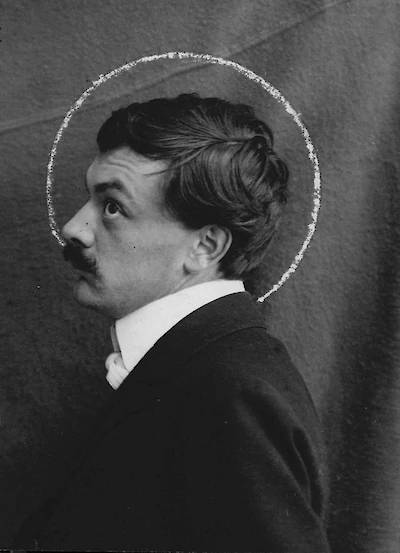

Koloman Moser

Wallpaper to postage stamps, Kolo does it all

What would the world look like if everything was special? If all the things that are mass produced for innocuous consumption were reimagined with the creativity and craft of the world’s greatest artists? This was Koloman Moser’s vision, and in fifty short years he made it real, transforming what it meant to make at the dawn of the 20th century.

Like many of the great figures who emerge from convulsive shifts in the art world, Moser was in the right place at the right time. Born in 1868 and raised in Vienna during a decades-long period of artistic conservatism, Moser balanced painting studies at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts with commercial illustration to support his family after his father’s death in 1888. Moser not only balanced these disciplines but thrived, an early hint that Koloman was a powerhouse. But creative engines need something to spin, and Moser found his focal point in Vienna’s cafes and bars, where the city’s young artists were hatching a plan.

Let’s back up. Vienna was one of two capital cities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a bastion of conservative politics and culture while the rest of Europe exploded with industrialization. Similar to the near total dominance of the Paris Salon, Vienna’s art world was held in a stranglehold by the Association of Austrian Artists and the single municipal venue for exhibition, the Kunstlerhaus. Together they controlled public commissions in a monopoly critic Hermann Bahr described as “peddlers who pass for artists and have a commercial interest that prevents art from flourishing.”

But outside the establishment, young artists were agitating for a new kind of art production, a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total practice, unifying high art with craft. This was the wave that Moser was poised to ride, but with such energy he lifted tectonic plates and pushed the wave forward himself.

On April 3rd, 1897 Moser was one of 40 artists and architects who delivered a letter to the Association of Austrian Artists declaring the foundation of a new group, the Vienna Secession. They aimed to reconnect Vienna’s closed, nationalistic art scene to the global art world, bring art out of public buildings and back into people’s homes, and rebirth the mundane world into shimmering aesthetic perfection. It was a mission Moser tackled with unblinking sincerity.

A year after the succession Moser applied his artistic eye to product design, releasing his first collection of decor, including hand knotted rugs and cushion covers. Three years later he expanded his practice, turning his home into an all-encompassing experiment with interior design that was undocumented, but impressive, as it earned him the patronage of the absurdly wealthy and forward thinking cotton baron Fritz Waerndorfer.

With Waerndorfer’s financial backing, Moser constructed possibly his greatest contribution to the aesthetic world in 1903, partnering with architect Josef Hoffmann to found an extraordinarily ambitious multidisciplinary design studio. The Wiener Werkstätte, or Viennese Workshops, was a product development and manufacturing company that brought together artists, architects, ceramicists, bookbinders, jewelers, wood, metal and leather workers and graphic artists to redesign nearly every conceivable facet of modern life, from furniture to fashion, interior design to architecture. Within the Werkstätte Moser’s creative output exploded into a portfolio of patterned, expressive interpretations of modern necessities. Moser designed lamps, wallpaper, furniture, and a huge diversity of decor.

The scope of Moser’s work was remarkable, and quickly evolved into a recognizable style blending the clean lines of Romanesque classicism with dense geometric patterning and decorative design that presaged art nouveau and Art Deco. The publisher Alexander Koch described Moser’s insatiable creativity, saying “Of the artists who founded the Vienna Secession, Kolo Moser was unabashedly the boldest and one of those who caused Viennese philistines the most trouble in the early days of the Secession. Wherever there was something to reform in Viennese arts and crafts – and where wasn’t that needed? – you could find Kolo Moser working away with persistence intrepidness, taste, and astounding technical skill.”

But the Gesamtkunstwerk ambitions of the studio relied on private buyers with deep deep pocketbooks, and when commissions failed to cover the studio’s expenses, stakeholders approached the industrial heiress Editha Mautner von Markhof for a loan. The situation was sticky, since Moser had married Editha a year before, and the financial stress and the studio’s refusal to adopt Moser’s recommended structural changes led to a rift between the founders. Four years after its founding Moser left the Werkstätte. With the practical realities of total artwork shaken, Moser returned to more traditional art-making in 1907. Moser dedicated his next decade to painting, exploring the symbolist styles he'd been entranced by in his youth. By 1916, he'd been diagnosed with cancer of the larynx, a final struggle that finally claimed him two years later at the age of 50.

Koloman Moser’s own life was a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, an explosive, all-encompassing creative outpouring rooted in a nearly impossible ideal. And it showcases a sly benefit of applying art to mundane objects. While most great artwork lives in galleries or the private collections of the ultra-wealthy, you can still buy reissues of many of the products Moser designed on marketplaces like 1stdibs and Chairish. The Succession, it seems, lives on.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Koloman Moser? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.