Zaire School of Popular Painting

Art as history, protest and education in the DRC

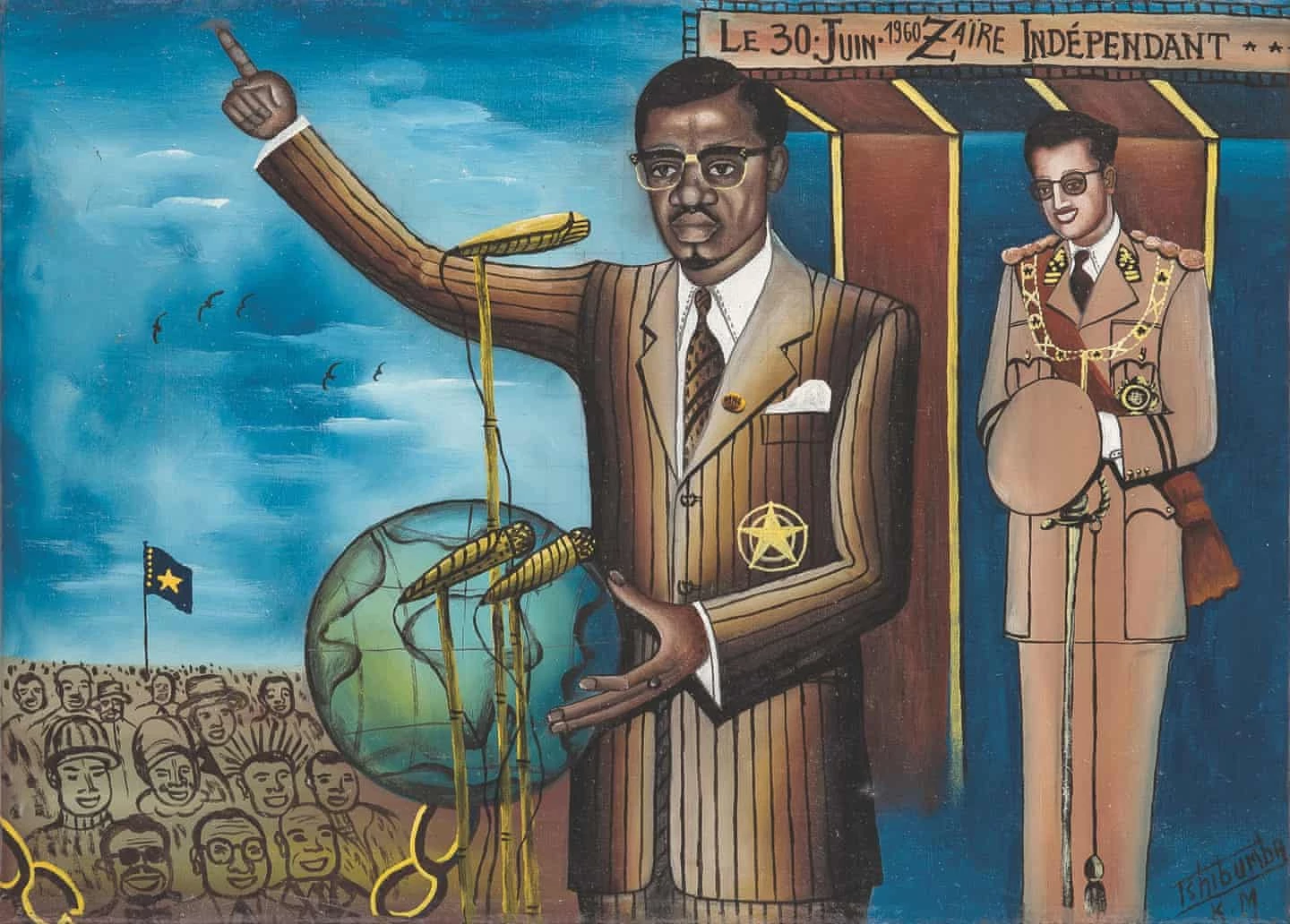

In the late 1950s a wave of independence swept through Africa. A continent that had been divided up and exploited by European imperialists for nearly 80 years was winning itself back. Decolonization took two decades and required courageous political leadership, public outcry, riots and in some cases, guerrilla-style warfare. The independent countries that emerged needed a voice to process their pain, their strength, and their hope. In the newly created Democratic Republic of the Congo, called the Republic of Zaire until 1997, that took the form of the Zaire School of Popular Painting.

