Impressionism

Light and movement as the crux of human perception

1860 – 1900Having taken upon himself the task of seeking out and expounding the beauty in modernity, Monsieur G. is thus particularly given to portray-ing women who arc elaborately dressed and embellished by all the rites of artifice, to whatever social station they may belong. Moreover in the complete assemblage of his works, no less than in the swarming ant-hill of human life itself, differences of class and breed are made immediately obvious to the spectator’s eye, in whatever luxurious trappings the subjects may be decked.

At one moment, bathed in the diffused brightness of an auditorium, it is young women of the most fashionable society, receiving and reflecting the light with their eyes, their jewelry and their snowy, white shoulders, as glorious as portraits framed in their boxes. Some are grave and serious, others blonde and brainless. Some flaunt precocious bosoms with an aristocratic unconcern, others frankly display the chests of young boys. They tap their teeth with their fans, while their gaze is vacant or set; they are as solemn and stagey as the play or opera that they are pretending to follow.

Next we watch elegant families strolling at leisure in the walks of a public garden, the wives leaning calmly on the arms of their husbands, whose solid and complacent air tells of a fortune made and their resulting self-esteem. Proud distinction has given way to a comfortable affluence. Meanwhile skinny little girls with billowing petticoats, who by their figures and gesture put one in mind of little women, are skipping, playing with hoops or gravely paying social calls in the open air, thus rehearsing the comedy performed at home by their parents'

Now for a moment we move to a lowlier theatrical world where the little dancers, frail, slender, basally more than children, but proud of appearing at last in the blaze of the limelight, are shaking upon their virginal, puny shoulders absurd fancy-dresses which belong to no period, and are their joy and their delight.

Or at a cafe door, as he lounges against the windows lit from within and without, we watch the display of one of those half-wit peacocks whose elegance is the nation of his tailor and whose head of his bather. Beside him, her feet supported on the inevitable footstool, she his mistress, a great baggage who lacks practically nothing to make her into a great lady—that ‘practically nothing’ being in fact ‘practically everything', for it is distinction. Like her dainty companion, she has an enormous cigar entirely filling the aperture of her tiny mouth. These two beings have not a single thought in their heads. Is it even certain that they can see? Unless, like Narcissuses of imbecility, they are gazing at the crowd as at a river which reflects their own image. In truth, they exist very much mote for the pleasure of the observer than for their own.

And now the doors are being thrown open at Valentino’s, at the Prado, or the Casino (where formerly it would have been the Tivoli, the Idalie, the Folies and the Paphos)—those Bedlam: where the exuberance of idle youth is given free rein. Women who have exaggerated the fashion to the extent of perverting its charm and totally destroying its aims, are ostentatiously sweeping the floor with their trains and the fringes of their shawls; they come and go, pass and repass, opening an astonished eye like animals, giving an impression of total blindness, but missing nothing.

