Henri Matisse

100% artist

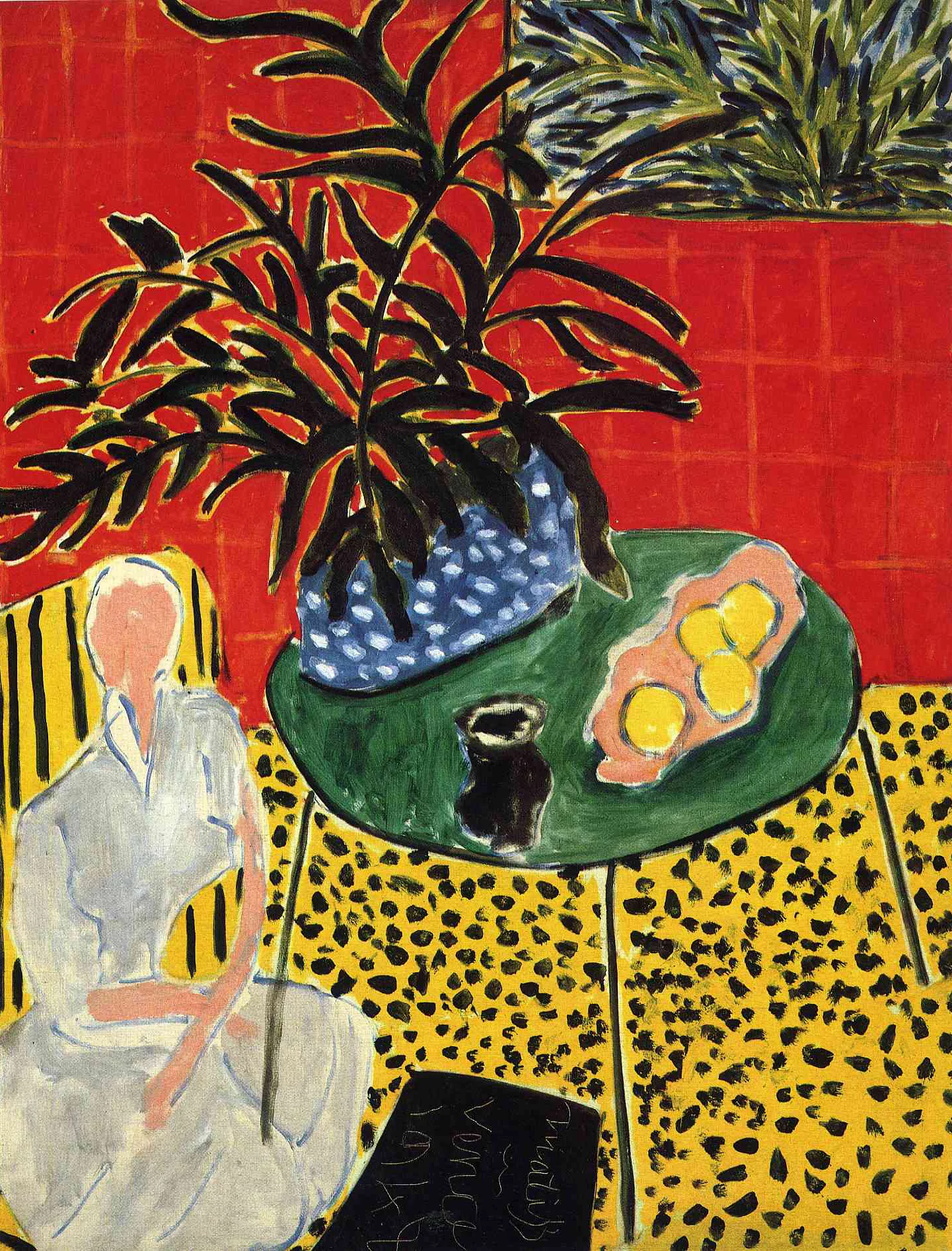

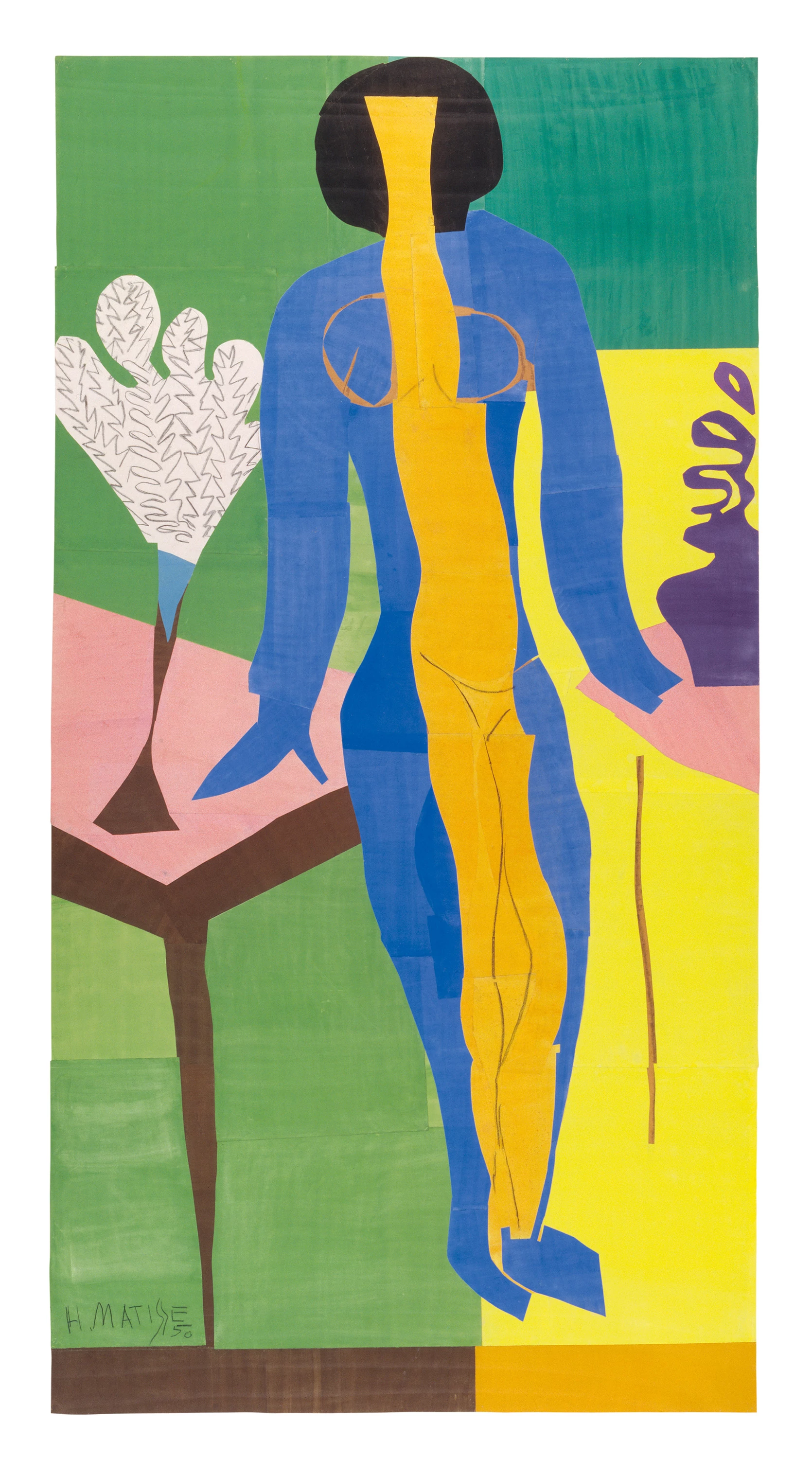

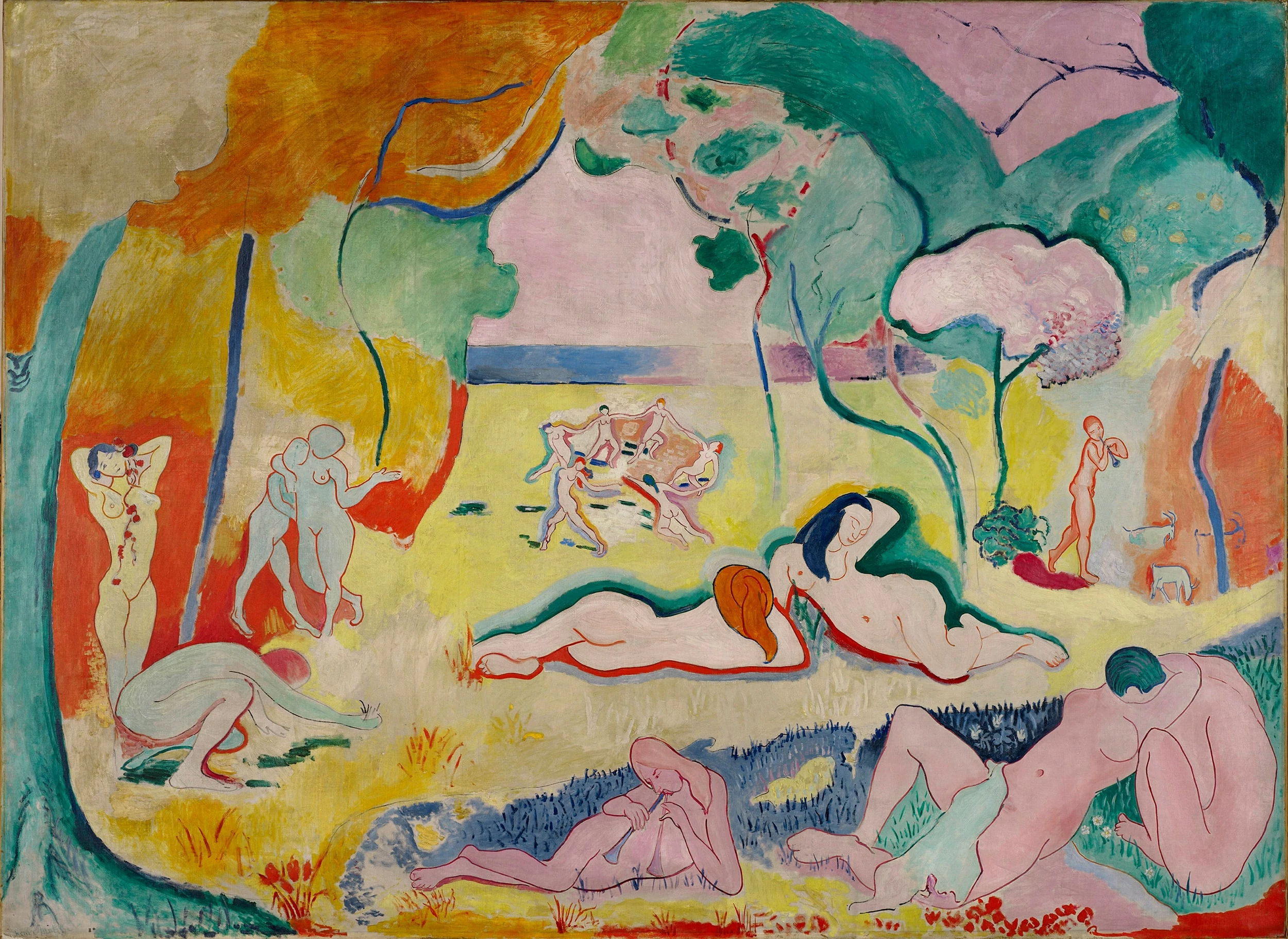

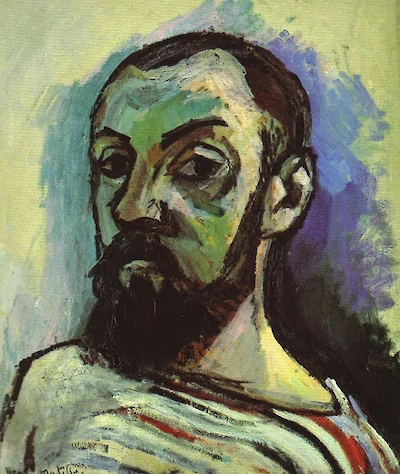

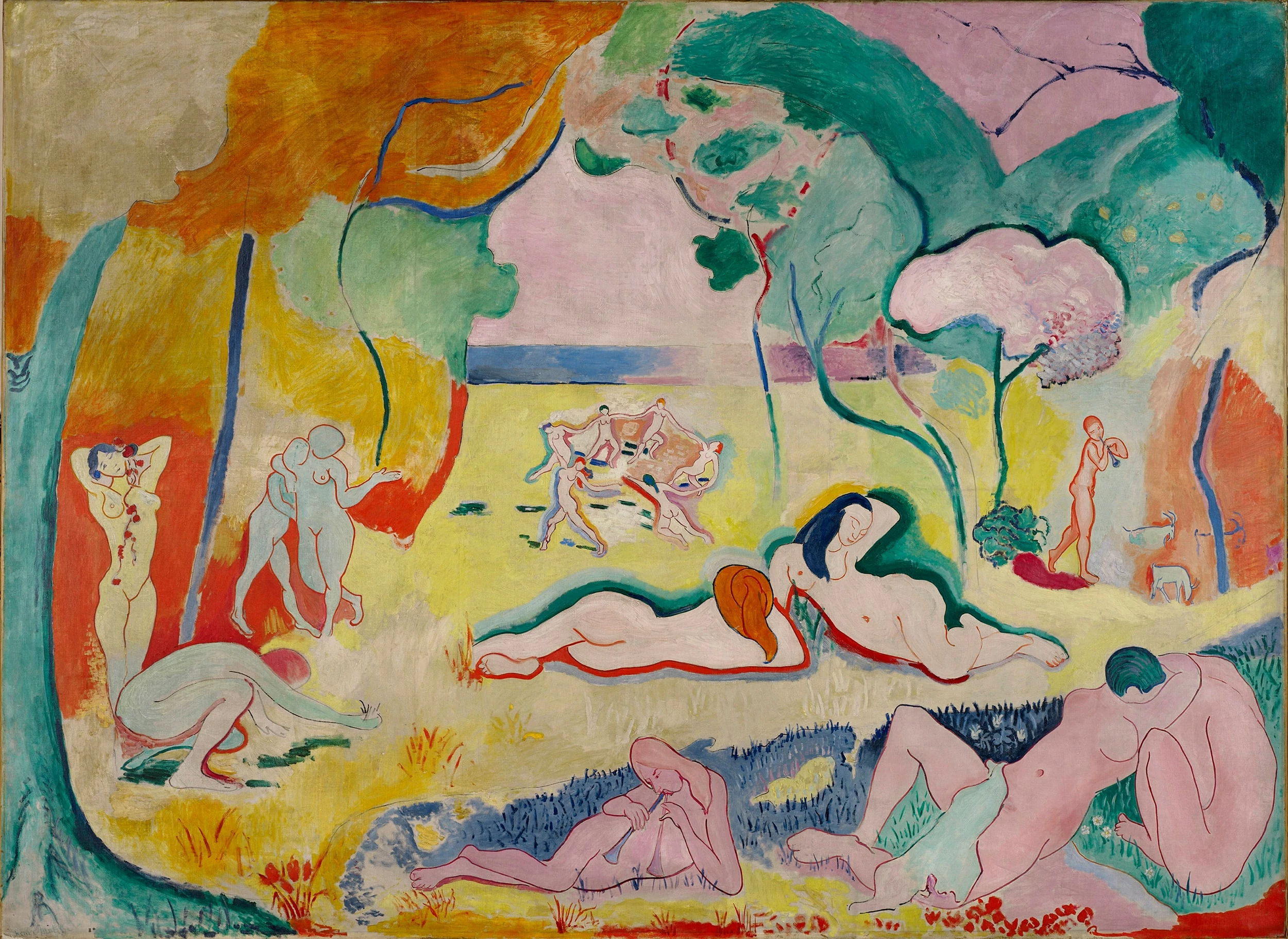

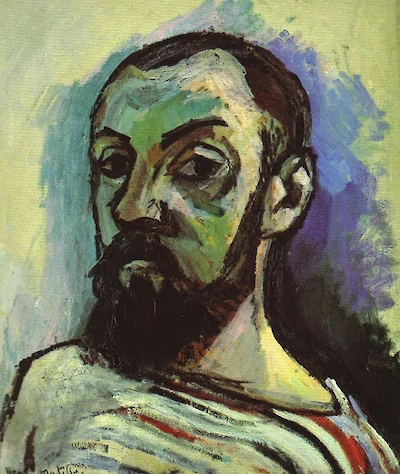

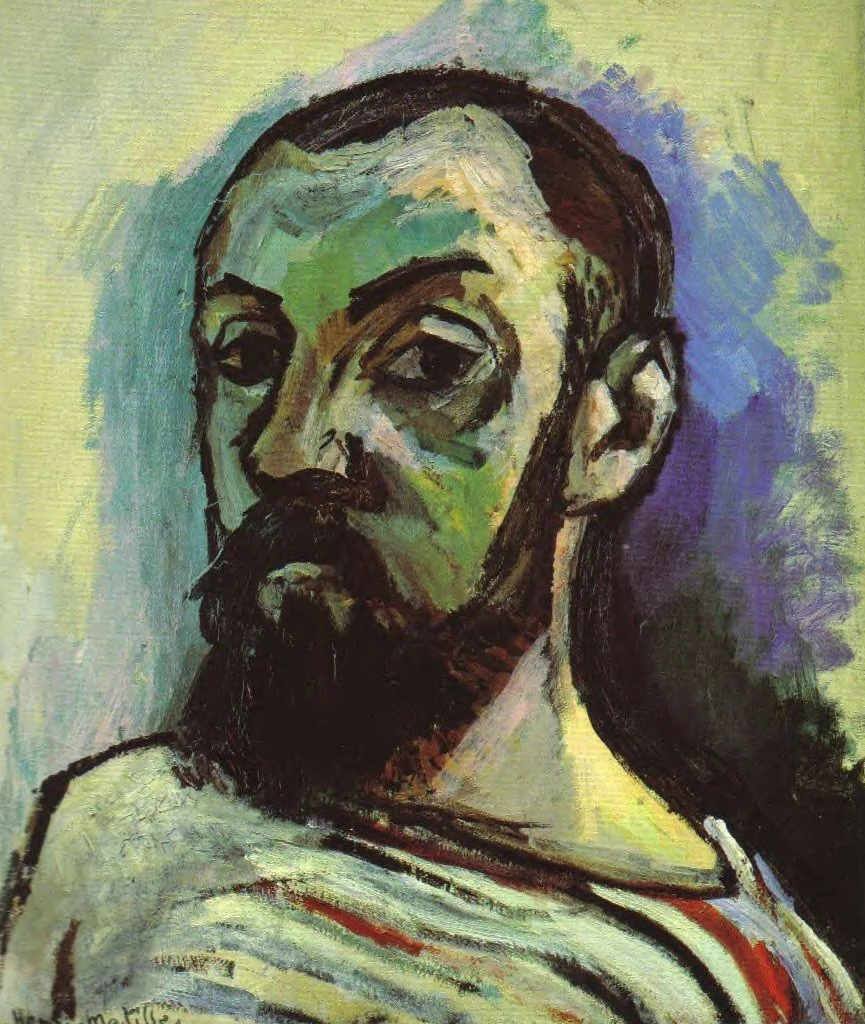

Henri Matisse started as a bad painter. In fairness this is the case for most artists, but it feels particularly important to note with Matisse, who is considered along with Pablo Picasso as one of the fathers of modern art. At his height, Matisse created staggering work that reinvented color itself. From the founding of the Fauvist movement, to the radical collapse of physical space in the Red Room, to the poetic primitivism invoked by Dance (II), it’s rare to find