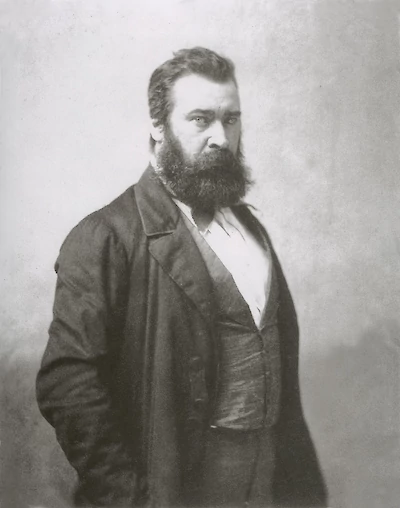

Jean-François Millet

A peasant I was born, and a peasant I will die

1814 – 1875[Editor’s note: Jean-François Millet was raised in the poor farming community of Gruchy, in the Gréville-Hague commune of northern France. Millet dedicated much of his work to capturing the lives of the peasent-folk he grew up with. In his memories of his childhood, you can see a great warmth and appreciation for the simple work and generous nature of his childhood community. Millet wrote down these memories for his friend Alfred Sensier, who would publish a partial biography of the artist in 1881, six years after his death.]

I remember being awakened one morning by voices in the room where I slept. There was a whizzing sound which made itself heard between the voices now and then. It was the sound of spinning-wheels, and the voices were those of women spinning and carding wool. The dust of the room danced in a ray of sunshine which shone through the high narrow window that lighted the room. I often saw the sunshine produce the same effect again, as the house faced east. In one corner of the room there was a large bed, covered by a counterpane with broad red and brown stripes, which hung down to the floor. There was also a large brown cupboard against the wall, between the feet of the bed and the window. All this comes back to me as in a vague, a very vague, dream. If I were asked to recall in the faintest degree the faces of those poor spinners, all my efforts would be in vain, for although I grew up before they died, I only remember their names because I heard them afterwards spoken of in my family. One of them was my old great-aunt Jeanne. The other was a spinner by profession, who often came to the house, and was called Colombe Gamache.

This is the oldest of all my memories. I must have been very little when I received that impression, and it was a long time before I became conscious of any more distinct images. I only remember confused impressions, such as the sound of steps coming and going in the house, the cackle of geese in the yard, the crowing of the cock, the swing of the flail in the barn, and similar noises which fell on my ears constantly and produced no particular emotion.

There is a little fact which stands out more clearly. The Commune invested in some new bells: two of the old ones had been melted down to make guns, and the third had been broken, as I heard afterwards. My mother had the curiosity to go and see the new bells, which were placed in the church to be baptized before they were hung in the tower, and took me with her. She was accompanied by a girl named Julie Lecacheux, whom I knew very well afterwards. I remember how much I was impressed at finding myself in so vast a place as the church, which seemed even more immense than our barn, and how the beauty of the big windows with their lozenge-shaped panes struck my imagination. We saw the bells, all three resting on the ground, and they also appeared enormous, since they were much bigger than I was ; and then (what no doubt fixed the scene in my mind) Julie Lecacheux, who held a very big key in her hand — probably that of the church — began to strike the largest bell, which rang loudly, filling me with wonder and admiration. I have never forgotten the sound of that key on the bell.

I had an old great-uncle who was a priest. He was very fond of me, and took me about everywhere with him. Once he took me to a house where he often went. The lady of the house was aged, and lives in my mind as the type of a lady of the old regime. She caressed me, gave me a slice of bread and honey, and into the bargain a fine peacock’s feather. I remember how good that honey tasted, and how beautiful the feather seemed! I had already been filled with wonder on entering the yard at the sight of two peacocks perched on a big tree, and I could not forget the fine eyes on their long tails!

My great-uncle sometimes took me to Eculleville, a little hamlet of Greville. The house to which he took me was a sort of chateau, known as the mansion of Eculleville. There was a maid named Fanchon. The owner, whom I never knew, had a taste for rare trees, and had planted some pines. You would have to go a long way in our neighborhood before you could find so many together. Fanchon sometimes gave me some pine-cones, which filled me with delight.

This poor great-uncle was so afraid of any harm happening to me that he was miserable if I was not at his side. This I had been often told; but as I by this time was able to run, on one occasion I escaped with some other boys, and climbed down the rocks to the sea-shore. After trying in vain to find me, he ended by coming down to the sea, and caught sight of me bending over the pools left by the retreating tide, trying to catch tadpoles. He called me in so terrified a voice, that I jumped up without delay, and saw him on the top of the cliffs beckoning to me to return at once. I did not let him call twice, for his look frightened me; and if I could have found any other way than the path at the top of which he was awaiting me, I would have taken it. But the steepness of the cliff forced me to take this path. When I had reached the top, and was out of danger, he flew into a violent rage. He took up his three-cornered hat and began to strike me with it; and as the cliff was still very steep on the way back to the village, and my little legs could not carry me very fast, he followed me, beating me, with a face as red as a turkey-cock. So he pursued me all the way to the house, saying with each blow of his hat,’ There! I will help you to get home!’ This filled me with great dread of the three-cornered hat. My poor uncle on his part had the most frightful nightmare all the following night, and kept waking up every minute in terror, crying out that I was falling over the cliff. Since I was not old enough to appreciate a tenderness which took the form of blows, this was by no means the only alarm which I gave him. It appears that once during mass I chattered with some other children. He coughed, as a sign to stop me, but I soon began again. Then he came down the church, and taking me by the arm, made me kneel down under the lamp in the middle of the choir. I do not know how it happened, for I never in all my life had the least wish to resist punishment, but somehow I caught my foot in his surplice and tore it. Overwhelmed with horror at this act of impiety, he left me without giving me the intended penance, and returned to his place, where he remained, more dead than alive, until the end of mass. I had no notion what a crime I had committed, and was very much surprised when, on our return from mass, my great-uncle began with emotion to tell the whole family what an abominable outrage I had committed on his person — an act, in fact, little short of sacrilege. Such a crime, committed against a priest, made him prophesy fearful things of my future. It would be impossible to paint the consternation of the whole family. For my part, I could not understand why I had suddenly become an object of horror, and my dismay was great. There, however, my recollections of this unhappy affair end.

