Islamic Dynastic Art

When you don't paint people, things get beautifully, powerfully decorative.

In 609 CE, Muhammad received a vision from the angel Gabriel—the first of many. These messages were compiled into a holy book, the Quran, and became the foundation of Islam, the world’s third major monotheistic religion. Muhammad is considered a prophet, but he was also a brilliant politician. In the 7th century CE, the people of the Arabian peninsula were fragmented, Jewish and Quraysh tribes navigated a semi-peaceable anarchy on the fringes of a massive conflict between the Sasanian and to the north. From his homebase in Medina, Muhammad wrote a charter that brokered peace between the region’s disparate tribes and religions, and unified them in war.

And war came quickly. The decades-long conflict between the Sasanian and Byzantine Empires had left their economies shallow and their people overtaxed. After Muhammad’s death in 632, four Caliphs, Islamic leaders, led a series of campaigns into Byzantine territory, and in 30 years conquered Persia, North Africa, Egypt and much of the Eastern Mediterranean. The secret to their speed was the culture they offered. The Caliphs instituted welfare for widows, orphans and the elderly, and taxed Jews and Christians less than the Byzantines had. The Islamic Empire was born, and people were excited.

So now we can talk about Islamic art, a unique and amazingly consistent set of styles that have lasted from the 7th century to the modern era. You’ll notice one thing about Islamic art right out of the gate—no people. This is called aniconism, and it’s the “absence of material representations of the natural and supernatural world in various cultures.” In Islam, the Quran cautions against the creation of idols, lest humanity begin worshipping their own creations in place of God. This manifested itself as an absolute prohibition against depicting God, Muhammad or other prophets, and a general avoidance of pictorial representation in the broader culture, which continued until the advent of the camera. While much Western art of the time was devoted to pictorial representations of God and saints, aniconism has appeared in other cultures, including early Buddhist art and in Christian art during the Protestant Reformation.

