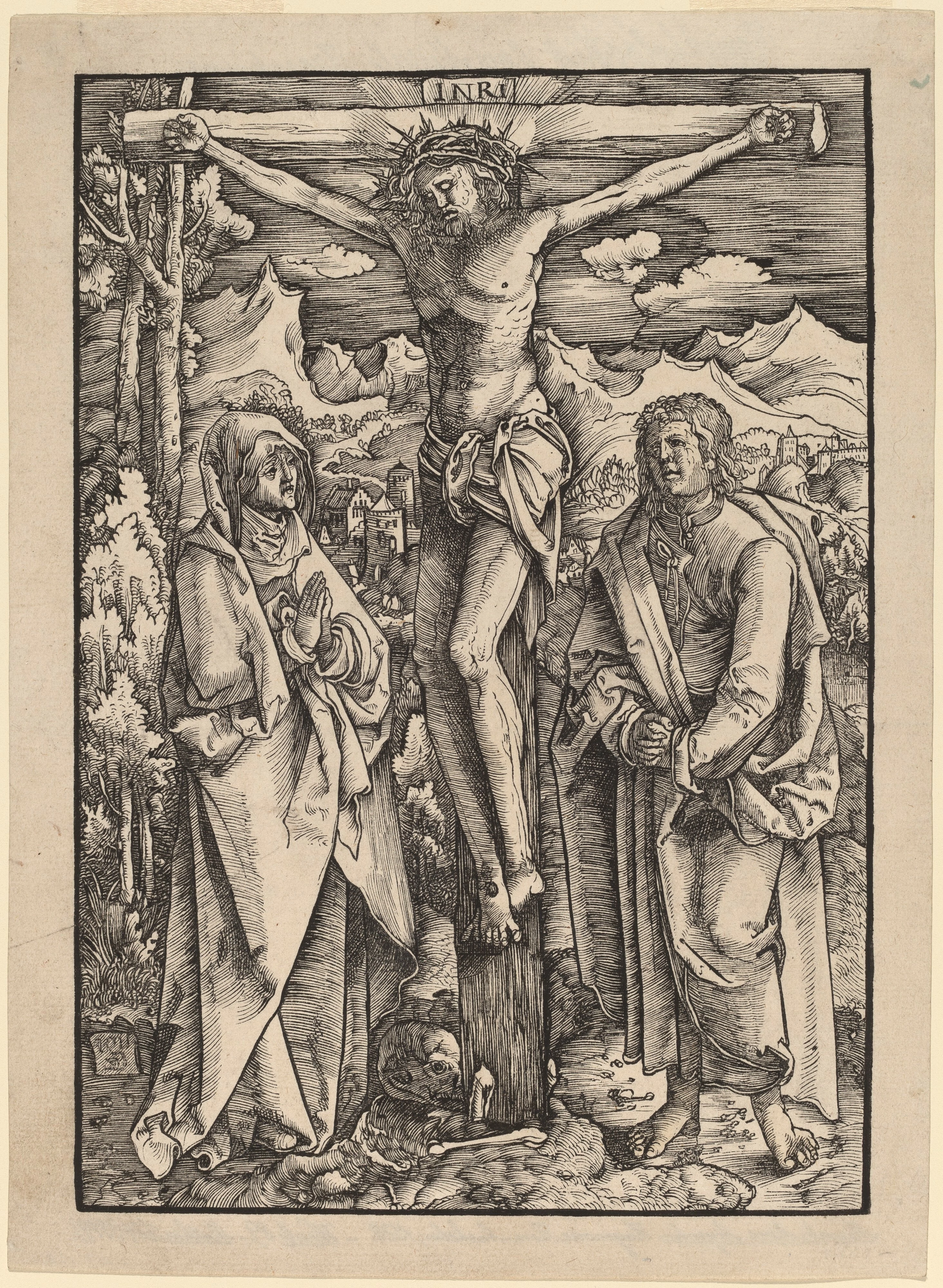

Two small but remarkable woodcut prints live in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a Crucifixion and a double portrait of Saint Thomas and Saint Bartholomew. Each print is rendered in the hyper-detailed style developed in the 15th century by artists like Albrecht Durer, made possible by painstaking inscription of the negative image on polished blocks of fruit wood, inked with finely ground lampblack mixed to transfer the delicate marks. These prints, along with a quick, but surprisingly emotional pen and ink sketch of the Madonna in Mourning, were created between 1518 and 1521, and are attributed to a mysterious artist known only as Monogrammist G.Z.