yourself in front of a Matisse artwork that doesn’t kidnap your eyeballs and transform reality in front of you. But first, he was terrible.

Matisse was a clerk. The son of a grain merchant, he’d landed a solid job in Paris, on track for a lucrative career in law. But at 19 he got appendicitis, and (like Frida did nearly 40 years later) took up painting to occupy himself during convalescence. These first works changed something in young Henri, who later described it as discovering “a kind of paradise.” He promptly abandoned law and bought more paint. And he did have some immediate skill with a brush. Still lives, in the dour Dutch tradition, were among his first attempts dated to 1890. Over the next few years he increased his scope, tackling interior spaces, people, and the occasional garden view and seascape. What I appreciate about those early works is how despite Henri’s clear passion and dedicated practice, they are still utterly drab and lifeless. There is so little joy and mystery—that came later. While some artists seem to burn their youth into their work, creating some of their most raw and impactful pieces as teenagers (often before dying in their 20s), what a relief it is that one of the most famous and influential artists in history had to get through years of uninspired work to get to the good stuff.

Though a bit of a late-starter by academic standards, Matisse got placement in some superb schools, working under William-Adolphe Bouguereau at the Académie Julian and in the studio of Gustave Moreau at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Inspired by these renowned teachers, and artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Nicolas Poussin, Antoine Watteau, the then radical Édouard Manet, and by the woodblock prints trickling in from trade with Meiji Japan. We get a sneak peek at Matisse finding something new in 1896, in his work Rochers a La Belle Ily, a startlingly colored view of the sea between flattened, red-smeared cliffs. It’s a quick sketch painted in situ at the home of John Russel, a painter who introduced Matisse to both color theory and the work of Vincent Van Gogh. From here Matisse evolves steadily, swapping out his earth tones for bright oranges and greens, his brushstrokes loosen, and his spaces flatten. The paint itself joins the landscape or figures as the subject matter of the artwork.