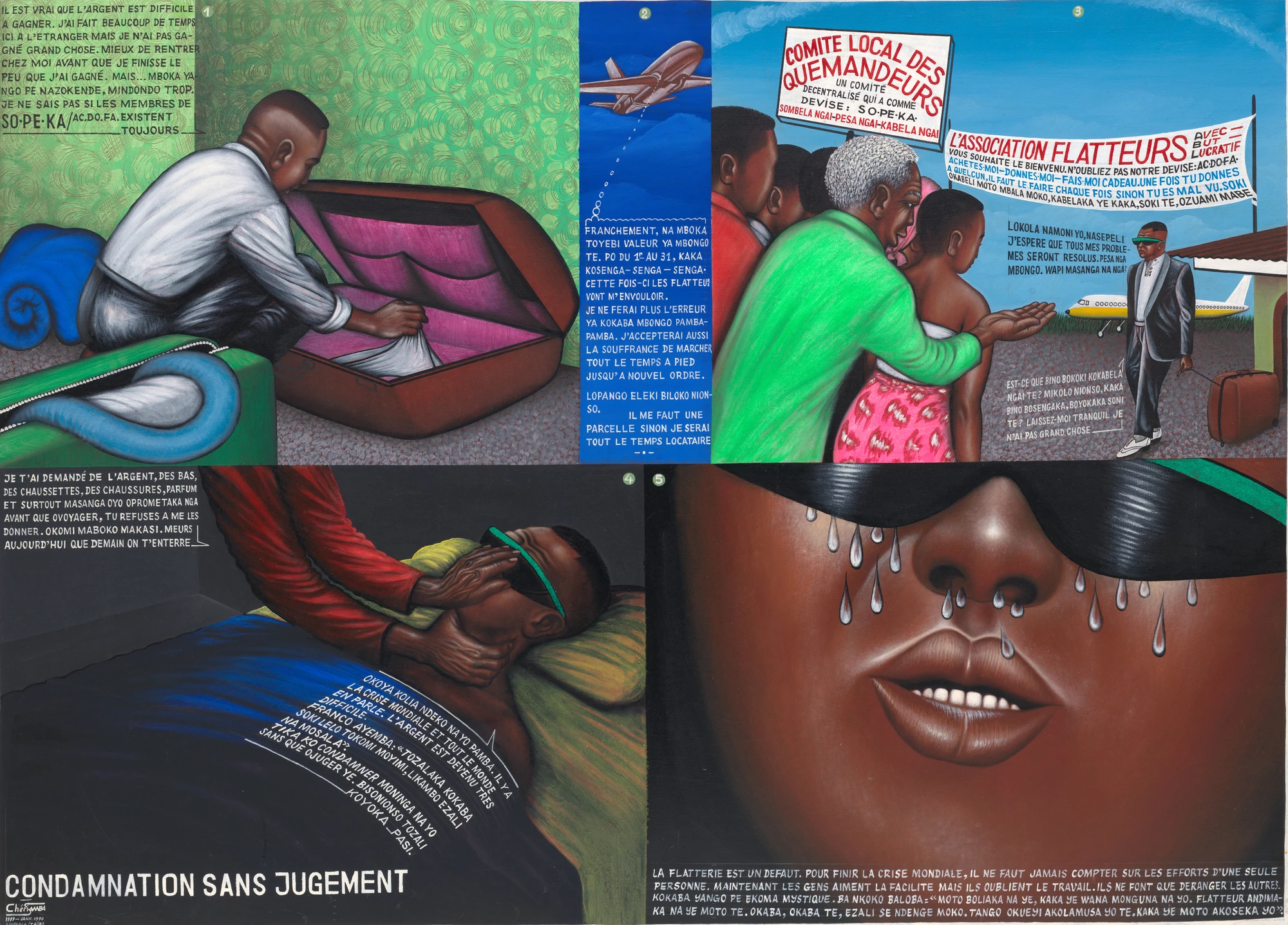

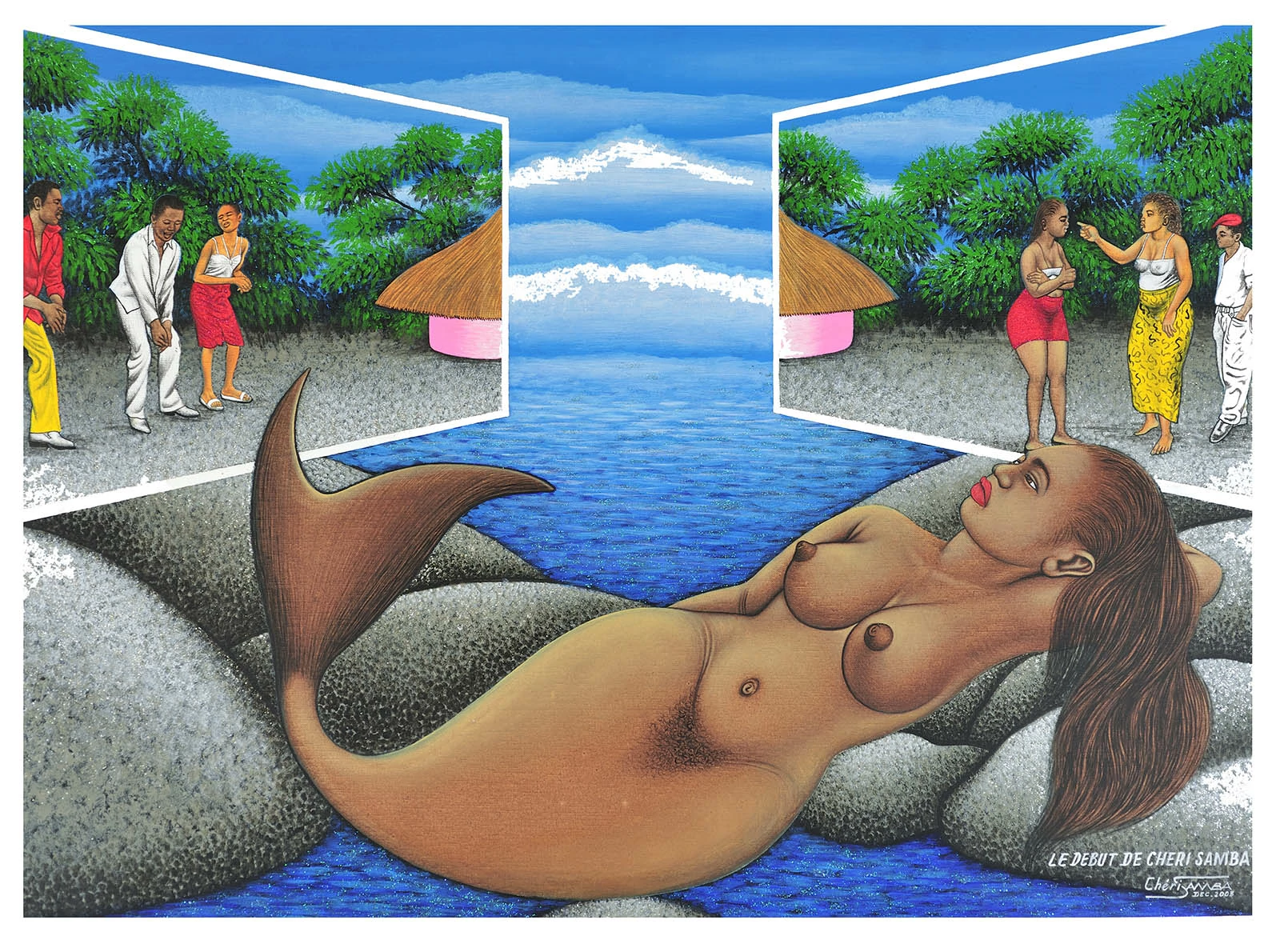

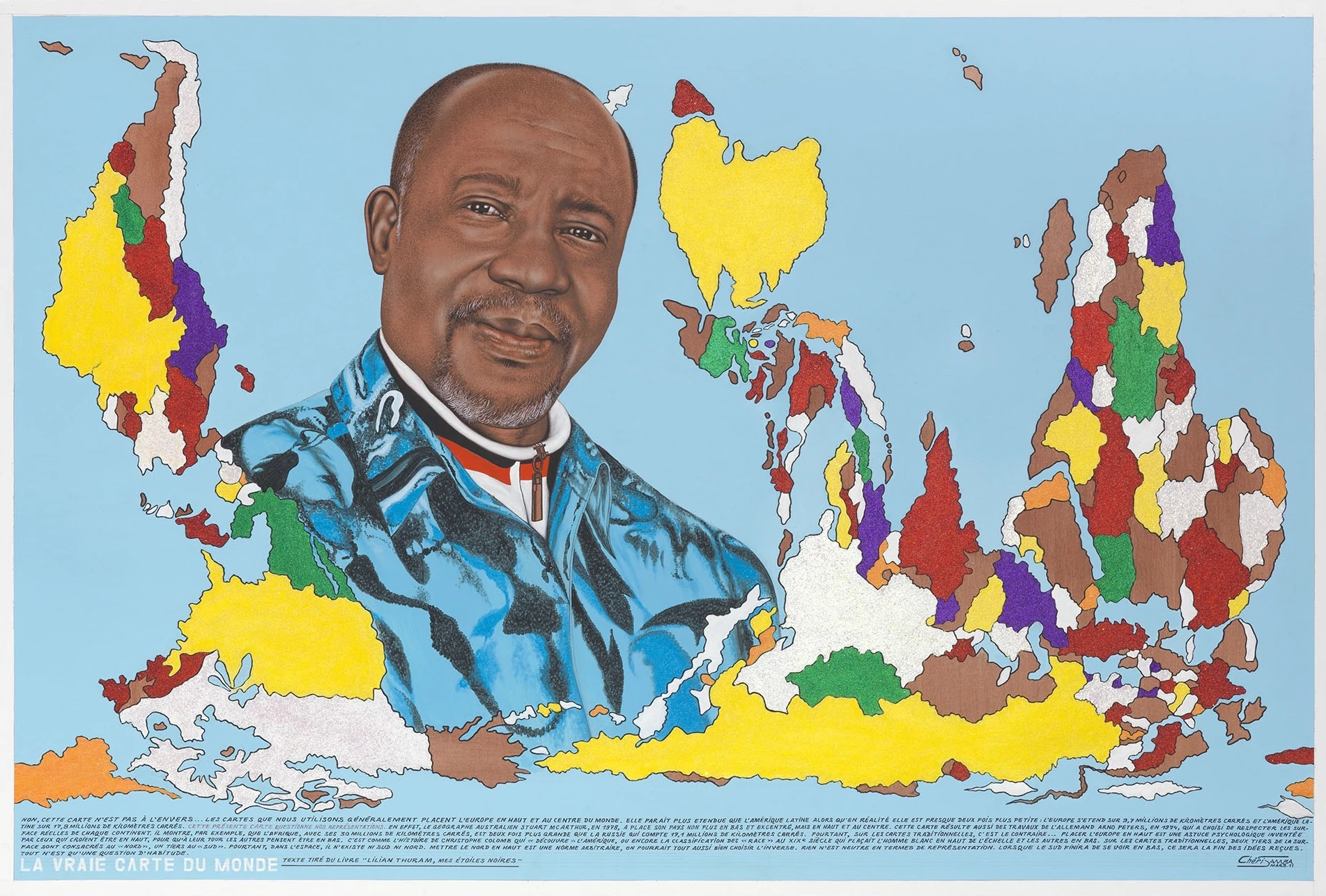

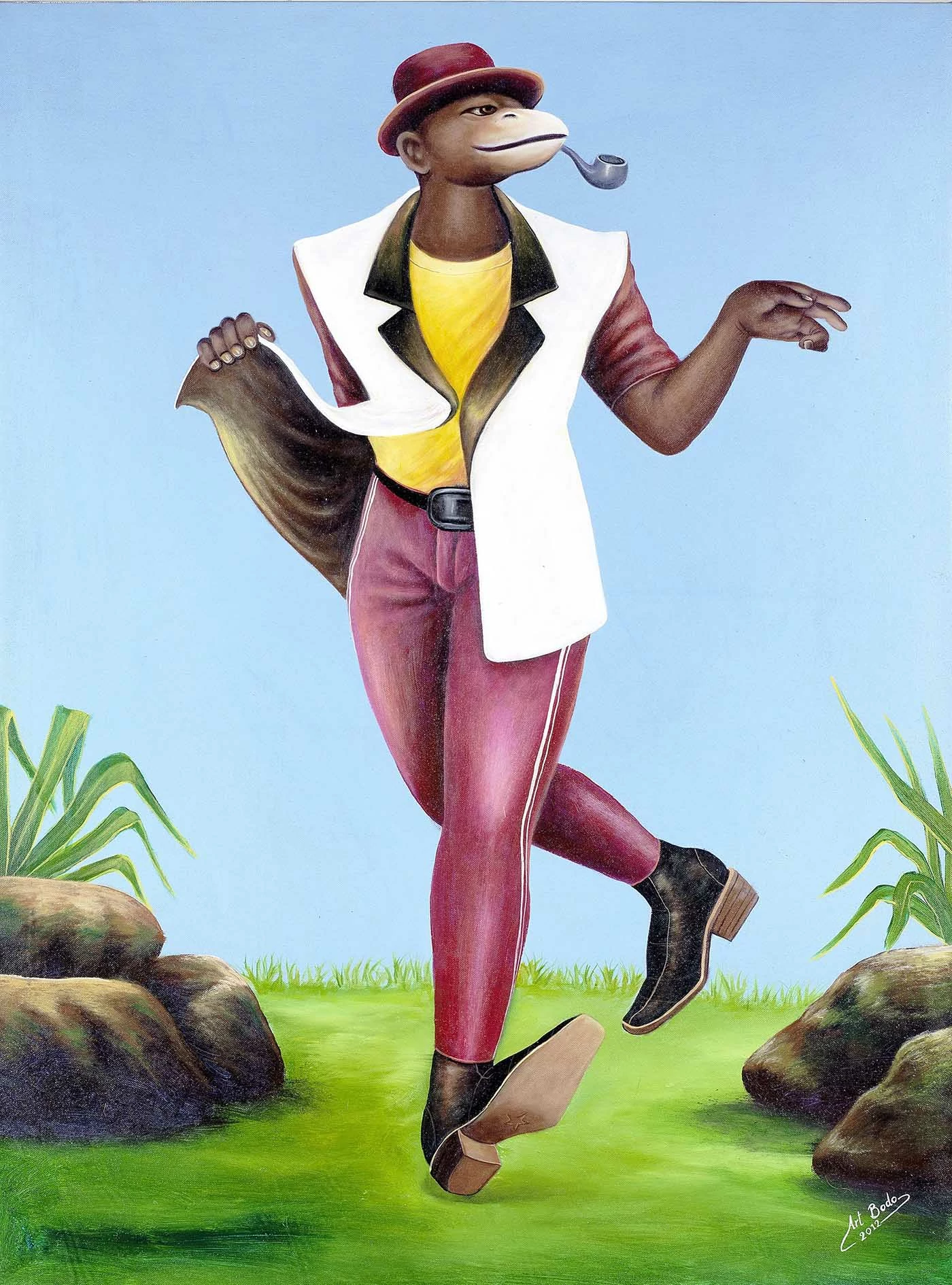

