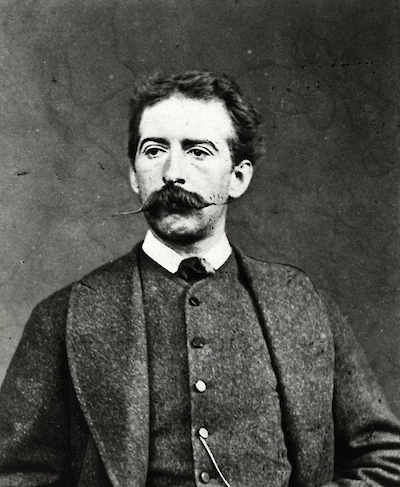

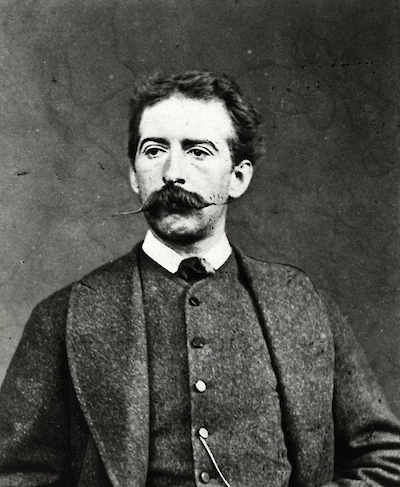

Winslow Homer

Transcend criticism by embracing solitude

Winslow Homer would hate this biography. When Boston art critic William Howe Downes contacted him for an interview, Homer replied, “It may seem ungrateful to you that after your twenty-five years of hard work in booming my pictures that I should not agree with you in regard to that proposed sketch of my life. But I think that it would probably kill me to have such a thing appear, and as the most interesting part of my life is of no concern to the public I must decline to give you any particulars in regard to it.”

Winslow Homer was a private man, and with good reason. His entrance to the art world came at a time when American art was struggling for international recognition, and after a meteoric rise to success, Homer was both lauded as a heroic American painter, and attacked by critics who expected him to define a new era of national art.

