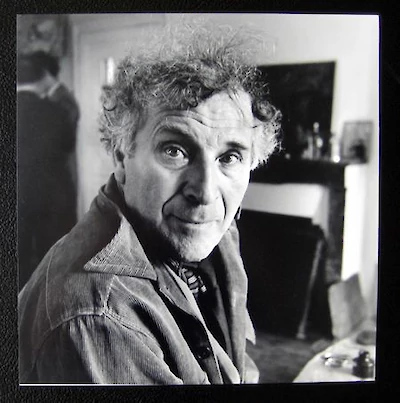

Marc Chagall

A painter of inner and outer worlds

1887 – 1985The first thing I ever saw was a trough. Simple, square, half hollow, half oval. A market trough. Once inside, I filled it completely. I don't remember -- perhaps my mother told me -- but at the very moment I was born agreat fire broke out, in a little cottage, behind a prison, near the highroad, on the outskirts of Vitebsk. The town was on fire, the quarter where the poor Jews lived. They carried the bed and the mattress, the mother and the babe at her feet, to a safe place at the other end of town.

But, first of all, I was born dead.

I did not want to live. Imagine a white bubble that does not want to live. As if it had beenstuffed with Chagall pictures. They pricked that bubble with needles, they plunged it into a pail of water. At last itemitted a feeble whimper.

But the main thing was, I was born dead.

I hope the psychologists have the grace not to draw improper conclusions from that! However, that little house near the Pestkowatik road had not been touched. I saw it not so long ago. As soon as he was a little better off, my father sold the cottage. The place reminds me ofthe bump on the head of the rabbi in green I painted, or of a potato tossed into a barrel ofherring and soaked in pickling brine. Looking at this cottage from the height of my recent"grandeur,” I winced and I asked myself: “How could I possibly have been born here? How does one breathe?”

However, when my grandfather, with the long, black beard, died in all honor, my father, for a few roubles, bought another place. In that neighborhood, no longer near an insane asylum as at Pestkowatik. All about us, churches, fences, shops, synagogues -- simple and eternal, like the buildings in the frescoes of Giotto. Around me come and go, turn and turn, or just trot along, all sorts of Jews, old and young, Javitches and Bejlines. A beggar runs towards his house, a rich man goes home. The cheder boy runs home. Papa goes home.

In those days there was no cinema. People went home or to the shop. That is what I remember after my trough. I say nothing of the sky, of the stars of my childhood. They are my stars, my sweet stars; they accompany me to school and wait for me on the street till I return. Poor dears, forgive me. I have left you alone on such a dizzy height! My town, sad and gay!

As a boy, I used to watch you from our doorstep, childishly. To a child’s eyes you were clear. When the walls cut off my view, I climbed up on a little post. If then I still could not see you, I climbed up on the roof. Why not? My grandfather used to climb up there too. And I gazed at you as much as I pleased.

Here, in Pokrowskaja Street, I was born a second time.

Have you sometimes seen, in Florentine paintings, one of those men whose beard is never trimmed, with eyes at once brown and ash-gray, with the complexion the color of burnt-ochre and all lines and wrinkles? That is my father. Or perhaps you have seen one of the figures in the Haggadah, with their sheep like expressions (Forgive me, dear father!). You remember I made a study of you. Your portrait was to have had the effect of a candlethat bursts into flame and goes out at the same moment. Its aroma—that of sleep.

A fly buzzing around—curse it!—and because of it I fall asleep.

Must I talk about my father? What is a man worth if he is worth nothing? If he is priceless? That is why it is difficult forme to find the right words for him. My grandfather, a teacher of religion, could think of nothing better than to place my father—his first-born son—still in childhood, as a clerk in a herring plant, and hisyoungest son with a hairdresser. No, my father was not a clerk but, for thirty-two years, simply a laborer. He lifted heavy barrels and my heart used to twist like a Turkish bagel as I watched himlift those weights and stir the herring with his frozen hands. His huge boss would stand toone side like a stuffed animal. My father’s clothes sometimes shone with herring brine. Farther off, light from abovewould fall into reflections on every side. Alone, his face, now yellow, now white, wouldfaintly smile from time to time.

What a smile! Where did it come from?

It whispered of the street where dim passers-by roamed about, reflecting the moonlight, Suddenly, I saw his teeth shine. They made me think of a cat’s teeth, of a cow’s teeth, ofany teeth. Everything about my father seemed to me enigma and sadness. An image inaccessible. Always tired, always pensive, his eyes alone gave forth a soft reflection of a grayish-blue. In his greasy, work-soiled clothes, a handkerchief of dull red showing at one of the bigpockets, he would come home, tall and thin. The evening came in with him. From his pocket he would draw a pile of cakes, of frozen pears. With his brown andwrinkled hand he'd pass them out to us children. They were more delicious, more savoryand more ethereal than if they had come from the dish on the table. And an evening without cakes and without pears from Papa’s pockets was a sad evening for us.

I was the only one who really knew him, that simple heart, poetic and muted.

He earned, right up to the last expensive years, a modest twenty roubles or so. The smalltips from buyers were scarcely enough to increase his budget. And yet my father had notbeen a poor young man. The photograph of him in his youth and my own observations of our wardrobe proved tome that when he married my mother he had a certain physical and financial authority; forhe presented his fiancée—a little girl who grew after her marriage—with a magnificent shawl.

Once married, he gave up turning over his wages to his father and supported his ownhousehold. But first I'd like to finish the silhouette of my bearded grandfather. I don't know how longhe continued to teach. He was said to be a much-respected man. Ten years ago, when I went to the cemetery with my grandmother to visit his grave andsaw his monument, I was convinced that he was a good man. An inestimable man, a saint. He lies close by the river near the dark fence where the troubled waters flow. Below thehill, near other saints long dead. Though well worn, his gravestone, with the letters in Hebrew: “Here lies . . . ,” is still intact. My grandmother pointed to it.

“There is the grave of your grandfather, the father of your father and my first husband.”

Her lips quivered, but she couldn't cry. She whispered a few words, her own or prayers. Iheard her wailing as she bent over the monument, as though that stone and that littlemound of earth were my grandfather, as though she were speaking to the bowels of theearth or as though the grave were a kind of cupboard with something shut away forever in it. “I beseech you, David, pray for us. This is your Bachewa. Pray for your sick son, Chaty, for your weak Zussy, for their children. Pray that they may be upright, honest men before God and man.” On the other hand, I felt closer to my grandmother. All there was to that little old woman was a scarf around her head, a little skirt and a wrinkled face. She was tiny.

In her heart, a love devoted to her few favorite children and to her book of prayers. As a widow she married, with the approval of the rabbi, my other grandfather, mymother’s father, himself a widower. My mother’s mother and my father’s father had died the year my parents married. My mother had ascended the throne.