Impressionism

Light and movement as the crux of human perception

1860 – 1900And so they run on, those endless galleries of high and low life, branching off at intervals into innumerable tributaries and backwaters. For the few minutes that remain, let us leave them for a world which, if not exactly pure, is at any rate more refined; a world where we shall breathe perfumes not perhaps more healthful, but at least more delicate. I have already remarked that the brush of Monsieur G., like that of Eugene Lami, is marvelously skilled at portraying the rites of dandyism and the elegance of foppery. The physical attitudes of the rich are familiar to him; with a heft-stroke of the pen and a sureness of touch which never deserts him, he is able to give us that assurance of glance, gesture and pose which is a result of a life of monotony in good fortune. In the particular series of drawings of which I am thinking we are shown a thousand aspects and episodes of the outdoor life—racing, hunting, drives in the woods, proud ‘ladies’ and frail ‘misses’ expertly controlling their exquisitely graceful steeds, themselves no less dazzling and dainty thin their mistress, For Monsieur G. is not only a connoisseur of horses in general, but has also a happy gift for expressing the personal beauty of the individual horse. At one moment it is wayside halts, bivouacs, as it were, of innumerable carriages, from which slim young men and women garbed in the eccentric costumes authorized by the season, hoisted up on cushions, on seats, or on the roof, are assisting at some ceremony of the turf which is going on in the distance; at another, a rider is seen galloping gracefully alongside an open barouche, and even his horse seems, by his prancing curtseys, to be paying his respects in his own way. The carriage drives off at a brisk trot along a pathway zebra'd with light and shade, carrying its freight of beauties couched as though in a gondola, lying back idly, only half listening to the gallantries which are being whispered in their ears, and lazily giving themselves up to the gentle breeze of the drive.