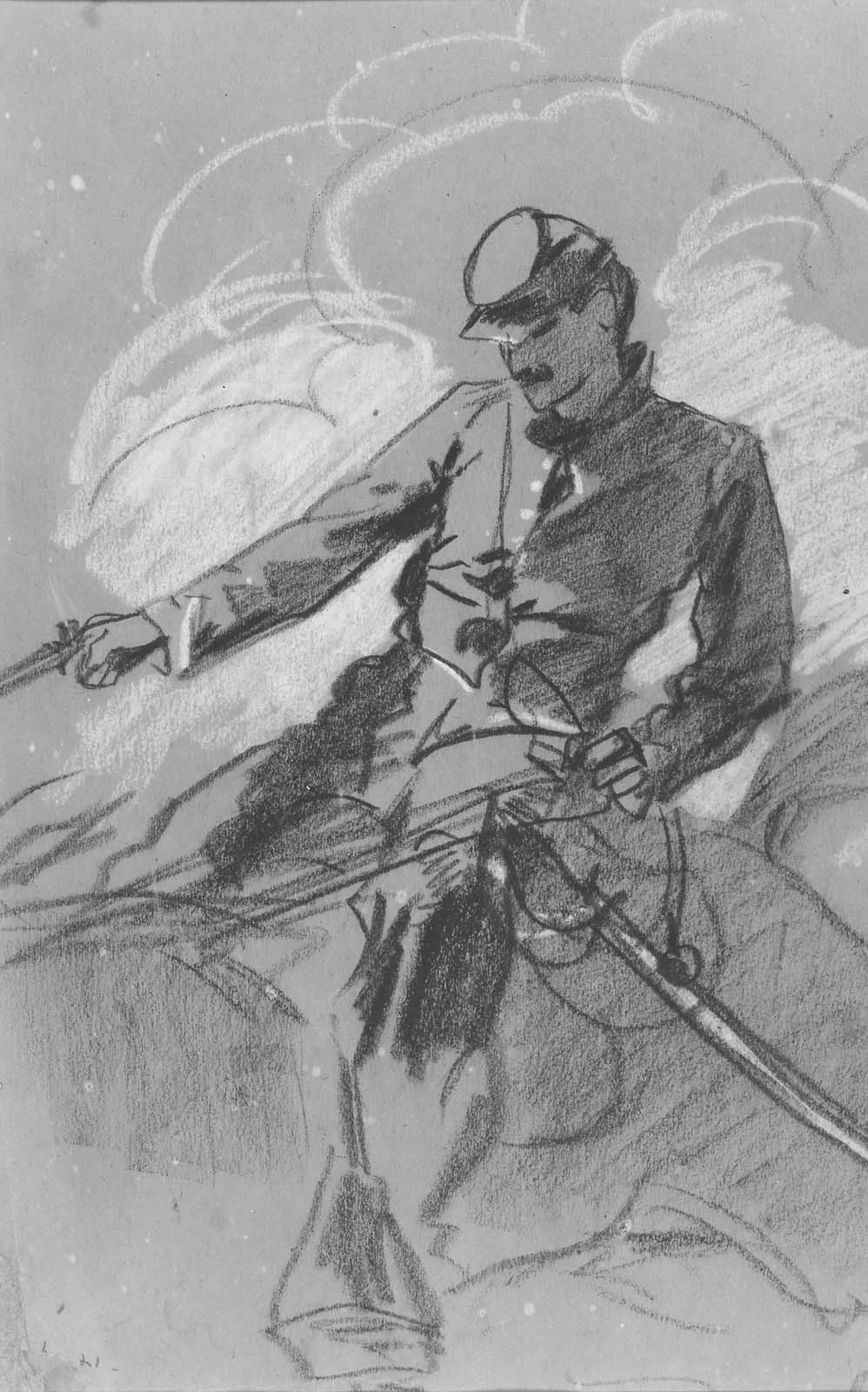

Despite his reticence, let’s talk about the artist’s life. Homer was born in Boston in 1836, and raised by his stoic mother after his father moved to Europe chasing a series of get-rich-quick schemes. Homer’s mother taught him to use watercolors, and imparted her dry wit and quiet nature. At 19, Homer was apprenticed to a lithographer, and developed a freelance illustration practice on the side. In 1861, Homer’s illustration commissions for Harpers magazine took him to the front lines of the American Civil War, and to his first taste of professional success. Back in his studio, Homer turned to oils to commemorate his experience on the front. His works Prisoners from the Front, and Home, Sweet Home, were shown at the National Academy of Design to critical acclaim. Winslow Homer was on his way to success.