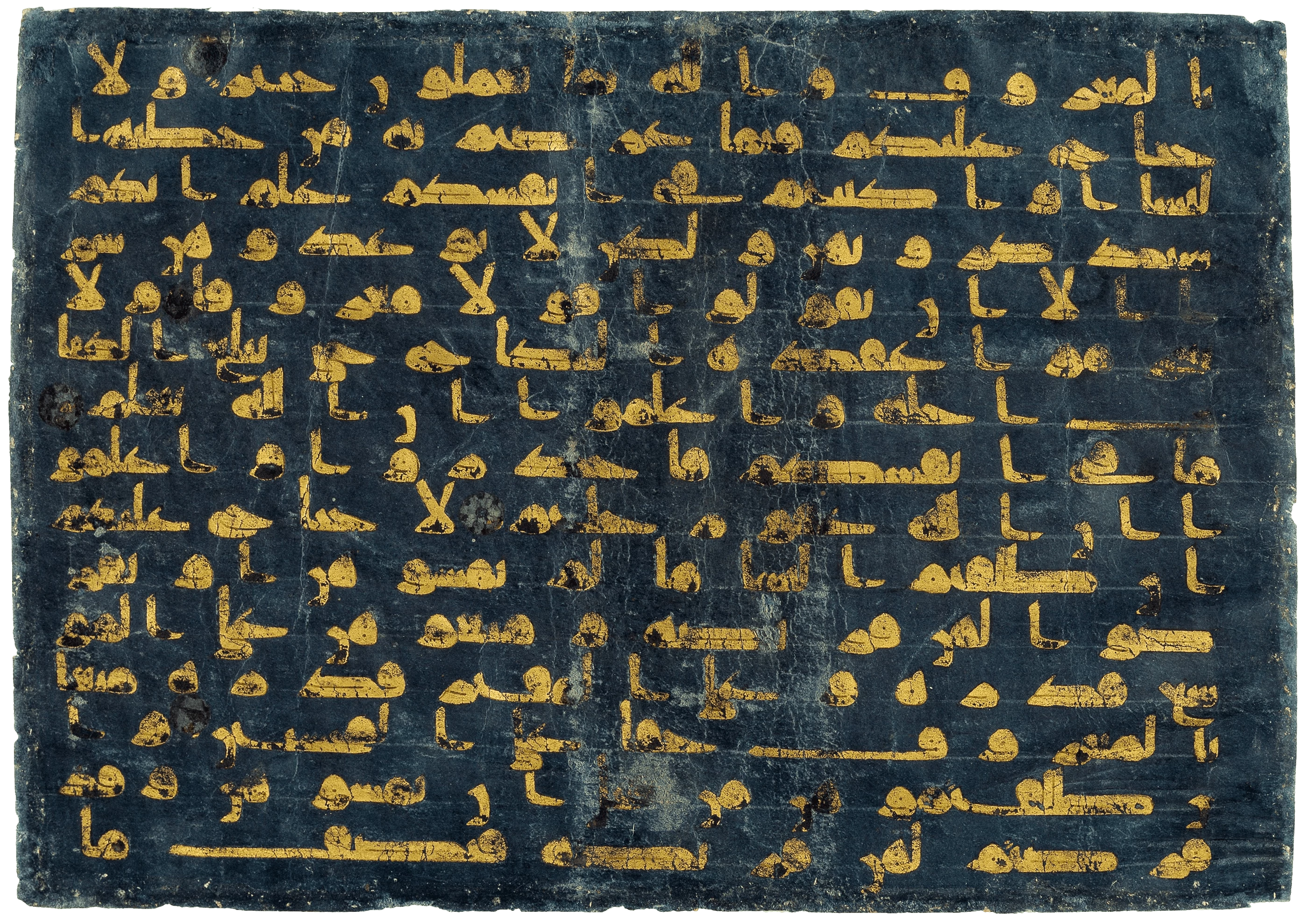

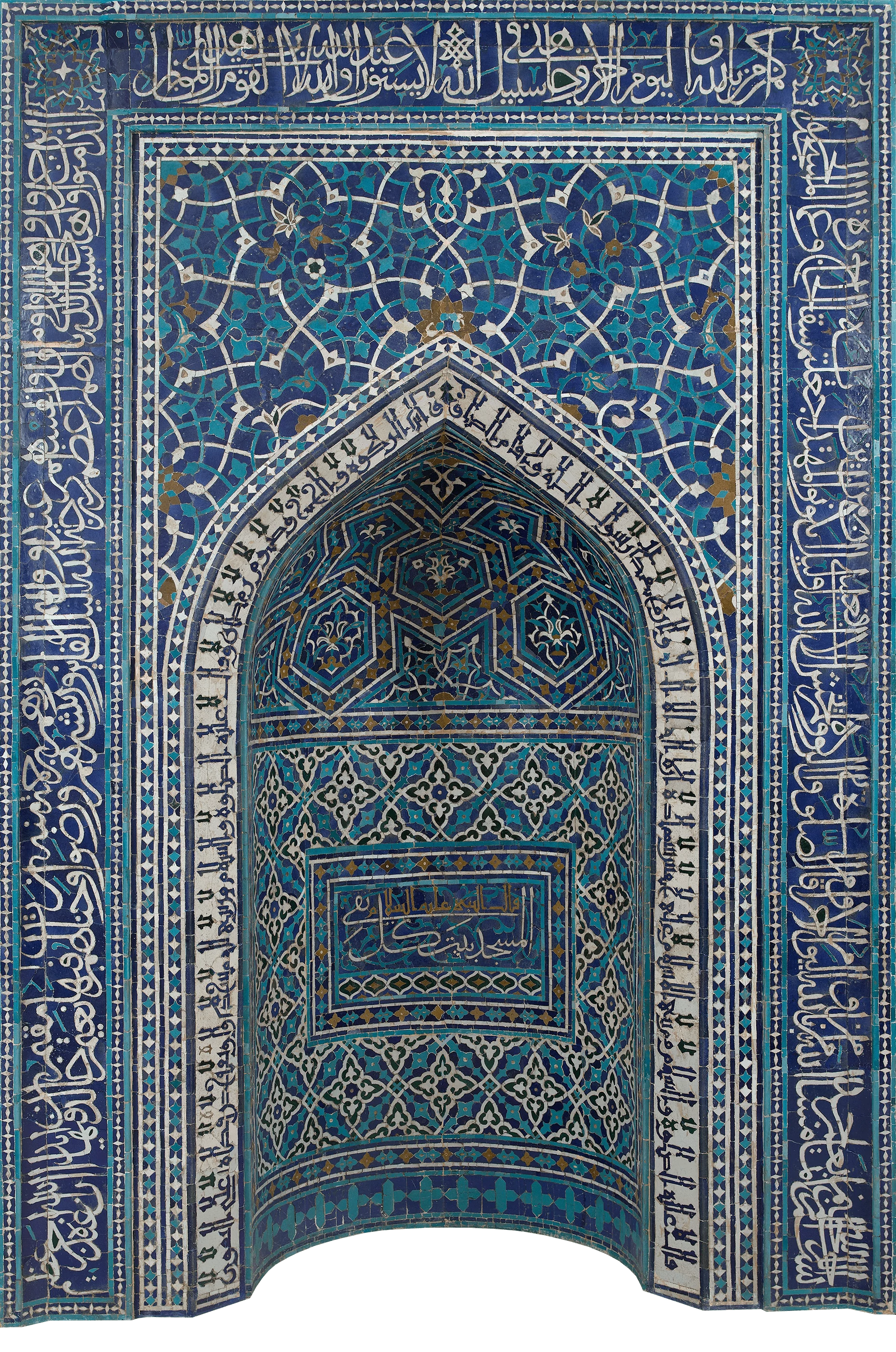

Without the human form, Islamic art evolved three refined, beautifully distinctive styles of decorative art: calligraphy, geometric patterning, and vegetal arabesque.

While most cultures with written language develop a calligraphic practice, the Arabic script may use both vertical and horizontal space to bring drama to the inscription. The earliest script, a bold and powerful style called Kufic, was used from the 7th to the 10th century, and has a similar feel to European blackletter. The later style, Naskh, was invented around 900 CE and was lighter and smoother, designed for faster copying. Geometric patterns are also found in many cultures, but rarely are they explored to such depth as in Islamic art. Applied to furniture, pottery, architectural surfaces and flat design, Islamic patterning uses a few simple forms, circles and interlaced circles, squares and the ever-present star to combine into infinitely complexity and variation. Vegetal patterns bring the curves of a lush garden to Islamic art. Flower petals, leaves, and twisting vines are often used to complement geometric patterns. Individually, these elements were applied to nearly every possible surface: pottery, jewelry, furniture, clothing, and rugs, and brought beauty into the home, the church and to public spaces. But the full power of Islamic art appears when these elements are combined. Often set into shallow relief tiles and applied inside and out to architecture, as on the Dome of the Rock, the detail and density of calligraphy, geometry and vegetal patterns combined creates a totally overwhelming physical presence.

Islamic art as a style doesn’t end, but it does change. From 1300 onward, the Islamic world began to split into three distinct empires: the Turkish Ottoman Empire, the Indian Mughal Empire, and the Iranian Safavids, each with their own distinct evolutions of the gloriously detailed decorative styles of Islamic art.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Islamic Dynastic Art? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.

Every one shall have his portion from the side to which he belongs.

Have I given the message?—O Allah, be my witness.