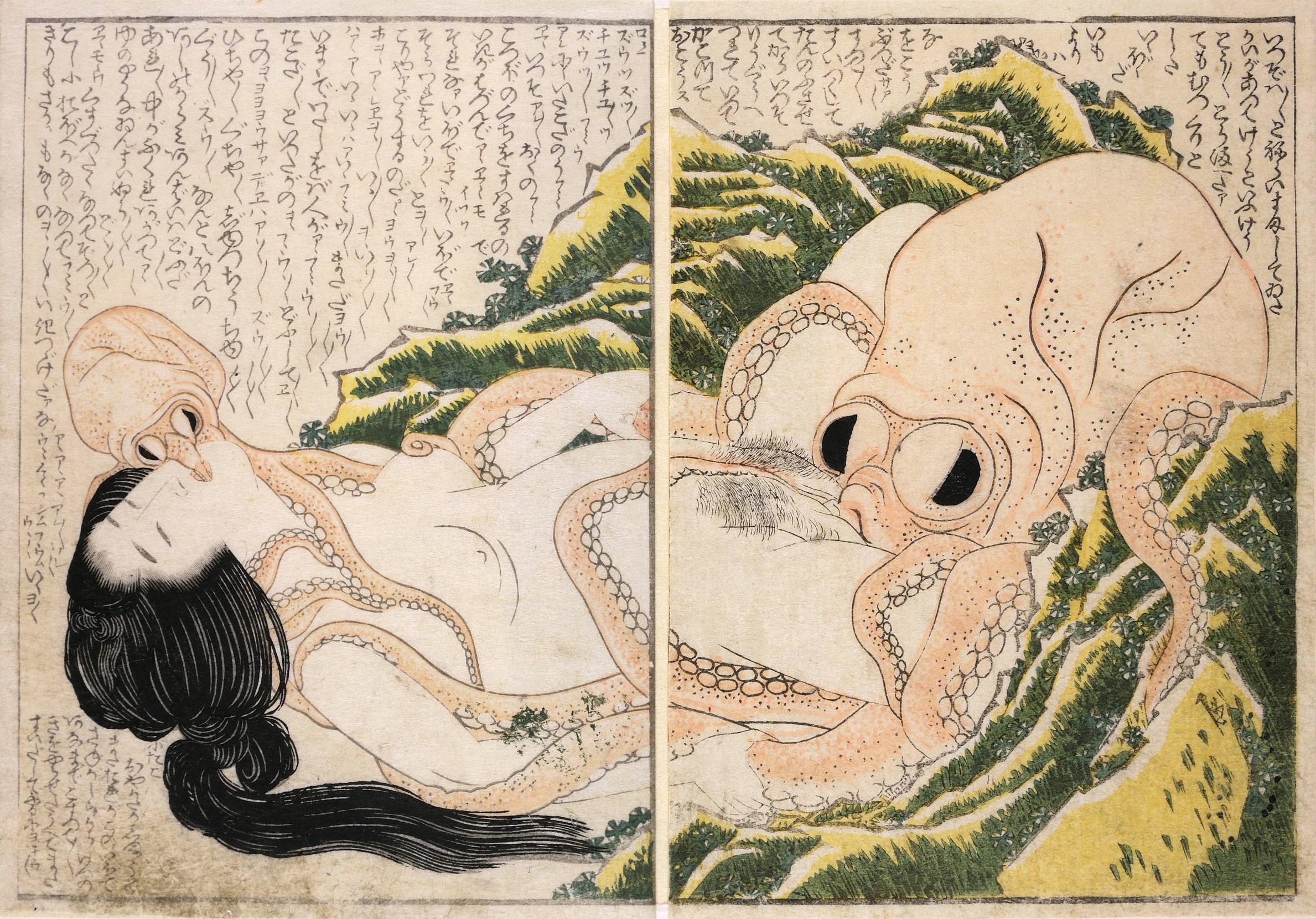

To fans of Katsushika Hokusai’s Great Wave, it might be a surprise to discover that the artist behind history’s most famous seascape also created of one of history’s most infamous and influential pieces of erotic art. Known in English as The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, and in the original, simpler, Japanese as 蛸と海女 (Tako no ama), or Octopus and Shell Diver, this small ukiyo-e woodblock print features a naked woman reclined across the seaweed-slick rocks of a coastal pool. Her eyes are closed, her face serene, her back is arched in pleasure. She is in the grip of a large octopus, whose mouth is fastened over her genitals. The octopus wears an expression I can only describe as determined. Its tentacles wrap the woman’s legs and support her back, and a second, smaller octopus plants a kiss on the woman’s mouth, an errant tentacle looped around her nipple.