The works associated with G.Z. were included as illustrations in publications printed in Basel, Strasbourg and Hagenau, and show the influence of artists of the Danube school of painters and the Strasbourg printmaker Hans Baldung Grien, one of Durer’s most successful students. Other than the timeframe and association with the Upper Rhine region, we know little else about the artist behind these works.

But historians are persistent hunters of detail, and for more than 100 years they've been attempting to resolve G.Z.’s anonymity. As far back as 1852 the historian Georg Kaspar Nagler suggested that G.Z. was one and the same as an obscure Polish-born (Groß Mausdorf) artist working in Basel named Gabriel Züge (also Züger, Zaunder, or Zehender). The first documentation of Zehender appeared in 1529, when he was registered with Basel’s guild of painters and granted Swiss citizenship. Zehender was active until at least 1535, when Basel town records show him listed as a fugitive from the law. This theory remained popular, with support from the German historian Gert von der Osten in his 1957 article Zwei Bildnisse von Gabriel Zehender? saying“I would like to agree with the reference to the upper Rhine and suggest a Basel painter’s name that has only recently risen from oblivion: Gabriel Zaunder.”

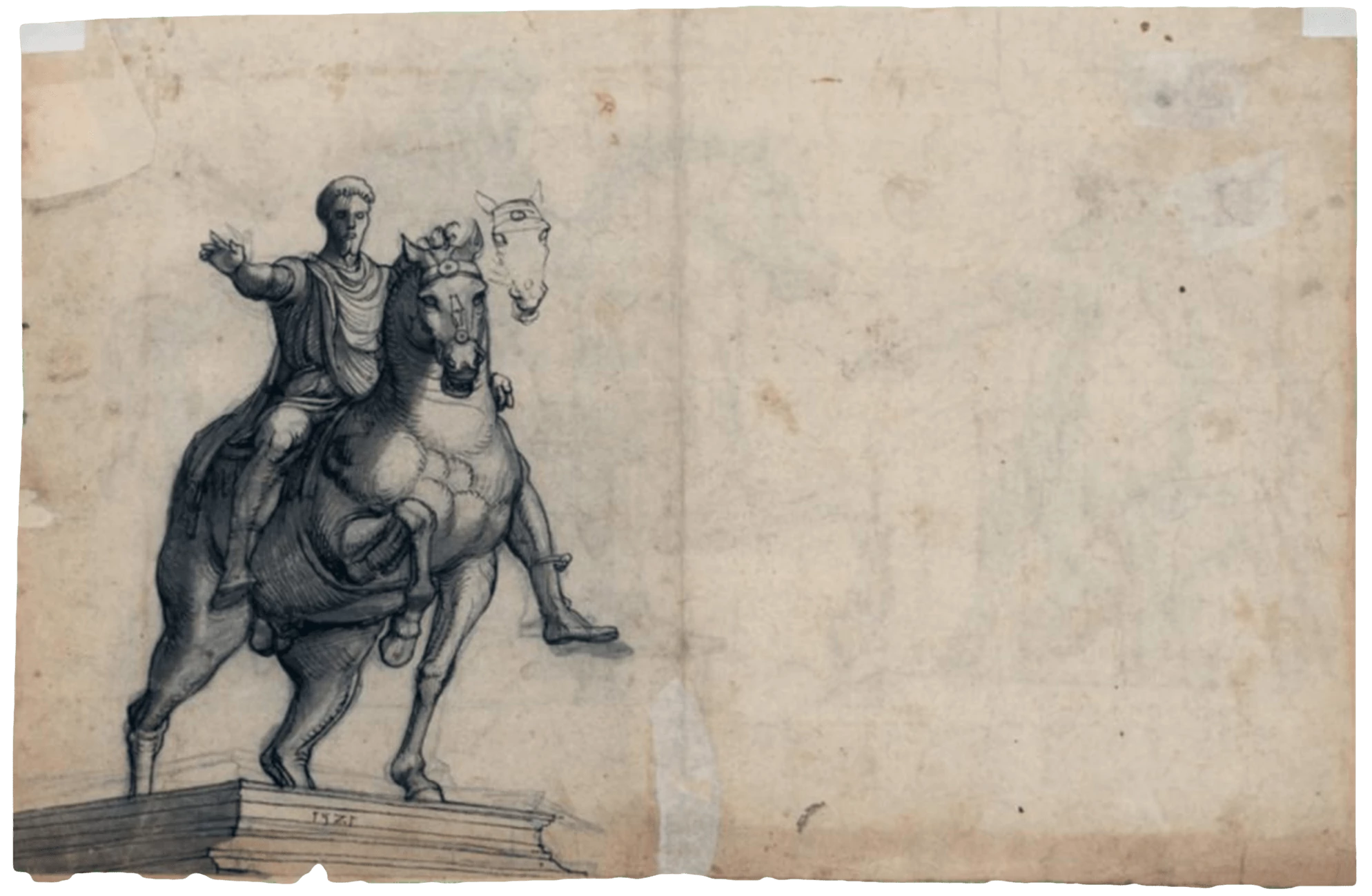

Aside from the obvious matching initials, it’s a sensible triangulation, with Nagler and Von der Osten, taking into account local artistic influences on Zehender’s work to place him in the locations where monogrammist G.Z. was published and vice versa. But like most art history mysteries, this topic is firmly in the academic combat zone, and the synthesis of these two artists was contested in 2021 by Dürer specialist and Chief Curator at Vienna’s Albertina Museum, Christof Metzger. In his passionate and vivid article Alle Wege führen nach Rom, (all roads lead to Rome), Metzger uses a little-known sketch by G.Z., Three views of Marcus Aurelius’s Equestrian Monument, to place G.Z. in Rome in 1521, and refers to the coniferous wood used in the panel for a boldly colored double portrait of a married couple, (the Upper Rhine region preferred deciduous) to argue that G.Z. never returned to Basel, splitting their career trajectory and work from that of Zehender.

