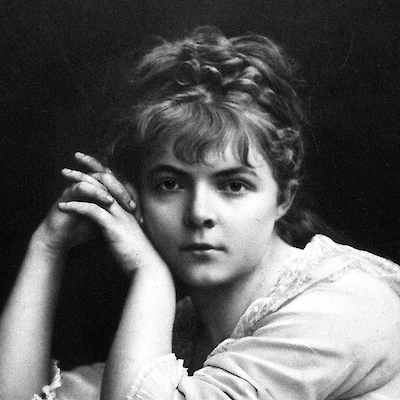

Marie Bashkirtseff

"To live so filled with ambition, and at the end, oblivion!"

1858 – 1884What use is there in posing and deceiving? Well, then, it is clear that I have the desire, if not the hope, to remain on the earth, through whatever means. (If I do not die in my youth, I hope to remain as a great artist; but if I die young, I wish my journal to be published, and it can not fail to interest. But, since I look for publicity, it may be asked, will not the idea that I am to be read, spoil, or rather destroy, the only merit such a book possesses? I answer frankly, no! In the first place, because I wrote for a long time without dreaming of readers, and for the rest, the very thought that I hope to be read, has made me absolutely sincere. If this book is not exact, absolute, strict truth, it has no reason for being. Not only do I always put'.down what I think, but I have never, for a single instant, dreamed of dissimulating anything which I thought might show me in a ridiculous or disadvantageous light. Besides, I find myself too admirable for censure! You may, therefore, be certain, indulgent readers, that I display myself in these pages at full length. I, as the subject of interest, may possibly appear slight to you; but forget that it is [ think only that it is a human being recounting to you all her impressions from childhood up. It will prove very interesting as a human document—Ask M. Zola, or M. de Goncourt, or Maupassant! ‘My journal begins in my twelfth year, but has no significance until I reach fifteen or sixteen. There remains, therefore, a gap to be filled, so I will write a sort of introduction, which will render comprehensible this monument of literature and human nature.

Suppose, first of all, that I am illustrious. Let us begin: I was born on the 11th of November, 1860. It is frightful merely to write it; but I console myself with the thought that when you read me, I shall certainly be no longer of any age at all.

My father was the son of Gen. Paul Grégorievitch Bashkirtseff, a provincial nobleman, brave, stubborn, unyielding-— even fierce. My grandfather was raised to the rank of general after the Crimean war, I believe. He married a young girl, the adopted daughter of a very great nobleman. She died at the age of thirty-eight, leaving five children—my father and four sisters.

Mamma was-married at twenty-one, after having refused several very good offers. She was a Babanine. On the side of the Babanines we are of ancient provincial nobility, and grandpapa always prided himself on being of Tartar descent, dating from the first invasion. Baba and Nina are Tartar words — to me it is all nonsense. Grandpapa was a contemporary of Lermontoff, Poushkine, etc. He was a Byronian, a poet, soldier, and scholar. He had been to the Caucasus. At a very early age he married Mademoiselle Julie Cornelius, aged fifteen, a very gentle and pretty girl. They had nine children—you will make allowances for the smallness of the number!

After two years of marriage, mamma took her, two children and went to live with her parents. I lived almost always with grandmamma, who idolized me. Besides grandmamma, I had also my aunt to adore me, whenever mamma did not carry her off. She was younger than mamma, but not pretty, sacrificed by everyone, and always sacrificing herself.

In May, 1870, we went abroad, and mamma’s long-cherished dream was realized. We remained a month at Vienna, intoxicated by the novelty of everything, the beautiful stores and theatres. We reached Baden-Baden in June, at the height of the season, in the midst of its Parisian luxury. The party comprised grandpapa, mamma, Aunt Romanoff, Dina (my first cousin), Paul, and me, and we had with us a doctor — the angelic, the incomparable Lucien Walitzky. He was a Pole, free from extravagant patriotism, of kindly disposition, and winning manners, and spent his entire income on his profession. At Achtirka he was district physician. He had been a classmate of mamma’s brother, at the University, and was always regarded as one of the family. At the moment of our going abroad, a physician was needed for grandpapa, and Walitzky was taken along. At Baden I‘ made my acquaintance with society and high life, and there I was I first troubled with vanity.

But I have not said enough about Russia and myself, which are the important topics. After the usual custom of the families of noblemen living in the country, I had two instructresses, one Russian and the other French; The first (Russian) of whom I have any recollection, was a certain Madame Melnikoff, a well informed woman of the world, of a romantic disposition, and separated from her husband. She had made herself a teacher, on a sudden impulse, after the reading of numerous romances. She was regarded as a friend by the entire household, and all treated her as an equal. All the men paid her court, and one fine morning, after some romantic episode or other, she eloped. The Russians are very romantic. She might just as well have bidden us good-bye and gone away naturally. My simple minded and theatrical family fancied that her departure would make me ill. During the entire day they, watched me with pitying looks and I believe that grandmamma even made me a special soup of the kind given to sick persons. I felt myself growing pale under such an exhibition of sensibility. I was, for the rest, thin, fragile, not at all pretty; but all that did not prevent everybody from looking upon me as a creature that would inevitably, absolutely, some day, attain the pinnacle of beauty, brilliancy, and splendor. Mamma once visited a Jew who told her fortune as follows: “You have two children,” said he; “the son will be like anyone else, but the daughter will be a star!”

