Luigi Russolo

Machines that scream: inventing Futurist music

Music was Luigi Russolo’s birthright. His father was a cathedral organist, and his brothers graduated from the Milan conservatory. In school, Russolo pursued painting, but as a mature artist he returned to music and transformed it into a dissonant beast, inciting riots from crowds, inventing new instruments and becoming the father of noise music.

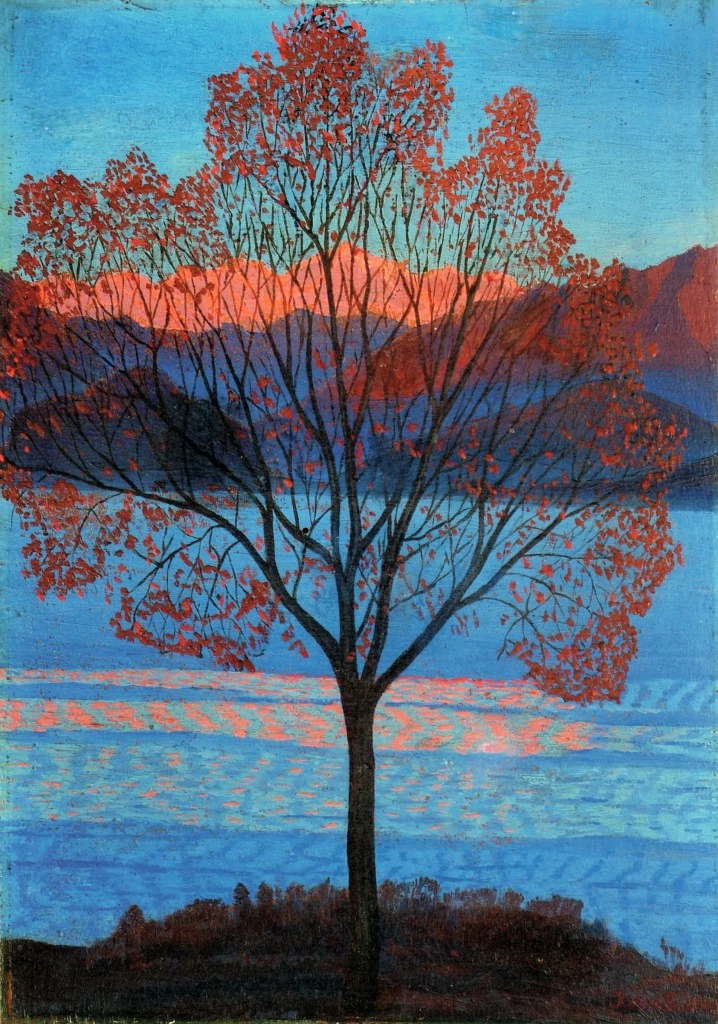

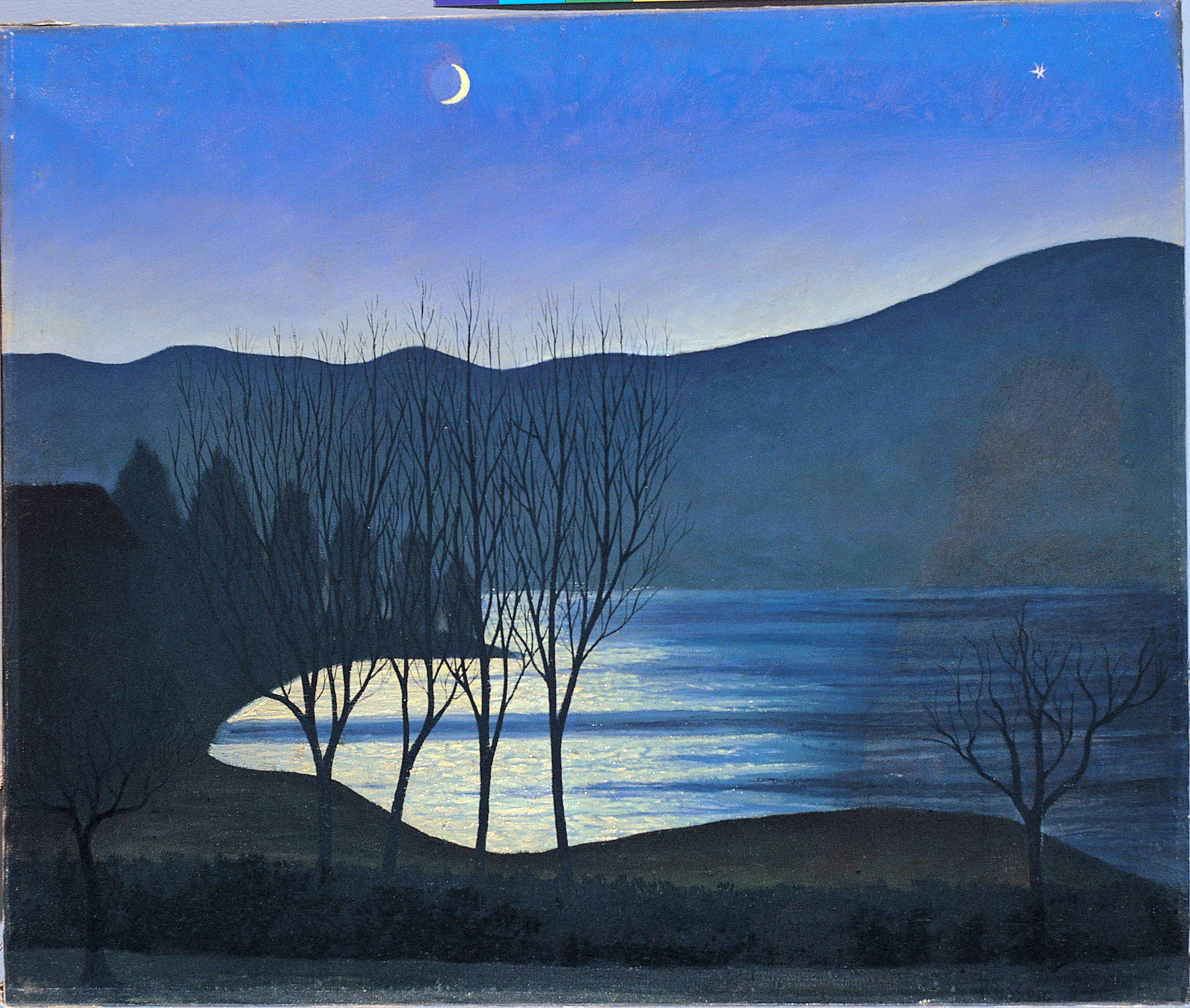

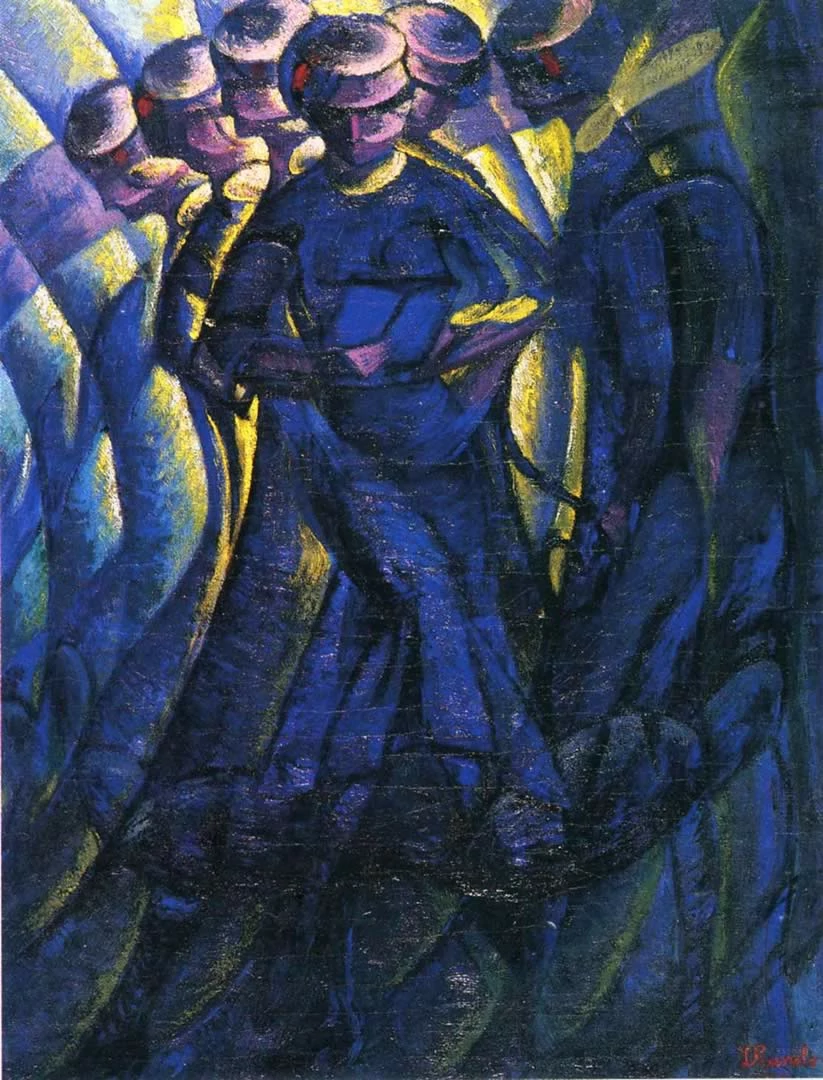

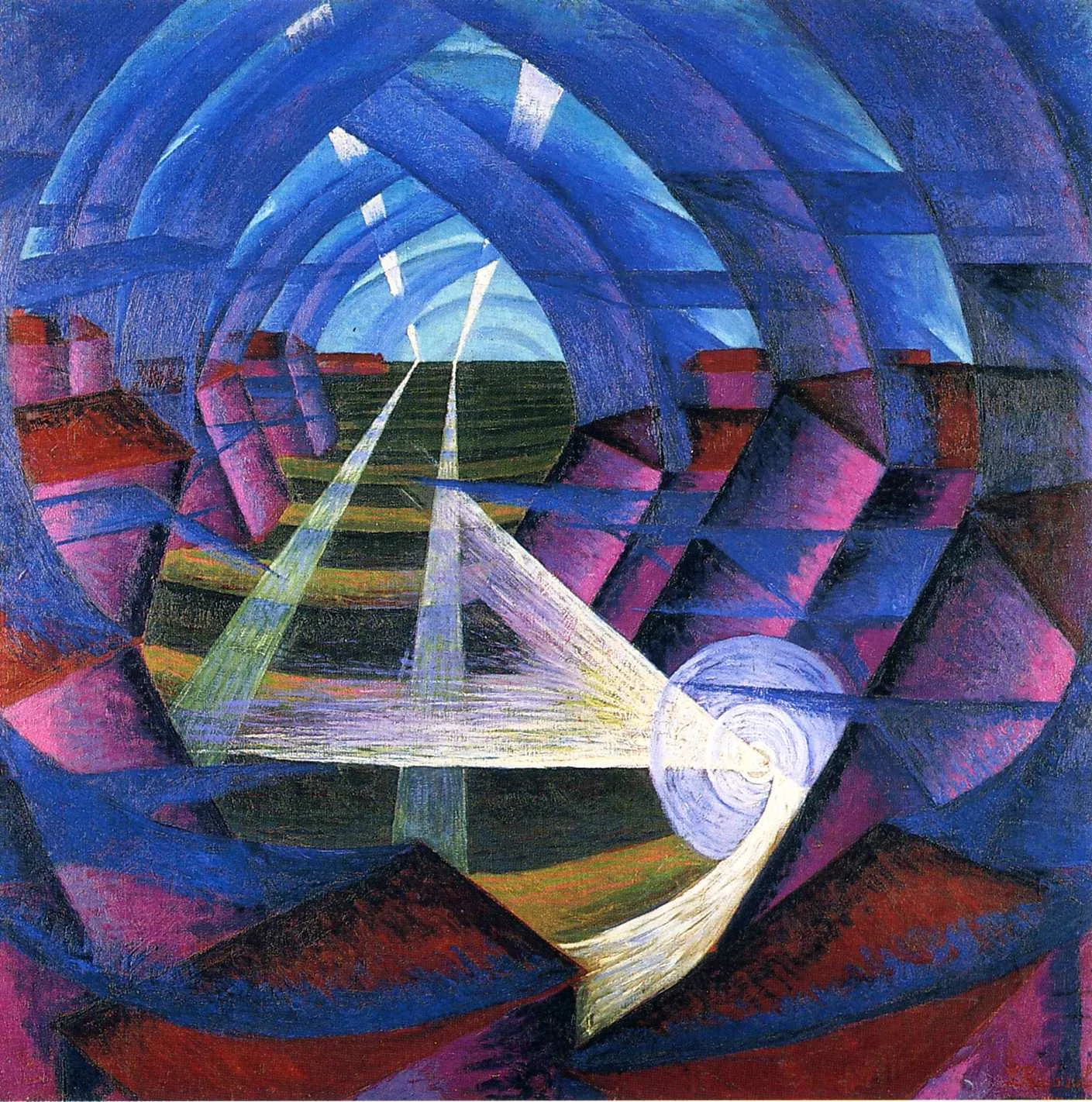

During his studies in the Milanese art school, Accademia di Brera, Rullolo worked in a chilly, symbolist style. His early work shows a crisp attention to detail and a preoccupation with landscapes bathed in dramatic lighting. During his time at the Accademia, Rullolo joined the Famiglia Artistica di Milano, a group of young painters developing a new way of making art. The group included Carlo Carrà and Umberto Boccioni, who, together with Russolo went on to draft the foundations of a new movement devoted to speed, violence and the beautiful brutality of the machine: Futurism.