And now a caveat before some unearned speculation. The source materials I've referenced above are in German, a language I do not speak, leaving me to Google Translate my way toward understanding. Additionally, attributions to G.Z. vs Zehender often contradict or conflate the scholarship I've been able to dig up so far. The double portrait, for instance, is attributed to Zehender by Georg Kaspar Nagler, attributed to G.Z. by Christof Metzger, and to Zehender-as-G.Z. by the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, where the painting currently resides. Little wonder the ever-pragmatic British Museum’s entry on G.Z. simply states: “His identification with the Basel painter Gabriel Zehender, whose activity is recorded in documents of 1527-35, has never been confirmed.”

...

Now let’s take a break from historial deep dives and refresh ourselves with a little formal analysis. Today, of the scant few artifacts ascribed to G.Z. and Zehender’s, there are two crucifixion prints, one attributed to each artist. Both prints are variations on an extremely common motif of the day, the crucifixion of an exicated Christ with Mary and John at the foot of the cross. Both prints show distinct similarities to Albrecht Durer’s 1511 woodcut The Crucifixion, and Christ on the Cross with Mary, John, the Magdalen, and Stephen by Hans Baldung Grien—with similar overall composition and repeating iconographic elements like the skull at the foot of the cross.

But the two works by G.Z. and Zehender carry similarities that separate them from previous iterations of the genre. In both, a striking mountain range slices across the background, and each image is framed by a tree on one side. But there are differences in the way Christ holds his thumbs, the way John places his feet. And the quality is different too. The earlier print, attributed to Zehender, is rendered with less detail and its human forms are more crude—check out Christ’s scrawny arms and shapeless torso. Is this a single artist improving over time, two artists of different skill, or an irrelevant artifact of different woodcutting specialists who transferred the drawings to the block with varying degrees of sensitivity? What do you think? Take a look at these two crucifixions, really zooooom in. And let me know in the Discord chat what you find.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Monogrammist GZ or Gabriel Zehender? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.