There is power in autobiography. The ability to tell the story of your own life can be an opportunity to set the record straight, or edit the past. Few people create an autobiography that invents a new history from scratch, turning a violent, manic orphan onto an emperor and a saint.

Adolf Wölfli was a dangerous man, with an agonizingly tragic past. Adolf’s father left when he was five, and died a year later. Without the means to support her seven children, Adolf’s mother had him indentured to a local farmer, where he suffered abuse and continual overwork. In 1873, when Adolf was eight, his mother died, and without hope or family the boy sank into a childhood of slavery.

At 18, Wölfli left the farms of Zaziwil to go to Bern. He worked as a handyman, but lived in isolation and loneliness. Over the next decade, Wölfli’s behavior became aggressive, and instead of developing adult relationships, he began approaching young girls. He spent time in prison, and finally, after a third incident—an assault on a young child, Wölfli was committed to the Waldau Mental Asylum, where he lived the rest of his life.

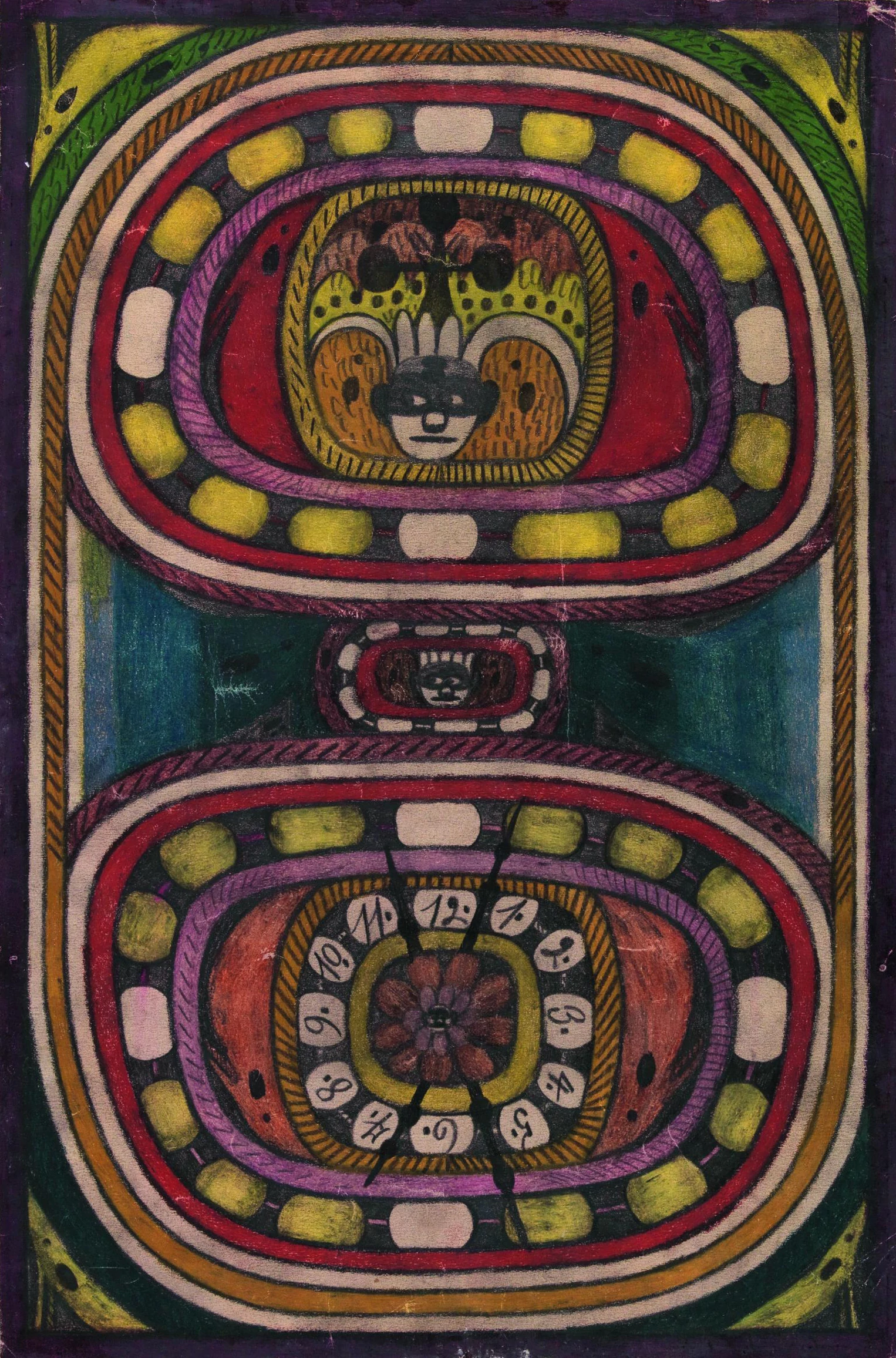

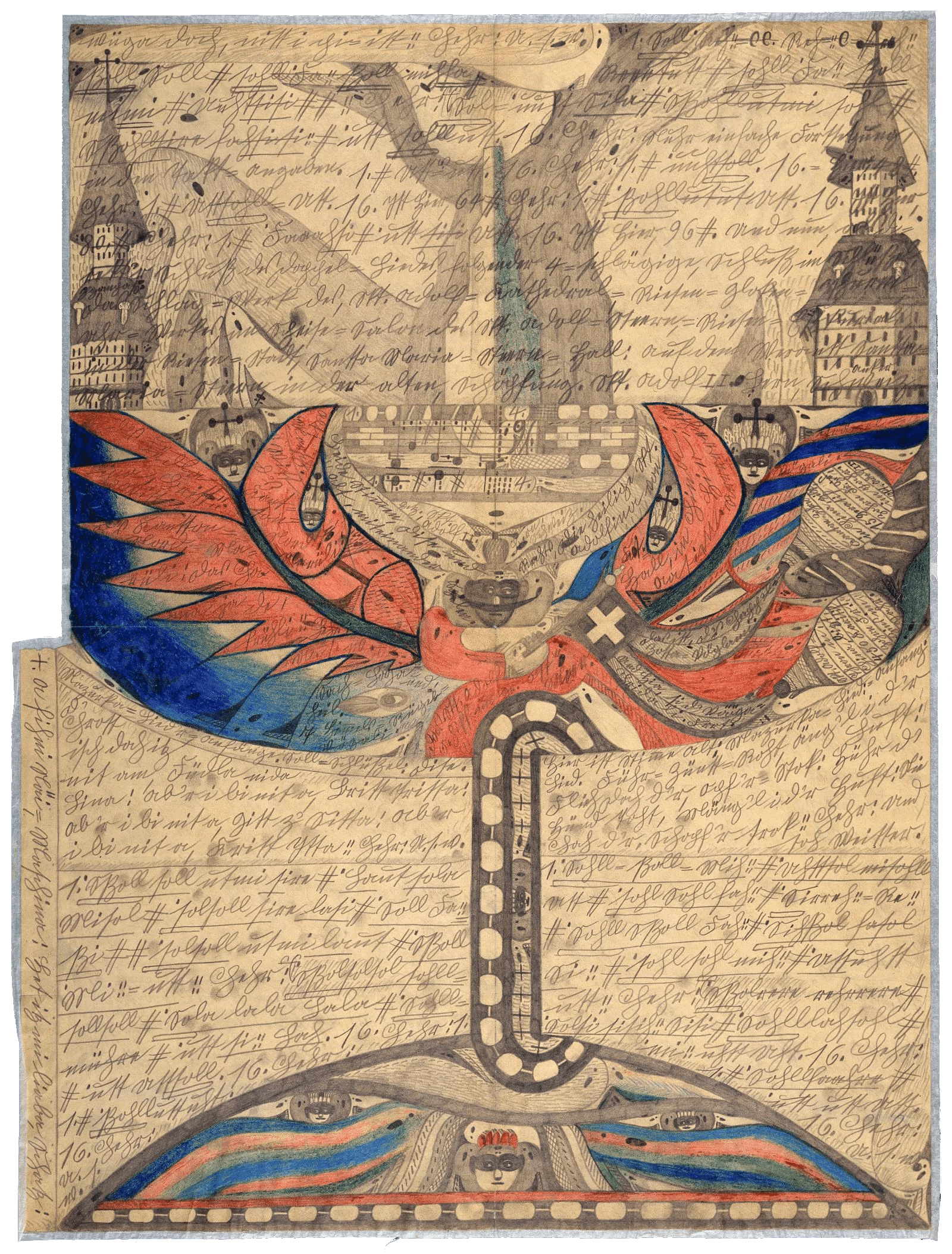

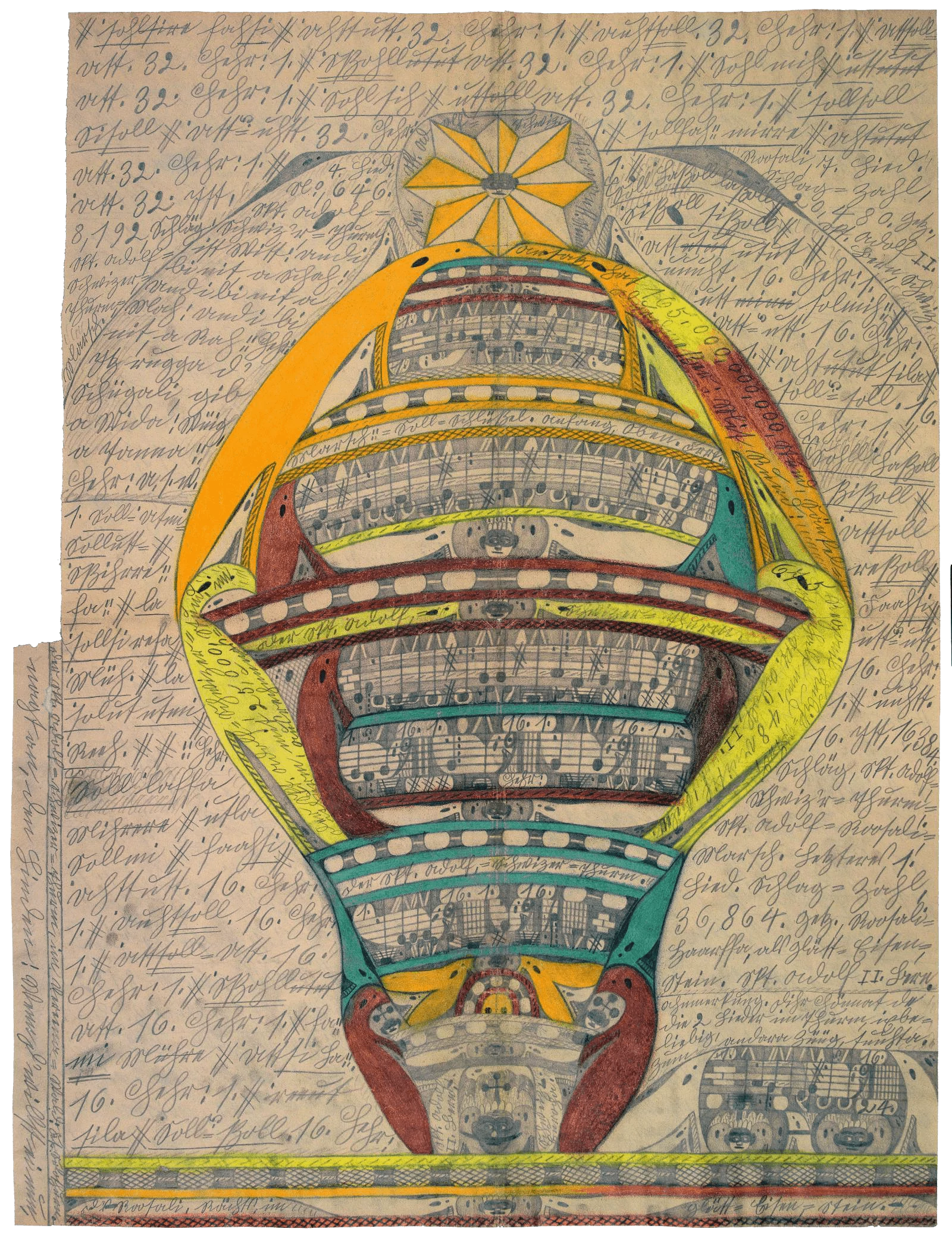

