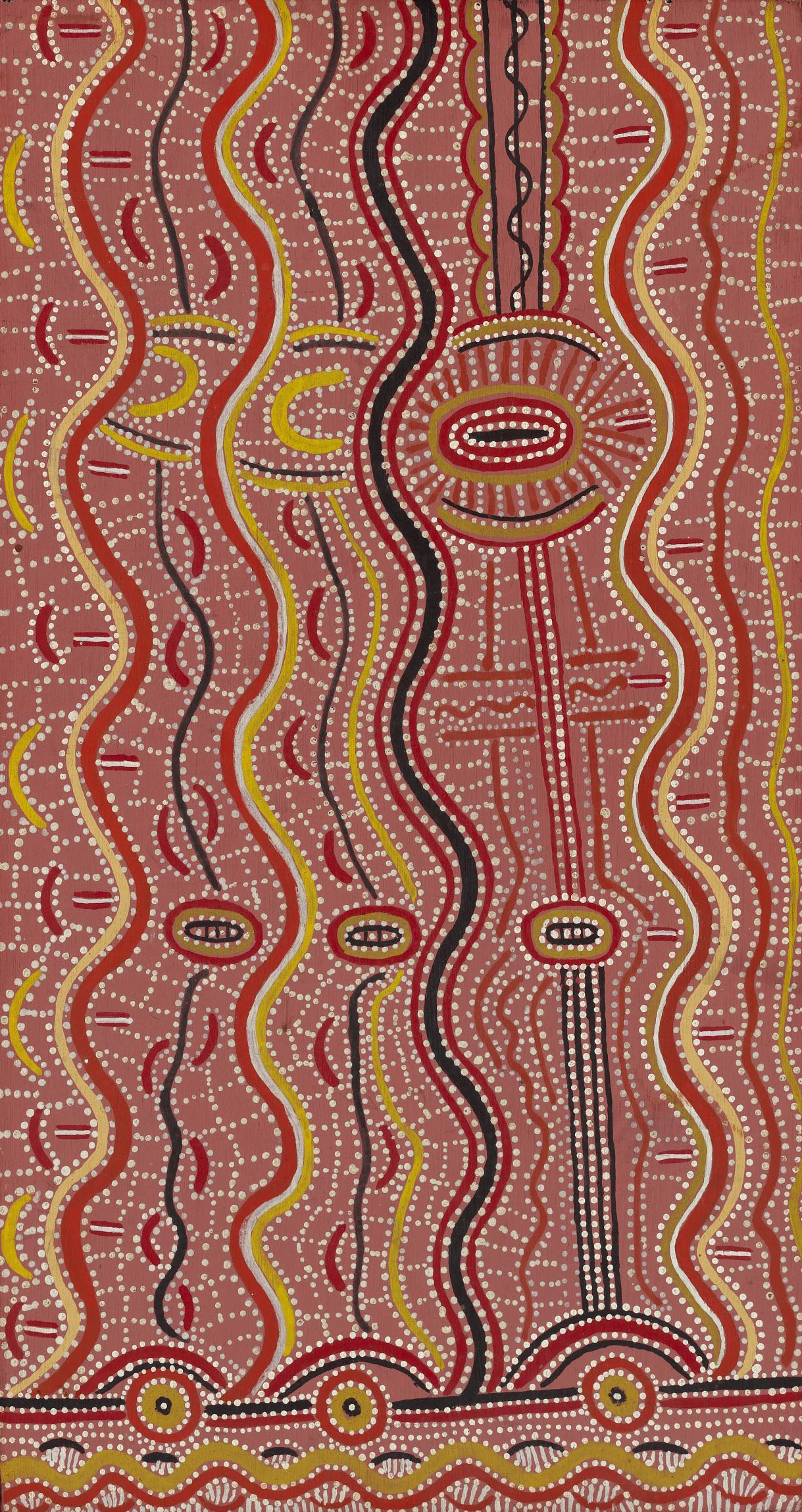

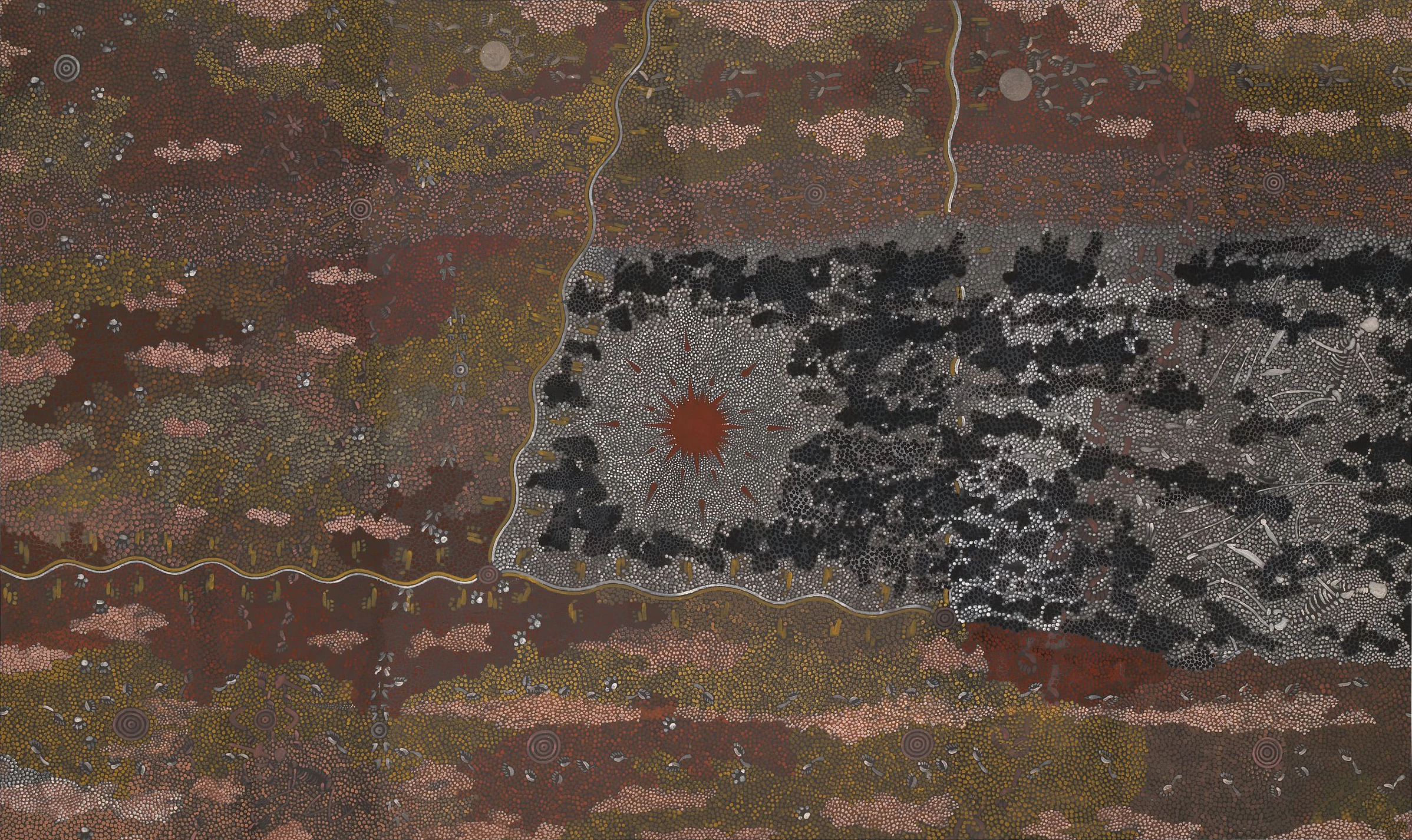

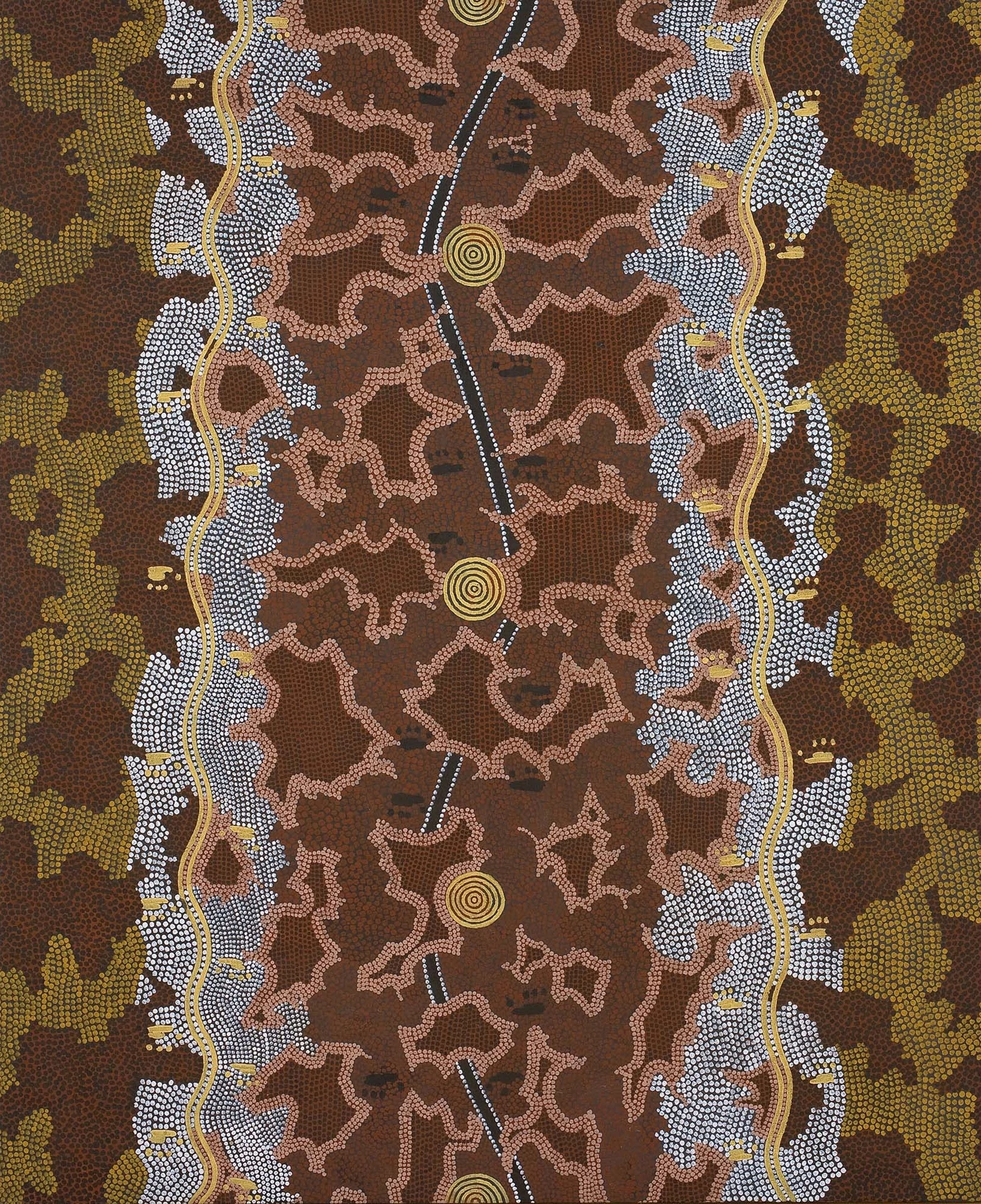

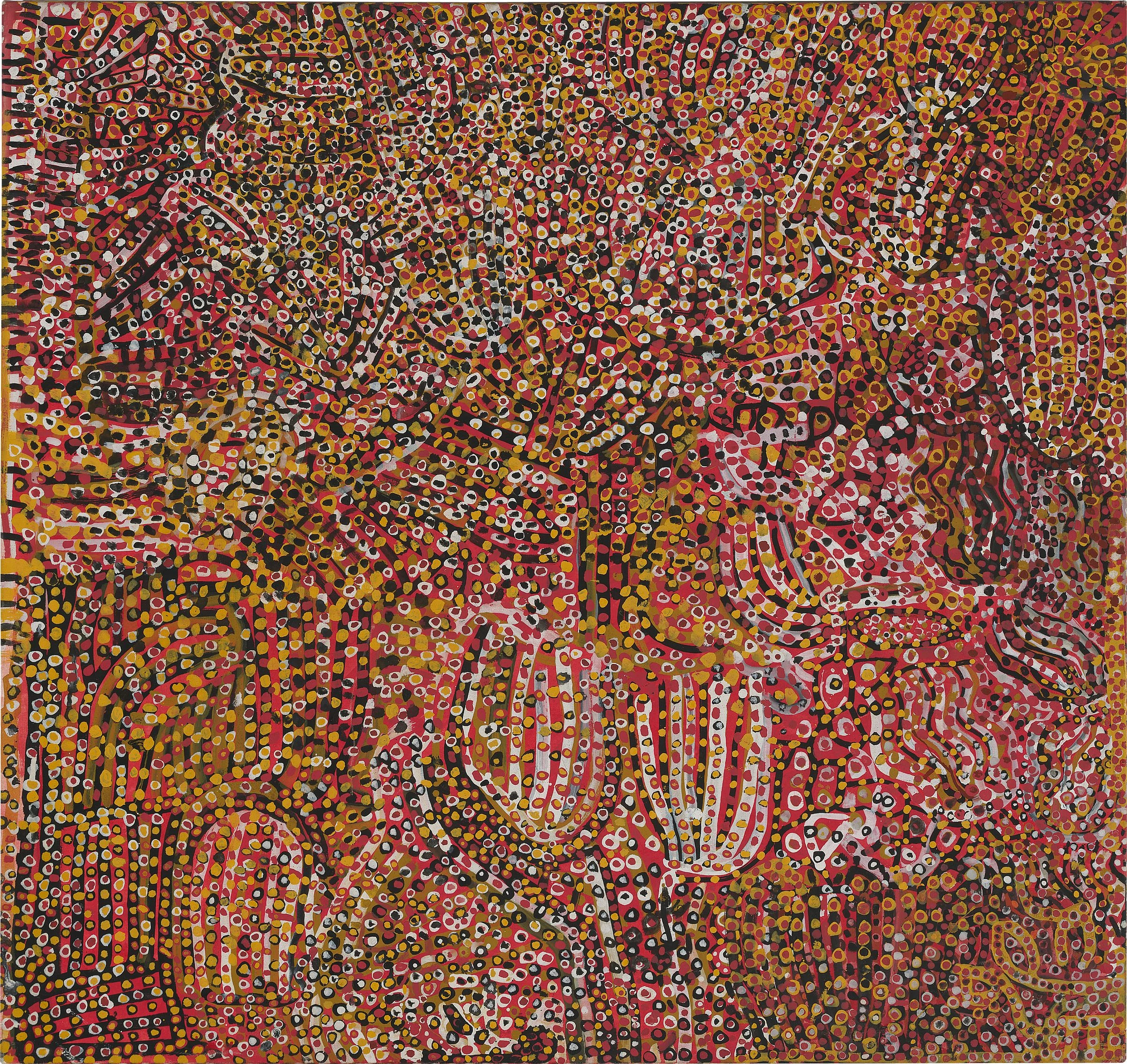

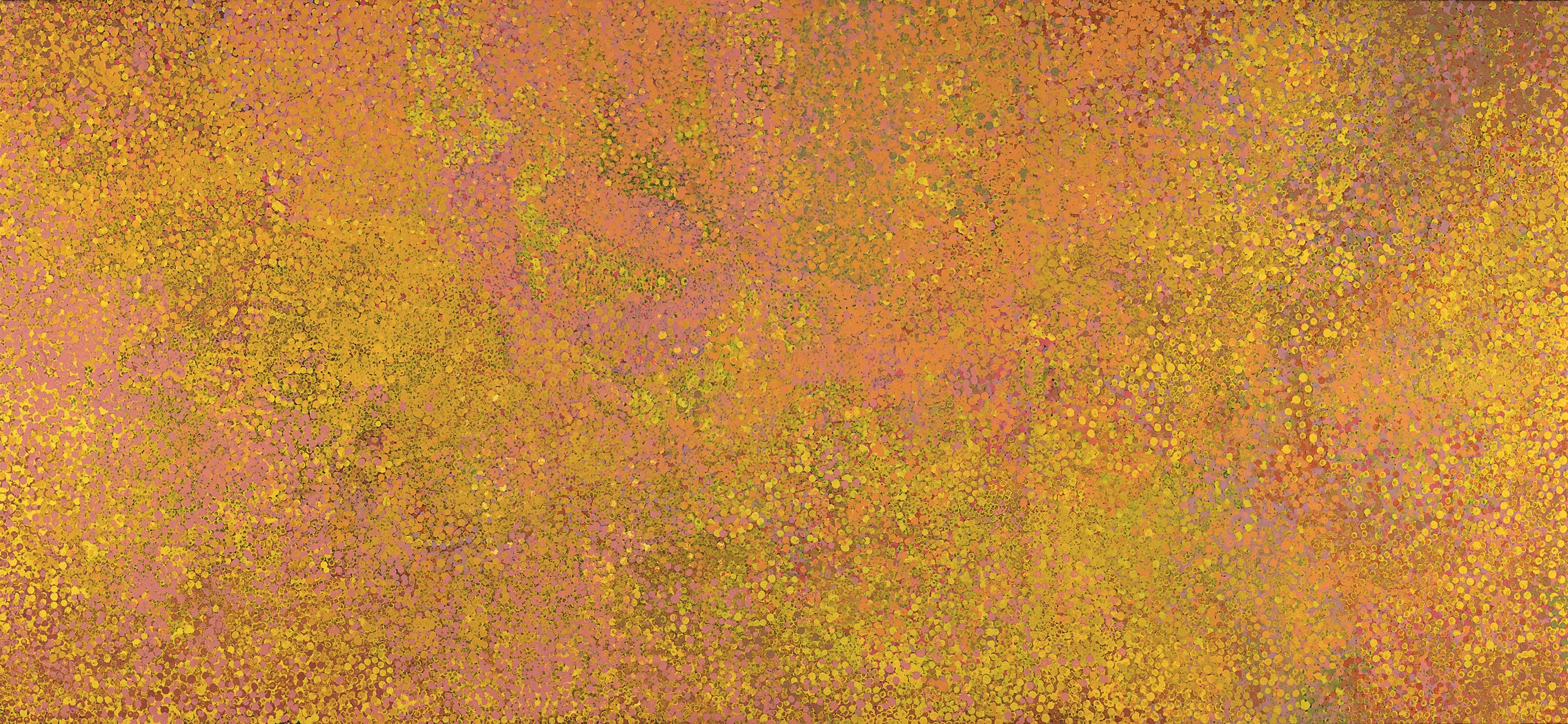

Contemporary Indigenous Australian Art

Mapping the Dreaming