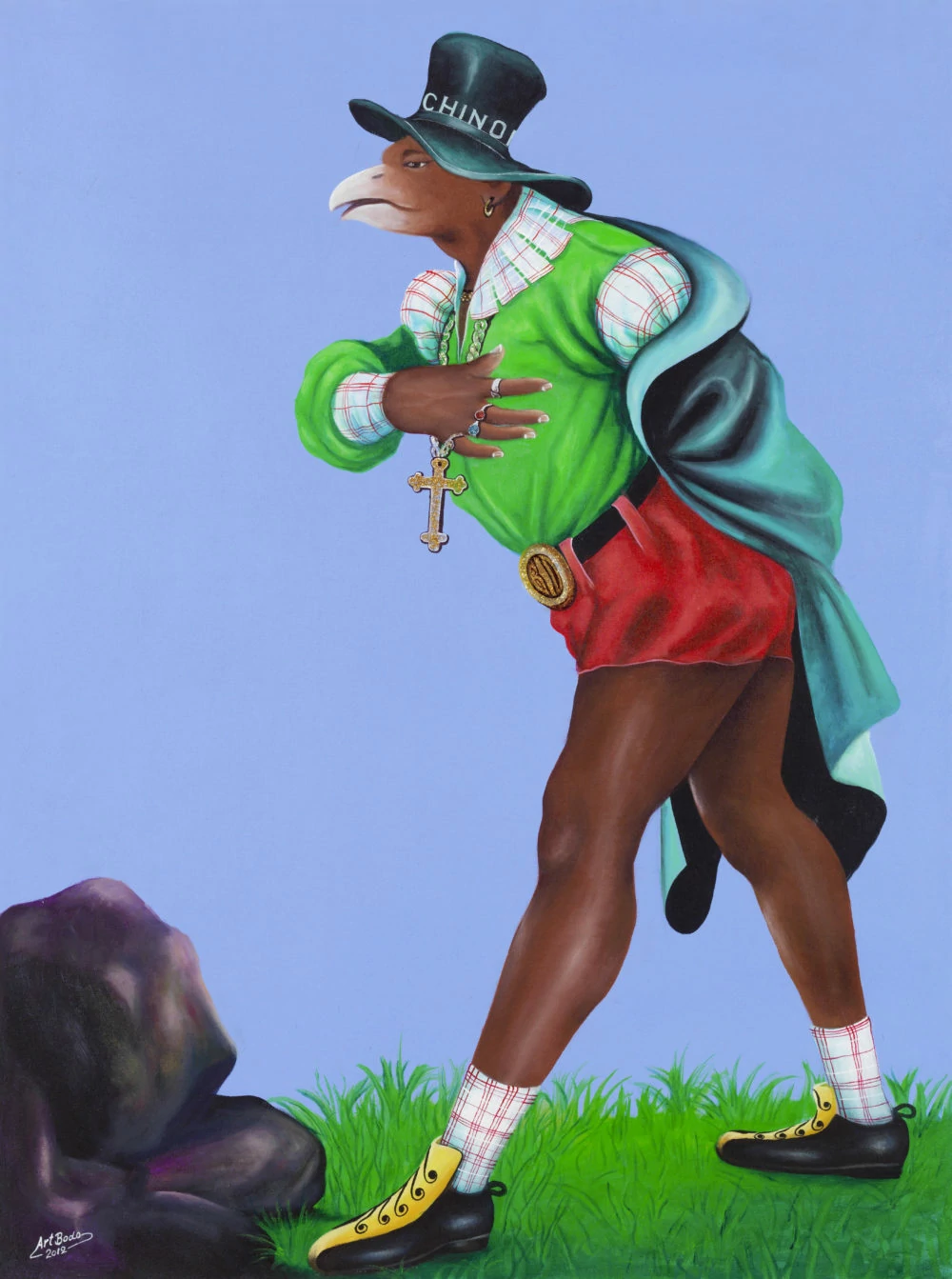

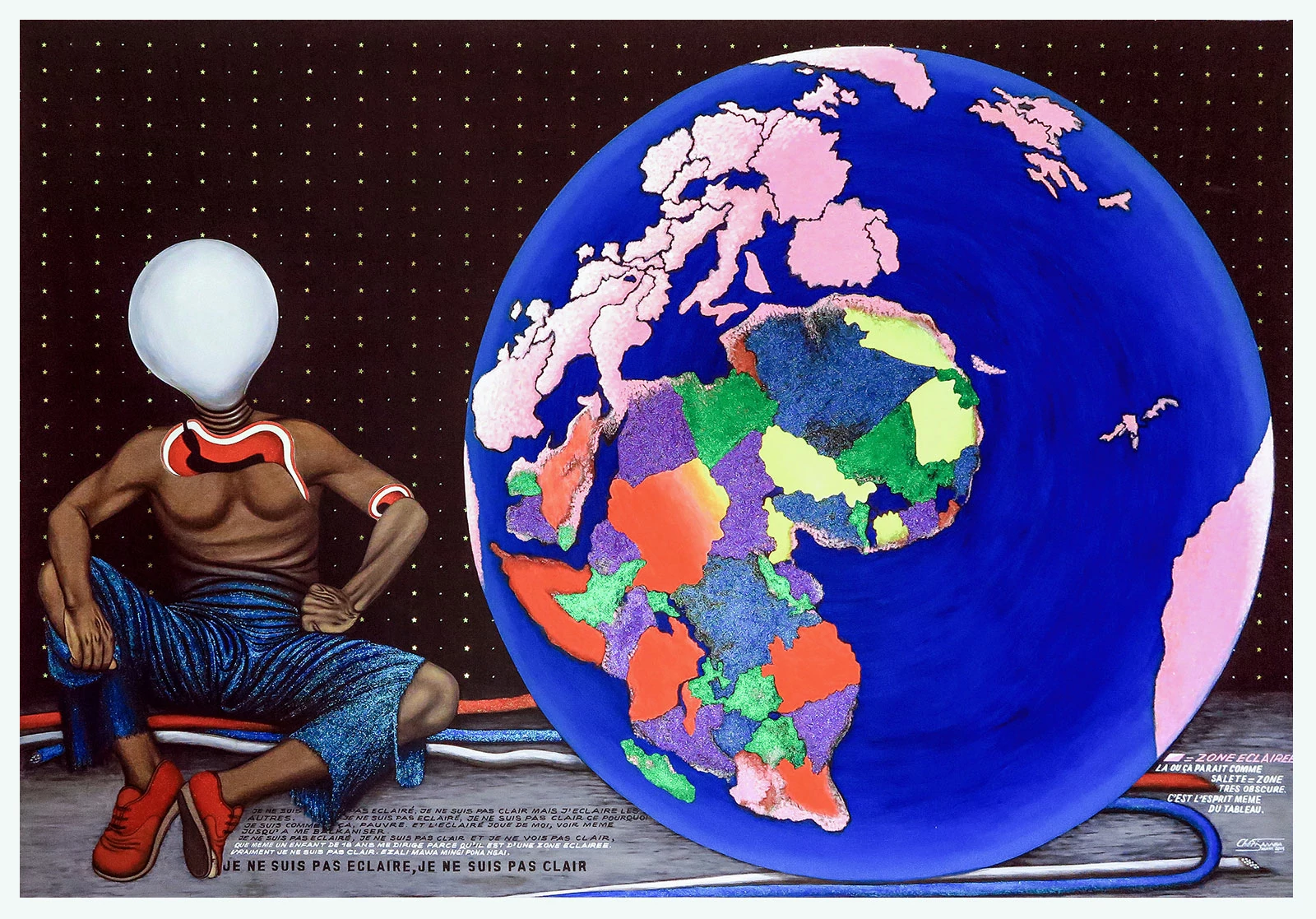

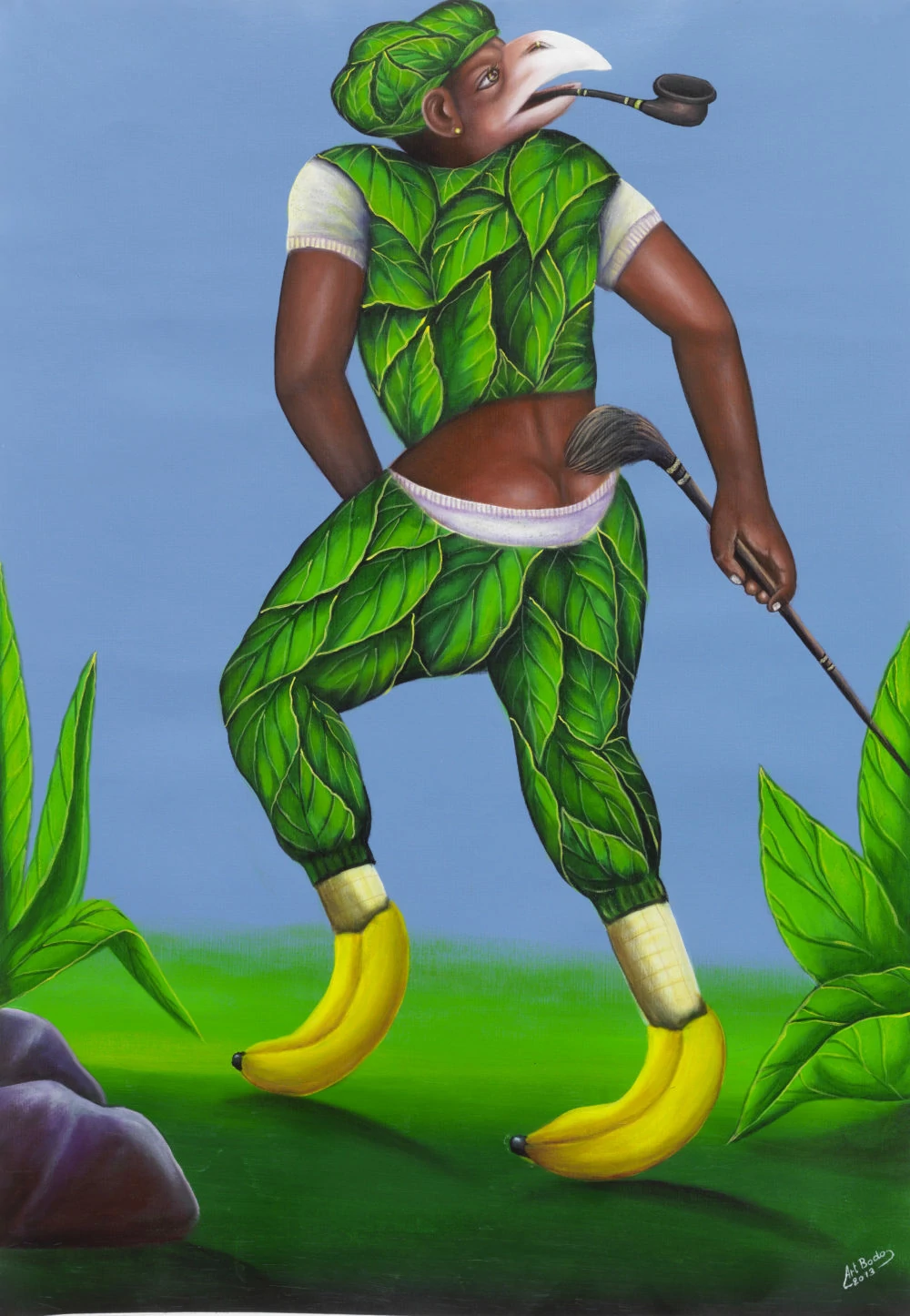

The Zaire School started small. A young artist named Chéri Samba opened a studio in Kinshasa, the DNC capital, painting billboards, making comic-strips, and combining these graphic styles in paintings on burlap. In Kinshasa, Samba was joined by the self-taught local artists Moké and Bodo, brought together by the desire to capture the day-to-day struggles, joys and politics of life in the Congo.