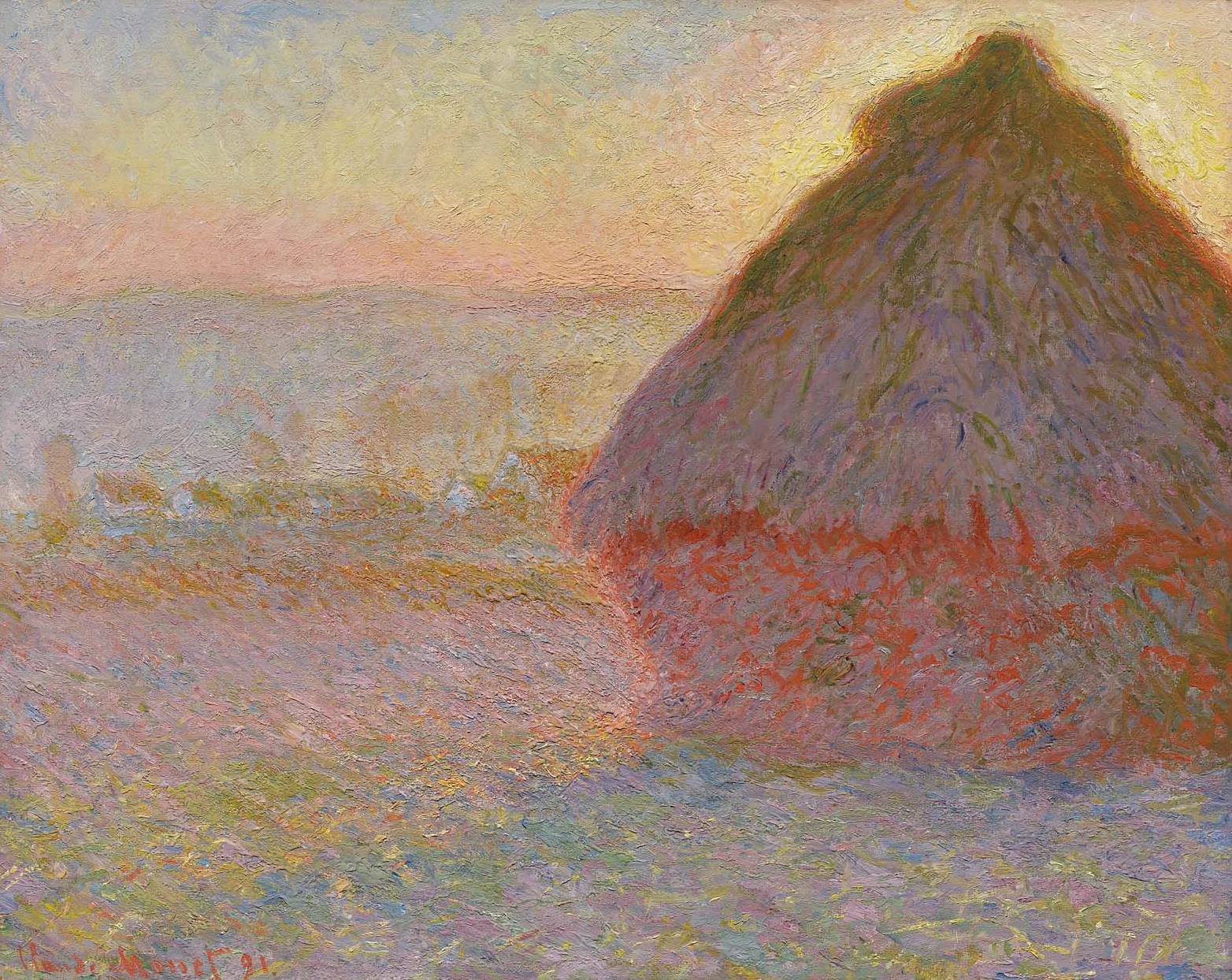

Against a background of hellish light, or if you prefer, an aurora borealis, red, orange, sulphur-yellow, pink (to express an idea of ecstasy amid frivolity), and sometimes purple (the favorite color of canonesses, like dying embers seen through a blue curtain)—against magical backgrounds such as dial, which remind one of variegated Bengal Lights, there arises the Proteam image of wanton beauty. Now she is majestic, now playful; now slender, even to the point of skinniness, now cyclopean; now tiny and sparkling, now heavy and monumental. She has discovered for herself a provocative and barbaric sort of elegance, or else she aspires, with more or less success, towards the simplicity which is customary in a it world. She advances towards us, glides, dances, or moves about with her burden of embroidered petticoats, which play the part at once of pedestal and balancing-rod; her eye flashes out from under her hat, Wet a portrait in its frame. She is a perfect image of the savagery that lurks the midst of civilization. She has her own sort of beauty, which comes to her from Evil always devoid of spirituality, but sometimes tinged with a weariness which imitates true melancholy. She directs her gaze at the horizon, like a bean of prey; the same wildness, the same lazy absent-mindedness, and also, at times, the same fixity of attention. She is a sort of gipsy wandering on the fringes of a regular society, and the triviality of her life, which is one of warfare and cunning. fatally grins through its envelope of show. The following words of that inimitable master, La Bruyire, may be justly applied to her: ‘Some women possess an artificial nobility which is associated with a movement of the eye, a tilt of the head, a manner of deportment, and which goes no further.”