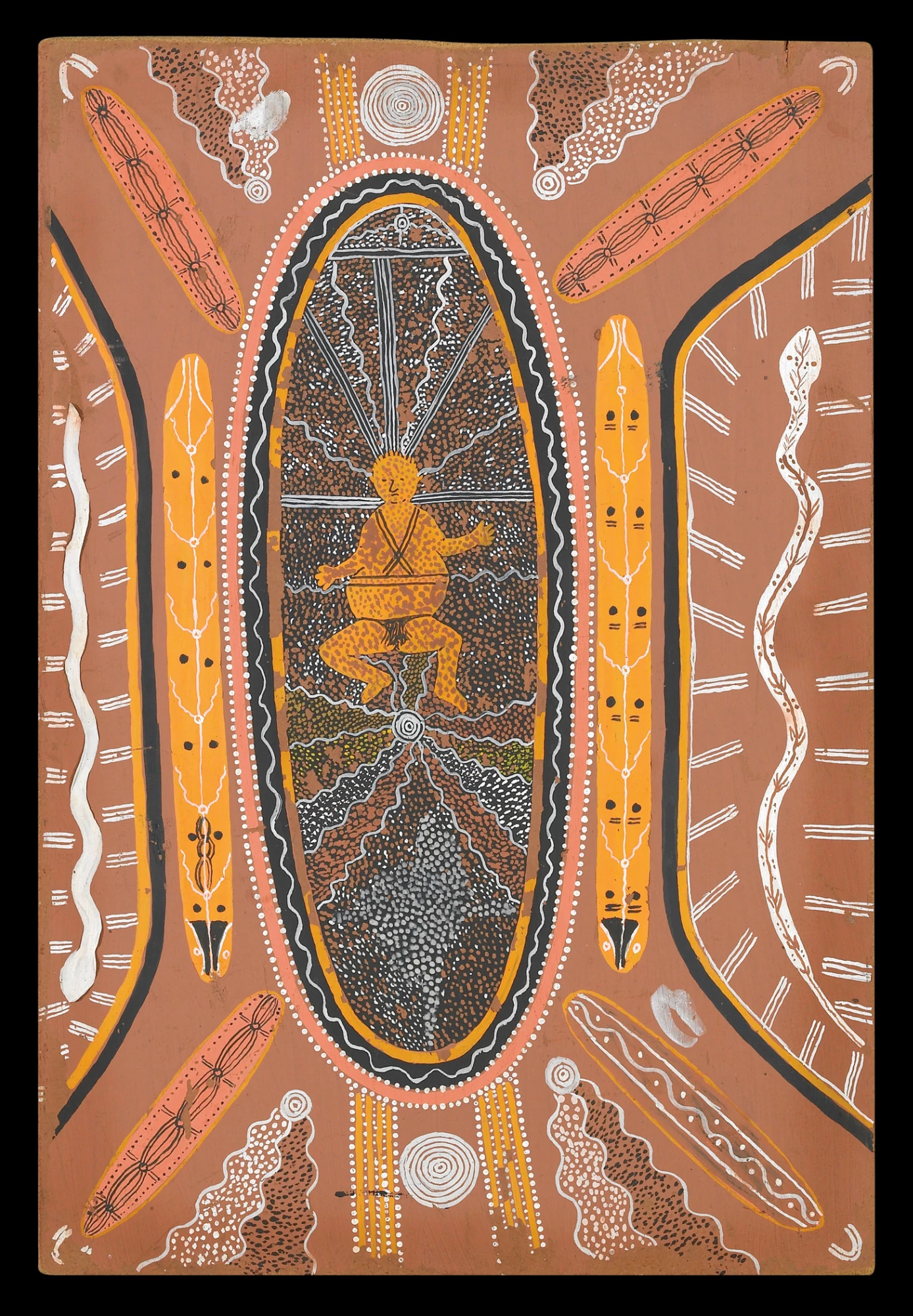

Long ago, the Ancestors emerged from eternity into a cold, dead world. In the first days they broke through the crust of the earth to wake the sleeping things below. The sun rose, and revealed the Ancestors to be chimera—human and creature and plant. Traveling across the earth, they created the mountains, rivers, trees and plains, and shaped the ants, eagles, possums, lizards, and snakes. They created humans, and the quandong and yam and edible plants to sustain them. This was the beginning.