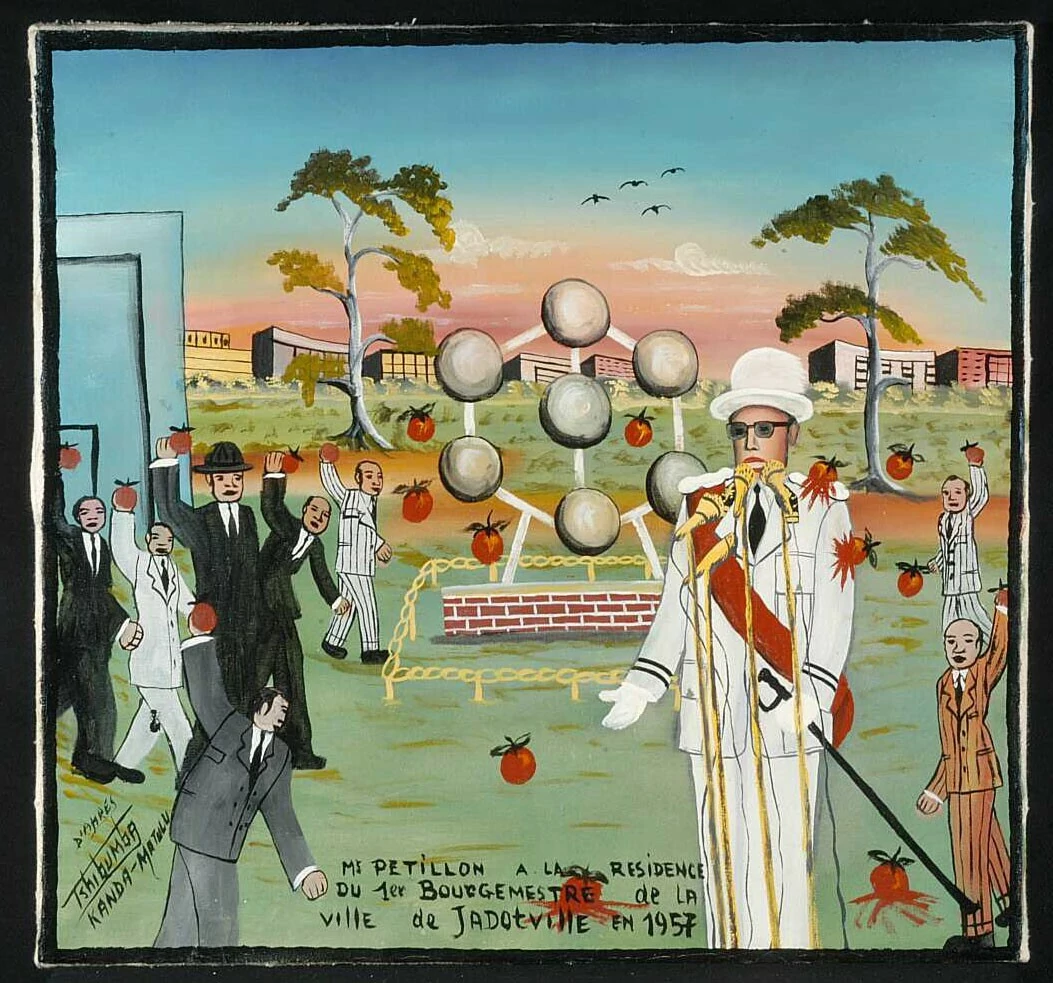

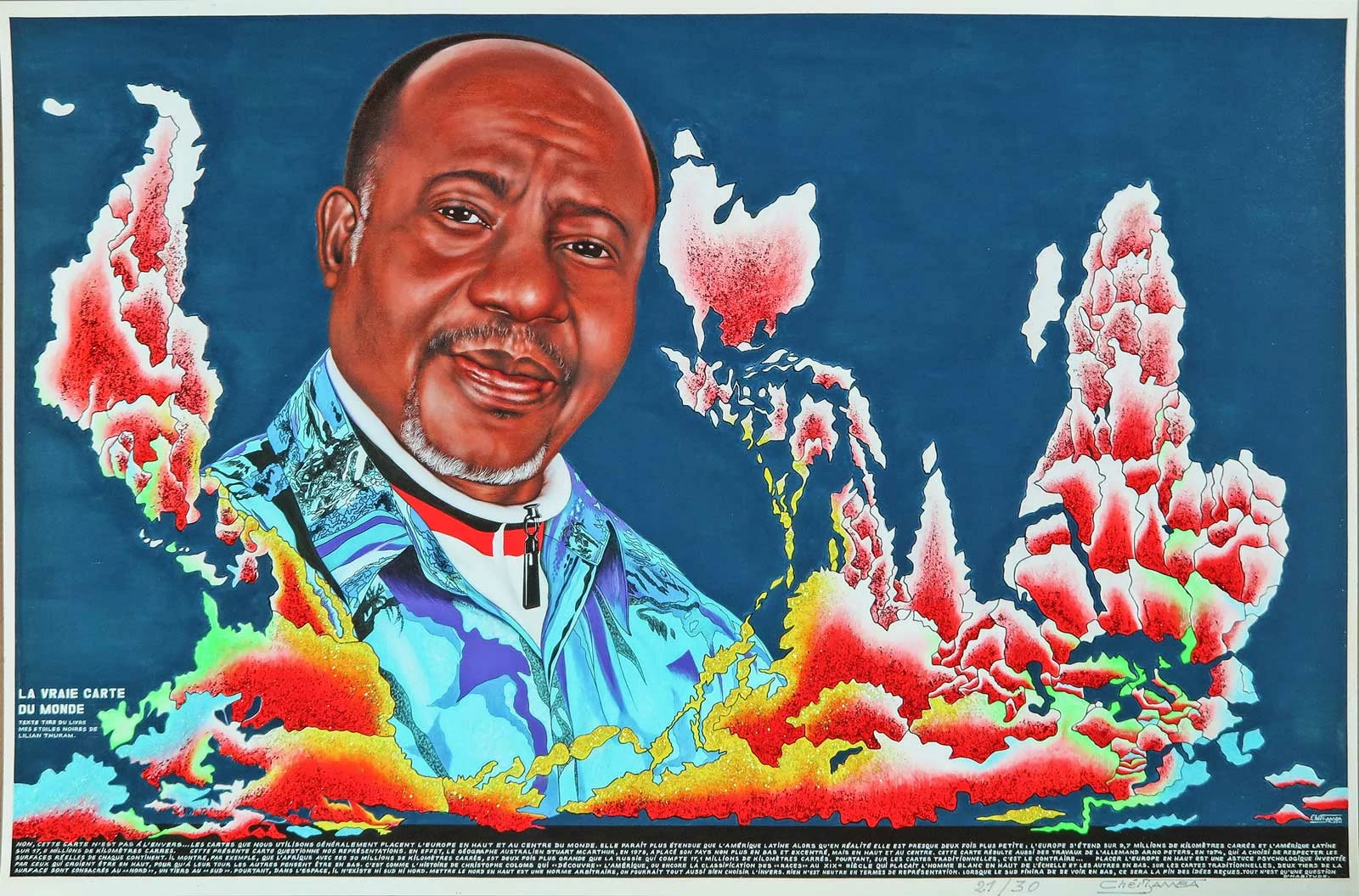

The result was an artistic style unlike any other—raw, colorful, and intensely didactic. Zaire School artworks are often extremely literal, depicting specific people and events and using painted text to label key information about the scene. This is not art to interpret or speculate on, it’s education. Samba described the use of labels saying, “The texts that I introduce on my canvases translate the thoughts of the people I depict in a given situation. It is a way of not allowing freedom of interpretation to a person who looks at my painting.” Fitting for artwork that emerged from a country held hostage and voiceless for so long.