It is, to put it lightly, an arresting image. At once graceful, with Hokusai’s masterful line work at its most expressive and the subtle pink and green coloring giving depth and vitality to the image—while also being, to a degree I assume varies considerably by the viewer, repulsive, transgressive, and exciting.

Once the shock of the image wears off to a degree, you may notice columns of Japanese text running behind the diver and her new friends. In a fluke of 19th century cultural exchange, it appears this rather extensive caption was left untranslated upon the print’s first arrival in the West, leaving curious viewers to speculate on the image’s intentions.

The French writer and critic Edmond de Goncourt proposed a metaphorical interpretation: a depiction of the pleasure and horror of death itself. Goncourt saw the figure as “lifeless, like a corpse” and the cephalopods as spiritual aggressors, a more violent interpretation than Hokusai intended (as we’ll soon see) but one that didn’t diminish Goncourt’s appreciation of the work. His personal copy of the print is inscribed “An admirable erotic book by Hokusai with prints of a harmony, a sweetness, a tenderness such has never been seen in France until now”—he’s still talking about psychospiritual death btw.

Today we have access to a translation thanks to James Heaton and Toyoshima Mizuho. Heaton translated the work in the early 90s for a special Eros themed issue of Kyoto Journal (Erotic Expression in Shunga‘, Kyoto Journal 18, 1991), and remains bemused that of all his many writings this translation has proliferated across the internet, all the way to Wikipedia, where I found it.

Far from the existential drama proposed by early Western viewers, the translated caption plants the image firmly in the realm of pornographic camp, full of lewd puns, feisty dialog, and onomatopoeic moans that Heaton describes as untranslatable. I present the translation here, and I dare you to avoid blushing while reading:

LARGE OCTOPUS: “My wish comes true at last, this day of days; finally I have you in my grasp! Your “bobo” is ripe and full, how wonderful! Superior to all others! To suck and suck and suck some more. After we do it masterfully, I’ll guide you to the Dragon Palace of the Sea God and envelop you. “Zuu sufu sufu chyu chyu chyu tsu zuu fufufuuu…”

MAIDEN: “You hateful octopus! Your sucking at the mouth of my womb makes me gasp for breath! Aah! yes… it’s…there!!! With the sucker, the sucker!! Inside, squiggle, squiggle, oooh! Oooh, good, oooh good! There, there! Theeeeere! Goood! Whew! Aah! Good, good, aaaaaaaaaah! Not yet! Until now it was I that men called an octopus! An octopus! Ooh! Whew! How are you able…!? Ooh! “yoyoyooh, saa… hicha hicha gucha gucha, yuchyuu chyu guzu guzu suu suuu….”

LARGE OCTOPUS: “All eight limbs to intertwine with!! How do you like it this way? Ah, look! The inside has swollen, moistened by the warm waters of lust. “Nura nura doku doku doku…”

MAIDEN: “Yes, it tingles now; soon there will be no sensation at all left in my hips. Ooooooh! Boundaries and borders gone! I’ve vanished….!!!!!!”

SMALL OCTOPUS: “After daddy finishes, I too want to rub and rub my suckers at the ridge of your furry place until you disappear and then I’ll suck some more. “chyu chyu..”

Yikes. Did you make it through? Mop your brow, loosen your collar, and we’ll get back into the history. The translation reveals, other than the obvious, that the scene is a reference or parody of sorts. Similar to contemporary pornography’s penchant for adult interpretations of popular franchises, Hokusai was referencing the popular Edo legend of Princess Tamatori, a humble shell diver who marries a member of the imperial court, then uses her diving skills to retrieve an heirloom pearl stolen by the sea dragon Ryūjin. Tamatori dives to Ryūjin’s undersea palace of Ryūgū-jō, pursued by an army of sea creatures, including octopuses. While Tamatori meets a tragic end, Hokusai’s version of the finale is altogether more titillating.