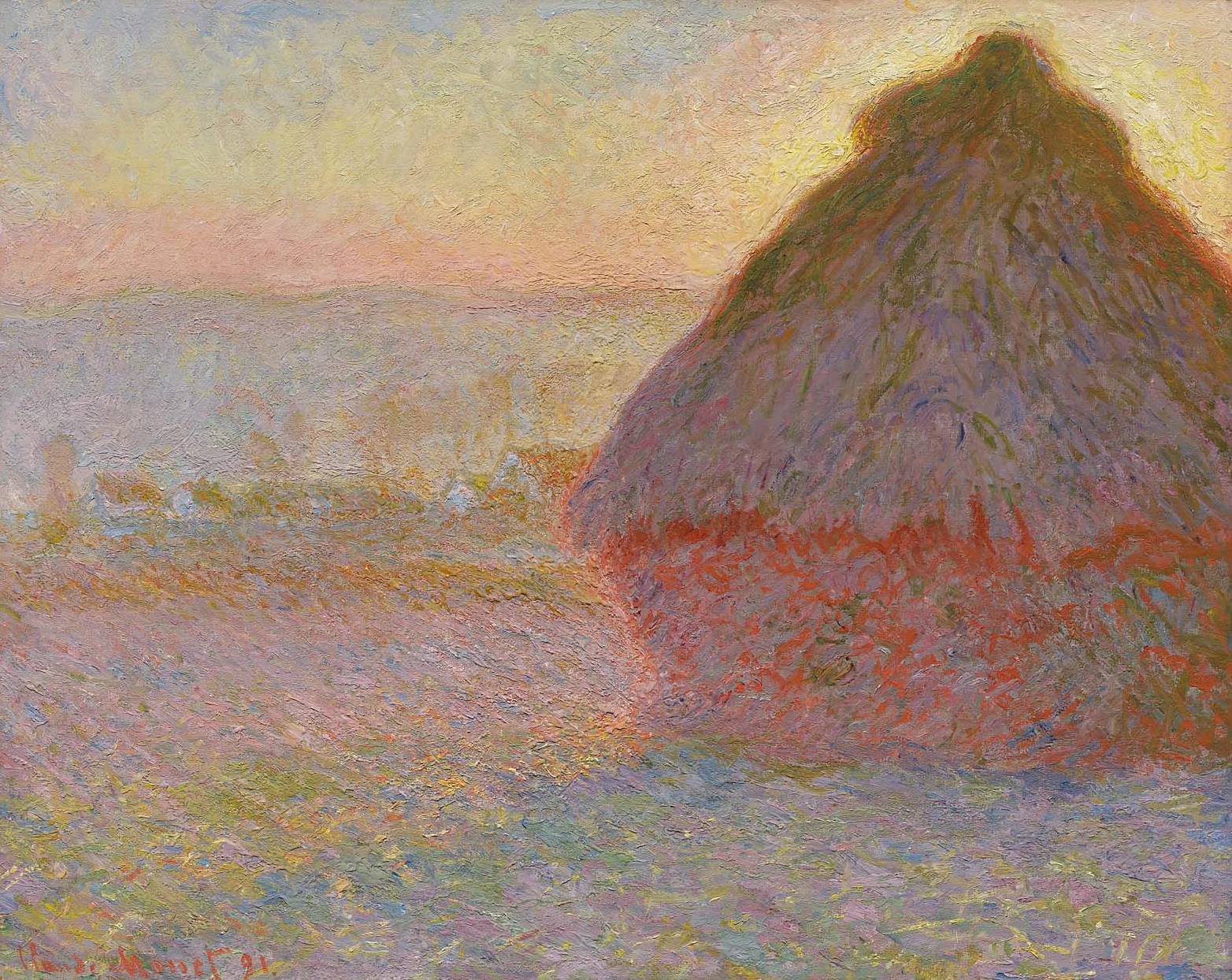

Fur or muslin lap around their chins, billowing in waves over the carriage-doors. Their servants are stiff and erect, motionless and all alike. It is always the same monotonous and self-effacing image of servility, punctual and disciplined; its distinctive quality is to have none. The woods in the background are green or russet, dusty or gloomy, depending upon the time of day and the season. Their glades are tilled with autumnal mists, blue shadows, golden shafts of light, effulgences of pink, or sudden flashes which cut across the darkness like rapier-thrusts.

If Monsieur G.’s powers as a landscape-painter had not already been revealed to us in his countless watercolors dealing with the Eastern War, these would most certainly be enough to do so. Here however we are no longer concerned with the butchered countryside of the Crimea or the operatic is of the Bosphorus; instead We are back in those intimate, familiar landscapes which fringe the skins of a great city, where the light creates effects which no truly Romantic artist could disregard.

Another merit which deserves to be noticed at this point is our artist’s remarkable understanding of harness and coachwork. He draws and paints each and every kind of carriage with the same care and ease as an expert marine-painter all sorts of ships. His coachwork is always consummately accurate; each detail is in its place, and no fault can be found with it. In whatever attitude it may be caught, at whatever speed it may be running, a carriage, like a ship, derives from its movement a mysterious and complex grace which is very difficult to note down in shorthand. The pleasure which it affords the artist’s eye would seem to spring from the series of geometrical shapes which this object, already so intricate, whether it be ship or carriage, cuts swiftly and successively in space.

I am convinced that in a few years’ time Monsieur G.’s drawings will have taken their place as precious archives of civilized life. His works will be sought after by collectors as much as those of the Debucourts, the Moreaus,’ the Saint-Aubins, the Carle Vernets, the Deverias, the Gavarnis, and all than other delightful artists who, though depicting nothing but the familiar and the charming, arc in their own way no less of serious historians. A few of them have even sacrificed too much to charm, and have sometimes introduced into their compositions a classic style alien to the subject; some have deliberately rounded their angles, smoothed the rough edges of life and toned down its dashing highlights. Less skillful than they, Monsieur G. retains a remarkable excellence which is all his own; he has deliberately fulfilled a function which other artists have scorned and which it needed above all a man of the world to fulfill. He has everywhere sought after the fugitive, fleeting beauty of present-day life, the distinguishing character of that quality which, Ito* the reader’s kind permission, we have called ‘modernity'. Often weird, violent and excessive, he has contrived to concentrate in his drawings the acrid or heady bouquet of the wine of life.