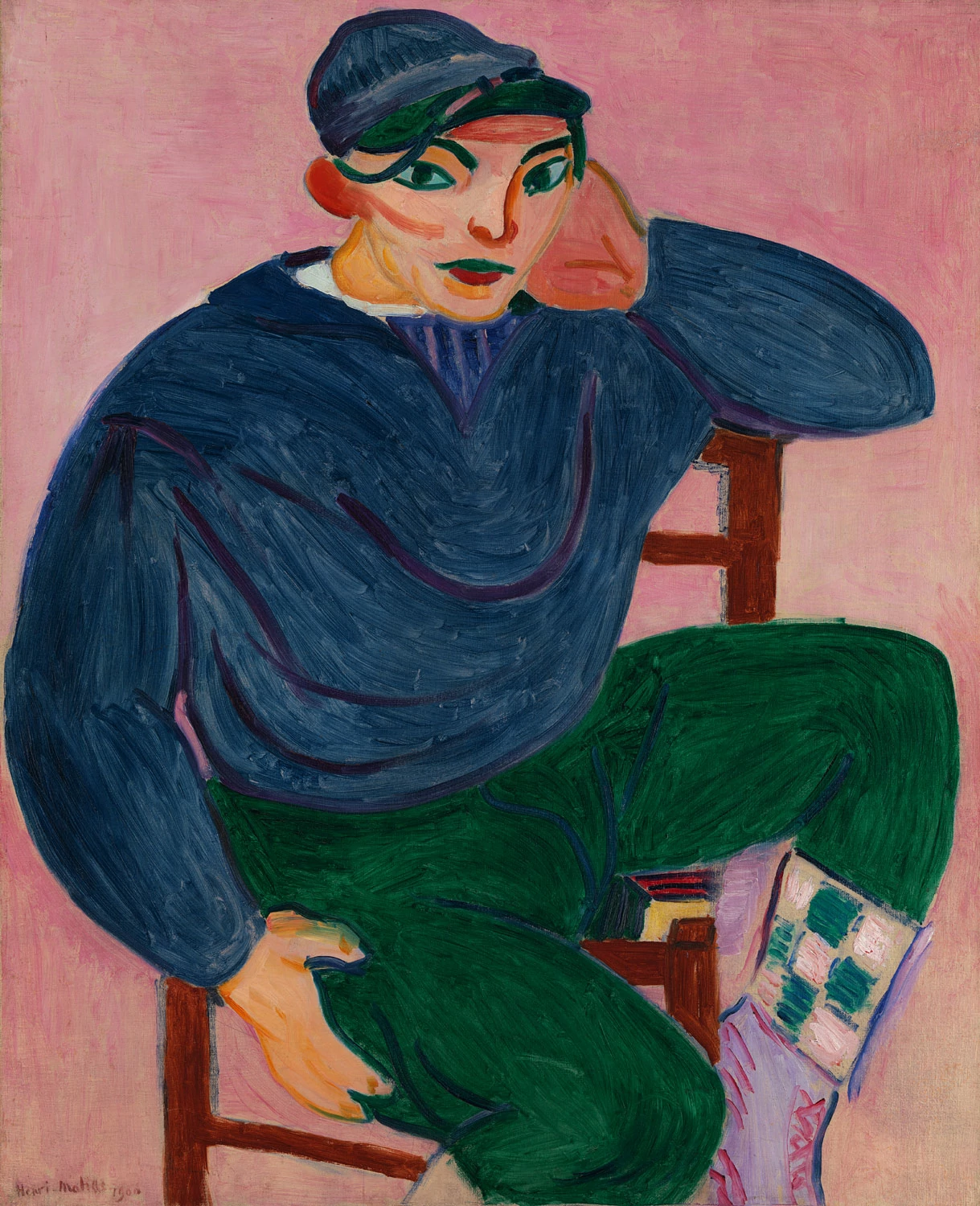

Let’s fast forward to 1905. Matisse has spent the last few years working in Paris alongside Georges Rouault, Andre Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Albert Marquet, Othon Friesz, Kees van Dongen, Jean Puy, Henri-Charles Manguin, Charles Camoin, and Louis Valtat, developing a radical new approach to painting, and it’s ready to be unveiled. The group carefully planned the unveiling, showing their work in the central room of the Salon d’Automne, a carefully curated art show more progressive then the academy but more rigorous than the pay-to-enter independent salon. When the show opened art critics were horrified.

