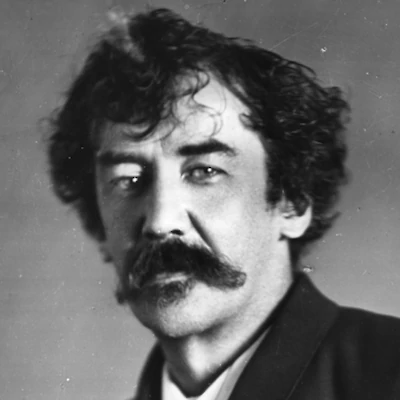

James McNeill Whistler

A lesson in making enemies

1834 – 1903[Editor’s note: we don't have much context for this writing, beyond that it was included in James Whistler’s collection of critical reviews and rebuttals “The Gentle Art of Making Enemies” and that it was first published in The World, May 22, 1878. We do see Whistler’s facination with music, and the impact it had on his work.]

Why should not I call my works “symphonies,” “arrangements,” “harmonies,” and “nocturnes"? I know that many good people think my nomenclature funny and myself “eccentric.” Yes, “eccentric” is the adjective they find for me.

The vast majority of English folk cannot and will not consider a picture as a picture, apart from any story which it may be supposed to tell.

My picture of a “Harmony in Grey and Gold” is an illustration of my meaning—a snow scene with a single black figure and a lighted tavern. I care nothing for the past, present, or future of the black figure, placed there because the black was wanted at that spot. All that I know is that my combination of grey and gold is the basis of the picture. Now this is precisely what my friends cannot grasp.

They say, “Why not call it ‘Trotty Veck,’ and sell it for a round harmony of golden guineas?"—naïvely acknowledging that, without baptism, there is no ... market!

But even commercially this stocking of your shop with the goods of another would be indecent—custom alone has made it dignified. Not even the popularity of Dickens should be invoked to lend an adventitious aid to art of another kind from his. I should hold it a vulgar and meretricious trick to excite people about Trotty Veck when, if they really could care for pictorial art at all, they would know that the picture should have its own merit, and not depend upon dramatic, or legendary, or local interest.

As music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of colour.

The great musicians knew this. Beethoven and the rest wrote music—simply music; symphony in this key, concerto or sonata in that.

On F or G they constructed celestial harmonies—as harmonies—as combinations, evolved from the chords of F or G and their minor correlatives.

This is pure music as distinguished from airs—commonplace and vulgar in themselves, but interesting from their associations, as, for instance, “Yankee Doodle,” or “Partant pour la Syrie.”

Art should be independent of all clap-trap—should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. All these have no kind of concern with it; and that is why I insist on calling my works “arrangements” and “harmonies.”

Take the picture of my mother, exhibited at the Royal Academy as an “Arrangement in Grey and Black.” Now that is what it is. To me it is interesting as a picture of my mother; but what can or ought the public to care about the identity of the portrait?

The imitator is a poor kind of creature. If the man who paints only the tree, or flower, or other surface he sees before him were an artist, the king of artists would be the photographer. It is for the artist to do something beyond this: in portrait painting to put on canvas something more than the face the model wears for that one day; to paint the man, in short, as well as his features; in arrangement of colours to treat a flower as his key, not as his model.

This is now understood indifferently well—at least by dressmakers. In every costume you see attention is paid to the key-note of colour which runs through the composition, as the chant of the Anabaptists through the Prophète, or the Huguenots’ hymn in the opera of that name.