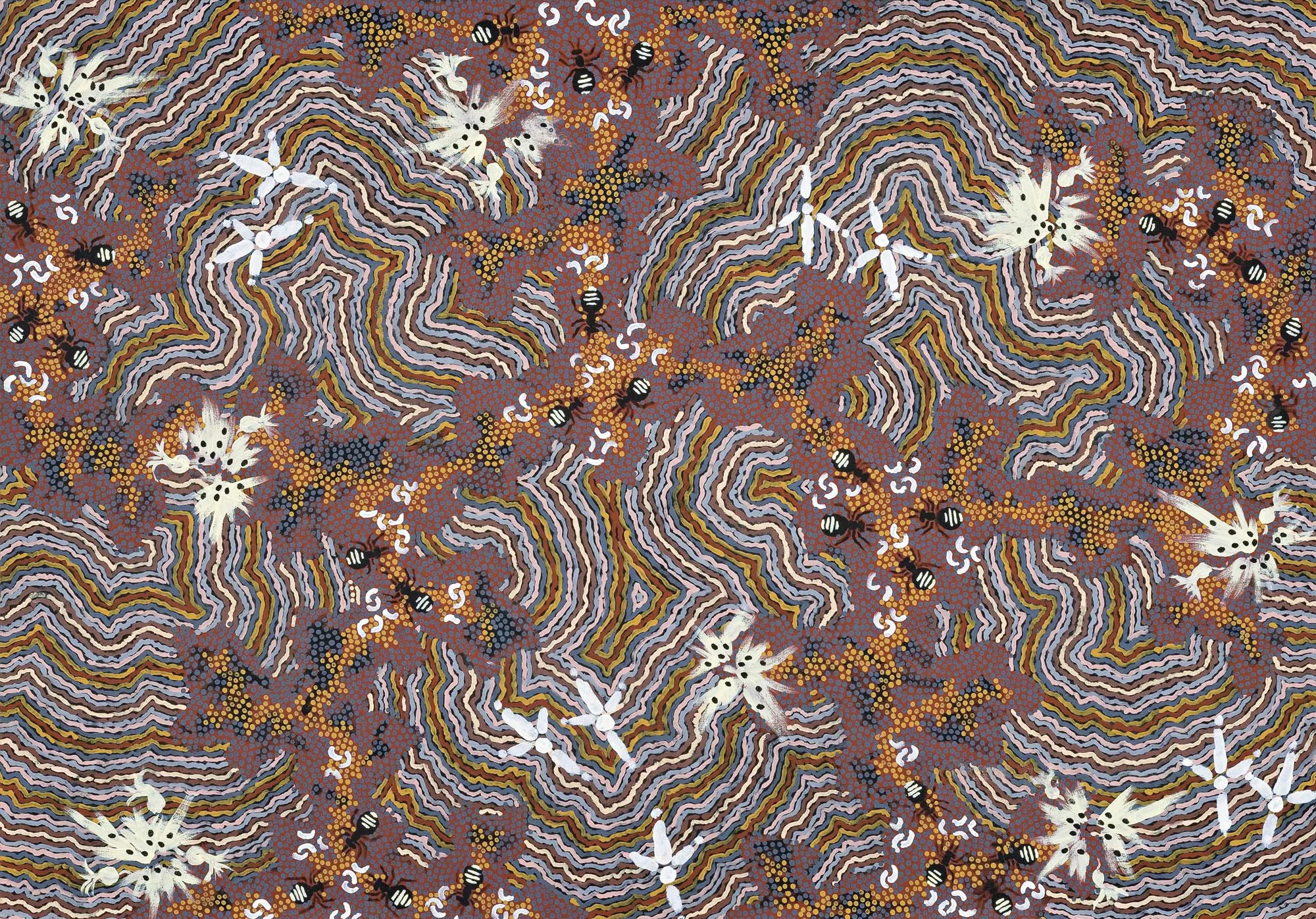

When the Ancestors grew tired, they sank into the earth or sheathed themselves in the form of a tree or stone, and these places became sacred. Human tribes emerged, each with stories and songlines between sacred places, but they were all tied to the land, the plants, animals and each other. This sacred totality, all things bound to the land then, now, and in the future, has been called different things by different people groups—Jukurrpa by the Warlpiri, Tjukurpa by the Pitjantjatjara people, Aldjerinya by the Arrernte, and Nguthuna by the Adnyamathanhaand.

The English language has no word to adequately describe a worldview that blends mythological history with contemporary reality, unifying kinship structures, morality and ethics—so we refer to it as the Dreaming. As described by Jeannie Herbert Nungarrayi, a Warlpiri teacher:

“[The Dreaming] is an all-embracing concept that provides rules for living, a moral code, as well as rules for interacting with the natural environment.The philosophy behind it is holistic – the Jukurrpa provides for a total, integrated way of life. It is important to understand that, for Warlpiri and other Aboriginal people living in remote Aboriginal settlements, The Dreaming isn’t something that has been consigned to the past but is a lived daily reality.”