By 1910, Italy was boiling. Filippo Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto had been published the year before, radicalizing the Italian avant-garde in a mission of patriotic destruction and violence, and Russolo was in Futurism’s spinning center. His friendship with Carra and Boccioni put him in the inner circle of the new movement. He took part in the serata, theatrical Futurist dinner parties featuring angry poetry and flag burnings, and signed both Marinetti’s manifesto and Boccioni’s Manifesto of Futurist Painting.

A few years later Russolo had a revelation while listening to a performance of his friend Balilla Pratella’s Futurist orchestra in Rome’s Costanzi Theatre. The history of sound appeared in his mind as an evolution culminating in the triumphant dominance of mechanical noise. In a letter to Pratella, he drafted his seminal work “The Art of Noises,” a futurist manifesto of sound. “Ancient life was all silence. In the nineteenth century, with the invention of the machine, Noise was born. Today, Noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibilities of men.”

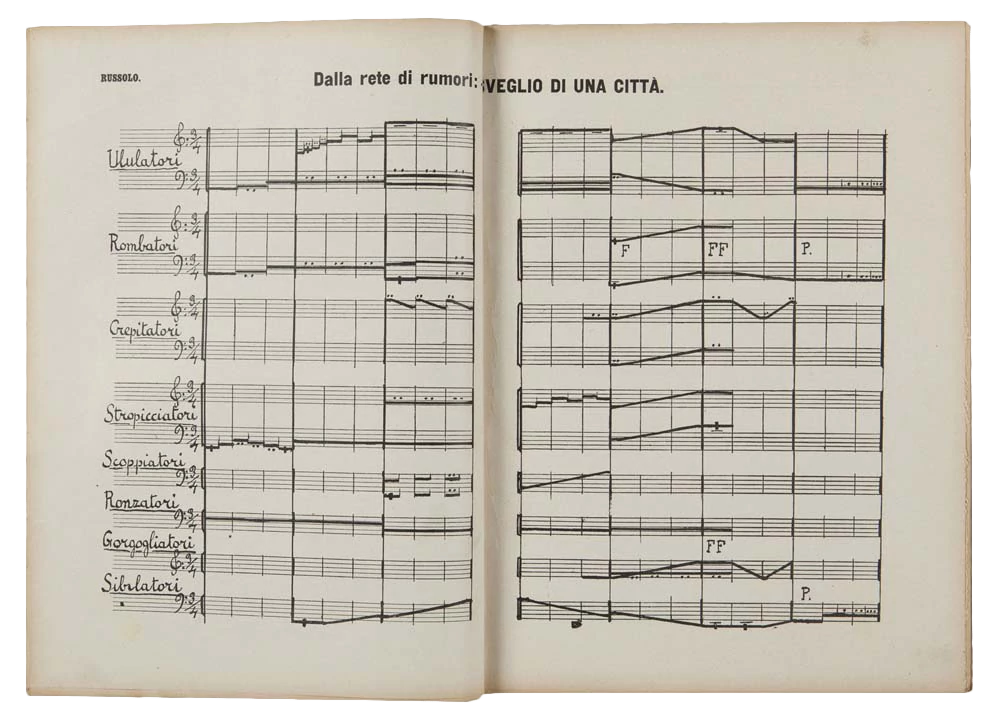

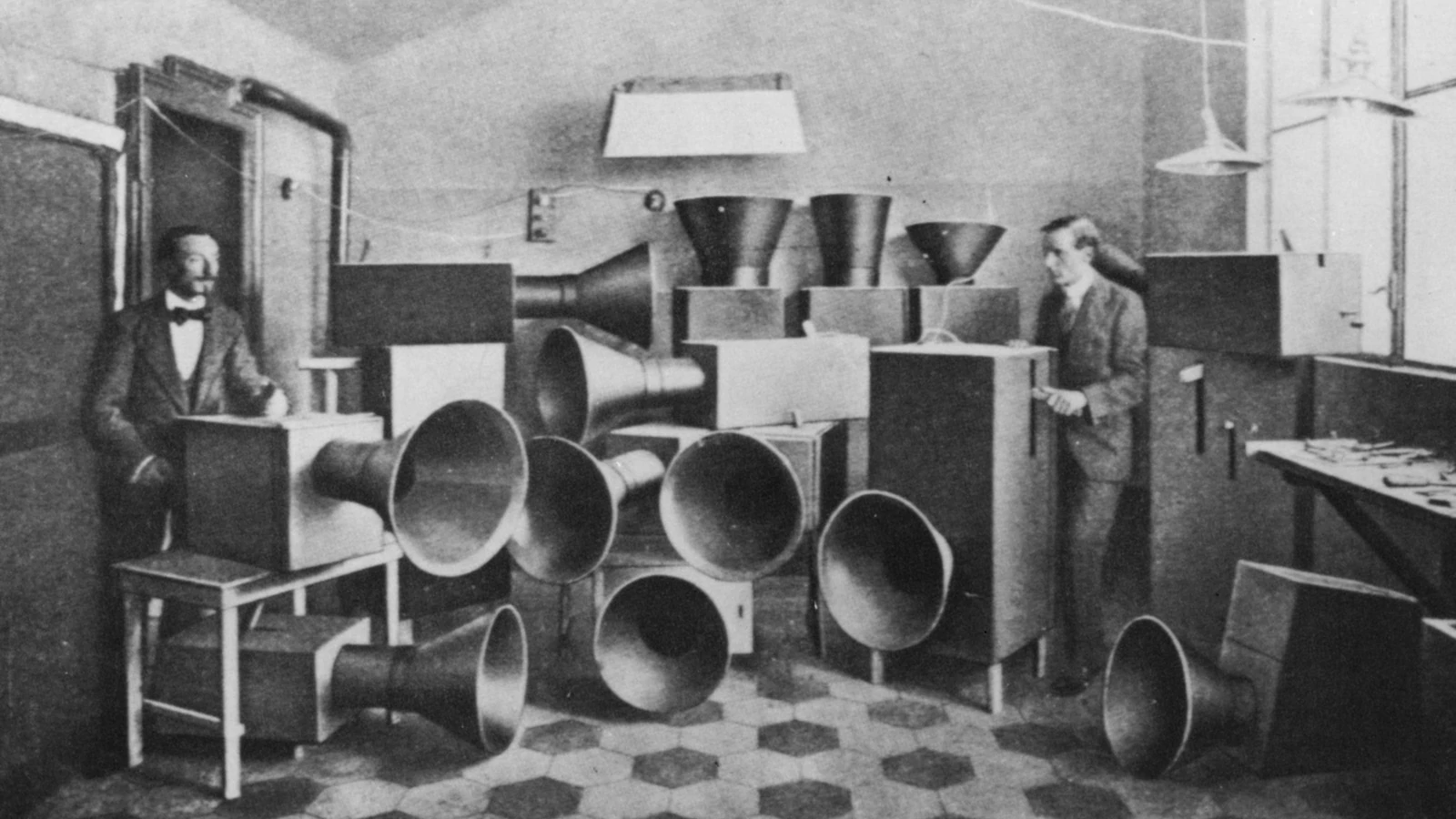

Luigi Russalo’s new music required new instruments, and over the next ten years, Russalo invented a zoo of homemade instruments he called Intonarumori. A shambling crowd of mysterious boxes and conical horns mounted with hand-cranks and mechanical workings to create his new vocabulary of sounds:

The Intonarumori were played in Futurist concerts during 1913 and 1914, earning both praise and violent hostility. The next decade saw Russolo continue his performances and develop new musical notation, despite an injury sustained in World War I. By 1921 his music was recognized and respected by the great russian composer Igor Stravinsky, and Sergei Diaghilev, the founder of the famous Parisian Ballets Russes.

Russolo’s machines burned in the Paris bombings of World War II, and the only recording of his machines was made by his brother Antonio in 1921, combining the cacophonous noises with a conventional orchestral score. Though his work has disappeared, Russolo’s dramatic expansion of the musical vocabulary has stuck with us. From experimental noise music to the iconic thunder of the Inception soundtrack—we owe a nod to Luigi Russolo.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Luigi Russolo? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

Ancient life was all silence. Today, Noise reigns supreme over the sensibility of men.