Time has dropped his veil over that, as over other things, and I cannot remember if I was ever further punished.

This I remember hearing about my great-uncle, who was the brother of my paternal grandfather. He had been a laborer in his youth, and had become a priest rather late in life. I think he had a small parish at the time of the Revolution. I know that he was persecuted at that time, and I have heard how a party of men came to search my grandfather’s house, when he was hidden there. They prosecuted their search in the most brutal fashion ; but being of an ingenious turn of mind, he managed to make a hiding-place which communicated with his bed, where he took refuge when his enemies came. One day they arrived so unexpectedly that his bed had not yet had time to get cold, and when they were told that he was gone, they exclaimed, ‘ He was here just now ; the bed is still warm, but he has managed to escape ! ‘ And all the while he could hear them talking. In their fury they turned the whole house upside down, and then went away.

My uncle said mass, when he could, in the house; and I have still the leaden chalice which he used. After the Revolution he lived on with his brother, and held the office of Vicar of the parish. Every morning he went to church to say mass; after breakfast he went to work in the fields, and almost always took me with him. When we reached the field, he took off his cassock, and set to work in shirt-sleeves and breeches. He had the strength of Hercules. Some great walls which he built to support a piece of sloping ground are still standing, and are likely to last for many years to come. These walls are very high, and are built of immense stones. They give one an impression of Cyclopean strength. I have heard both my grandmother and father say that he would allow no one to help him to lift even the heaviest stones, and there are some which would require the united strength of five or six ordinary men with levers to move them.

He had an excellent heart. He taught the poor children of the village, whose parents could not send them to school, for the love of God. He even gave them simple Latin lessons. This excited the jealousy of his fellow-priests, who complained of him to the Bishop of Coutances. I once found, among some old papers, a rough draft of a letter which he addressed in self-defense to the bishop, saying that he lived at home with his peasant brother, and that in the Commune there were some poor children who had no sort of instruction. He had therefore decided to teach them as much as he could, out of pity, and begged the bishop, for the love of God, not to prevent these poor children from learning to read. I believe the bishop at length consented to let him have his own way — a truly generous permission!

As he grew old my great-uncle became very heavy, and often walked faster than he wished. I remember how often he used to say, ‘Ah! the head bears away the limbs.’ At his death I was about seven years old. It is very curious to recall these early impressions, and to see how ineffaceable is the mark which they leave upon the mind.

My childhood was cradled with tales of ghosts and weird stories, which impressed me profoundly. Even to-day I take interest in all those kind of subjects. Do I believe in them or not? I hardly know. On the day of my great-uncle’s funeral I heard them speaking in mysterious terms of his burial. They said that ‘some heavy stones, covered with bundles of hay, must be placed at the head of the coffin, for that would give the robbers trouble. Their tools would get caught in the hay, and would break on the stones, so that it would be impossible to hook up the head, and pull the body out of the grave.’ I afterwards learnt the meaning of this mysterious language. From the day of the funeral several friends, and the servant of the house, who were given hot cider to drink, spent each night, armed with guns and any other weapons they could find, keeping watch at the grave where my great-uncle had been buried. This guard was kept up for about a month. After that, they said, there was no more danger. The meaning of all these precautions was, that there were men about who made a profession of digging up dead bodies for the use of doctors. Whenever any one died in the Commune, they would come at night to steal the body. Their practice was to take a long screw, and, working through the ground and the lid of the coffin, hook up the head of the dead man, and so draw out the body without disturbing the earth on the surface. They had been met leading the corpse covered over with a mantle, supporting it in their arms, and speaking to him as if he were a drunken man, telling him to stand up. At other times they have been seen on horseback, carrying the dead man in the saddle, with the arms tied round the rider’s waist, and always covered up with a great cloak, but often the feet of the corpse could be seen below. Some months before the death of my great-uncle I had been sent to school, and I remember well that on the day he died, the maidservant was sent to bring me home, lest at so solemn a moment I should be seen playing on the road. Before I went to school I had begun to learn my letters, and, perhaps, to spell, for the other children thought me already very clever. God knows what they called clever!

My first arrival at school was for the afternoon class. When I reached the court, where the children were at play outside, the first thing that I did was to fight. The bigger children, to whose care I had been trusted, were proud of bringing a child to school who was only six and a half, but who already knew his letters; and I was so big and strong, that they assured me there was not one boy of my age, or even of seven, who could beat me. There were no other children there under seven; they were determined to prove the truth of this assertion, and at once brought up a boy who was supposed to be one of the strongest, and made us fight. I must confess that we had no very good reasons for disliking one another, and that the fight was of a mild nature. But they had a way of putting you on your mettle. A stalk of straw was laid on one boy’s shoulder, and the other was told: ‘I bet you dare not knock that straw off!’ and for fear of being thought a coward you knocked it off. The other boy naturally would not submit to such an insult, and the fight began in good earnest. The big boys excited the one whose side they had taken, and the combatants were not parted until one of the two was victorious. The straw was tried in my case. I was the strongest, and covered myself with glory. My partisans were exceedingly proud of me, and said: ‘Millet is only six and a half, and he has thrashed a boy of more than seven years old!’