And Hokusai was not the first to delve into cephalopod lust. 30 years earlier Kitao Shigemasa depicted an erotic tryst between Tamatori and some octopi in his erotic book Yokyoku iro bangumi (Program of Erotic Noh Plays) from 1781, and Katsukawa Shuncho, a classmate of Hokusai’s in the Katsukawa school, drew a diver’s intercourse with an octopus in Ehon chiyo-dameshi (Erotic Book: Lusts of Many Women on One Thousand Nights) in 1786. Previous artists Suzuki Harunobu and Katsukawa Shunsho also toyed with the theme, though they lacked the confidence (or monetary motivation) to take their work to the explicit heights of later artists.

The “fisherman’s wife” was not Hokusai’s only foray into the erotic, not by a long shot. If fact, the print was part of volume 2 of a three-part series of erotic prints titled Kinoe no Komatsu or Pine Seedlings, each featuring nine scenes of women participating enthusiastically in their own pleasure. And Hokusai had many similar books of erotica, or enpon, under his belt by 1814, since the production of shunga erotica was bread and butter for nearly every Japanese artist of the day. A shunga commission could provide six months of livable income—good money for an itinerant artist like Hokusai.

Shunga translates to “spring pictures” and like the western association of renewal, bunnies, and blooming flowers to fertility, in edo Japan spring was a euphemism for sex. Shunga dates to at least Japan’s Heian period (794 to 1185), when painted handscrolls were passed between courtiers illustrating scandalous affairs within the imperial court—a sort of extra-explicit gossip rag. Popularized with the development of woodblock printing, which allowed easy reproduction at scale, shunga avoided several attempted bans and cultural reforms, proving too popular among all social groups and too lucrative to be shut down.

Western audiences were introduced to shunga during the increased trade with Japan during the late Edo and early Meiji eras, and the overt eroticism triggered exactly the pearl-clutching you’d expect. Frances Hall, the primary book dealer from Japan to the United States in the late 19th century, called shunga “vile books” though he admitted they were “executed in the best style [of] Japanese art.” Piles of shunga were acquired by the British Museum, but not displayed or cataloged (until relatively recently).

On its arrival in the west, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife made quite the impression on the art community. Félicien Rops, Auguste Rodin, Louis Aucoc, and Fernand Khnopff all created works inspired by the interspecies entanglement, and even Picasso drew his own significantly cruder and more upsetting variation in 1903, and in 1932 he painted a series of reclining nudes where the women seem to have become part octopus, capable of fearsome onanistic pleasure. The original print even appears in the TV series Mad Men as a metaphor for male domination. We can't avoid a jealous fascination with Hokusai’s octopus.

Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife is often linked to a subgenre of contemporary Japanese pornography where tentacled monstrosities violate women (and occasionally men) in scenes that intentionally abrogate decency. If you know you know—and if you don’t, consider carefully before Googling. But a counterpoint is proposed by Jerry S. Piven, a scholar whose dedicated most of his career to an academic evaluation of the darker sides of human nature, who claims that Hokusai’s light hearted erotica is less to blame for the more violent aspects of the modern genre than the collective trauma resulting from the World War Two.

Western audiences not only mistitled, but misunderstood Hokusai’s artwork. Calling the work The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife frames the scene as a fantasy or nightmare, distancing it from sticky reality. Introducing its protagonist by her relation to a theoretical offscreen husband sets her up to be either a damsel in distress, or a cheating spouse. Writer and artist Alistair Gentry offers a more gounded take, describing our blissed-out diver as a working professional embroiled in “the kind of a work-related fling that happens when your colleagues are mainly mollusks.” Tako no ama is a uniquely provocative artwork, that despite the taboo nature of the subject matter and cultural resistance to depictions of pleasure, has lived just as long, and has had arguably just as much influence as any great wave.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.