These reflections concerning the courtesan are applicable within certain limits to the actress also; for she too is a creature of show, an object of public pleasure. Here however the conquest and the prize are of a nobler and more spiritual kind. With her it is a question of winning the heart of the public not only by means of sheer physical beauty, but also through talents of the rarest order. If in one aspect the actress is akin to the coy, in another she comes dose to the poet. We must never forget that quire apart from natural, and even artificial, beauty, each human being bears the distinctive stamp of his trade, a characteristic which can be translated into physical ugliness, but also into a sort of ‘professional’ beauty.

In that vast picture gallery which is life in London or Paris, we shall Dina with all the various types of fallen womanhood—of woman in revolt against society-at all levels. First we see the courtesan in her prime, striving after patrician airs, proud at once of her youth and the luxury into which she puts all her soul and all her genius, as she delicately uses two fingers to tuck in a wide panel of silk, satin or velvet which billows around her, or points a toe whose over-ornate shoe would be enough to betray her for what she is, if the somewhat unnecessary extravagance of her whole toilette had not done so already. Descending the scale, we come down to the poor slaves of those filthy stews which are often, however, decorated like cafes; hapless wretches, subject to the most extortionate restraint, possessing nothing of their own, nor even the eccentric finery which serves as spice and setting to their beauty.

Some of these, examples of an innocent and monstrous self-conceit, express in their faces sod their bold, uplifted glances an obvious joy at being alive (and indeed, one wonders why). Sometimes, quite by chance, they achieve poses of a daring nobility to enchant the most sensitive of sculptors, if the sculptors of today were sufficiently bold and imaginative to seize upon nobility wherever it was to be found, even in the mire; at other times they display themselves in hopeless attitudes of boredom, in bouts of tap-room apathy, almost masculine in their brazenness, killing time with cigarettes, orientally resigned—stretched out, sprawling on settees, their skirts hooped up in front and behind like a double fan, or else precariously balanced on stools and chairs; sluggish, glum, stupid, extravagant, their eyes glazed with brandy and their foreheads swelling with obstinate pride. We have climbed down to the last lap of the spiral, down to the femina simplex of the Roman satirist. And now, sketched against an atmospheric background in which both tobacco and alcohol have mingled their fumes, we see the emaciated flush of consumption or the rounded contours of obesity, that hideous health of the slothful. In a foggy, gilded chaos, whose very existence is unsuspected by the chaste and the poor, we assist at the Dervish dances of macabre nymphs and living dolls whose childish eyes betray a sinister glitter, while behind a bottle-laden counter there lolls in state an enormous Xanthippe whose head, wrapped in a dirty kerchief; casts upon the wall a satanically pointed shadow, thus reminding us that everything that is consecrated to Evil is condemned to wear horns.

Please do not think that it was in order to gratify the reader, any mote than to scandalize him, that I have spread before his eyes pictures such as these; in either-ate this would, have been to treat him with less than due respect. What inlet gives these works their value and, as it were, sanctifies them is the wealth of thoUghts to which they give rise, thoughts however which are generally solemn and dark. If by chance anyone should be so ill-advised as to seek here an opportunity of satisfying his unhealthy curiosity, I must in all charity warn him that he win find nothing whatever to stimulate the sickness of his imagination. He will find nothing bat the inevitable image of vice, the demon’s eye ambushed in the shadows or Messalina’s shoulder gleaming under the gas; nothing but pure art, by which I mean the special beauty of evil, the beautiful amid the horrible. In fact, if I may repeat myself in passing, the general feeling which emanates from all this chaos partakes more of gloom than of gaiety. It is their moral fecundity which gives these drawings their special beauty. They are heavy with suggestion, but cruel, harsh suggestion which my pen, accustomed though it is to grappling with the plastic arts, has perhaps interpreted only too inadequately.