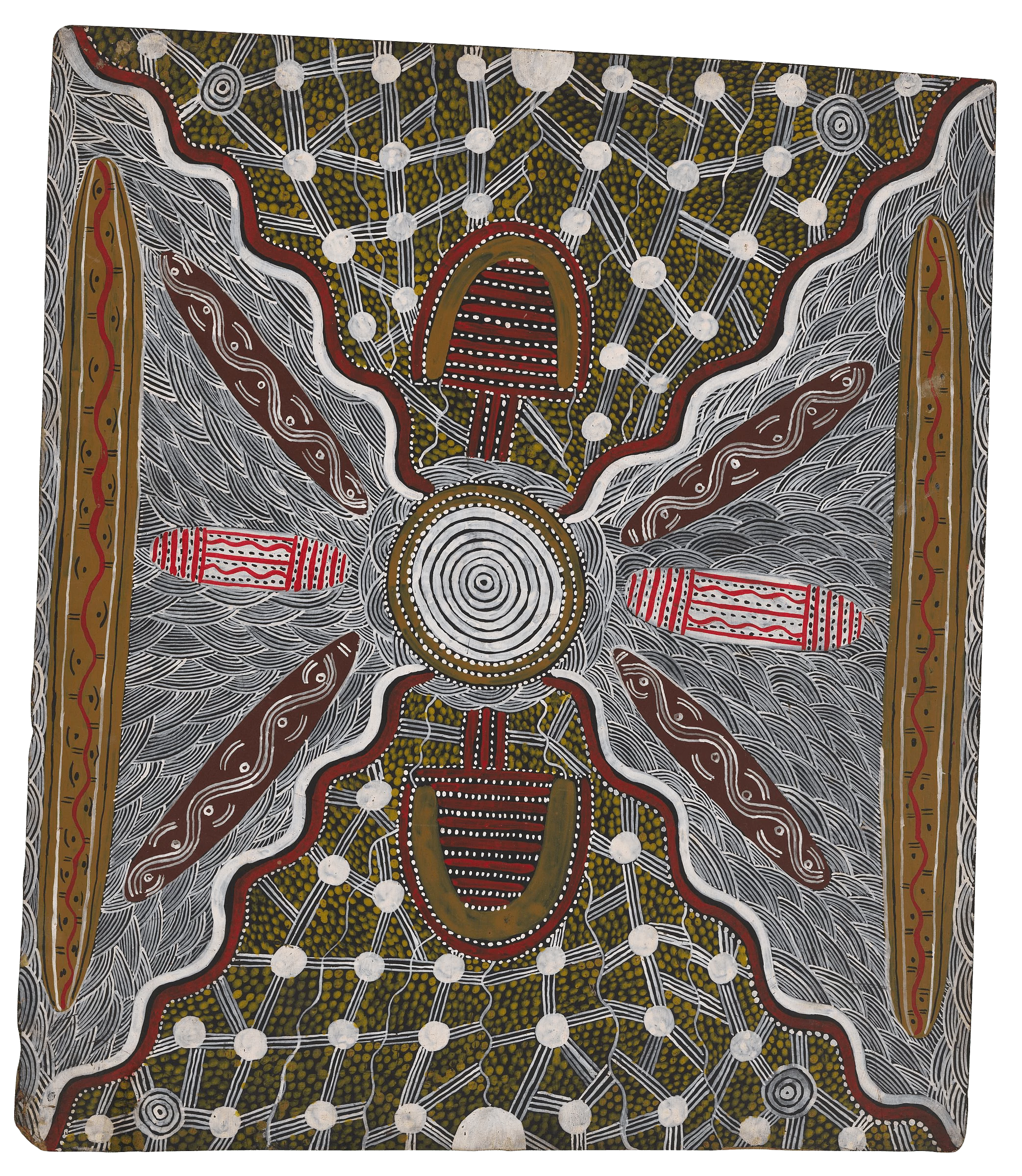

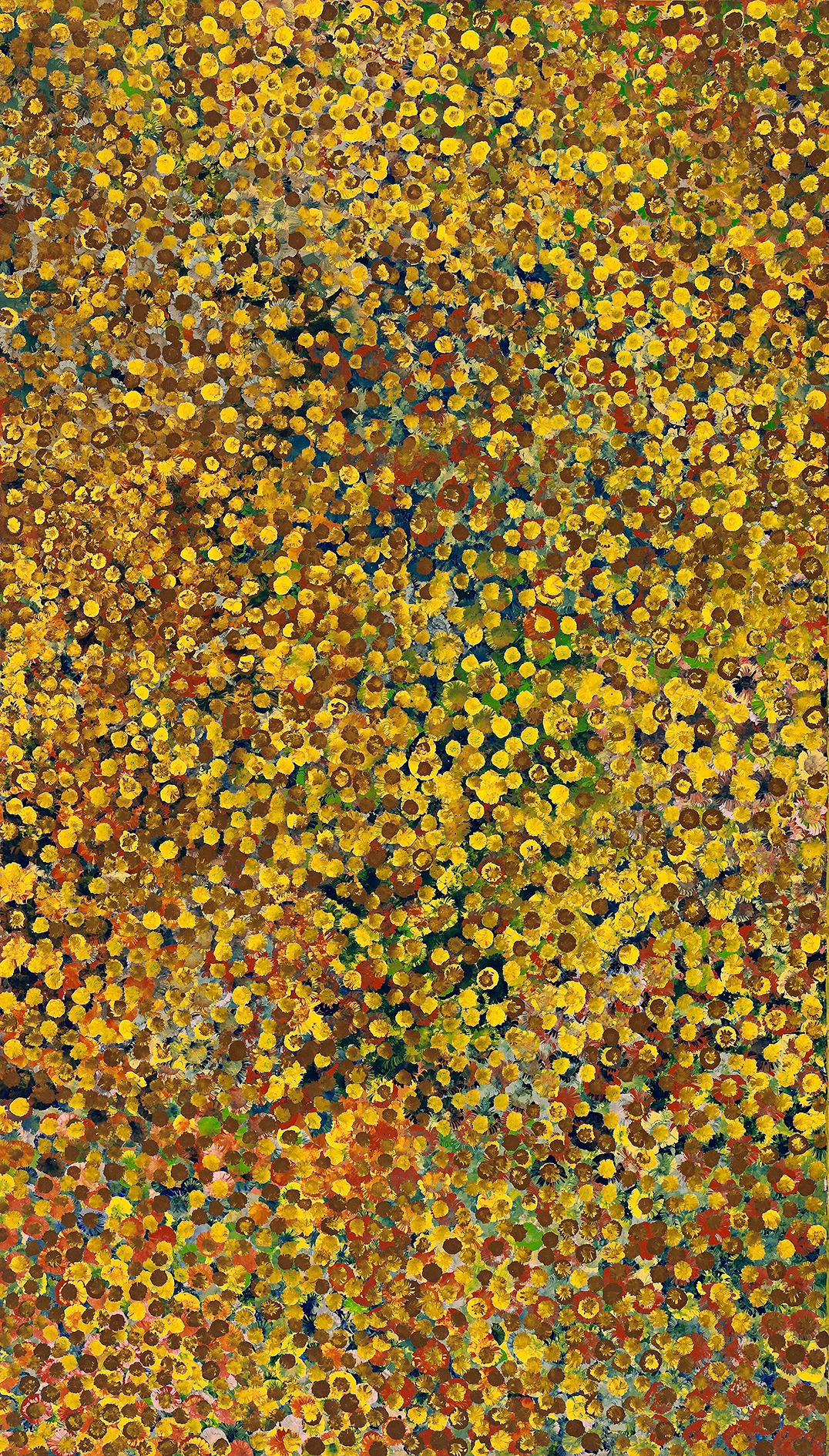

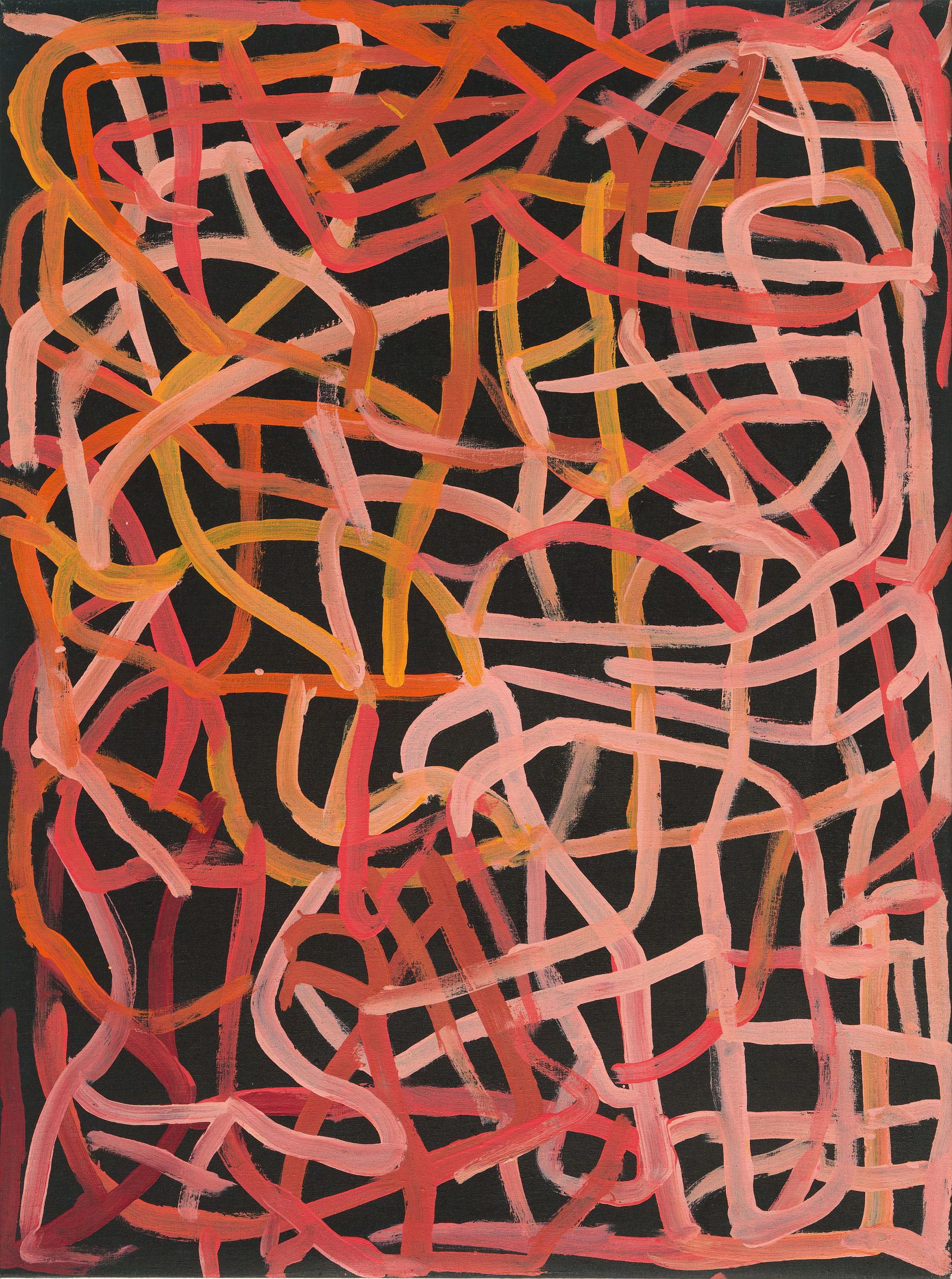

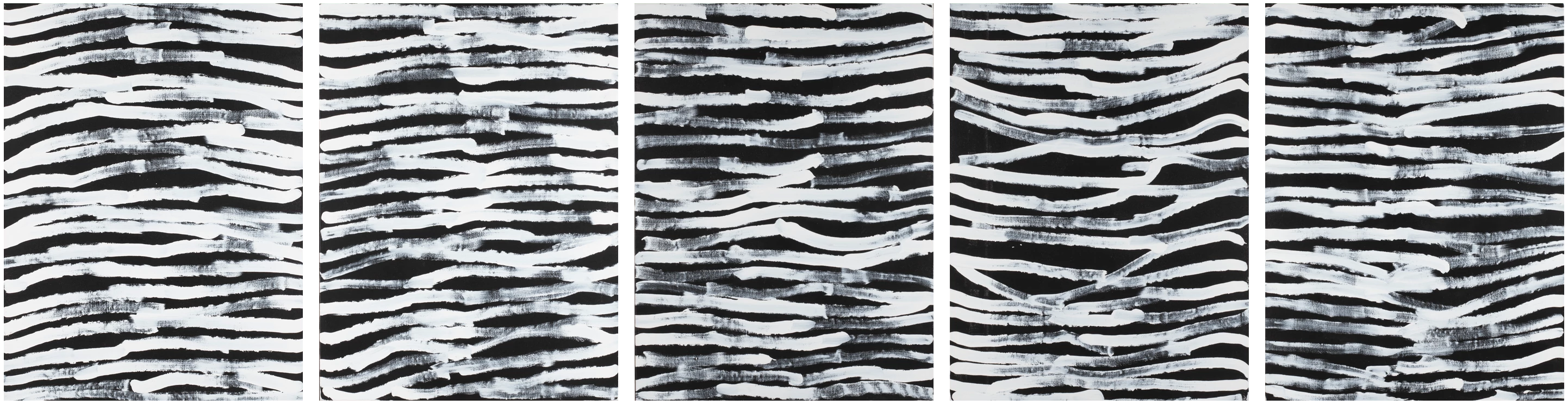

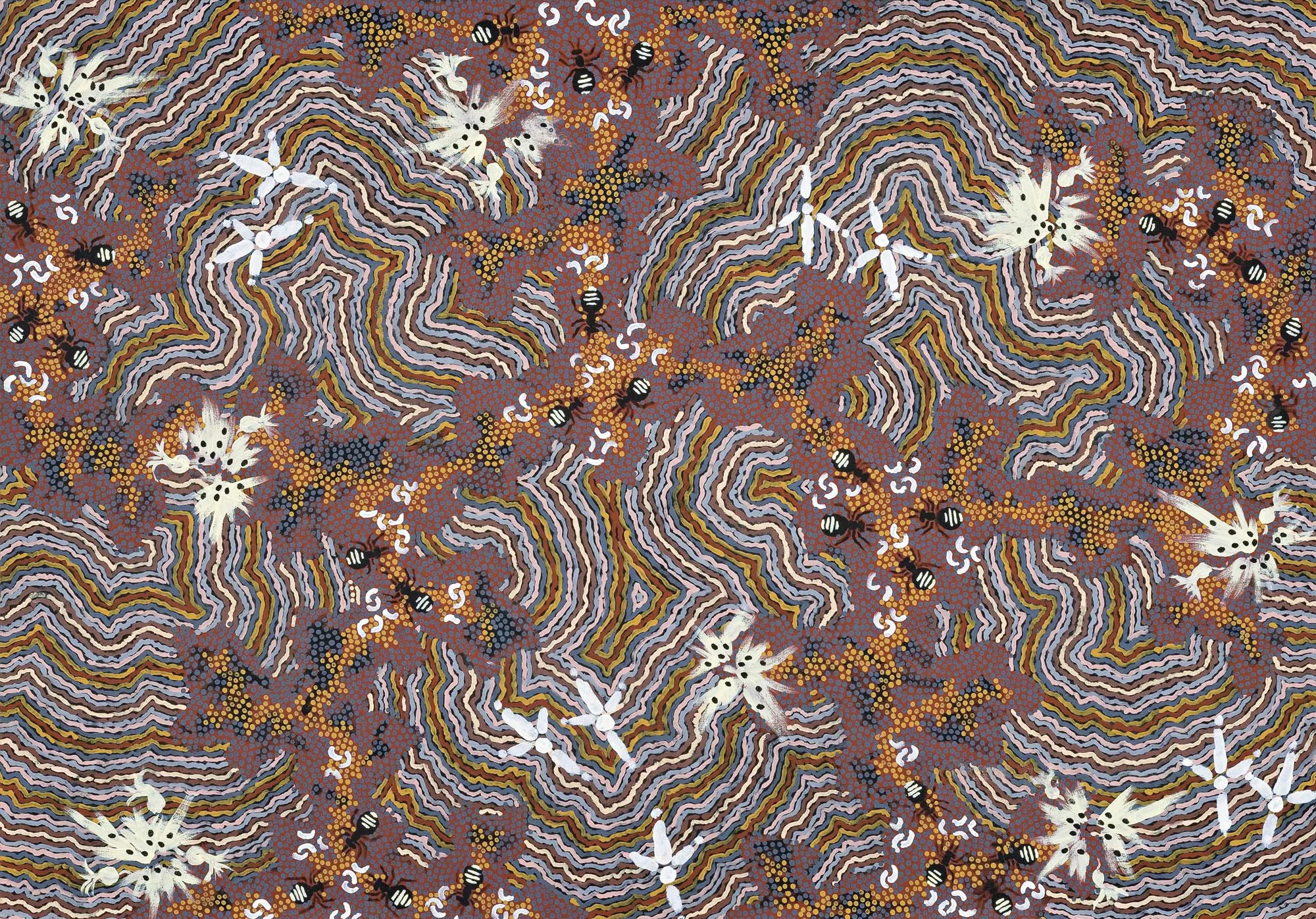

When approaching contemporary indigenous Australian art, you must begin with the Dreaming, because without it, the creative explosion that emerged from Australia in the 1980s looks a lot like abstract art. Swirling patterns, layers of colored dots and hints of iconography look right at home in polished New York galleries alongside the inescapable repetition of abstract expressionism and non-figurative color paintings. But Australia’s indigenous artists are not rehashing modernism, they are mapping the Dreaming.

The beautiful and complex cosmology of the people indigenous to Australia is the oldest continuously practiced culture in the world, dating back an estimated 50,000 years, kept alive for 50 millennia through an extraordinarily rigorous transfer of knowledge. Seasonal rituals, dance, body painting, sand drawings and the creation of baskets tools and food all are part of the Dreaming practice, supported by an oral history spanning the more than 250 languages that existed before colonization. These cultural art forms were sacred and secret, until 1971.