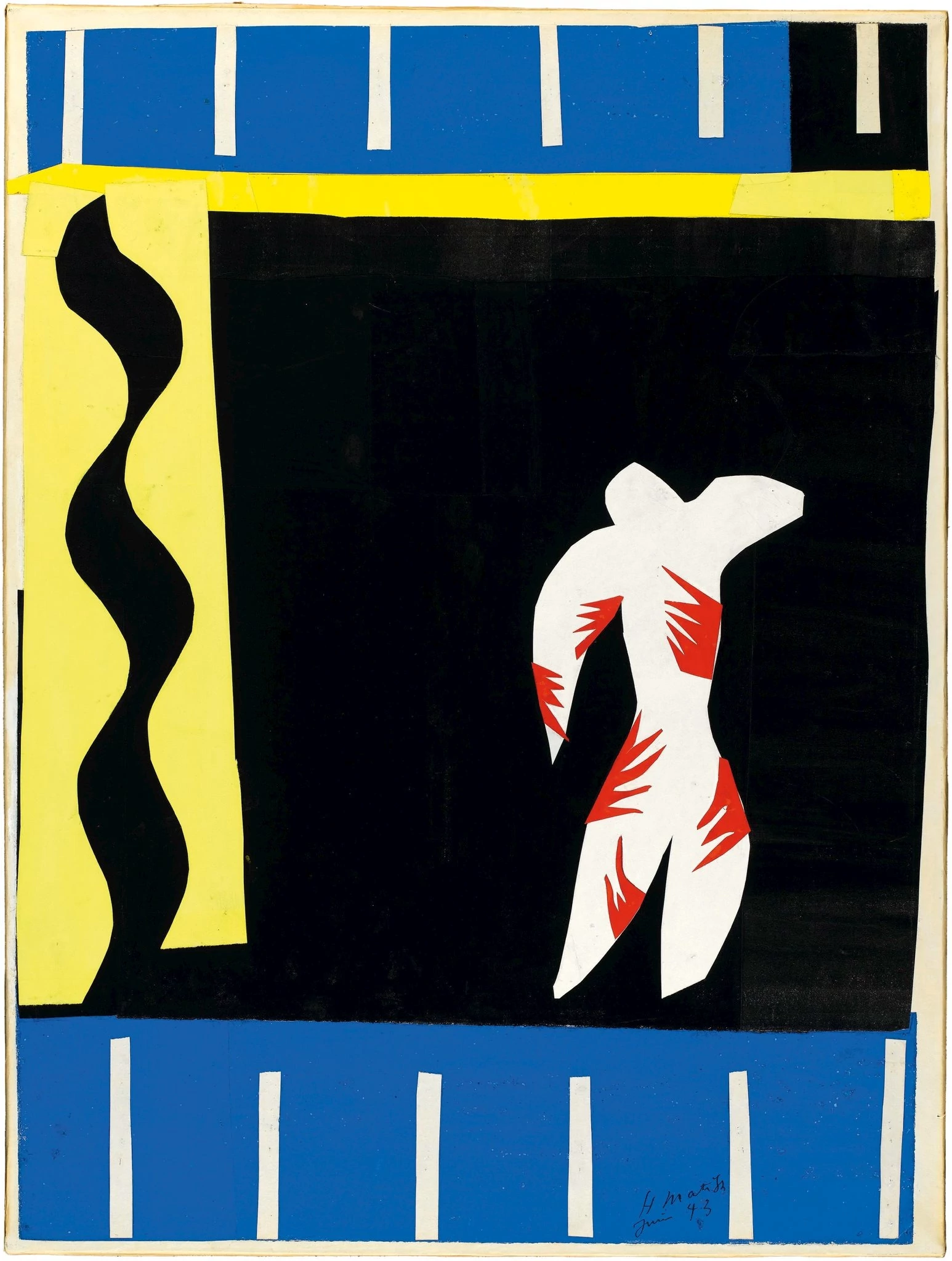

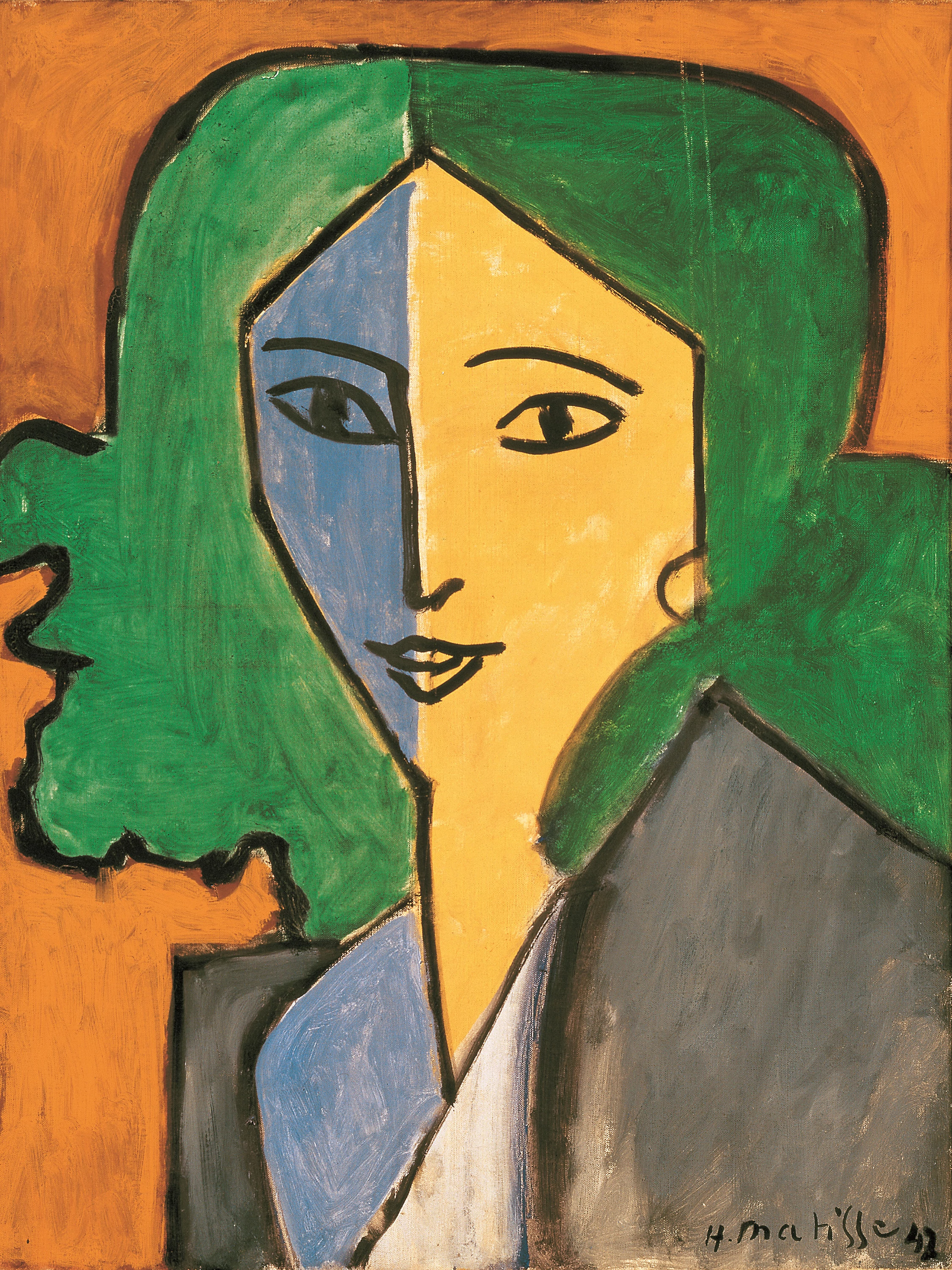

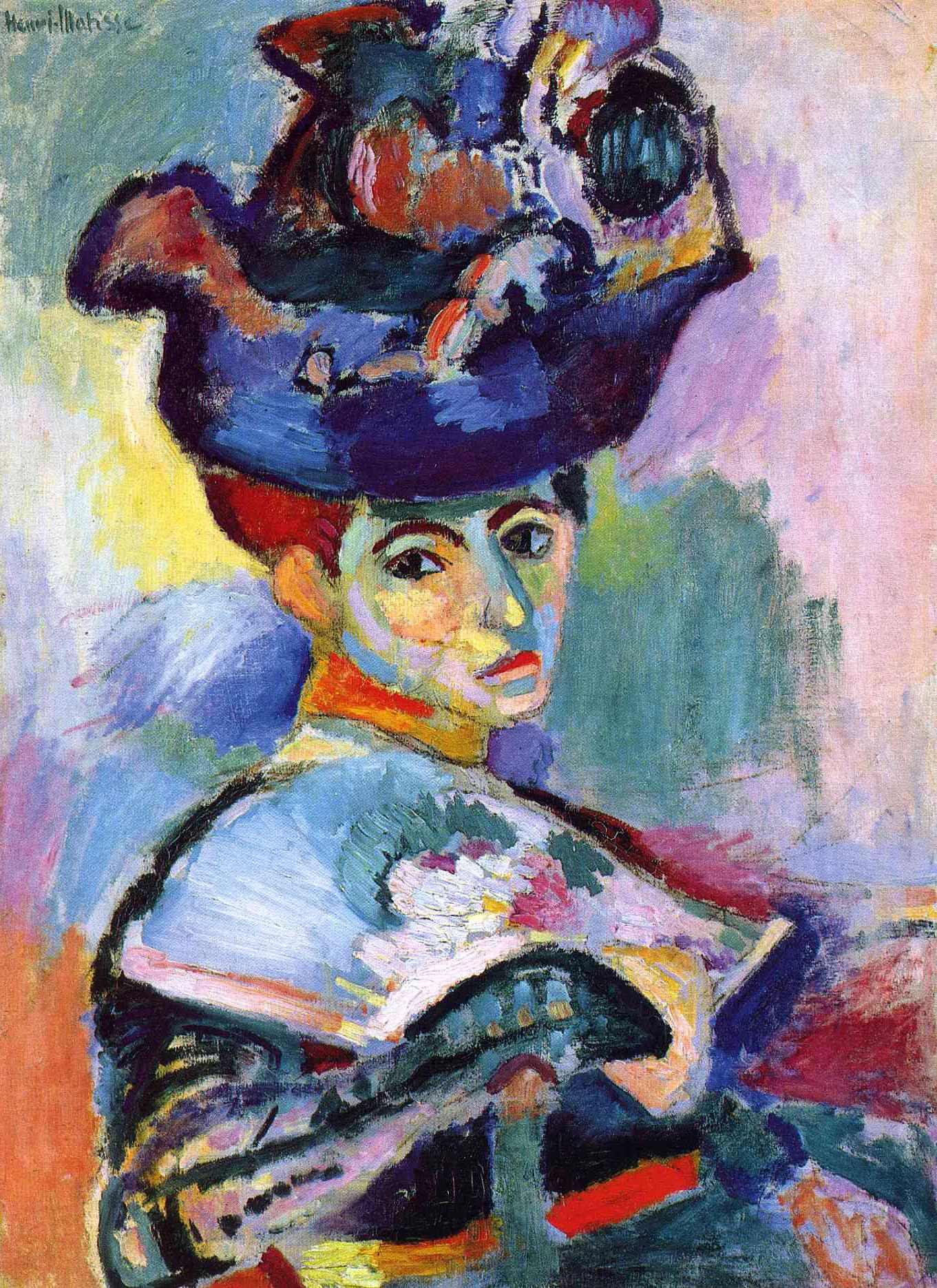

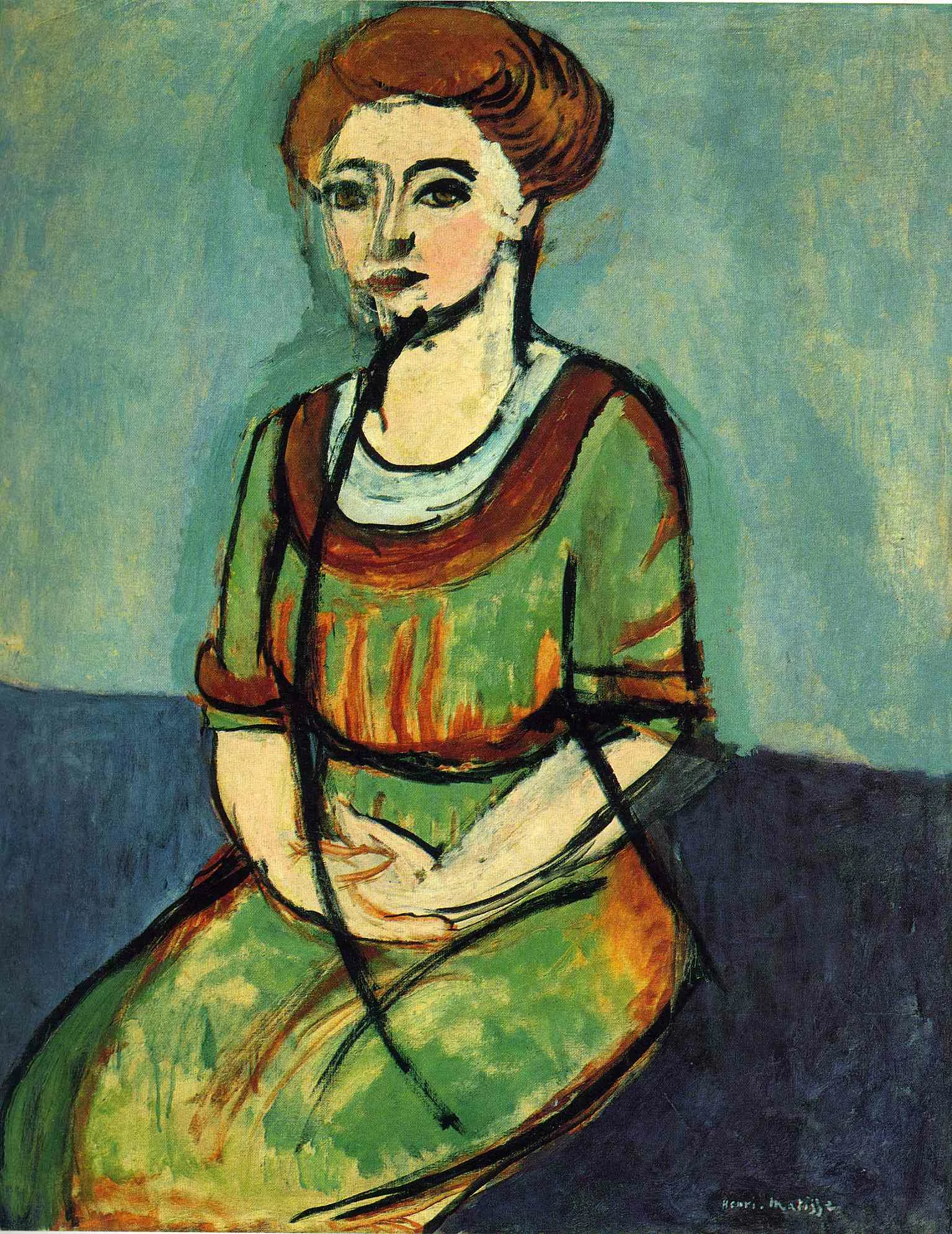

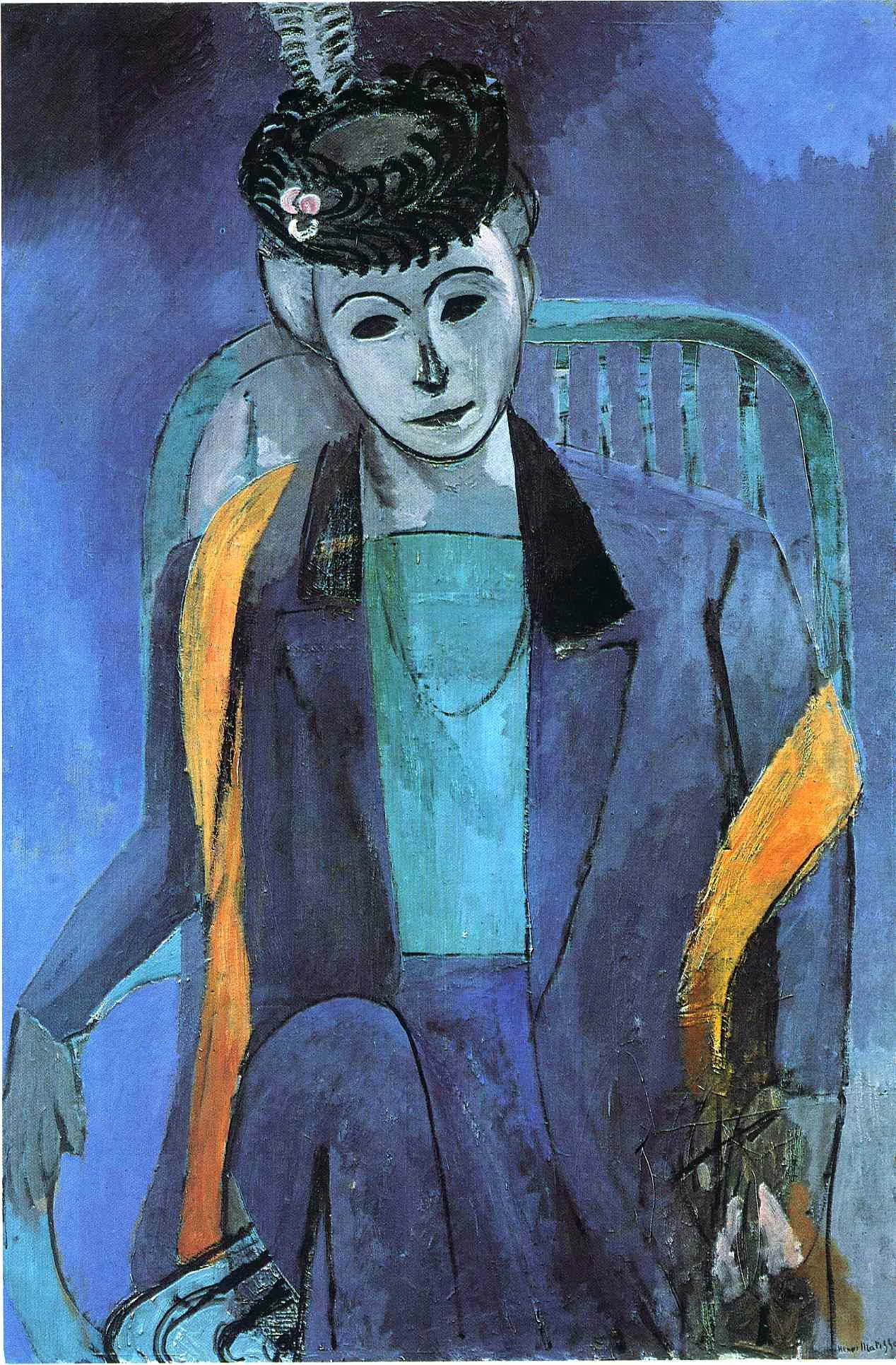

Explosive, unrestrained, violent color! Matisse and his friends had tossed out traditional approaches to realistic color, and building off the saturated dots of pigment in divisionist art, covered whole swaths of canvas with bright unmixed hues, sometimes straight from the tube. Exemplifying this reckless new approach to color was Matisse’s La Femme au chapeau, Woman with a Hat, a portrait of his wife Amelie Parayre. Today, it’s easy to appreciate the interesting color blocking and abstraction of hat and gown into pattern and suggestion, but in 1905, it quickly became gravity well for critical ire. “A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public” was the critic Camille Mauclair’s hand-wringing review, and contrasting a the work with a nearby neoclassical sculpture the art critic Louis Vauxcelles decried “Donatello au milieu des fauves!” Donatello among the wild beasts.

The wild beasts. You can’t buy a phrase that good, and it stuck. The new style pioneered by Matisse and co had a name, and with it, the credibility of an emerging movement. And invention is popular with investors. Dealers like Gertrude and Leo Stein began acquiring artworks in the new style, fueling the beginning of a decades-long color explosion that spanned Fauvism. Divisionism, Expressionism, and laid the foundation for countless contemporary movements.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Henri Matisse? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

Expression, for me, does not reside in passions glowing in a human face or manifested by violent movement. The entire arrangement of my picture is expressive.

My classical education naturally led me to study the Masters ... until the day when I realized that for me it was necessary to forget the technique of the Masters, or rather understand it in a completely personal manner. Isn’t this the rule with every artist of classical training?