Johannes Vermeer

Can you cheat at art?

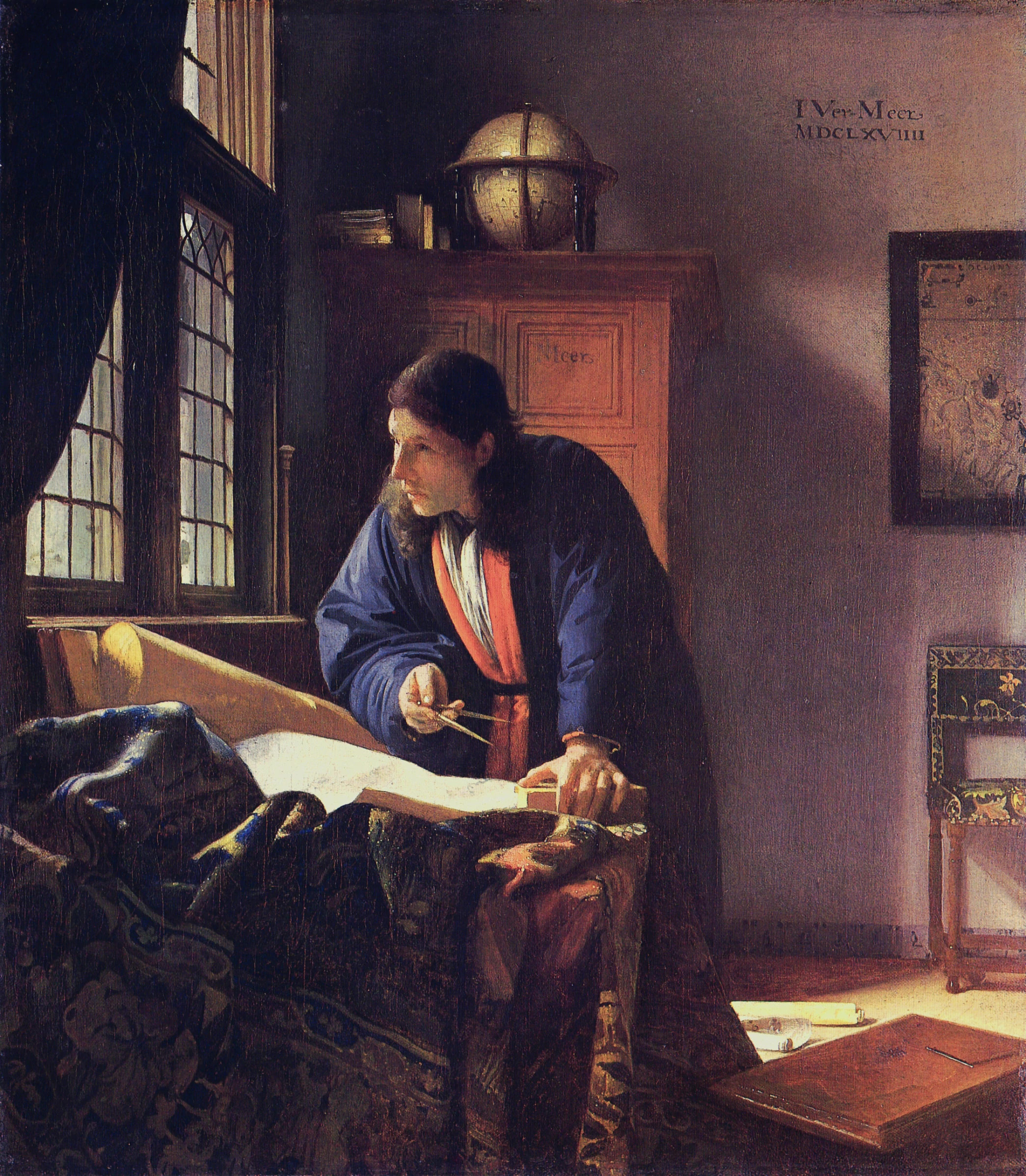

Johannes Vermeer was a perfectionist. He painted slowly and with expensive pigments. He made only 34 paintings, most of them quiet, eerily realistic domestic scenes. Vermeer was mildly successful in his day, but his death left his family impoverished, and for the next two centuries his work was attributed to more well known artists. Today, Vermeer is among the most popular and obsessively researched artists in history. His work is scrutinized around the world and analyzed by scholars and scientists. So what happened? What’s the big deal with Vermeer?

Obviously, Vermeer made outstandingly beautiful paintings of subtlety and depth. His work shows a sensitivity to face and attitude, and his work is discussed at length by critics the world over. But it was controversy that brought his work back to life.

The first controversy was the rediscovery of Vermeer’s work itself. For 200 years many of his paintings had been attributed to more popular artists, like Gabriël Metsu or Frans van Mieris (who are now all but forgotted, ironically). In 1860, the German Museum director Gustav Waagen recognized The Art of Painting as a Vermeer, and during the next few years the French art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger went on a rampage of rediscovery, attributing over 70 works to Vermeer. Many of these attributions have since been disproven, but every claim brought Vermeer further into the public eye. Everyone loves drama.

The struggle for attribution took a dark tone in 1945 when nearly all of Vermeer’s supposed religious paintings were tracked back to the soon legendary forger Han van Meergeren. Meergeren’s invented Vermeer’s Christ with the Adulteress whichhad sold a few years earlier to Hermann Göring for 1.65 million guilders, approximately 7 million USD today. Practically overnight Vermeer’s oeuvre shrank dramatically, with The Head of Christ, The Last Supper II, The Blessing of Jacob, The Adulteress, and The Washing of the Feet identified as fakes. And the trouble was just getting started.

In 2001, David Hockney proposed a radical theory explaining Vermeer’s nearly photo-realistic work. His book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, claimed that Vermeer, along with other renaissance artists used a camera obscura, and camera lucida to project the subjects of their paintings onto their canvases, allowing them to reproduce reality with a previously impossible precision.

It’s a fascinating theory, and while there’s no historical proof that Vermeer used optical technology to trace his work from life, it absolutely blew up the art world. Historian James Elkins denied Hockney’s claim, saying the camera obscura technique was “radically undertested.” The Washington Post’s art critic Blake Gopnik claimed Hockey’s theory was fraught with “technical ignorance, philosophical incoherence and logical inconsistency,” and essayist Susan Sontag expressed a common attitude of dismay that the ‘great masters’ would stoop to using technology to support their work. “If David Hockney’s thesis is correct, it would be a bit like finding out that all the great lovers of history have been using Viagra.”

The controversy heightened in 2013, when noted illusionists Penn and Teller released a documentary about the Texan inventor Tim Jenison, who constructed a camera lucida and reproduced Vermeer’s with debated success. The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones called the project ‘depressing’ and ‘crass’ but one thing can’t be argued. People are still talking about Vermeer.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Johannes Vermeer? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.