The movement called Western Desert Art, or Contemporary Indigenous Australian Art emerged in the bitter aftermath of colonization in Australia. Beginning in 1788 with the arrival of the British ‘first fleet’ of penal ships, Australia’s indigenous population was devastated by European diseases, massacred by the tens of thousands by white ‘hunting’ parties and the Native Police, and the rest displaced from their ancestral land and herded into state-run reservations.

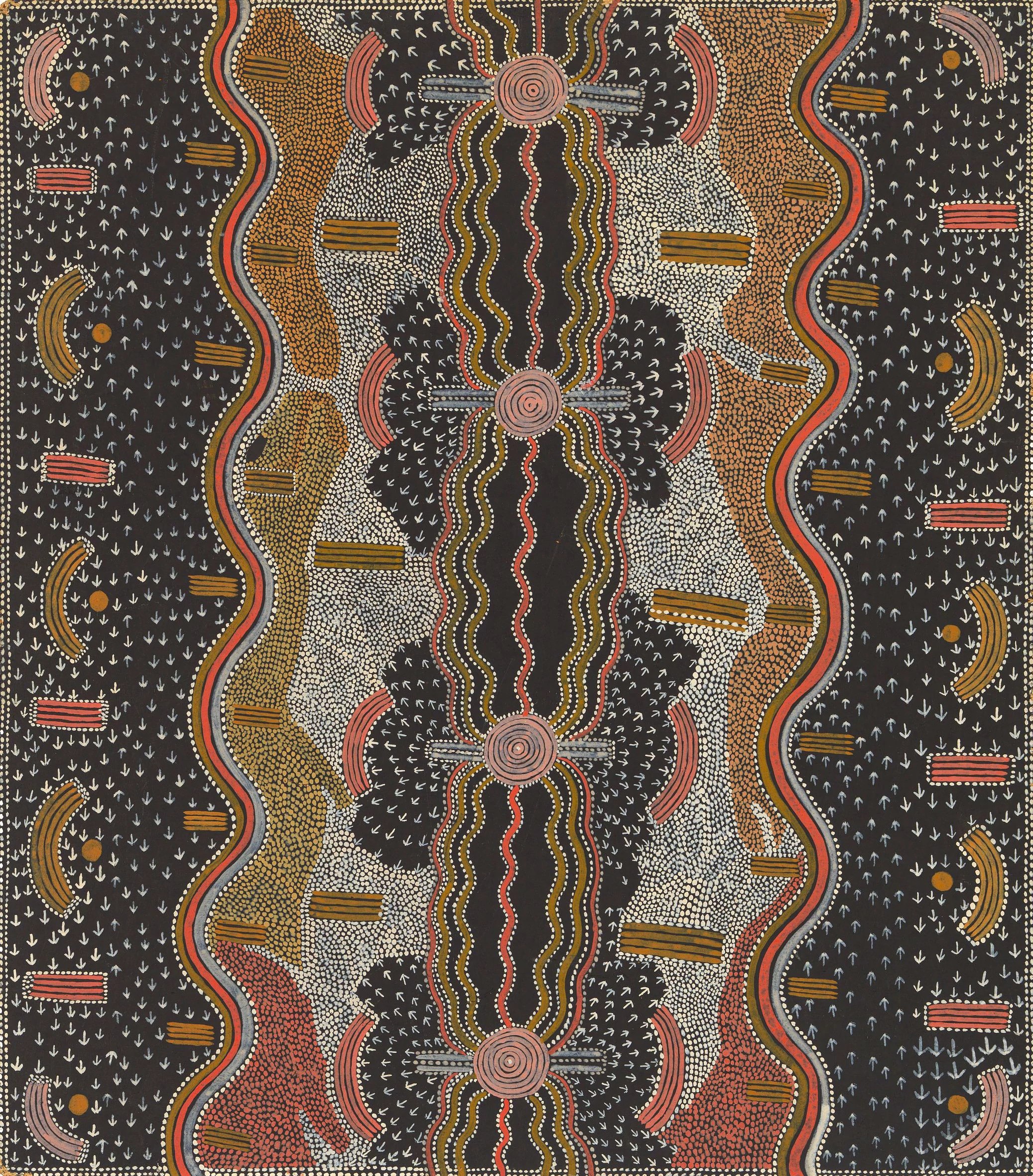

In 1971, while working on the Papunya reservation, white schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon encouraged the local children to paint a mural on the school wall in the swirling dot pattern style of the Dreaming rituals. The local elders discovered the project and took the reins, transforming the mural into a depiction of Papunya’s location in the Dreaming—a convergence of songlines called the Honey Ant Dreaming. The same year, Papunya’s troublemaker-artist-thief, Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, won the Caltex Art Award for his painting Men’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo, Gulgardi. Soon, more than 20 Papunya men were transcribing the Dreaming onto wood and canvas.

It took a decade before the Papunya artists gained large-scale recognition, but in the 1980s the burgeoning movement exploded, with art communities appearing in the towns of Yuendumu, Lajamanu and Balgo, and the Utopia and Ikuntji regions. In an art world monopolized by the western ideal of the independent artist toiling alone in their studio, the indigenous artists worked together, sharing techniques, supplies, and the profits from sales.

In 1994, Emily Kngwarreye, one of the leaders of the Utopia Women’s Art Collective, became the first indigenous artist to sell an artwork for more than 1 million Australian dollars. The blooming international market drove the movement forward, through Western and central Australia through the 1990s and 2000s. By 2010, the Association of Northern, Kimberley and Arnhem Aboriginal Artists (ANKAAA) registered 5000 members across 43 centers, meaning that in many indigenous settlements, 25-50% of the population was involved in making art.

As always, the success of an art movement, especially one expressing the worldview of a profoundly oppressed culture, is complicated. With success came exploitation. Kngwarreye described hiding from “carloads of ‘wannabe’ art dealers.” A 2002 a Rupert Myer report for the Australian Government estimated the value of the Australian Indigenous Art Market to be $200 million a year, with just a quarter of that finding its way back to the artists. In 2003 The Age reported ‘recruitment’ drives, where artists were offered cash or alcohol for canvases, or asked to trade canvasses for basic medical care. The same year a Melbourne gallery was discovered to have brought four indigenous artists to Melbourne, isolated them without money or transport, and then asked them to accept 1/5th the value of the artwork they created.

Today, exploitation is still a concern and the impact of commercializing an ancient tradition remains a haunting and understudied prospect, and many of the first generation Australian indigenous painters have died. But the movement continues, offering a window into the world’s oldest art practice, and a new generation of artists are looking back, planning forward, and finding their place in the Dreaming.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Contemporary Indigenous Australian Art? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.