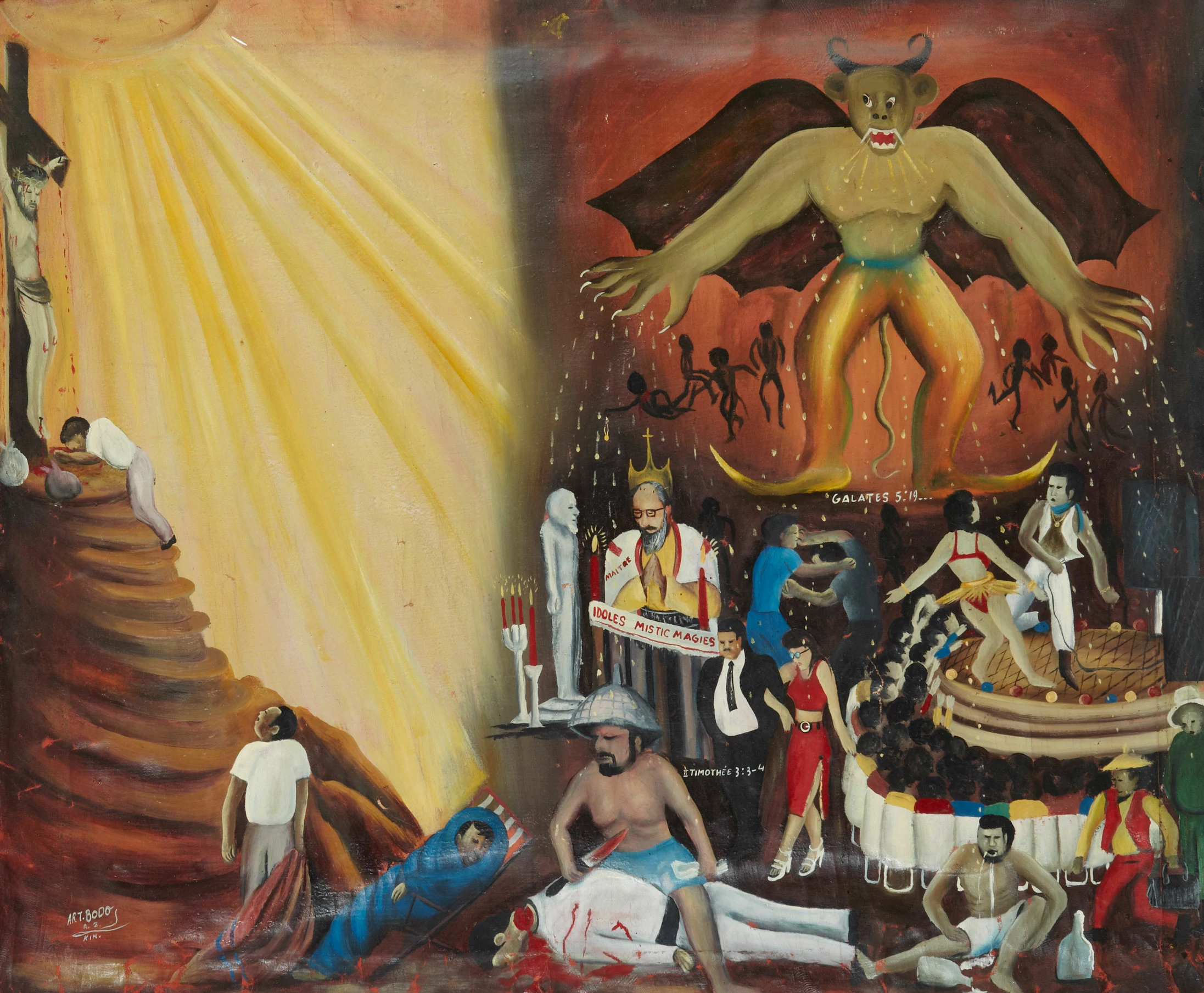

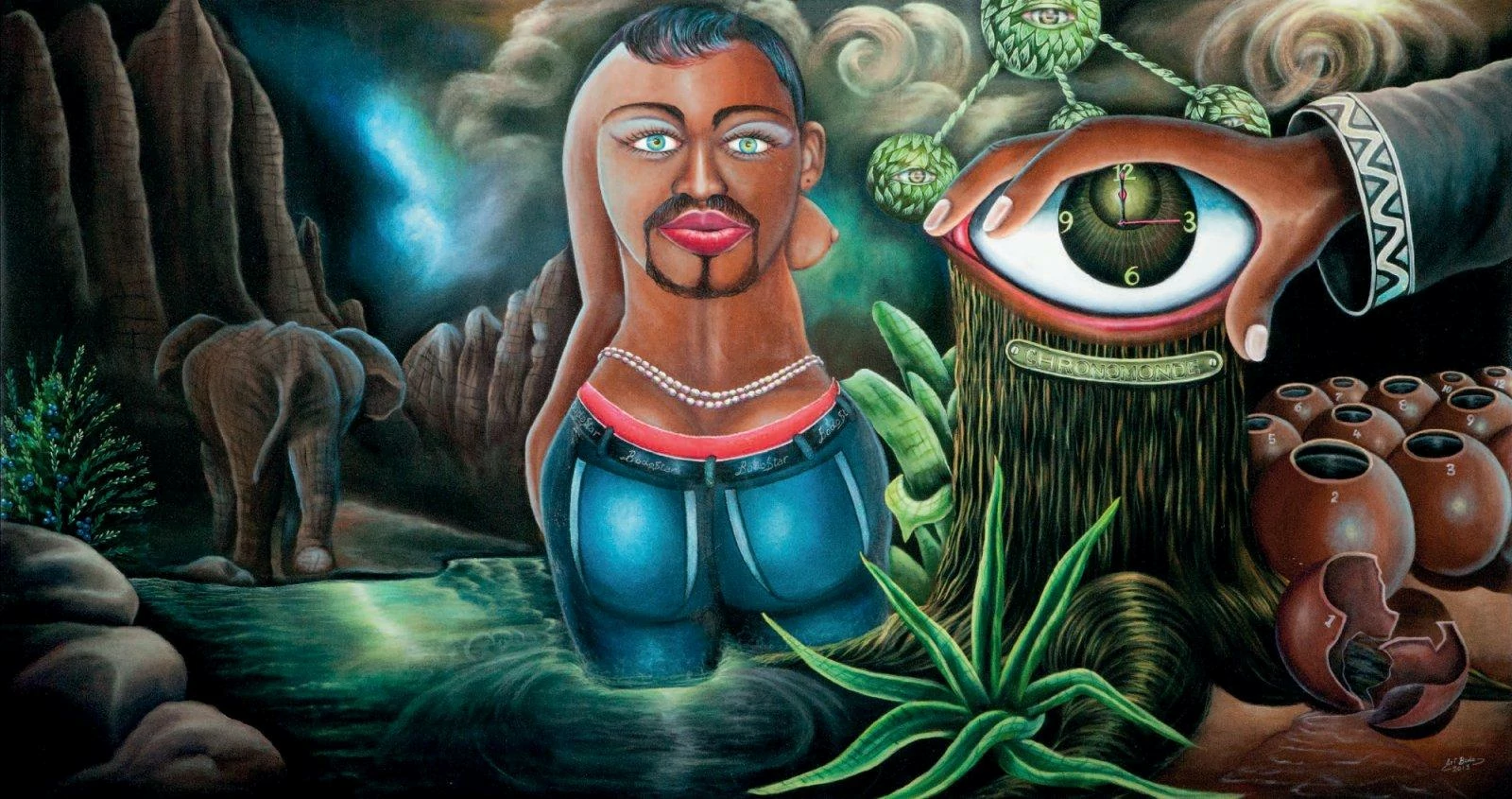

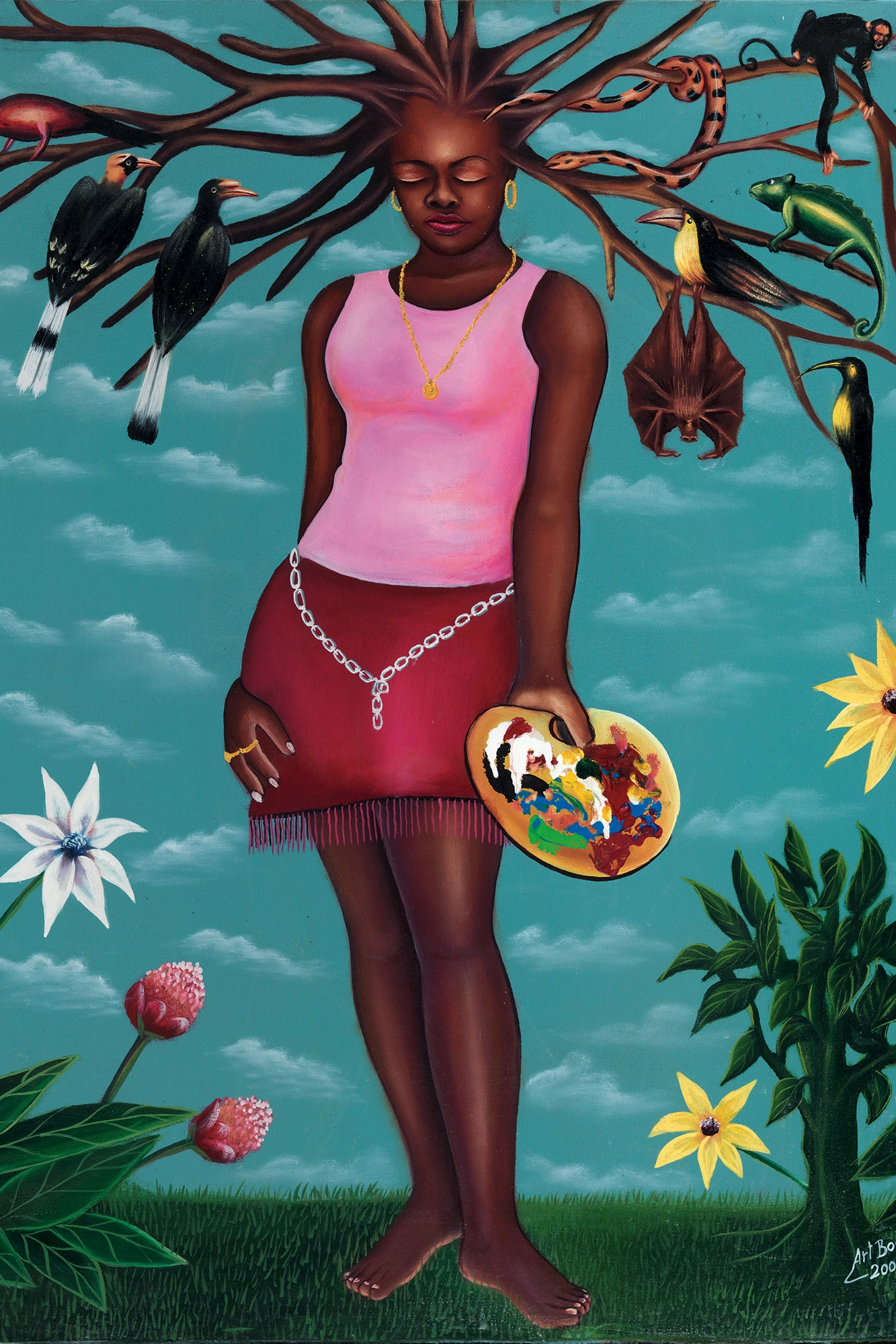

But the Zaire School wasn't exclusively political. Moké documented the social life in Kinshasa’s outdoor bars, and Bodo became a Pentacostal Christian and created surreal compositions intended to decry the local practice of sorcery.

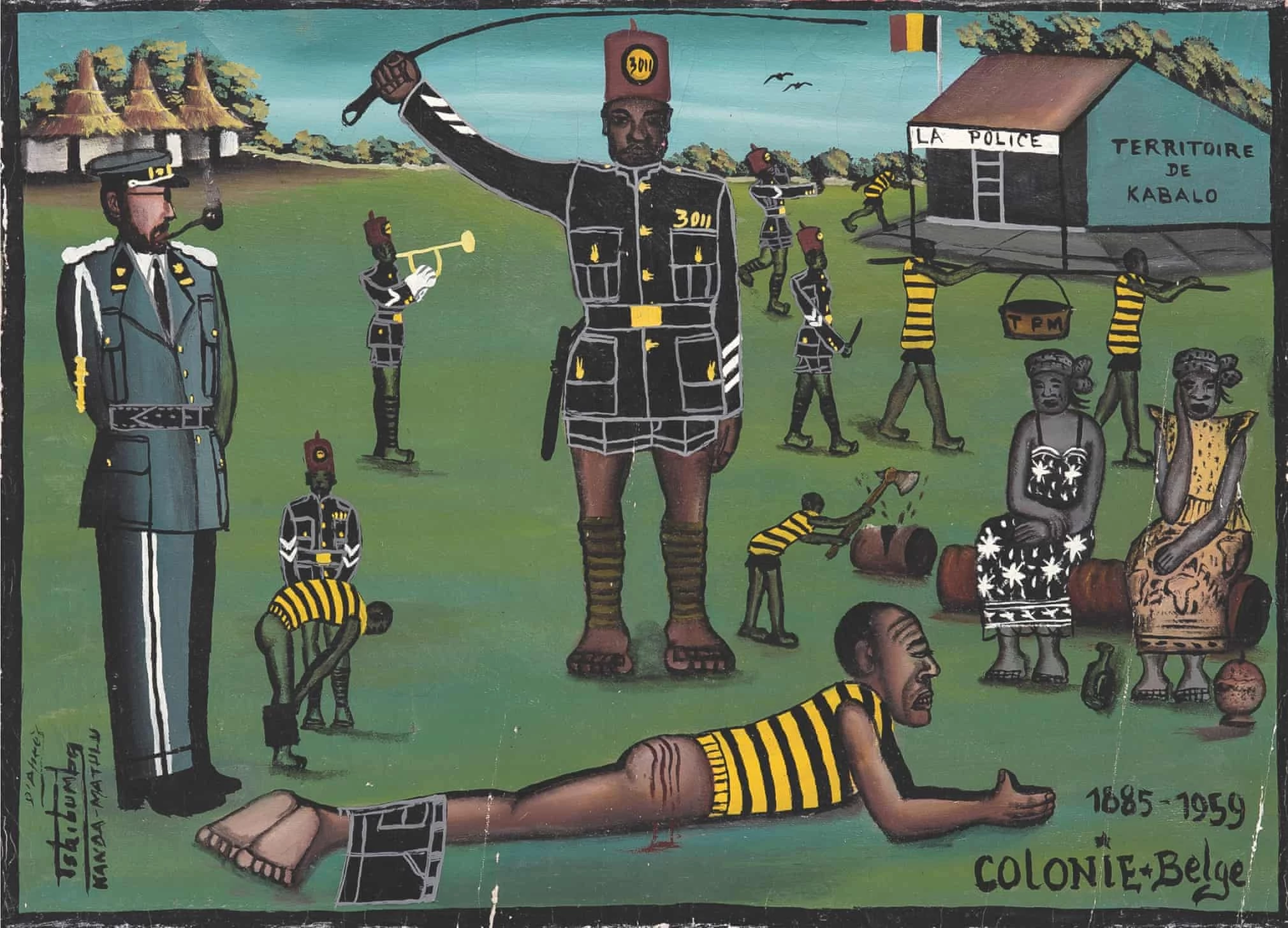

In 1970, Tshibumba Kanda Matulu contributed a massive, influential body of work to the Zaire School. Matulu was commissioned by Johannes Fabian, a professor of Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam, to create a visual history of the Congo. The final collection of 101 artworks is an enormously powerful record of colonial abuse, post-independence conflicts and Congo’s pre-colonial past.

The Zaire School of Popular Painting is no longer a formal group, since Kanda Matulu disappeared in the early 1980s and Moké and Bodo died in 2001 and 2015. But the bold colors, honest language and energetic visions of Chéri Samba, Chéri Chérin, and other Congolese artists continue to share the populist voice of the DR Congo with the world.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Zaire School of Popular Painting? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.