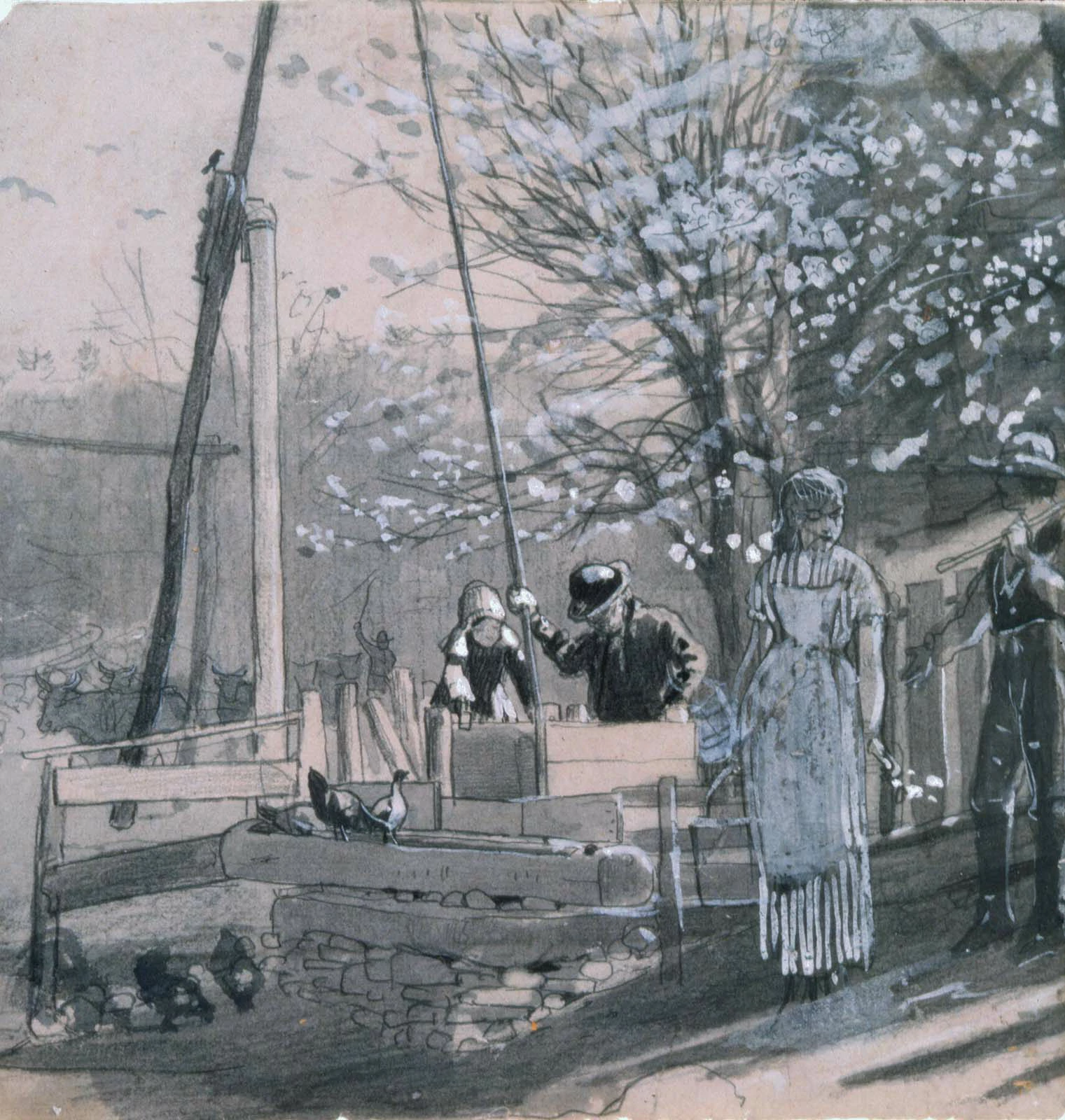

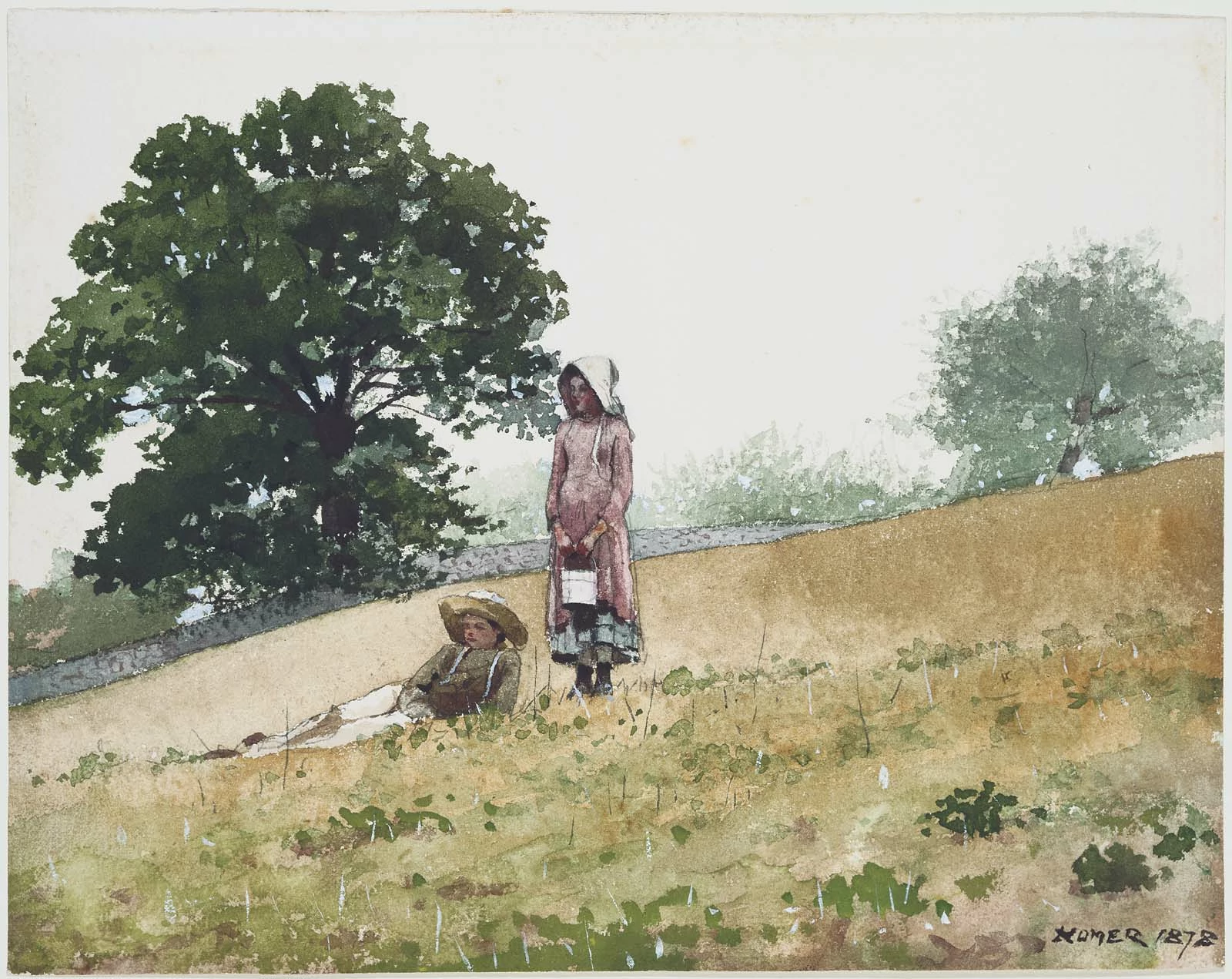

After the war, Homer continued his illustration for Harpers, while shifting his painting towards a more pastoral setting, and critics started leaning in. Homer’s name had become attached to American Art, and expectations mounted. His portrait of young women at a beach, Eagle Head, Manchester, Massachusetts, was called ‘trifling’ and of questionable taste. , and Rocky Coast and Gulls were called unfinished. Feeling the pressure to paint more ‘American’ subjects, Homer painted The Country School, which seemed to meet the critical expectation. Despite the volume of critical noise, paintings from Homer’s middle career show little evolution. Even a year in Paris saw little influence on his quiet, straightforward style. Homer avoided influence intentionally, to the extent that fellow painter Eugene Benson quoted him as saying “artists should never look at pictures, but should stutter in a language of their own.”