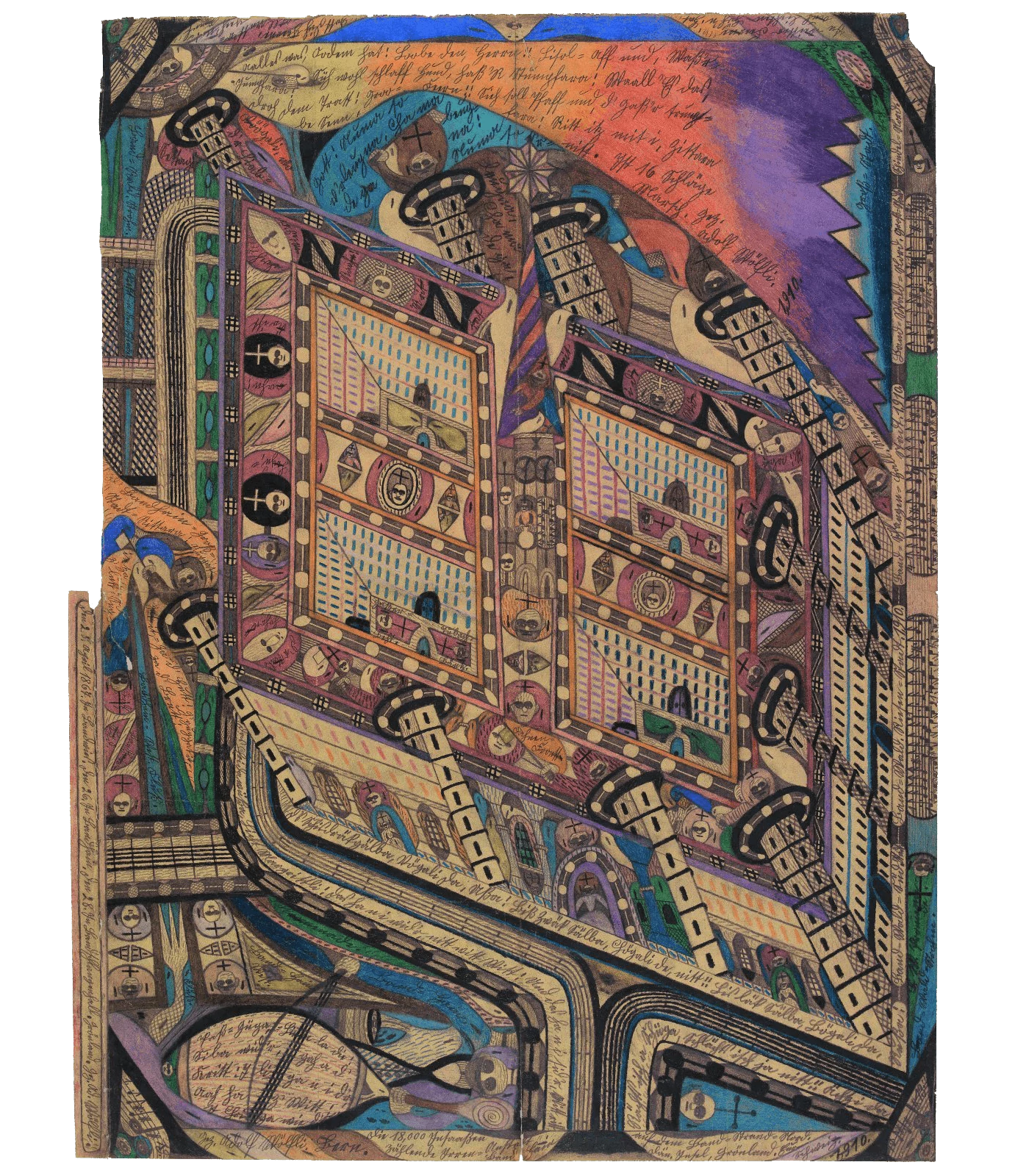

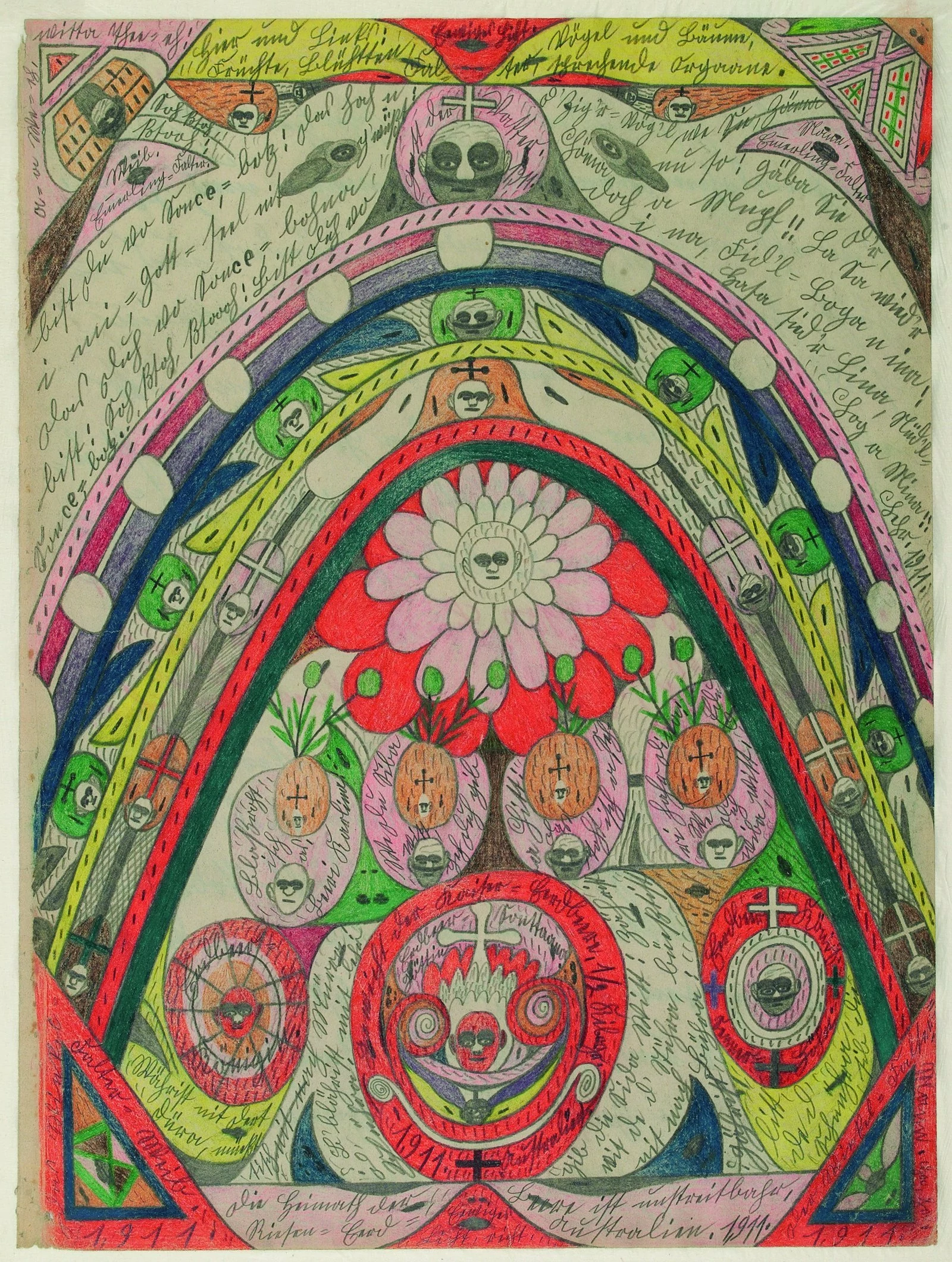

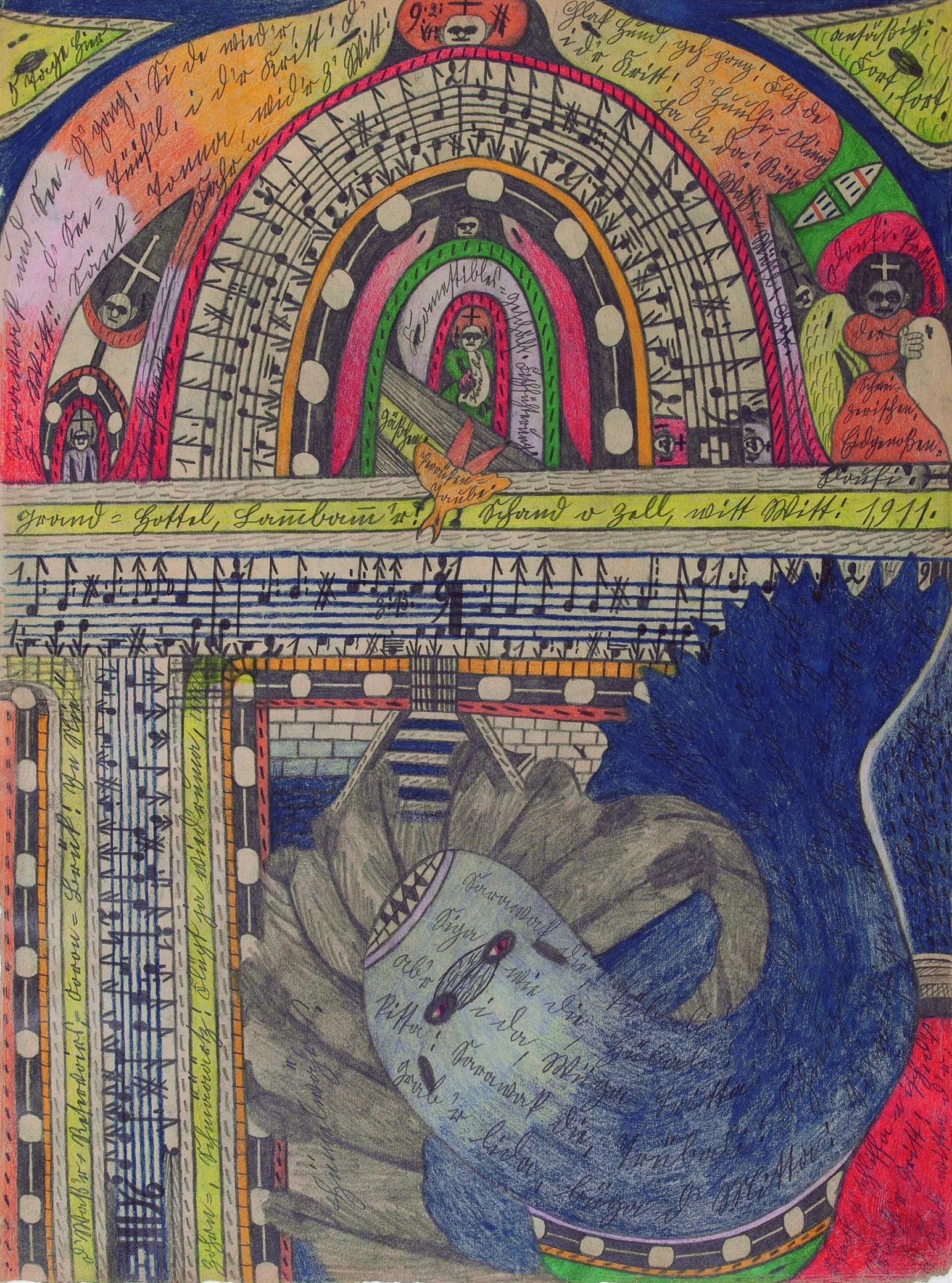

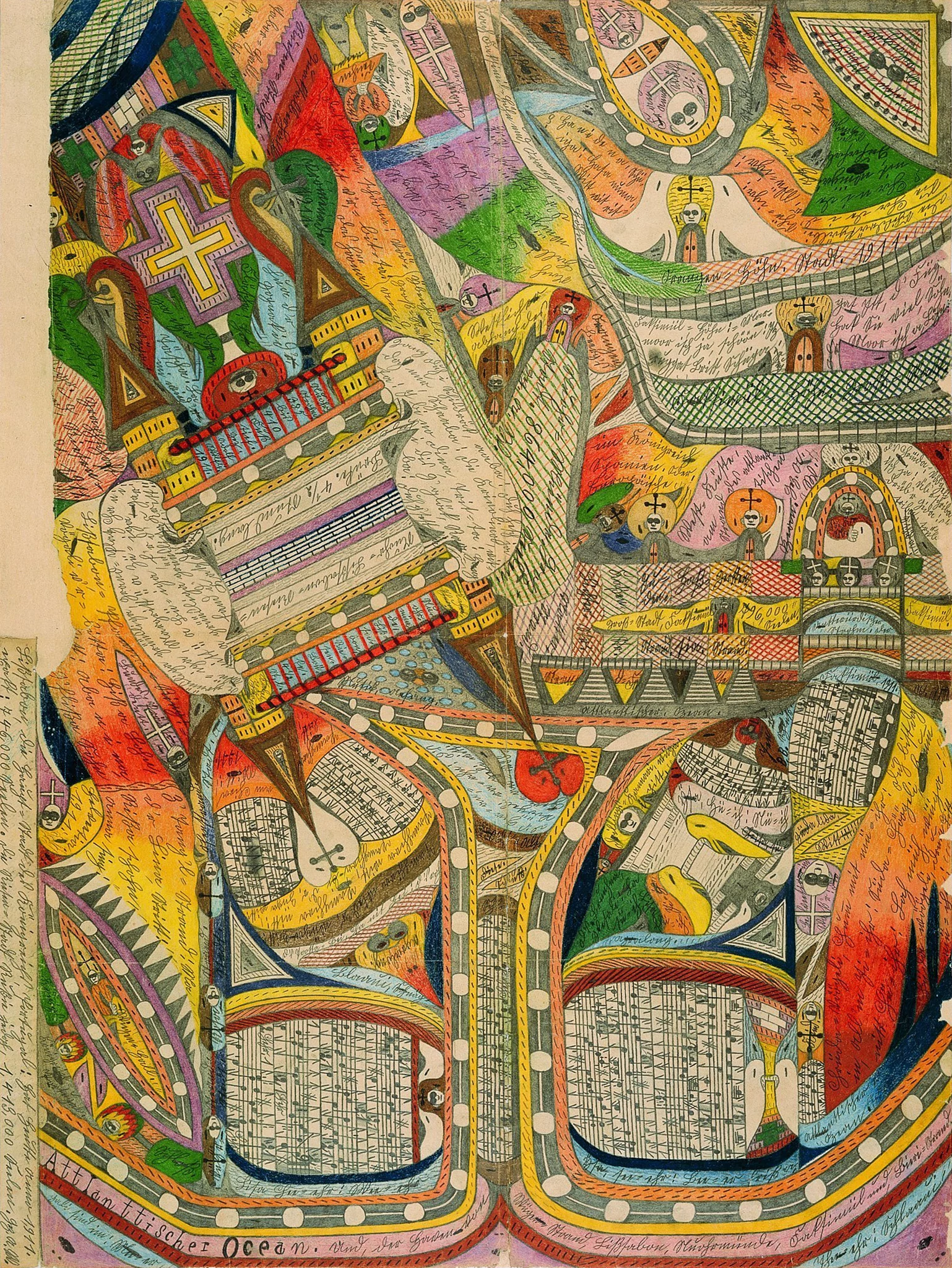

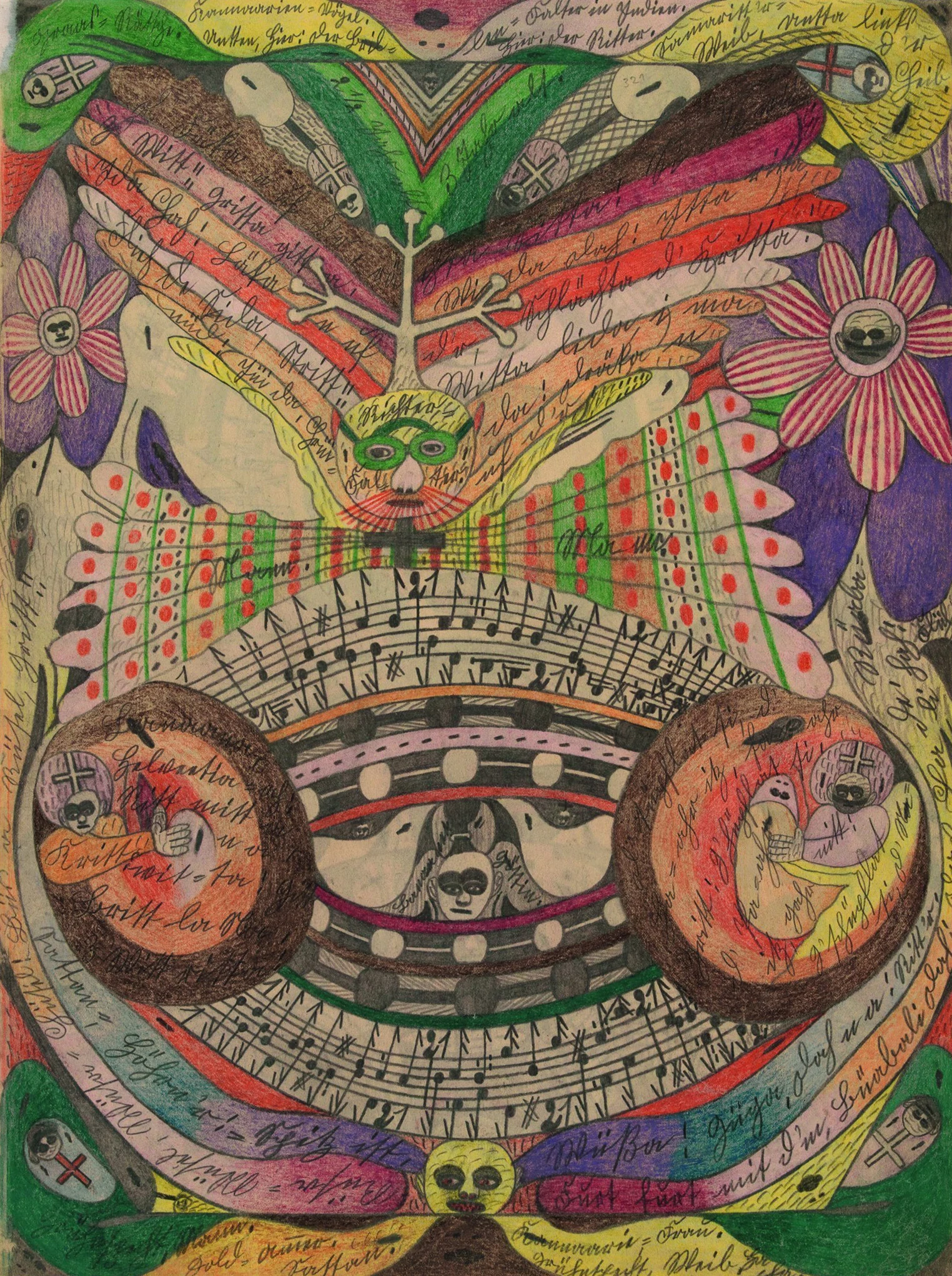

Wölfli was violent at first, breaking furniture and his cell door, but drawing calmed him, and he was given paper and pencils. This was the beginning of his autobiography. In 1908, Adolf