One evening, at the theatre, a gentleman said to me, laughingly:

“Show me your hands, Mademoiselle. Ah! from the style in which she is gloved, there is no doubt that she will be a terrible coquette.”

I was very proud of this for a long time. Since I began to think, since I was three years old (I was not weaned until I was three and a half), I have had longings after indescribable grandeurs. My dolls were always queens or kings; all my thoughts, all the conversations of those surrounding my mother seemed always to refer to these grandeurs inevitably approaching.

When I was five, I dressed myself up in mamma’s laces, with flowers in my hair, and went in the drawing-room to dance; I was the famous danseuse, Pepita, and everyone came in to see me. Paul was almost nobody, and Dina, though the daughter of the beloved Georges, did not put me in the shade; Still another incident: When Dina was born, grandmamma went and took her unceremoniously from her mother, and kept her ever after. That was before I was born.

After Madame Melnikoff, I had for governess, Mademoiselle Sophie Dolgikoff, who was only sixteen — Holy Russia!! — and another, a French woman, called Madame Brenne, who got herself up in the style of the Restoration, and had an air of extreme sadness, with her pale blue eyes, her fifty years, and her consumption. I liked her very much. She taught me drawing; and, under her instruction, I made an outline draw ing of a little church. I drew a great deal, and while the grown folks had their card parties, I amused myself by drawing on the card-table.

Madame Brenne died in the Crimea, in 1868. The little Russian, treated like a child of the house, was on the eve of marrying a young man whom the doctor had brought home with him, and who was known for his numerous matrimonial checkmates. This time everything seemed progressing swimmingly, when, going into her room one evening, I found Mademoiselle Sophie, with her nose buried in her pillow, weeping desperately. Everyone hurried to the room.

“What is the matter?”

At last, after many tears and sobs, the poor child managed to say that she could never, never! Then more tears.

“But why?”

“Because—because I can not get used to the sight of him!”

The fiancé heard everything from the drawing-room. An hour later he strapped up his trunk, sprinkling it with his tears, and left. It was his seventeenth matrimonial failure.

I recall distinctly, her exclamation: “I can not get used to the sight of him!” It came so frankly from the heart, and I understood very clearly, even then, how truly horrible it would be to marry a man to whose appearance one could not grow accustomed.

This brings us back to Baden, in 1870. When the war was declared, we marched upon Geneva; I with my heart full of bitterness and projects of revenge. Every night before going to bed, I whispered this supplementary prayer:

“ Oh, God, grant that I may never have the small-pox, that I may be beautiful, that I may have a fine voice, that I may be happy in my domestic affairs, and that mamma may live a long time!”

In Geneva, we staid at the Hotel de la Couronne, on the shore of the lake. I had a drawing teacher, who brought me set designs to copy; little chalets in which the windows were drawn to look like trunks of trees, and not at all like real windows of real chalets. So I refused to draw them, not comprehending how a window could be, made like that. Then the good man told me to draw the window as it looked, frankly after nature. By this time, we had left the Hotel de la Couronne, and were living at a family boarding-house, where Mont Blanc directly faced us. I copied scrupulously, therefore, whatever I saw in Geneva and the lake, and that was the end of it, I have forgotten just why. At Baden, there had been time to have our portraits made after photo graphs, and the portraits appeared to me overdone and ugly, from the efforts to have them look pretty.

When I am dead, people will read my life, which I myself find very remarkable. (Had it been entirely different I should probably think the same!) But I hate prefaces (they have deterred me from reading many an excellent book) and publishers’ notices. This is the reason why I wished to write my own preface. I might have omitted it, had I published the entire book; but I limit myself to beginning at my twelfth year, what precedes, being too diffuse. Moreover, in the course of the journal, I give you sufficient glimpses of, and return frequently to my recollections of the past, apropos of anything or nothing.

What if I should die suddenly, carried away by some swift disease? Probably I should not know that I was in danger; they would conceal it from me, and after my death they would search among my papers; my journal would be found, and after reading it, my family would destroy it, and in a short time, of me there would remain nothing—nothing—nothing! This is the thought that has always terrified me; to live, to be so filled with ambition, to suffer, to weep, to struggle, and, at the end, oblivion! oblivion! as if I had never existed. If I should not live long enough to win renown, this journal will interest the psychologists; for it is curious, at least — the life of a woman, traced day by day, without affectation, as if no one in the world should ever read it, and yet at the same time intended to be read; for I am convinced that I shall be found sympathetic — and I tell everything, everything, everything, Otherwise what use were it? Well it will be very evident that I tell everything.

Paris, May 1, 1884.