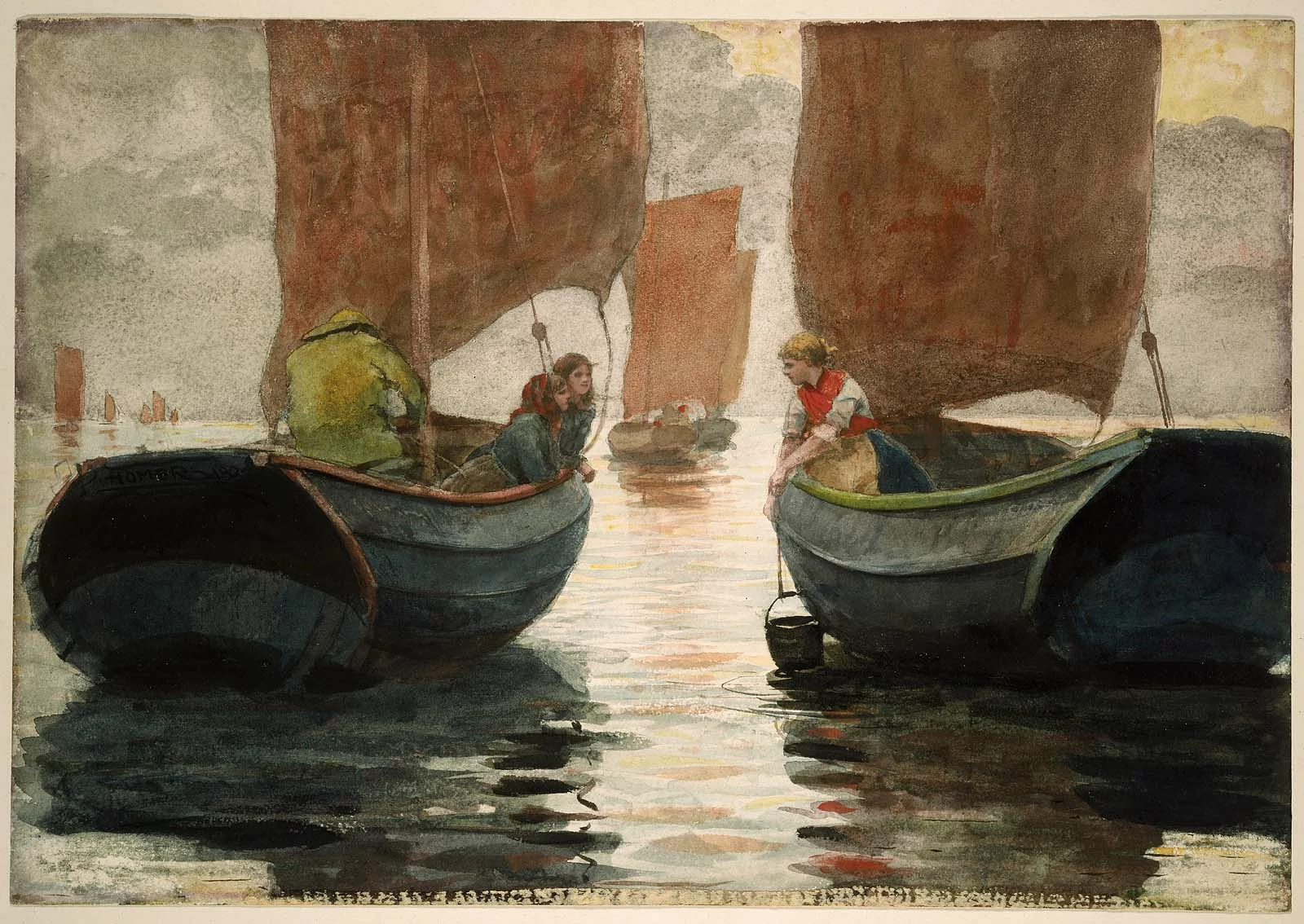

In the end, nature changed Homer’s work. In 1881, Homer turned 45 years old and moved to the English coastal town of Cullercoats. He worked in cold sober tones in watercolor. His subjects were the hardy souls who wrung a living from the sea. His pastoral scenes are replaced by struggle carried on broad shoulders, and the isolated dignity of survival. It was a radical change. Homer’s work had transcended nationalistic expectation, and on his return to America critics were swept away by his new work. “He is a very different Homer from the one we knew in days gone by, his pictures touch a far higher plane...They are works of High Art.”

Homer’s new muse was the sea, and he adopted a hermit’s life, living in Prouts Neck, Maine, in a carriage-house 75 feet from the ocean. He stayed by the ocean until his death in 1910, living frugally and painting hymns to the implacable power of nature. Homer had achieved what the art world expected of him—a quintessentially American voice—but only after finding the quiet courage of solitude.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Winslow Homer? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.