Wölfli began his magnum opus, a utopian retelling of his life spanning 25,000 pages and thousands of illustrations, maps and invented musical scores. “From the Cradle to the Grave” - the first volume, tells the story of his childhood, not as an enslaved orphan, but as a world traveler, an adventurer who catalogued talking plants and met with foreign kings. The next four volumes documented an even greater change: the child-traveler Wölfli having attained all earthly wisdom, evolving into a cosmological, metaphysical structure called the “Saint Adolf-Giant-Creation” a force of order that brings structure to the entire universe.

The intense, inventive work of Adolf Wölfli was documented in 1921 by Walter Morgenthaler, a doctor at Waldau, in a paper titled Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler “A Psychiatric Patient as Artist.” This was the art world’s introduction to Wölfli, and while in his lifetime he traded his drawings to visitors for colored pencils, his work was rediscovered by Jean Dubuffet around 1950, and included in the growing Art Brut movement. Wölfli’s art has been played by musicians, studied by psychologists, and became one of the first examples of Outsider Art. But these are more than drawings—they’re a new world, created to replace the pain and tragedy of life with adventure, and transform their artist from an orphan into a god-king.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Adolf Wölfli? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

Sit today, my dear child: whosoever's hungry, may bark: the warhose flies in the wind: the pointer with the trowel: is truly my worst foe.